7

7

Why is Daniel Buren still relevant today? Bernard Blistène answers us

A legend in the world of contemporary art, with a career that spans six decades, Daniel Buren has lost nothing of his panache. Proof can be found at Reiffers Initiatives, where, during Art Basel Paris, he unveiled a new permanent intervention featuring his famous stripes on the building’s façade as well as a reworking of its glass ceiling. For Numéro art, the former director of the Musée national d’Art moderne at the Centre Pompidou, Bernard Blistène, reflects on the relevance of his work, now more topical than ever.

By Bernard Blistène.

Numéro art 17 is available at newsstands and on iPad since October 18th, 2025.

Daniel Buren, the giant of contemporary art

Nowadays, figuration is thriving. Not that it ever went away. And it has been aeons since a binary approach to painting stood up to scrutiny, something continually demonstrated by the many works which show that the subject of painting is painting itself. Figuration is back, and with it petty quarrels about subject, representation, expressiveness, and even illustration. In another era – for time passes, as I well know – a famous art historian and museum curator published Considération sur l’État des Beaux-Arts (Considerations on the State of the Fine Arts) [Jean Clair, Gallimard, 1983]. Tinged with a certain melancholy, the book was a success and became something of a bible. Its subtitle was Critique of Modernity.

Four decades later, its observations have not swayed Buren. It seems more likely that they both afflicted him and convinced him that the path he has been pursuing since the mid-1960s is the right one, and that the foundations on which he has built his artistic programme remain, at the very least, effective. Concepts such as in situ, site-specific work, visual tools, points of view, and the many others he has constantly developed now form a lexicon in which questions of space and architecture, and of light and colour, solicit the viewer through the numerous pieces – some permanent, but many temporary – that Buren continues to create around the world.

One of the most prolific artists of his time

Ever more inventive, Buren is no doubt one of the most prolific artists of his times. In 2021, he made a film that surveys, precisely and methodically, the entirety of his work from the 1960s to today. Intended to be updated over time, À contre-temps, à perte de vue is both a lesson in filmmaking and a perfect example of what the analysis of an approach can be. Both personal and didactic, it examines an output in which aesthetics and politics are inseparable.

With all due respect to the many authors who have written about Buren, it is clear that he has long understood, as evidenced by his often captivating Écrits, that no one does it better than him. As I pen lines that pay yet another tribute to an oeuvre I have never ceased to admire, I’m trying hard to bear that in mind.

Rethinking the dynamics between the artwork and the viewer

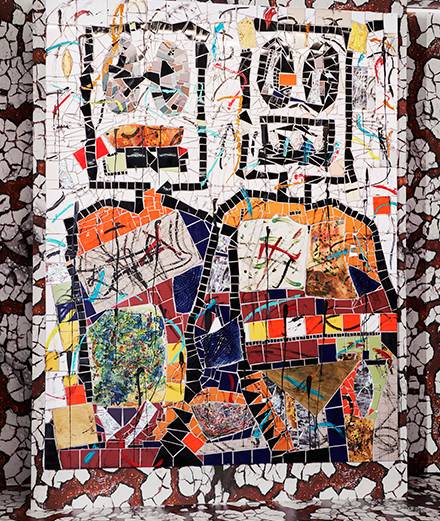

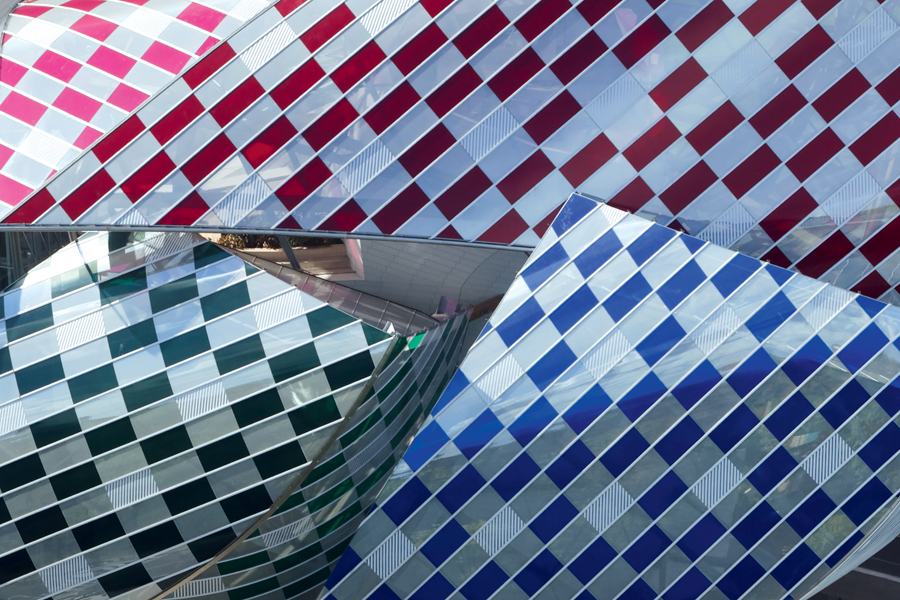

These days, Buren is busier than ever. His installations proliferate in both public and private settings, in response to the commissions he receives. As analyses of his work, the articles and monographs about Buren make clear the acuity and inventiveness of his proposals as he experiments with new materials, combining glass and Plexiglas, or LEDs with the most cutting-edge techniques.

As Loran Stosskopf already noted back in 1991, “Neither painting, sculpture, architecture, or decoration, each of Buren’s realizations renews the relationship between the work, the place, and the viewer.” The haters – for he still has some, and always will – denounce what they see as his incredible prolixity. To those who say he’s overdoing it, he responds by producing even more, devising mechanisms that never cease to surprise us and draw us irresistibly into his world.

So solid are the foundations on which he built his method, he can deploy ever more ambitious proposals without renouncing his initial conceptual framework. Though he never ceases to “deconstruct” the sites he transforms, he plays with colour and materials with constantly renewed virtuosity, his Daedalian devices leading him to develop an ever more complex and playful relationship to architecture. Since Buren has fun, so do we!

Historic works, from Palais-Royal to the Venice Art Biennale

Does this mean the work loses its analytical power? That the discourse on which it hinged has been forsaken? Has the notion of “institutional critique,” to which he himself greatly contributed before it was coopted by critical exegesis, become obsolete? Has Buren disavowed his own convictions in increasingly complex works that lead him to disrupt each of the spaces he engages with? “Disrupt,” or as others might say “upset” or “upend.” This playing with words is my way of emphasizing that, in an artistic context which delights in illustrating the world’s misfortunes, Buren’s work refuses commiseration, preferring instead the force of subversion to challenge traditional hierarchies and the established order.

Let us not forget Les Deux Plateaux (1986) in the courtyard of the Palais-Royal in Paris! Or his Golden Lion-winning Pavillon that same year at the Venice Art Biennale, which saw him dare to carve 8.7 cm stripes into the neoclassical walls of the French pavilion! Or the insolence of Le Musée qui n’existait pas (The Museum That Did Not Exist), a true defence of the Musée national d’Art moderne’s presence in the Centre Pompidou (2002)!

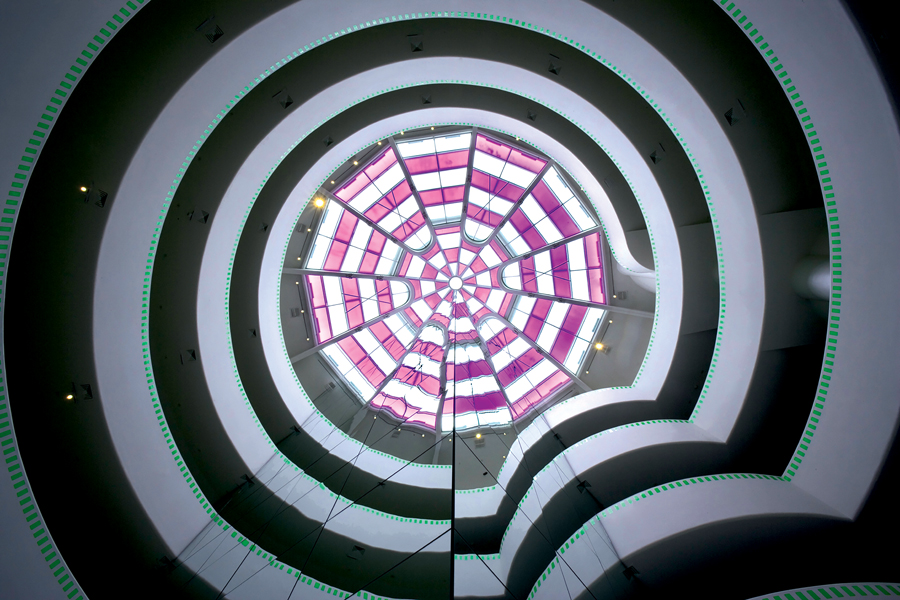

Or L’Observatoire de la lumière, a site-specific installation at Frank Gehry’s Fondation Louis Vuitton (2016)! Four examples, four French milestones among dozens of other projects that are just as ambitious: Buren, who is always ready to saddle up once more, sketching out his projects like “vanishing points” or axonometric drawings similar to the flows that, according to Deleuze and Guattari, “deterritorialize” us.

The art of location and of in situ

Behold the website listing all his works! Behold the absurd titles he gives them, as well as the Photos-Souvenirs he makes of each one, which preserve the memory of often ephemeral realizations. Behold all the places where Buren intervenes, “free of pounding beat, heavy or terse,” [Paul Verlaine, Art poétique from Jadis and Naguère (1885)] “where the indecisive joins the precise.”

Yes, there is no doubt a poetic art at the heart of Buren’s work, a poetic art but also an oeuvre in which “Nothing will have taken place but the place,” as Mallarmé postulated [Stéphane Mallarmé, A Throw of the Dice Will Never Abolish Chance (1897)], and which Guy Lelong references in one of the most subtle texts written to date about the artist. A way of reminding unhappy people that Modernism – and not modernity, whatever some pessimists may think – remains an unfinished project and that Buren is fully armed to prove it to us.

“Daniel Buren and Miles Greenberg.” 2025 Mentorship exhibition, from October 24th to December 13th, 2025, at Reiffers Initiatives, 30 rue des Acacias, Paris 17th.