Born in Munich in 1860, Walter Sickert travelled all over Europe following his pictorial affinities before his death 82 years later. He began his career in the American painter James Whistler’s studio in London, before moving to France where he met the artistic avant-garde of the late 19th century, including Edgar Degas, Gustave Courbet, and Edouard Manet among others. From the latter, he kept the frank and realistic line and took the opposite view from the English painters at that time by representing popular leisure places or prostitutes.

Those three artists would eventually fuel the suspicion that the painter was indeed Jack the Ripper. In 1888, when Walter Sickert was 28 years old, the notorious serial killer was sticking in the working-class district of Whitechapel in London, where he mainly targeted easy preys, slitting their throats, and slashing their stomachs before leaving their bloody corpses in the street or on their own beds.

They may have shared the same flat... and same DNA

In 1907, British art lovers were stunned to discover Jack the Ripper's Bedroom – a dark canvas picturing a black silhouette dimly lit by a few rays of light filtering through the shutters. The painting, whose title and color palette are enough to give you goosebumps, was signed by Walter Sickert. The artist would have drawn his inspiration from his own bedroom. In the early 1900s, he moved to the working-class district of Camden Town in London, where he found his favorite subjects, starting with the many crimes that occurred there. Among these crimes is the murder of a certain Emily Dimmock, a prostitute whose throat was found slit from one ear to the other a few blocks away from his studio.

The case resurrected memories of Jack the Ripper throughout the British capital and inspired the artist to create this painting in and from his own bedroom in Camden. Y et, according to the rumors spread by the caretaker of his building, that room also belonged to the infamous serial killer who struck twenty years earlier... The reason for her suspicions? The restless behavior of the previous tenant at the time of the murders in 1888, whose unexpected departure perfectly coincides with the end of the murders. The room, the painter, the recent gruesome murder of Emily Dimmock... it didn’t take more than that for the gossips and fantasies to be fueled.

A century later, this theory has been confirmed by the American novelist Patricia Cornwell in two books published in 2002 and 2017. After an investigation that costed the author several million dollars according to her, the comparative analysis of Walter Sickert’s paintings and Jack the Ripper’s handwritten letters revealed a match in their DNA. It also allowed this criminology-loving author to discover that, in addition to their DNA or their flat, the two men also shared the same stationery and the same nickname “Nemo” ...

His nude paintings terrified England

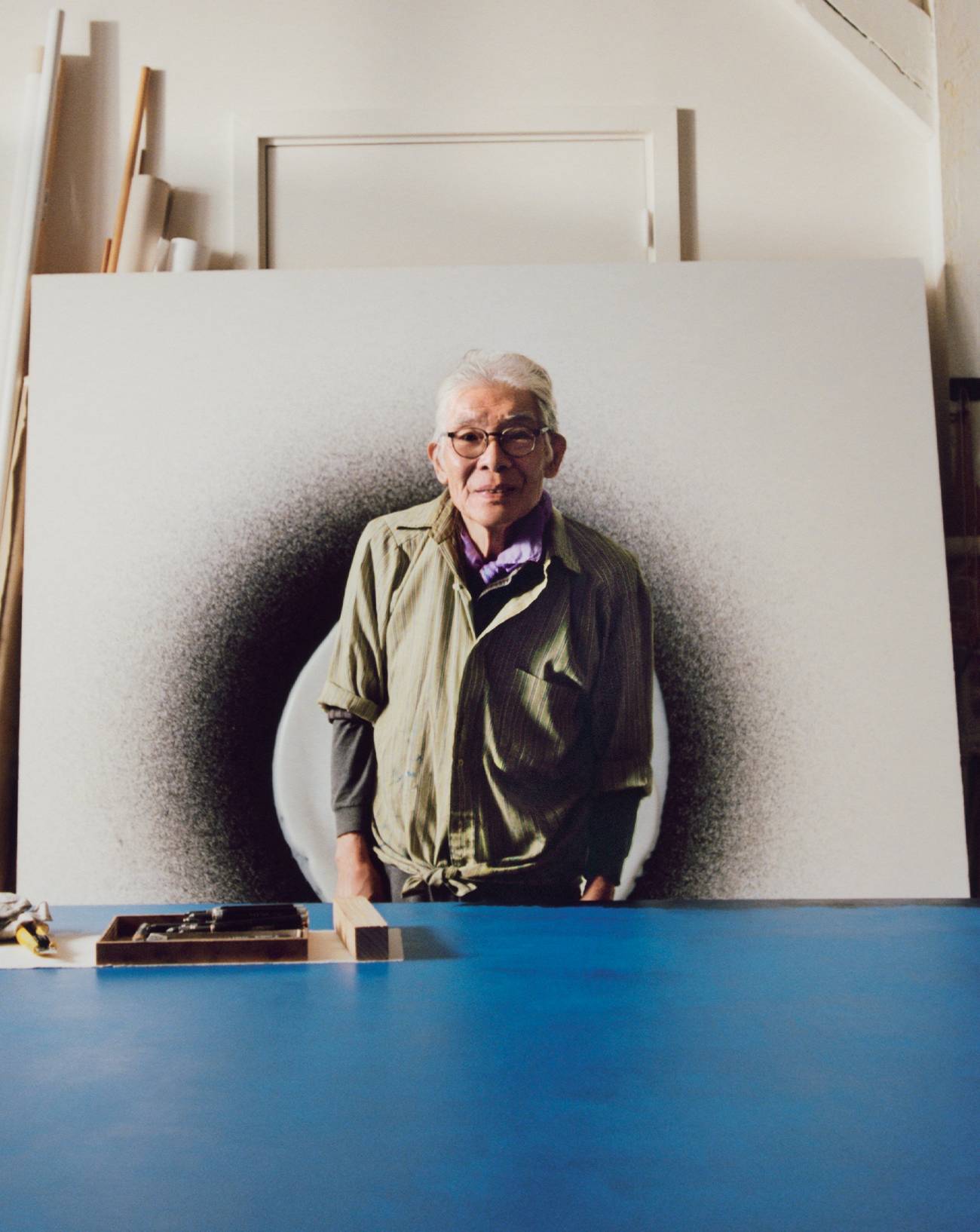

With their French and Italian influences, Walter Sickert’s paintings stand out among those of his British contemporaries. As the leader of the Camden Town Group in the early 1900s – a group of painters inspired by the London area and who lived there – he defended an aesthetic that staged ordinary people and everyday scenes with realistic tones and strokes. Thus, at a time when painting was struggling to break free from the classical and academic shackles in England, Sickert’s paintings used to shock the viewers.

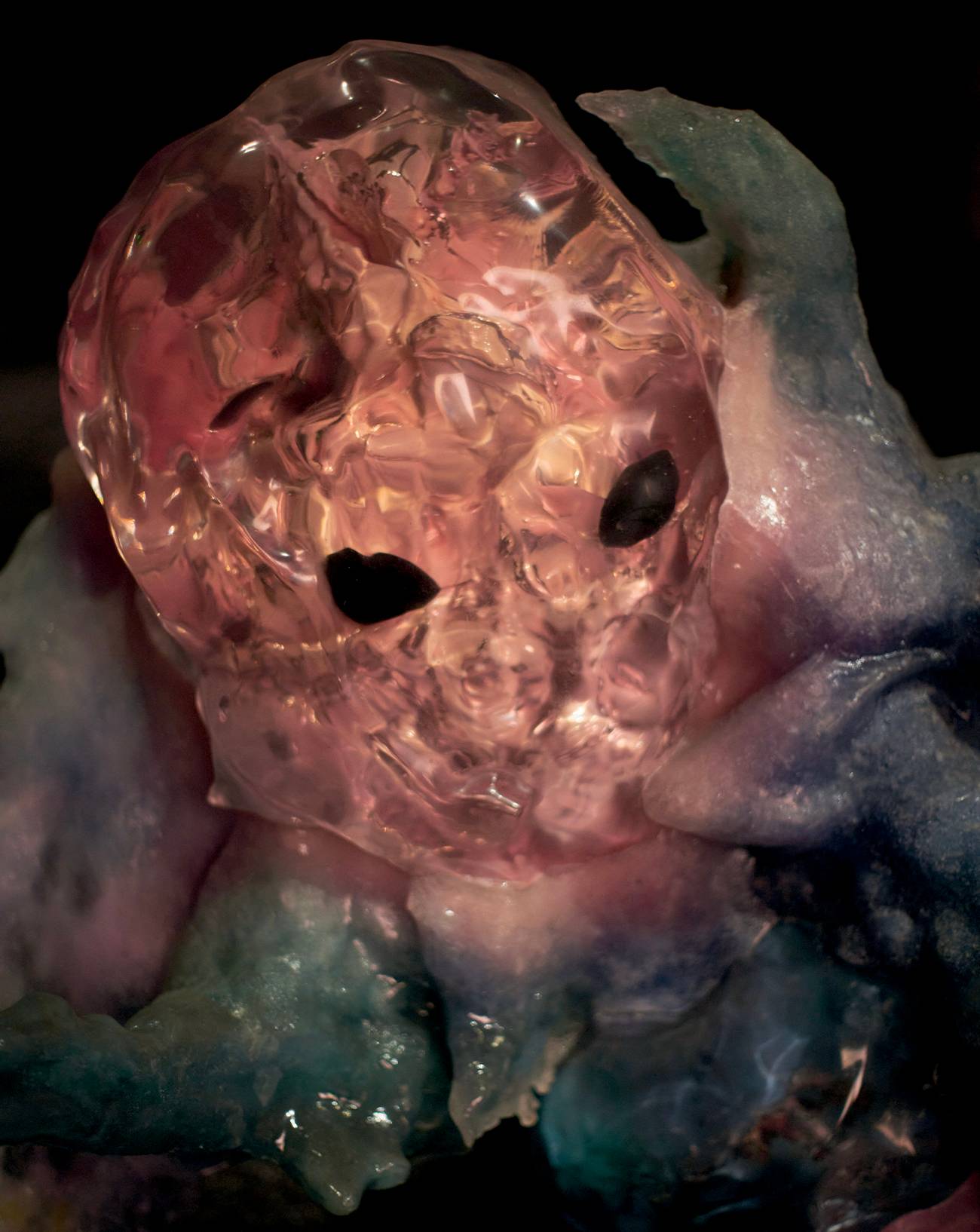

Leaving his brushstrokes visible on the canvas, he did not hesitate to depict with dull colors the drunken audience of music halls or naked prostitutes in bed, like his series The Camden Town Nudes, in which he included the painting The Camden Town Murder, directly inspired by the murder of Emily Crook. Immersed in dark atmospheres, deprived of any eroticism, his nudes are raw, and his models seem almost dead – so much so that the black lines delimiting the limbs are even compared to cuts... In each one of the paintings from this series, the faces fade away while the close- up angle associated with the strong brushstrokes accentuate the violence of the scenes.

His morbid fascination had often been criticized and the painter courageously defended it during a lecture at the Thanet School of Art in 1934. His shattering statement on the platform that “murder is as good a subject as any other” would eventually be a godsend to budding detectives and further fueled suspicion of his guilt.

The perfect culprit?

Were the naked women in Sickert’s paintings dead? Or worse, did he kill them himself? Raised by his paintings and his passion for crime stories, these suspicions have survived the painter’s death in 1942. His work remains unfamiliar to this day, except for his alleged links with the notorious serial killer of the late 19th century. While he was the object of a few accusations during his lifetime, his death unleashed a series of publications that directly implicated him in those crimes. In Jack the Ripper: The Final Solution published in 1976,

Stephen Knight portrayed him as an accomplice to the murders. In Jean Overton Fuller’s 1990 publication Sickert and the Ripper Crimes, he is the actual murderer. And while these publications are mostly fiction, the two subsequent books by Patricia Cornwell claim to have hard evidence, supported by DNA tests and calligraphic comparisons, which have since been refuted by specialists of the case. Firstly, Sickert was living in Dieppe, France, when the murders took place in 1888. Secondly, the several hundred letters signed by the murderer and sent to the police and newspapers at the time may mostly be hoaxes. Finally, and most importantly, the DNA screening carried out by Patricia Cornwell could, according to many scientists, be as much a match for the painter as for more than 400,000 people...

A gray area that keeps intriguing the lovers of the mystery surrounding Jack the Ripper’s murders, for which nearly 200 people are still suspected. Although he has never been questioned by Scotland Yard agents, Walter Sickert remains one of them. The themes and the titles of his paintings firmly place him in the foggy and dangerous London of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, to the point of making him an ideal suspect. To make up your own mind, go to the Petit Palais where some of the works from The Camden Town Nudes series are exhibited until January 2023 for the artist’s first French retrospective.