3

3

Elmgreen & Dragset prennent d’assaut la place Vendôme : “L’humanité va-t-elle disparaître pour laisser place à la nature?”

Des étoiles de mer sur la place Vendôme, un sol éventré en plein Marais… Les responsables ? Elmgreen & Dragset, duo explosif parti à l’assaut de Paris. Numéro art les a rencontrés dans leur atelier de Berlin. Extrait de l'interview publiée dans le Numéro art #3.

Propos recueillis par Thibaut Wychowanok,

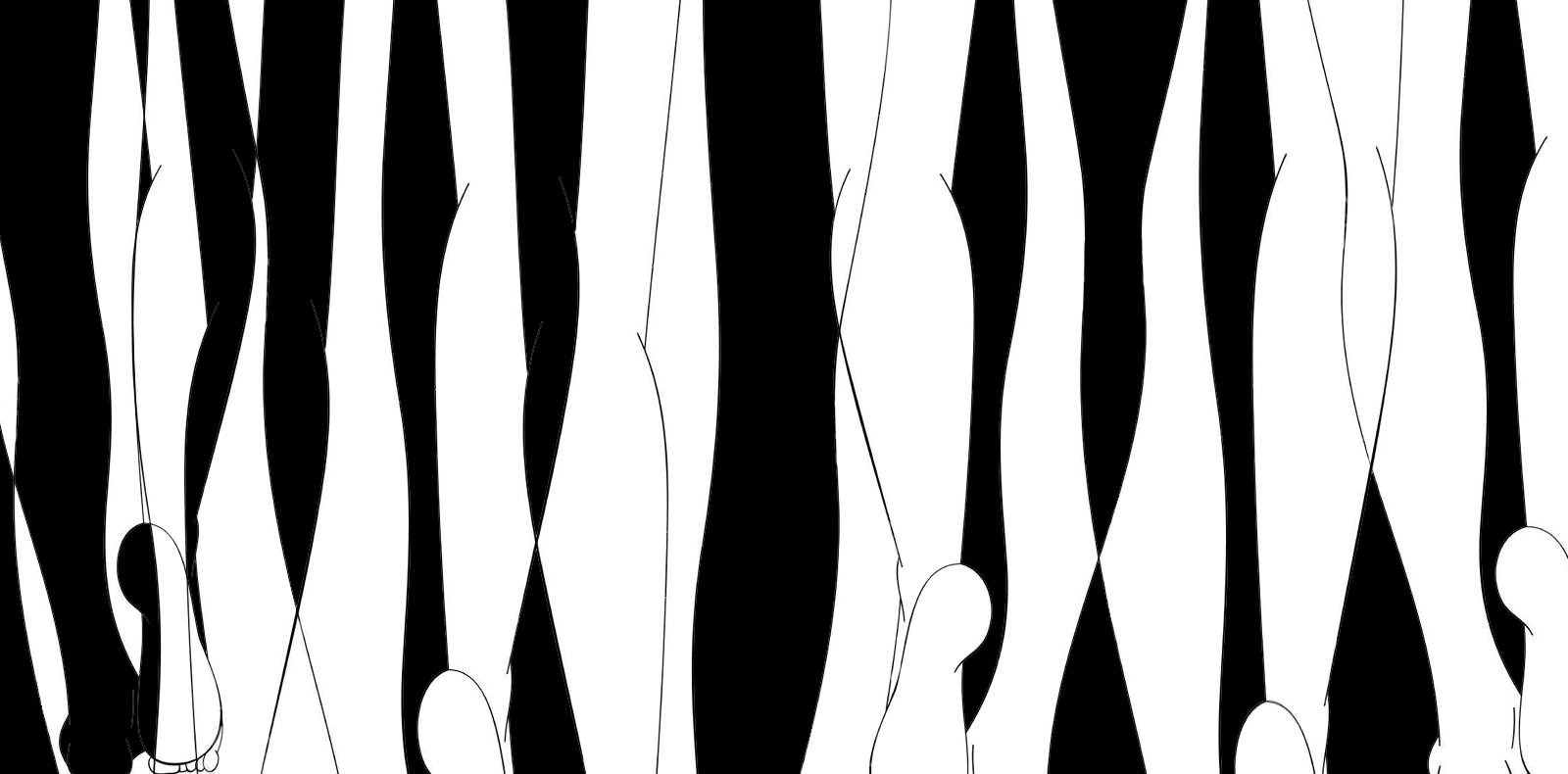

Portrait Miles Aldridge,

Réalisation Samuel François,

Interview by Thibaut Wychowanok,

Portraits Miles Aldridge,

Realisation Samuel François.

Publié le 3 septembre 2020. Modifié le 18 juin 2024.

Numéro art : Commençons par votre intervention à Paris, pendant la FIAC. Plus d’une centaine d’étoiles de mer – des sculptures taille réelle – ont pris d’assaut la place Vendôme. La nature reprend-elle ses droits ?

Michael Elmgreen : Nous voulions créer une image digne d’un film de science-fiction : la Seine a submergé la place et a laissé derrière elle des étoiles de mer. Ces créatures sont un peu comme des aliens, de sympathiques intrus. Dans les temps anciens, les étoiles de mer étaient d’ailleurs considérées comme le reflet au fond des mers des étoiles déployées dans le ciel. Ce sont aussi des créatures dotées d’un énorme instinct de survie. Vous pouvez les démembrer entièrement, elles renaîtront toujours à partir d’un bras. Elles symbolisent une forme de résilience de la nature.

L’œuvre sera par la suite installée au Domaine des Étangs, situé à Massignac, entre Limoges et Angoulême…

Ingar Dragset : En ville ou en pleine nature, au Domaine, l’œuvre se fait l’écho des grands enjeux environnementaux. Une catastrophe écologique, un raz-de-marée sont-ils à l’origine de la présence de ces étoiles ? L’humanité a-t-elle disparu pour laisser place à la nature ? Le choix originel de Paris n’est pas neutre. Nous avons assisté aux crues impressionnantes de la Seine ces dernières années. La ville a aussi accueilli la COP21 dont l’accord a finalement été rejeté par Trump.

“L’Église nous demande de souffrir et de nous sentir coupables, comme Jésus crucifié. Mais ici, le geste est une recherche de plaisir.”

Numéro art: Let’s start with your intervention in Paris during the FIAC. More than 100 star sh—life-size sculptures—took over the Place Vendôme. Has nature reclaimed its rights?

Michael Elmgreen: We wanted to create an image worthy of a science ction lm: the Seine ooded the square and left star sh in its wake. These creatures are a bit like aliens or gentle intruders. In ancient times, star sh were thought of as the underwater re ection of the stars in the skies. They also have an enormous survival instinct. You can cut off all of its arms and a star sh will grow them back.

Afterwards, the work was installed in the Domaine de l’Etang near Angoulême…

Ingar Dragset: Whether in the middle of the city or in the middle of nature at the Domaine, this work re ects larger environmental issues. Were the star sh brought here by an ecological catastrophe or a tidal wave? Did humanity disappear to let nature take over? The original choice of Paris was not neutral. We’ve witnessed the Seine ooding rsthand over the last few years. The city also welcomed the COP 21—which Trump refused to sign.

After Paul McCarthy’s giant dildo or Oscar Tuazon’s imposing structures, your place Vendôme intervention is almost minimalist.

M.E.: Everything in the Place Vendôme is impressive. Its monumentality and even its column are expressions of power. We wanted to counteract that with a horizontal, less macho work. Something more approachable that people can reach out and touch.

Power, and the way it’s symbolically incarnated in structures – especially architecture, hierarchies, and thought patterns –, has always been at the heart of your work. You’ve just opened a huge show at London’s Whitechapel Gallery that includes several of your iconic pieces.

M.E.: Whitechapel’s upper oor welcomes a kind of retrospective of our work. Our sculptures of the little boy fascinated by a weapon hanging on the wall and the other little boy crouched in a chimney are there. Most of our work questions toxic masculinity. As children, our education encourages certain behaviors. We expect little boys to play with toy guns and be fascinated by rearms. It isn’t said often enough that men are responsible for 99,9% of gun violence. It’s a masculine problem. And when the little boy doesn’t follow the expectations of his parents—of society—he suffers, feels guilty, and refuges himself in the chimney.

“The church asks us to suffer and feel guilty in the presence of the crucified Jesus, but here the act is voluntary.”

Après le sextoy géant de Paul McCarthy ou les imposantes structures d’Oscar Tuazon, la place Vendôme accueille avec vous une installation presque minimaliste.

Michael Elmgreen : Place Vendôme, tout est fait pour impressionner. La monumentalité de la place, sa colonne, sont des expressions du pouvoir. Nous voulions jouer en contrepoint, avec une œuvre horizontale, beaucoup moins machiste. Une œuvre qui se laisse approcher et toucher.

Le pouvoir, et la manière dont il s’incarne symboliquement dans des structures, des hiérarchies et des modes de pensée, ou plus concrètement dans des architectures, a toujours été au cœur de votre travail. Vous venez justement d’inaugurer une vaste exposition à la Whitechapel Gallery à Londres qui présente plusieurs de vos œuvres iconiques.

M.E. : L’étage de la Whitechapel Gallery accueille une sorte de rétrospective. On y trouve notre sculpture du garçonnet fasciné par une arme accrochée au mur, ou celle du petit enfant recroquevillé dans une cheminée. Il y est beaucoup question d’une masculinité que je qualifierais de toxique. Quand nous sommes enfants, notre éducation encourage certains comportements. On attend d’un garçon qu’il joue avec des armes, qu’il soit fasciné par les armes. Et on ne dit pas assez que les violences avec armes à feu sont le fait, à 99,9 %, des hommes. Ce problème est un problème masculin. Et lorsque le petit garçon ne répond pas aux attentes de ses parents – de la société – il souffre, il se sent coupable… et se réfugie dans la cheminée.

You’re also presenting a Christ on the cross, but the cruci ed man’s backside faces the public. It is close to a sado-maso scene.

M.E.: The church is another power structure. It asks us to suffer and feel guilty in the presence of the cruci ed Jesus, but here the act is voluntary. It’s made in the search for pleasure.

You’re also presenting a new installation that takes over the rst oor of Whitechapel. What is it?

I.D.: We transformed the ground oor into an abandoned public pool—like there are so many of in London. A plaque explains that a real-estate consortium planning to convert it into a private spa bought the property. The swimming pool is the symbol of the fate of so many public spaces: a privatization that participates in gentri cation. It’s a real epidemic in London. Low-income housing is being pushed out, while glass towers and luxury residential complexes— for people who almost never live there—are multiplying. When you walk through certain London neighborhoods at night there’s not one light on. The houses and apartments aren’t lived in. They’re nancial investments. The previous mayor Boris Johnson is responsible for this. He not only had a disastrous impact on the government and Brexit, but on the city. When we inaugurated our sculpture in Trafalgar Square, our greatest victory was to have Joanna Lumley from Absolutely Fabulous present the piece instead of him.

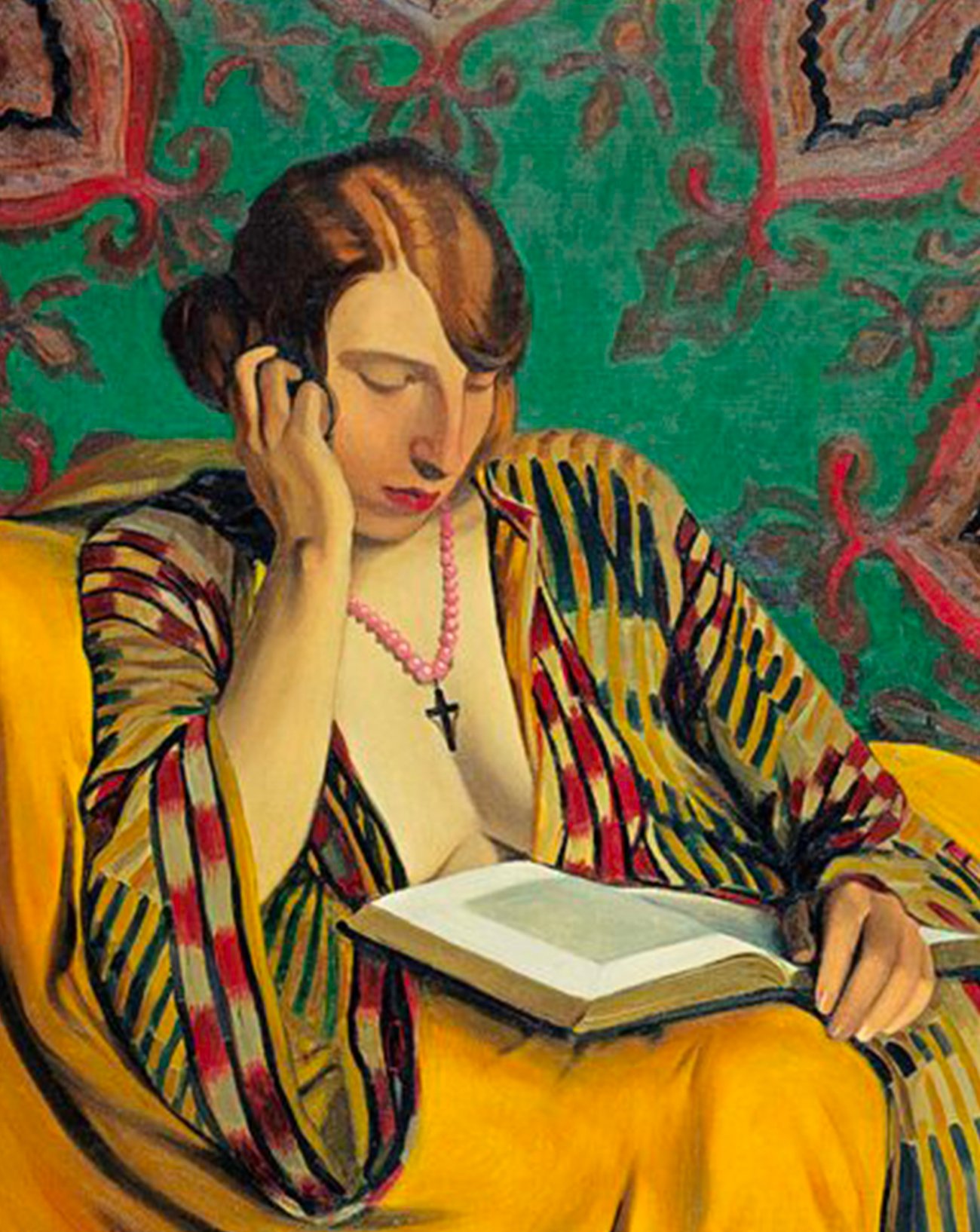

The Perrotin gallery also welcomes an important exhibition of your work this fall, including the installation you were photographed with for this magazine. What does this oor of exploded asphalt represent?

M.E.: We tried to create a mental image of the epoch we’re living in—an epoch where we don’t know where we’re going anymore. You know, this feeling of things dramatically changing in the bad way. The oor disappears beneath your feet and you don’t know what to do. All that we believed in, all that we took for granted—our way of voting, writing news, even our conception of truth— is being questioned. Today, how can we know whether any information is factual? We’re no longer able to live together or make communities. And Brexit is only one of many symptoms. We’re living in an atomized society. Individualism dominates; it’s the reign of survival. We no longer have communal experiences.

Vous présentez également un christ en croix, mais l’homme crucifié présente ses fesses au public. On est plus proche de la scène sadomaso.

M.E. : L’Église est une autre structure de pouvoir. Elle nous demande de souffrir et de nous sentir coupables, à l’image de Jésus crucifié, mais ici, le geste est volontaire. C’est une recherche de plaisir.

Vous présentez également une nouvelle installation au rez-de- chaussée de la Whitechapel. De quoi s’agit-il ?

I.D. : Nous avons transformé ce niveau en piscine publique abandonnée, comme on en trouve à Londres. Une plaque accrochée au mur explique comment ce lieu a été racheté par un consortium immobilier qui souhaite le reconvertir en spa privé. La piscine est le symbole du sort réservé à de nombreux espaces publics : une privatisation qui participe à la gentrification des villes. À Londres, c’est une véritable épidémie. Les petits revenus sont poussés vers la sortie et on multiplie la construction de tours en verre, de complexes résidentiels hors de prix pour des gens qui n’y vivent presque jamais. Lorsque vous vous baladez la nuit dans certains quartiers, presque aucune lumière n’est allumée. Les maisons et les appartements ne sont pas habités. Ce ne sont que des investissements financiers. L’ancien maire Boris Johnson est responsable de cet état de fait. Son action a eu un impact désastreux sur le gouvernement, mais aussi sur le Brexit et sur la ville. Quand nous avons inauguré l’œuvre Powerless Structures, sur Trafalgar Square, notre plus grande victoire a été de faire en sorte que Joanna Lumley, de la série Absolutely Fabulous,inaugure la pièce plutôt que lui.

[…]

RETROUVEZ L'INTÉGRALITÉ DE L'INTERVIEW DANS LE NUMÉRO ART #3, EN KIOSQUE ET SUR LE ESHOP NUMÉRO.

Is your interest in communal life linked to your Scandinavian origins? How can we make a community today?

I.D.: Post-war Europe built itself up from the idea of bettering the lives of the working classes and creating public infrastructures that would ensure peaceful coexistence. Keynes defended the welfare state…he was British.

M.E.: To respond to your second question, the problem today is that people no longer recognize themselves in their old identities. To be working class, gay, or Danish doesn’t mean the same thing today that it did 30 years ago. Identities are multiple. You take a bit from the right and the left… you’re more active in the construction of your identity today. Social media has greatly facilitated this phenomenon. But it has also decreased the urgency of coming together. In our community, an application like Grindr empties the bars. Why go out when you can talk to hundreds of boys from your couch? Meanwhile, the working class has transformed into a formless middle class and lost the force of its identity. An identity and pride that was at the origin of the punk movement. Our work has always been about the way identity is formed in a world where all the categories and de nitions are being reshuf ed.

Since the beginning, you’ve used the strategy of surprise. Your installations upset a certain reality, or normality, in a way that disarms the viewer. Beyond grabbing our attention, your work invites us to change the way we see and think.

I.D.: The effect of surprise is essential. Even truck drivers stopped short when we installed the Prada boutique reproduction along the desert highway in Marfa. But we want to show through our interventions that it’s possible to change things. It’s possible to stick hundreds of star sh on the oor of one of most beautiful historic squares in Paris, despite the constraints of patrimonial preservation. It’s possible to convince a classic London institution to reinvent its architecture from the ground up. It’s possible to act and think outside conventions. Social structures, power structures, and physical structures are malleable and modi able. People are often petri ed by fear. Art won’t revolutionize the world but it can help us to have less fear—less fear of change and the new, by showing how changing a classic institution or established order can have happy consequences. And the less people are afraid, the less they’ll be manipulated. It’s one of the objectives of our artistic practice.

This Is How We Bite Our Tongue, until January 13, 2019, Whitechapel Gallery, London.

Elmgreen & Dragset, from October 13 to December 22, Galerie Perrotin, Paris.