14

14

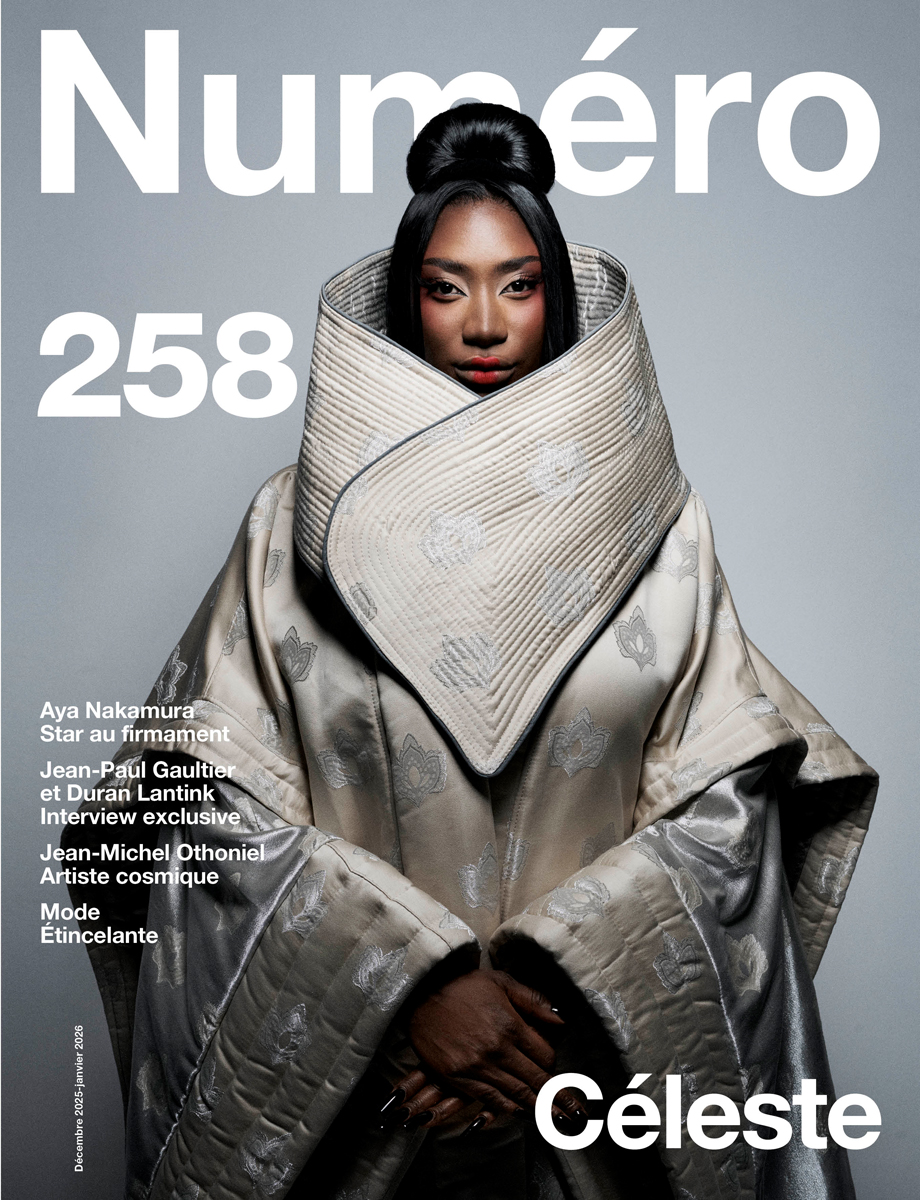

Fondation Louis Vuitton explores how Basquiat and Warhol’s collaboration became historical

En 1983, Jean-Michel Basquiat et Andy Warhol commencent à réaliser des œuvres en duo, inaugurant une production prolifique à quatre mains qui s’étalera sur deux ans. La Fondation Louis Vuitton présente jusqu’au 28 août l’étendue de cette collaboration exceptionnelle et ultra prolifique des deux Américains, qui a définitivement changé le cours de leur carrière et de leur pratique.

Par Matthieu Jacquet,

by Matthieu Jacquet.

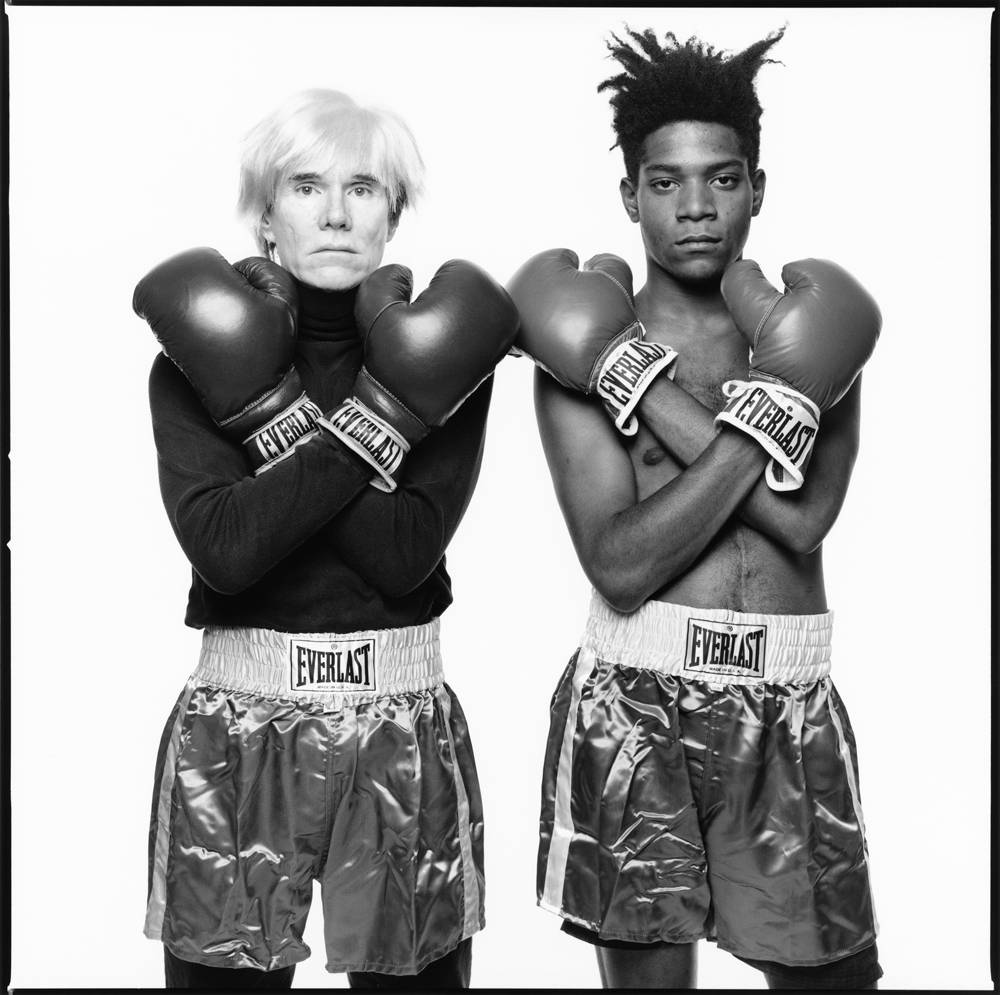

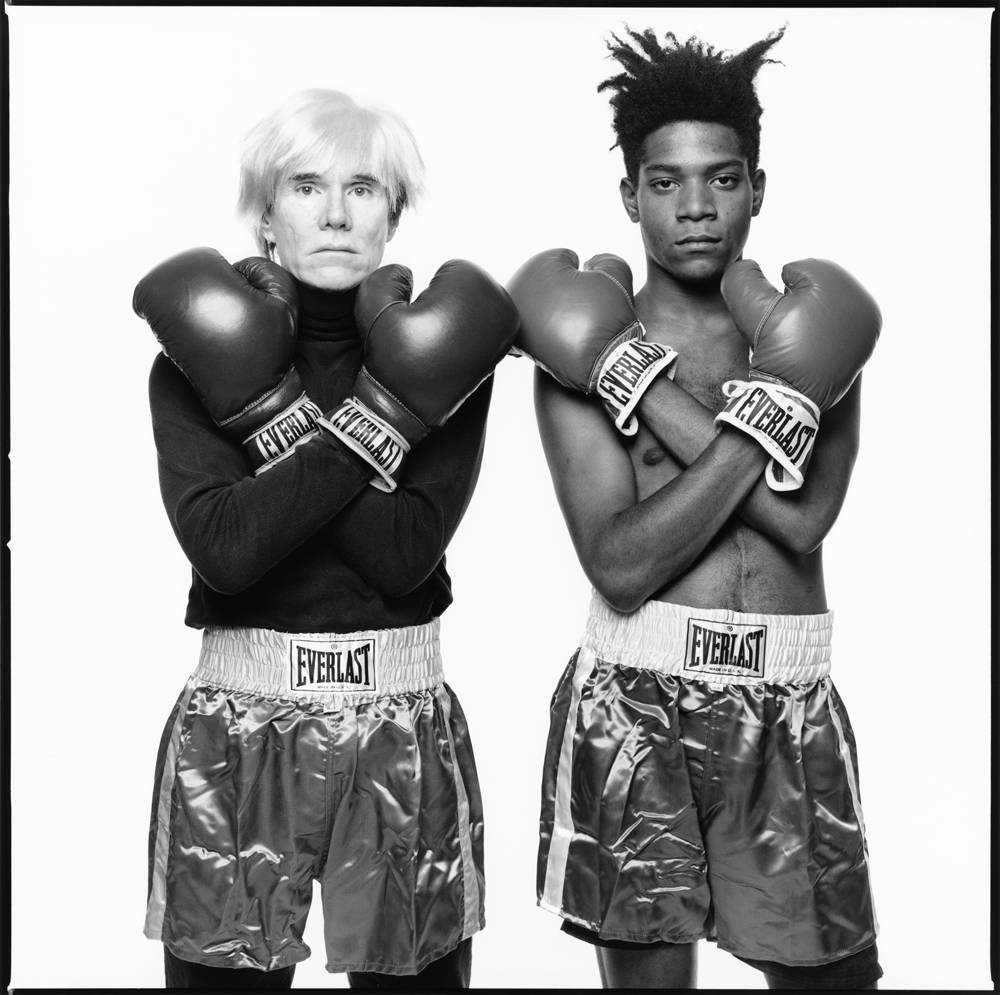

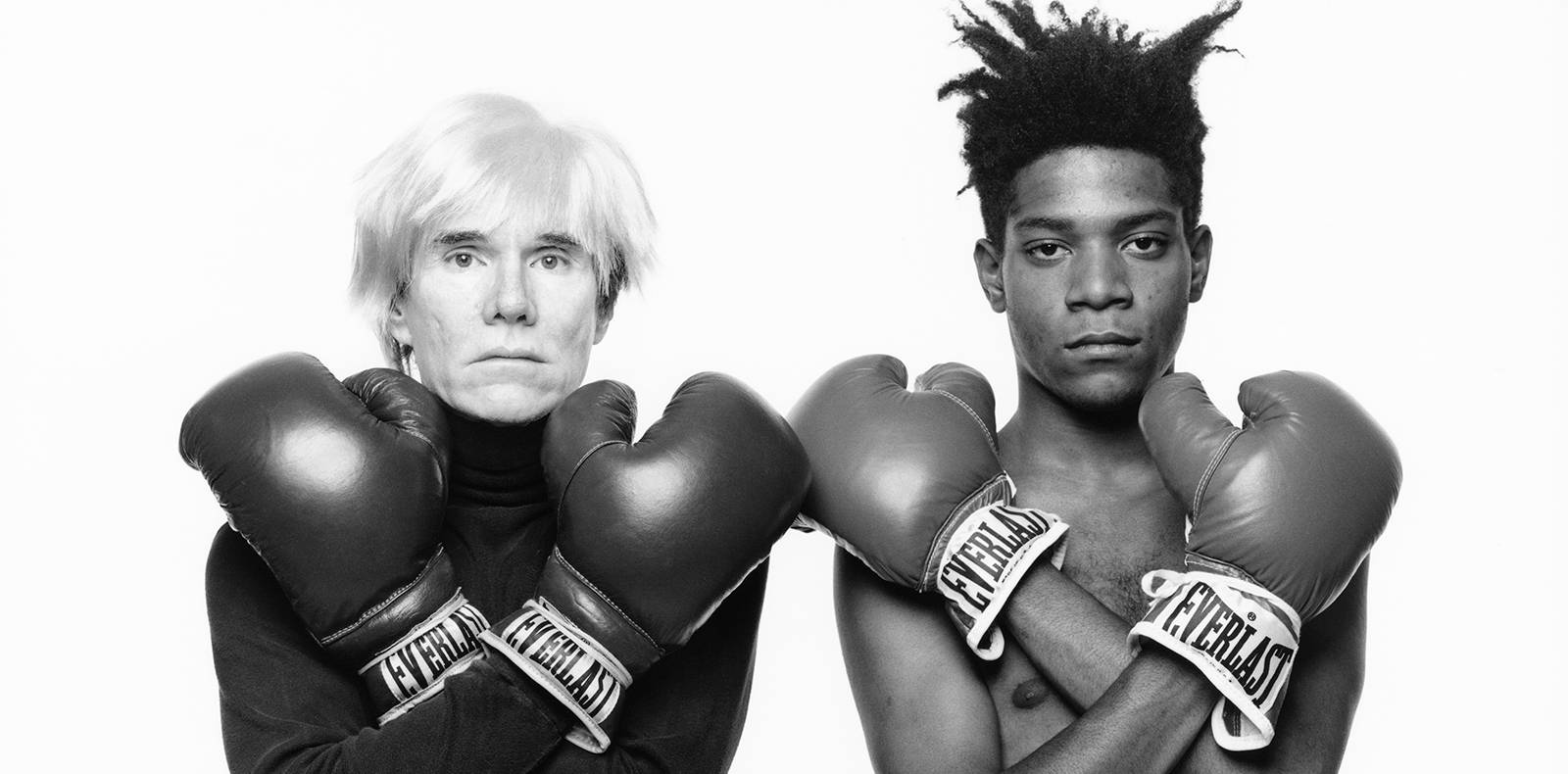

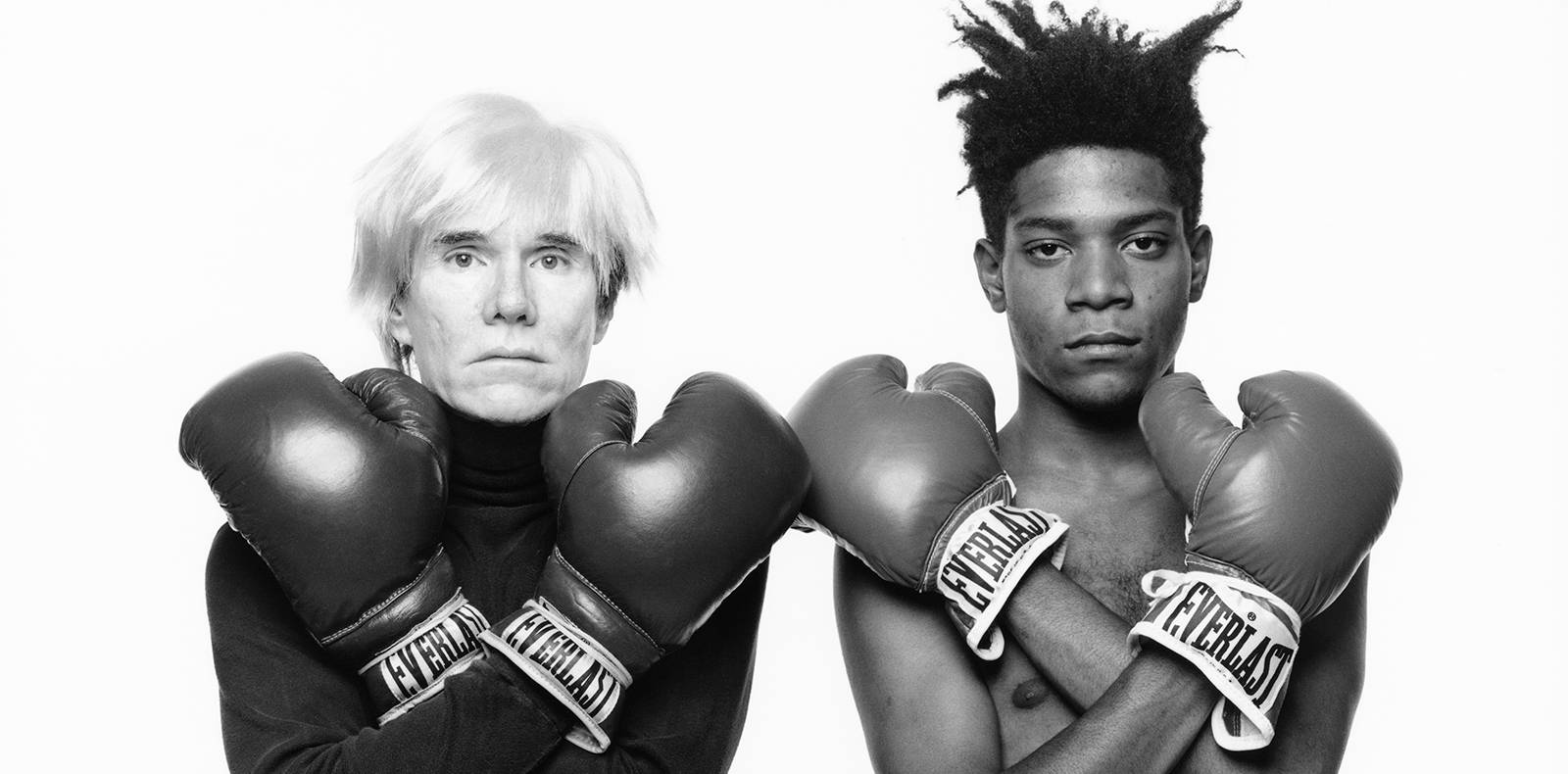

Debout côte-à-côte, les bras croisés et vêtus de gants et shorts de boxe de la marque Everlast, Andy Warhol et Jean-Michel Basquiat sont parés pour un match endiablé. Plutôt que s’affronter sur cette photographie de 1985, signée Michael Halsband, ces deux figures majeures du New York underground de la seconde moitié du 20e siècle font équipe face au spectateur. Une manière puissante d’introduire leur prolifique collaboration artistique entamée en 1983 : pendant deux ans, les deux artistes réaliseront une centaine d’œuvres “à quatre mains”, toiles souvent monumentales qui réunissent deux démarches et styles picturaux complémentaires. Jusqu’à la fin août, l’exposition “Basquiat x Warhol” à la Fondation Louis Vuitton se concentre sur cette rencontre prolifique à travers quelques 300 œuvres, montrant combien cet épisode a aussi bien marqué la carrière des deux artistes que l’histoire de l’art.

A la Fondation Louis Vuitton, une rencontre inattendue entre deux artistes majeurs

Andy Warhol (1928-1987) et Jean-Michel Basquiat (1960-1988) auraient pu ne jamais se rencontrer. Séparés par 32 années, les deux artistes proviennent de milieux totalement différents : originaire de Pittsburgh et diplômé des Beaux-arts, le premier fait dans les années 50 ses armes à New York dans la communication publicitaire et le design de chaussures. Élevé à Brooklyn dans les années 60 par une famille d’origine haïtienne, le second commence par investir la rue avec le graffiti et son fameux logo signature, SAMO. Si 1982 est souvent citée comme l’année de leur première rencontre, autour d’un déjeuner, celle-ci a en réalité lieu trois ans plus tôt. Âgé de seulement 17 ans, Jean-Michel Basquiat passe à l’époque ses journées à interpeler les passants de la ville pour leur vendre ses collages sur cartes postales. Un jour, dans un restaurant de Soho, il aperçoit Andy Warhol en compagnie de Henry Geldzahler, directeur du Metropolitan Museum of Art. Admiratif du premier, le jeune homme prend son courage à deux mains et les aborde pour leur proposer deux de ses œuvres, qu’ils paieront 1 dollar chacune. Bien que mémorable pour Basquiat, ce moment ne le sera pas tant pour Warhol, qui restera les années suivantes assez dubitatif sur le potentiel du New-Yorkais.

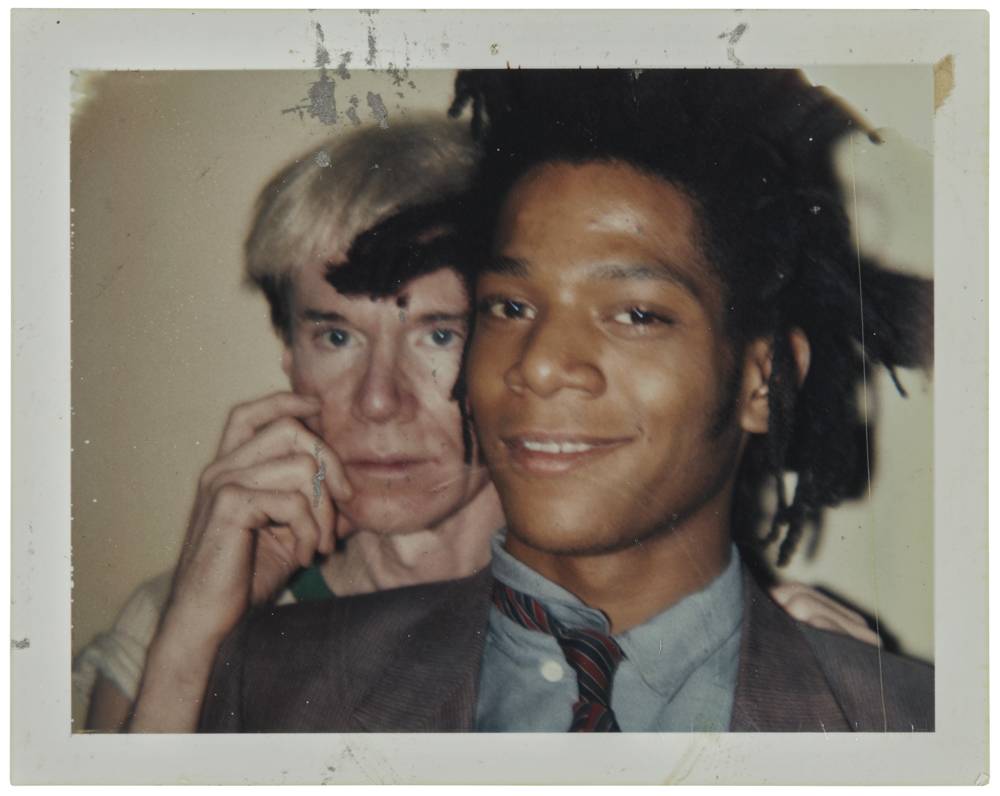

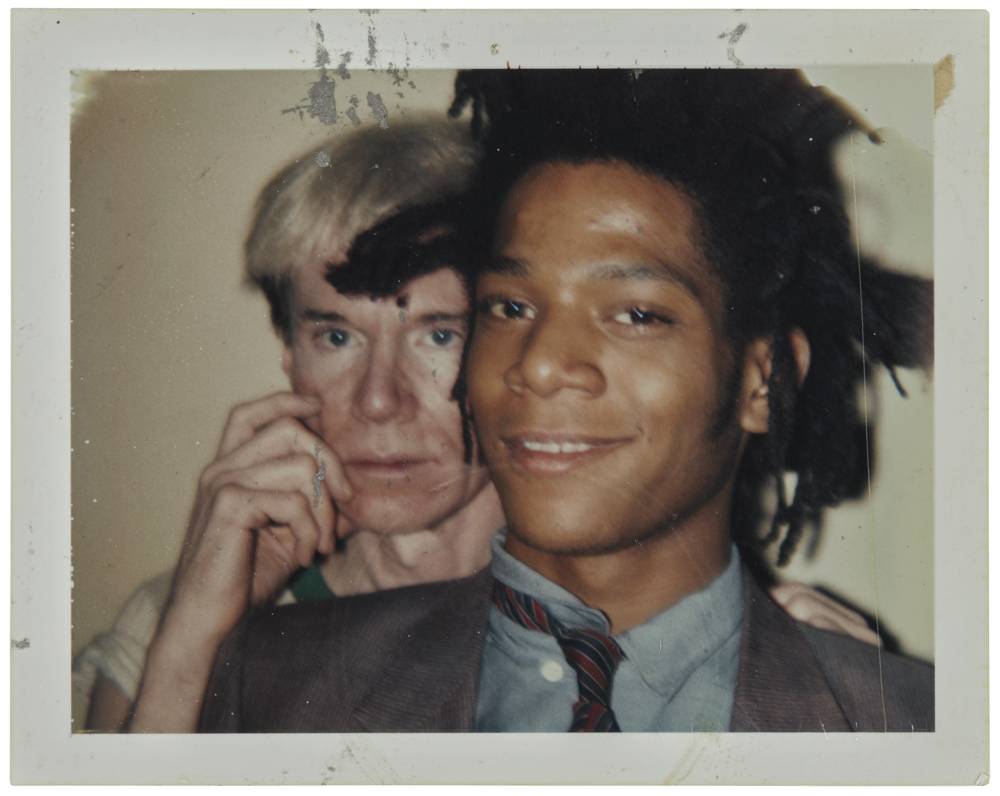

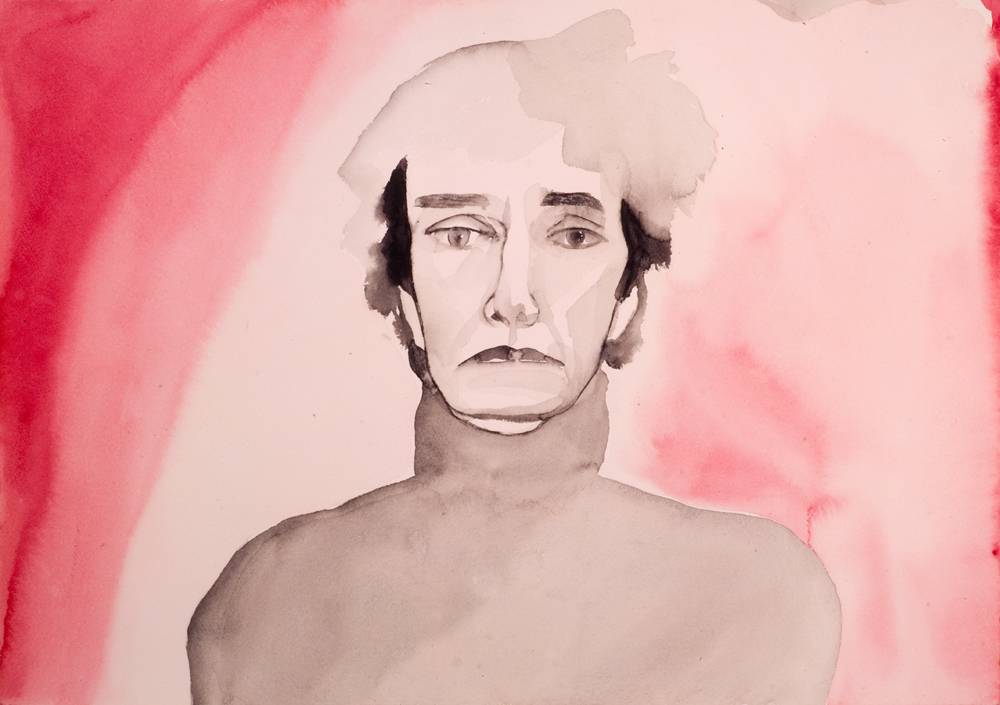

Le fameux déjeuner du 4 octobre 1982 changera la donne. Organisé par leur galeriste commun Bruno Bischofberger, ce moment d’échange passionnant inspire immédiatement les deux artistes : avec son Polaroïd, Andy Warhol immortalise Jean-Michel Basquiat, avant de confier son appareil au galeriste pour qu’il le prenne en photo à ses côtés. Jean-Michel Basquiat quitte ensuite les deux hommes avant la fin du repas pour réaliser une peinture dans la foulée, que son assistant viendra leur présenter deux heures plus tard. Sur Dos Cabezas, portrait devenu depuis iconique, le jeune homme s’est représenté à droite souriant et les cheveux hirsutes sur fond bleu, tandis que l’on reconnaît les traits du visage d’Andy Warhol, en grand sur la partie gauche de la toile. Devant cette œuvre, le père du pop art se dit impressionné par la rapidité et la fougue de Basquiat, qui font naître chez lui une admiration réciproque.

Mais la discussion qui scellera leur amitié et leur rencontre artistique aura lieu un an plus tard, de l’autre côté de l’Atlantique. Alors que Basquiat séjourne chez Bruno Bischofberger à Saint-Moritz, le galeriste a la surprise de découvrir sur les dessins de sa propre fille de trois ans la patte du peintre new-yorkais. Une idée lumineuse lui vient : inviter ce jeune prodige de l’art qu’il commence tout juste à représenter à créer des œuvres avec d’autres peintres de renom, afin de permettre à son talent de rayonner davantage. Lorsqu’il soumet l’idée à Jean-Michel Basquiat, très enthousiaste, celui-ci lui cite immédiatement le nom d’Andy Warhol. Le projet tombe à pic pour stimuler le dernier qui, après des années 60 florissantes, se fait désormais plus discret et moins audacieux, réalisant principalement des portraits pour des célébrités et riches hommes d’affaires. Le galeriste suggère également Francesco Clemente, grand peintre italien proche de Basquiat, comme troisième participant au projet. En 1983 et 1984, les trois artistes acceptent alors de réaliser ensemble une quinzaine d’œuvres : leur collaboration tricéphale est lancée.

Warhol et Basquiat, deux artistes qui bouleversent les codes de la peinture

Corps liquides et visages spectraux recouverts de traits frénétiques, symboles et phrases, et d’images photocopiées et sérigraphiées… Dès les premières toiles réalisées par Basquiat, Warhol et Clemente s’affirme une peinture protéiforme dont l’action et les sujets se voient décentrés pour envahir l’ensemble de la toile. A l’heure où le néo-expressionnisme fait florès aux États-Unis, les œuvres du trio se rapprochent de leurs homologues Julian Schnabel, David Salle ou encore Enzo Cucchi, tout en s’en distinguant par leur multiplicité de techniques et leur hybridité formelle. En reprenant le procédé du cadavre exquis – dont raffolaient les surréalistes – sous les conseils de Bruno Bischofberger, les trois artistes participent de son renouvellement en apposant leur patte respective. À tour de rôle, chacun s’empare librement d’une partie de la toile sans informer ses confrères de ses intentions, et attend le passage du dernier pour découvrir la composition finale. Éclectique et composite, leur vocabulaire pictural s’étend ainsi du symbolisme et du fauvisme au graffiti et la publicité.

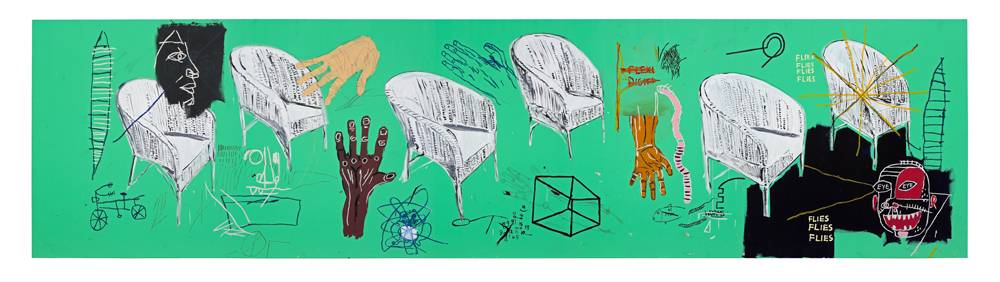

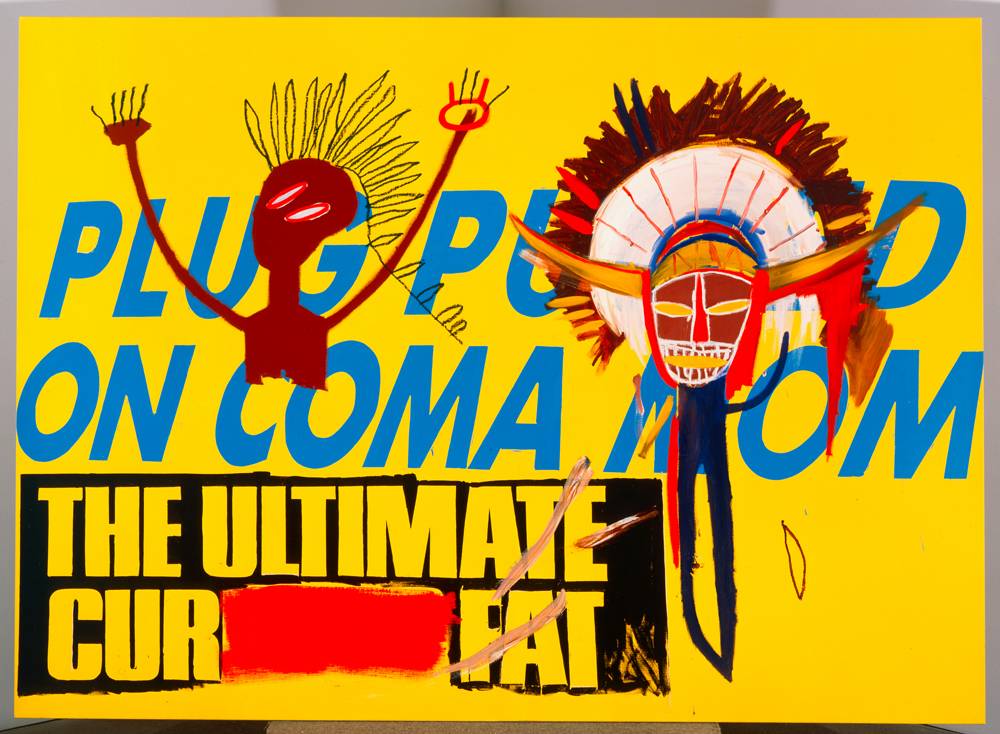

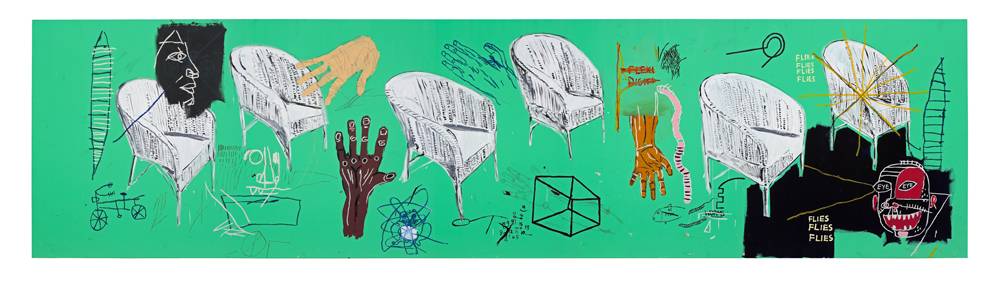

Cette œuvre à six mains prend un autre tournant lorsque, stimulés par ces échanges picturaux, Andy Warhol et Jean-Michel Basquiat décident de prolonger leur collaboration en duo. Au sein de la Factory, où les deux peintres produisent cette fois-ci ensemble, leur geste se libère tandis que les formats de leurs toiles s’agrandissent pour atteindre jusqu’à 8 mètres de large (Chair, 1985) et près de 3 mètres de haut (6,99 et Mind Energy, 1985), brouillant encore davantage les frontières entre beaux-arts et communication visuelle de masse. Là où les figures humaines fantomatiques de Francesco Clemente envahissaient les premières Collaborations et les adoucissaient par leur touche plus académique et symboliste, les toiles de Basquiat et Warhol dégagent de grandes zones vides aux couleurs vives et unies pour favoriser l’expressivité de leur style. La complémentarité des deux peintres triomphe ici plus que jamais, mariant l’esthétique “à vif et directe” presque primitive du premier – lui-même disait s’inspirer des dessins des enfants en bas-âge – et celle “de la distance, voire de l’indifférence, non dénuée d’ironie” du second, telles que les définit Suzanne Pagé, directrice artistique de la Fondation Louis Vuitton. Pour produire à la chaine, les deux hommes trouvent leur rythme : pendant que Basquiat enduit les toiles et les peint au sol, Warhol investit les murs pour décliner les formes qu’il ajoutera ensuite à la sérigraphie.

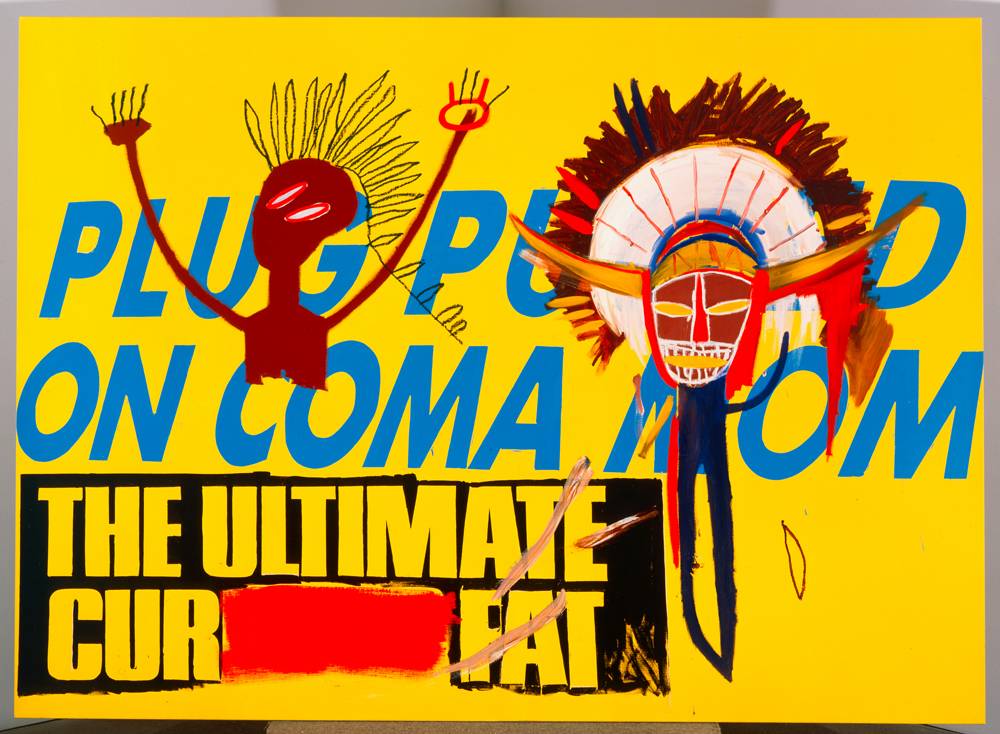

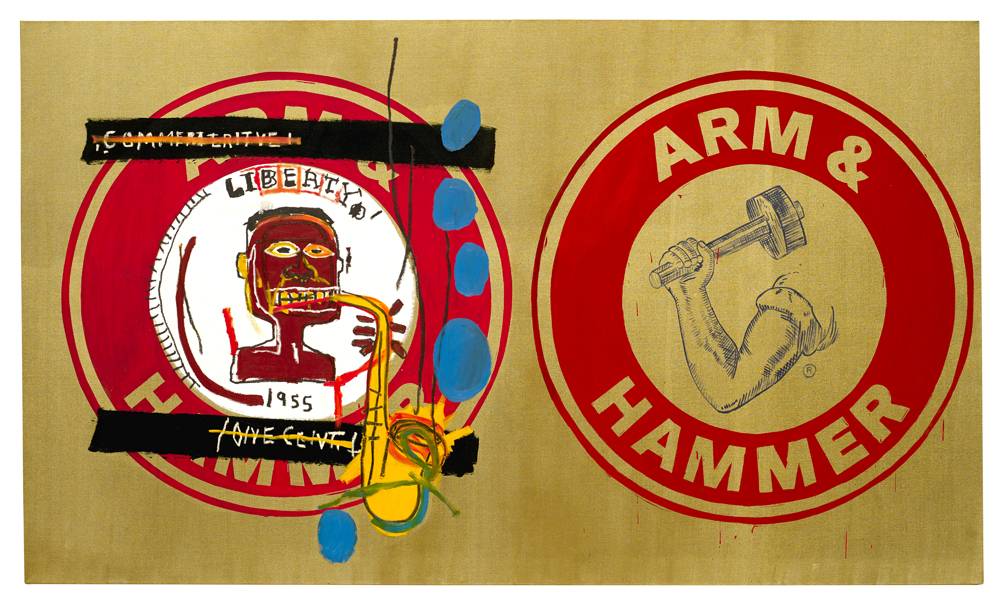

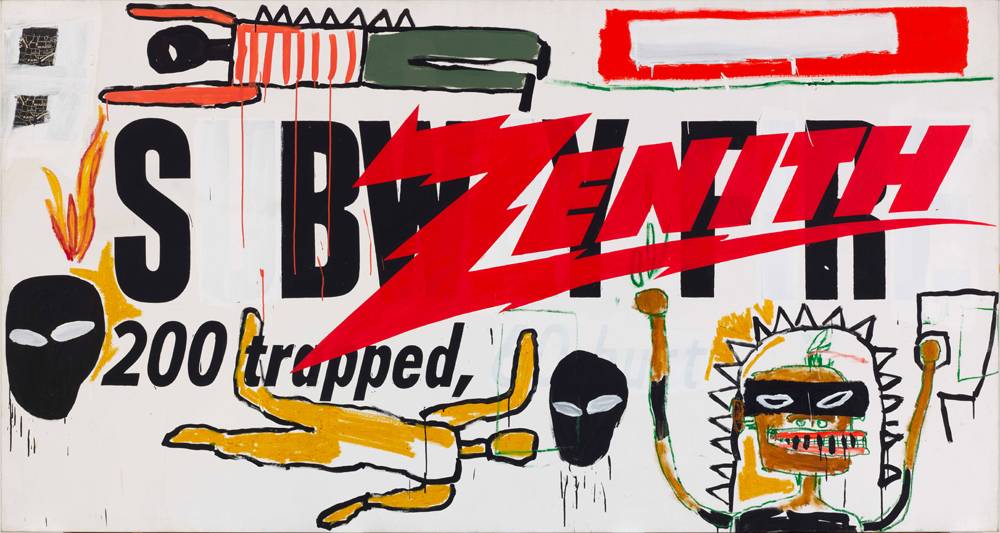

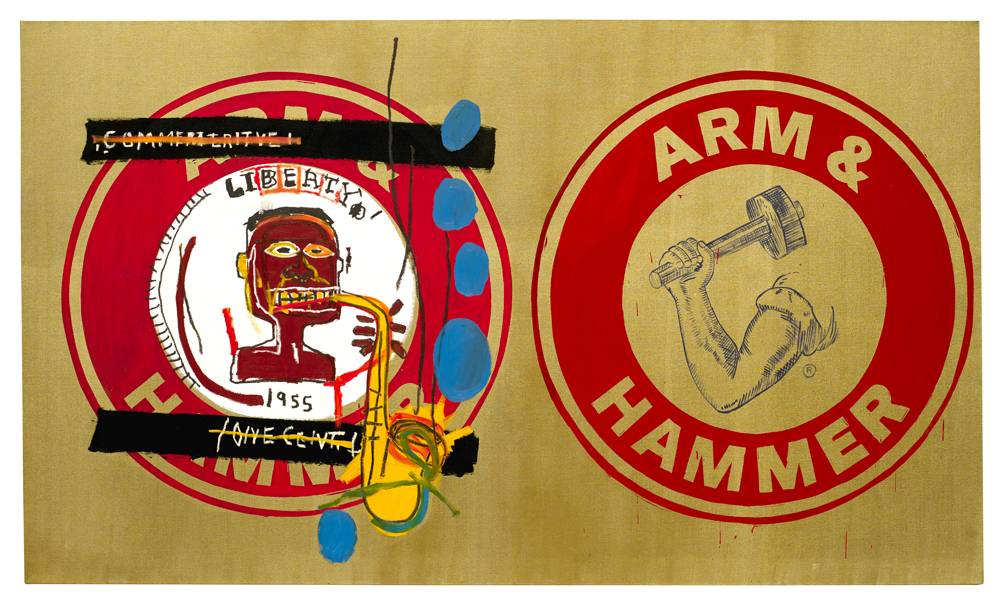

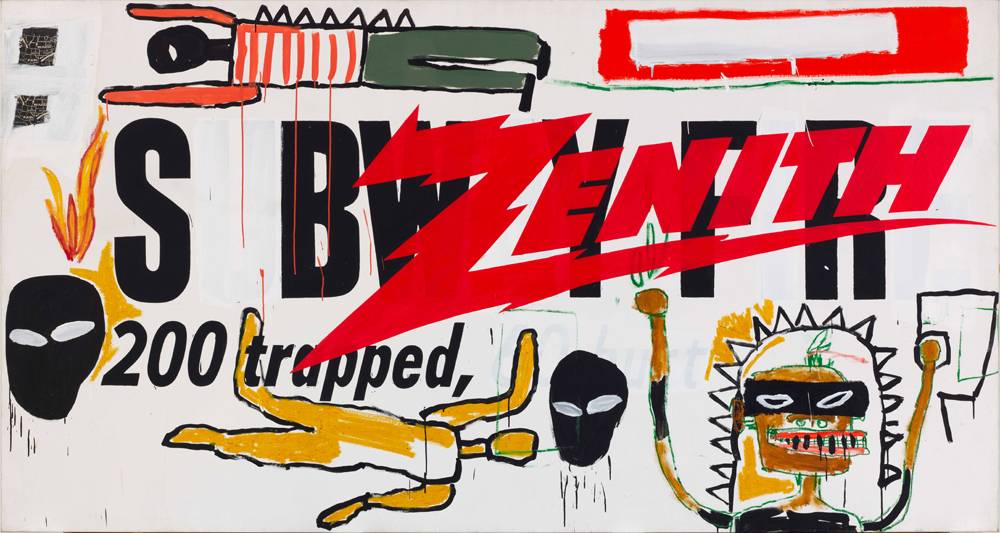

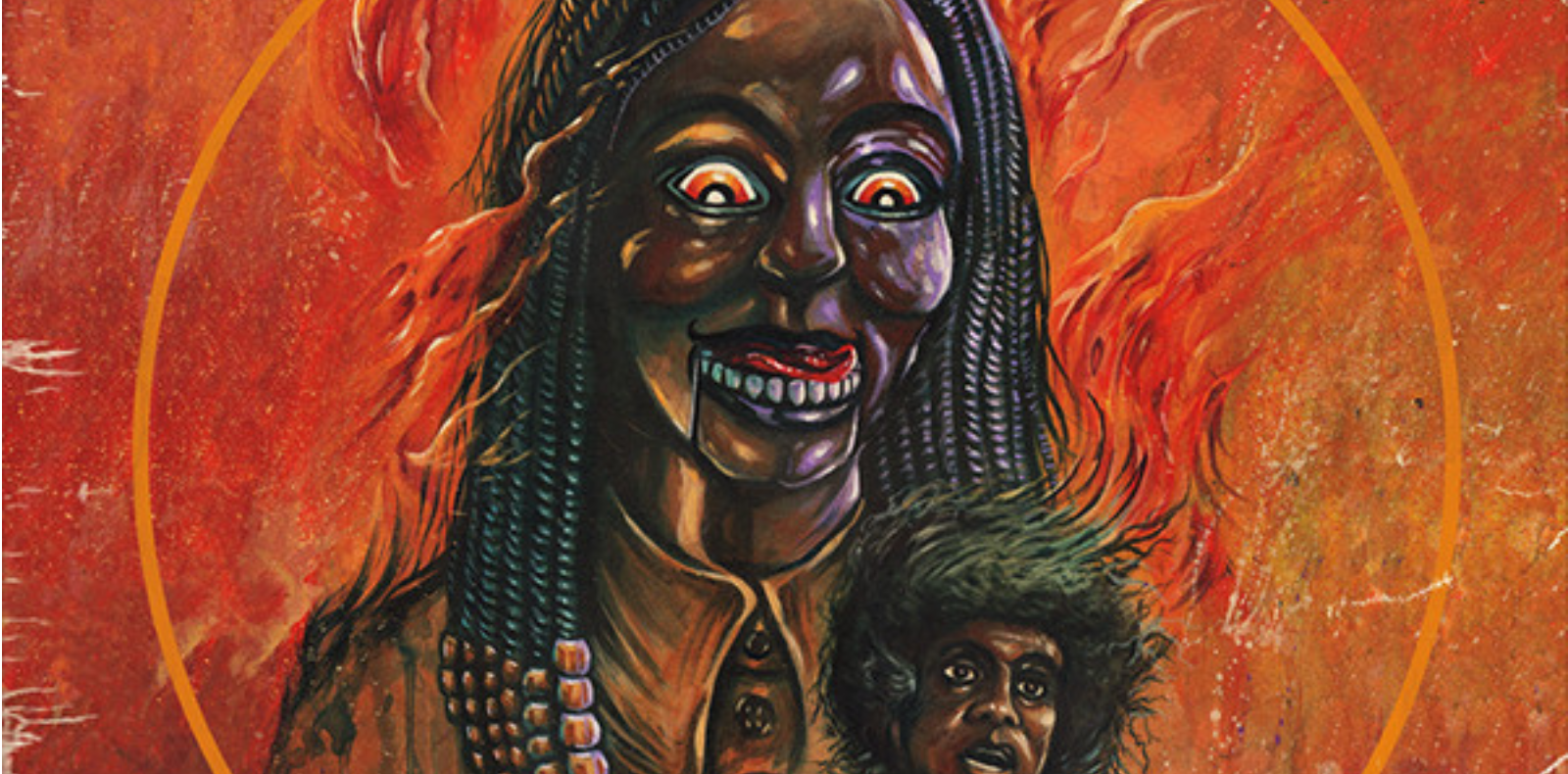

D’un tableau à l’autre, plusieurs éléments reviennent. De Warhol, on retrouve par exemple logo GE de General Electric – immense firme américaine d’énergie – et la carte de la Chine – pays qui fascine l’artiste depuis une décennie par sa culture, son président Mao Zedong les codes visuels de la propagande communiste –. De Basquiat, on voit régulièrement apparaître la banane – hommage à la couverture iconique The Velvet Underground and Nico signée Warhol (1967), dont il tire même le portrait en banane – ou encore les masques africains, auxquels les deux peintres consacrent une œuvre entière en 1984. Régulièrement, les deux hommes se répondent par leur interprétation respective d’un même sujet : une bouche grimaçante remplie de dents pointues de Basquiat répond à un dentier lisse de Warhol, tandis que le logo en éclair de la marque d’électroniques Zénith croise les corps déchaînés par des décharges électriques. Accrochée en ouverture de l’exposition à la Fondation Louis Vuitton, l’œuvre Arm and Hammer, d’après la marque éponyme de produits d’entretien, montre explicitement ce miroir artistique avec deux sujets juxtaposés et encerclés de rouge sur un fond doré : à droite, le bras musclé soulevant une haltère du logo de la marque est ajouté par Warhol, à gauche, un visage noir jouant au saxophone signé Basquiat. Si formellement, les courbes de l’instrument font écho à celles du biceps, les deux éléments proposent surtout deux visions de la masculinité, où l’apparence lisse et ordonnée du logo contraste avec celle du personnage, beaucoup plus expressive et déstructurée.

Un tournant dans la carrière de Jean-Michel Basquiat et Andy Warhol

“Quand Basquiat et Warhol m’ont montré leurs premières collaborations – une quarantaine de toiles – c’était incroyable, se remémore Bruno Bischofberger. Je me suis dit : « ils m’ont caché ça ! »” Au printemps 1985, le galeriste a en effet la surprise de constater combien son idée originale a porté ses fruits, au point que les deux artistes se l’approprient sans même l’en informer. Lorsqu’il expose quelques mois plus tard, pour la première fois, une vingtaine de ces œuvres, la réception critique est presque unanimement négative. L’œuvre très radical du jeune Jean-Michel Basquiat est encore loin de gagner l’adhésion du public et les institutions, “pas encore prêtes” selon le galeriste, se désintéressent complètement du projet. Seuls quelques collectionneurs voient un potentiel dans cette rencontre entre un artiste établi et son protégé. Grand susceptible, Basquiat se voit très affecté par l’accueil mitigé de son travail, met alors fin aux collaborations et prend ses distances avec son aîné. Plus aguerri et habitué aux critiques, Andy Warhol voit toutefois ses limites lorsque le New York Times décrit Basquiat comme “sa mascotte”, qu’il aurait manipulée pour obtenir de lui cette riche production.

Si les deux artistes ne retravailleront jamais en duo après 1985, cet épisode de leur carrière donne un nouveau souffle salutaire à leur pratique. La mission de Jean-Michel Basquiat, qui comptait redonner à Andy Warhol le goût de la peinture, est accomplie : s’il déplore la fin de leur collaboration, le pape du pop art note que le jeune homme “l’a amené à peindre différemment”. “Warhol était un vieux fauve mais il est devenu encore plus sauvage sous l’effet de son enthousiasme pour Basquiat”, ajoute leur galeriste, qui voit d’ailleurs dans les nouvelles peintures du premier réalisées en solo des “collaborations” sans la patte du second. De son côté, le jeune peintre de Brooklyn continue de développer sa pratique de la sérigraphie et de la céramique dans la lignée des pièces qu’il réalisait avec son idole, et collabore avec d’autres artistes de la scène new-yorkaise tels que Keith Haring, Stefano Catronovo ou encore Kenny Scharf sur des affiches, toiles, vases et même vêtements. Basquiat et Warhol resteront amis avant de s’éteindre à la fin des années 80, à un an d’intervalle. Loin d’imaginer l’immense succès posthume qui attend leur œuvre commun.

“Basquiat x Warhol. À quatre mains”, jusqu’au 28 août 2023 à la Fondation Louis Vuitton, Paris 16e.

Standing side by side, their arms crossed with Everlast boxing gloves and shorts on, Andy Warhol and Jean-Michel Basquiat are set for a fierce match on the poster for the “Basquiat x Warhol” exhibition at the Fondation Louis Vuitton. Rather than confronting each other, these two major figures of the New York underground art scene in the second half of the 20th century, here photographed by Michael Halsband in 1985, team up to face the visitors. A powerful way of introducing their prolific artistic collaboration, which began in 1983. For two years, the two artists produced around a hundred “four-handed” artworks, often monumental canvases that link together two complementary approaches and pictorial styles. Until the end of August, the Parisian institution will focus on this rich encounter through an exhibition of 300 works asserting how much this episode has marked the careers of both artists and the history of art.

Because it represents the unexpected encounter between two major artists

Andy Warhol (1928-1987) and Jean-Michel Basquiat (1960-1988) might never have met. In addition to a 32-year age gap, the two artists came from completely different backgrounds. The first one is a native of Pittsburgh, who graduated in fine arts and made his debut in advertising and shoe design in New York in the 1950s. The second one grew up in Brooklyn in the 1960s, raised in a family of Haitian origin, and started his career as a street artist under his now famous signature alias, SAMO. Although 1982 is often cited as the year the two of them first met over lunch, they had already met three years earlier. At the time, Jean-Michel Basquiat was only 17 and spent his days calling on passers-by in the street to sell his postcard collages. One day, he saw Andy Warhol with Henry Geldzahler, director of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, in a restaurant in Soho. Basquiat, who admired Warhol, took matters into his own hands and approached them with two of his artworks, which they bought for $1 each. Although that moment was unforgettable for Basquiat, it wasn’t as memorable for Warhol, who remained rather dubious about the New Yorker’s potential over the following years.

The famous lunch on October 4th, 1982, brought about major change. That moment of passionate conversation set up by their common gallery owner Bruno Bischofberger immediately inspired the two artists – Andy Warhol immortalized Jean-Michel Basquiat with his Polaroid, before entrusting his camera to the gallery owner so that he could take a photo of the two of them. Jean-Michel Basquiat then left the two men before the end of th meal to work on a painting immediately afterward, which his assistant would come to present to them two hours later. In the now iconic portrait Dos Cabezas, the young man is depicted on the right-hand side with a smile on his face and a shaggy hair style against a blue background, while the thick lines drawing Andy Warhol’s facial features stand out on the left-hand side of the canvas. When presented with the artwork, the father of pop art admitted he was impressed by Basquiat’s speed and enthusiasm and would nurture a mutual admiration from that moment.

Yet, the conversation that sealed their artistic collaboration took place a year later on the other side of the Atlantic. While Basquiat was staying at Bruno Bischofberger’s place in St. Moritz, the gallery owner was amazed to discover the New York painter’s stroke on the drawings of his three-year-old daughter. A brilliant idea came up – to invite the young art prodigy, whom he had just begun to represent, to create artworks with other renowned painters, in order to allow his talent to shine through. When he presented the idea to an enthusiastic Jean-Michel Basquiat, the latter immediately mentioned Andy Warhol’s name. The project came at the right time to stimulate the latter, who, after a flourishing decade in the 1960s, was now more discreet, less daring, and mainly realizing portraits for celebrities and rich businessmen. The gallery owner also suggested Francesco Clemente, a great Italian painter close to Basquiat, as a third participant in the project. In 1983 and 1984, the three artists agreed to produce about fifteen pieces together. Their six-handed collaboration was launched.

Because it offers a new take on painting

Liquid bodies and spectral faces covered with frenetic strokes, symbols, sentences, and photocopied and silk-screened images… Basquiat, Warhol, and Clemente’s earliest canvases display a shape-shifting aesthetic, in which the plot and the protagonists are decentered and invade the whole painting. At a time when neo-expressionism was flourishing in the United States, the works of the trio were similar to those made by their counterparts Julian Schnabel, David Salle, and Enzo Cucchi, while differing from them in the multiplicity of techniques used and in their formal hybridity. By taking up the exquisite corpse process dear to the Surrealists and under the guidance of Bruno Bischofberger, the three artists contributed to its renewal by adding their personal touch. Each one of them freely took over a part of the canvas without informing his fellow artists of his intentions. They all waited for the last one of them to paint to reveal the final composition. Eclectic and composite, their pictorial vocabulary ranges from symbolism and fauvism to graffiti and advertising.

Stimulated by these pictorial exchanges, this six-handed work took new turn when Andy Warhol and Jean-Michel Basquiat decided to extend their collaboration as a tandem. At the Factory, where the two painters produced artworks together this time, their stroke was freer as the formats of their canvases increased to 8 meters wide (Chair, 1985) and almost 3 meters high (6.99 and Mind Energy, 1985), further blurring the lines between fine art and mass visual communication. Unlike Francesco Clemente’s ghostly human figures, who invaded the early Collaborations and softened them with their more academic and symbolist touch, Basquiat and Warhol’s compositions expose large and empty areas of bright, plain colors to foster the expressiveness of their style. Here, the complementary nature of the painters prevails more than ever. As the artistic director of the Louis Vuitton Foundation Suzanne Pagé analyses it, the works combine the “raw and direct”, almost primitive aesthetic of the Basquiat, who himself recognized he was inspired by children’s drawings, and the “distance, even indifference, not without irony” of Warhol. Both men found their own pace to produce an extensive series of works. While Basquiat coated the canvases and painted them on the floor, Warhol took over the walls to create a variety the shapes that he would later add to the silkscreen.

From one painting to the next, recurring elements arise. For instance, we find Warhol’s reproduction of the GE logo, from the American multinational energy company General Electric, and of the map of China, a country that had fascinated the artist for over a decade because of its culture, its president Mao Zedong, and the visual codes of communist propaganda. As a tribute to Warhol’s iconic album cover of The Velvet Underground and Nico (1967), in which a banana portrays the band, Basquiat regularly brings the fruit in the picture, along with African masks, to which the two painters devoted an entire piece in 1984. The two men often respond to each other with their respective interpretation of the same subject – Basquiat’s grinning mouth full of sharp teeth echoes to Warhol’s smooth dentures, while the lightning bolt logo of the electronics brand Zenith crosses paths with wild bodies unleashed by electric shocks. Opening the exhibition at the Fondation Louis Vuitton, the artwork Arm and Hammer, named after the eponymous brand of cleaning products, explicitly shows that artistic mirroring with two juxtaposed subjects circled in red on a golden background – on the right-hand side, the muscular arm lifting a dumbbell with the brand’s logo on it was added by Warhol, while Basquiat signed the black face playing saxophone on the left-hand side of the canvas. Although the curves of the instrument echo those of the biceps on a formal level, the two elements offer two conceptions of masculinity above all. The smooth and organized appearance of the logo contrasts with the much more expressive, yet less structured character.

Because it marks a turning point in the careers of both artists

“When Basquiat and Warhol showed me their first collaborations – about forty paintings – it was incredible,” Bruno Bischofberger recalls. “I thought to myself, ‘they hid that from me!’” In the spring of 1985, the gallery owner was indeed surprised to see how his original idea had paid off, to the point that the two artists took it over without even informing him. When he exhibited around twenty of these works for the first time a few months later, the critical reception was almost unanimously negative. The quite radical approach of the young Jean-Michel Basquiat was still far from winning over the public, and the art institutions, which were “not yet ready” for him according to the gallery owner, were completely uninterested in the project. Only a few collectors saw the potential of the encounter between an established artist and his protégé. Basquiat, who was very sensitive, was deeply affected by the lukewarm reception of his work. He decided to put an end to his collaborations and to distance himself from his elder brother. More seasoned and used to criticism, Andy Warhol saw the limits of that collaboration when The New York Times described Basquiat as a “mascot” he had manipulated to gain that prolific production of artworks.

Although the two artists never worked together again after 1985, this episode in their careers gave a new and salutary impetus to their practice. Jean-Michel Basquiat’s mission, which was to give Andy Warhol a taste for painting, was accomplished. Lamenting on the end of their collaboration, the king of pop art confessed that the young man got him “into painting differently”. “Warhol was an old wild animal, but he became even wilder under the effect of his enthusiasm for Basquiat,” their gallery owner acknowledged as he witnessed the former’s new solo paintings as “collaborations” deprived of the latter’s touch. Basquiat, for his part, kept developing his silkscreen and ceramic practice following the same process he previously used with his idol and worked with other artists from the New York scene such as Keith Haring, Stefano Catronovo or Kenny Scharf on posters, vastes and even clothing. The two artists remained friends until they passed away in the late eighties, a year apart. Far from anticipating the huge posthumous success of their common œuvre.

“Basquiat x Warhol. À quatre mains”, until August 28th, 2023, at the Louis Vuitton Foundation, Paris, 16th arr.