5

5

Censored paintings by Betty Tompkins

À l’heure où les images pornographiques sont si facilement accessibles sur Internet, les tableaux de Betty Tompkins, censurés pendant trente ans, commencent à être exposés au début des années 2010. Si l’art contemporain semble le lieu de toutes les transgressions, représenter la sexualité y reste pourtant très difficile.

Par Éric Troncy,

By Éric Troncy.

“On ne montre plus de poils pubiens en public, c’est le plus grand changement.” Voilà ce que rétorque Betty tompkins lorsqu’on lui demande ce qui s’est profondément modifié au regard de l’époque où elle a commencé à travailler – la toute fin des années 60. la question était d’ordre beaucoup plus général, mais, avec une grande concentration, elle répond très précisément au sujet de l’imagerie érotique (ou, disons-le franchement, pornographique) : un sujet qu’elle connaît bien puisque c’est aussi celui de sa peinture, sans exception notoire, depuis plus de quarante années – un choix qu’elle paya au prix fort. À 75 ans, Betty tompkins a observé les divers changements, mais aussi les invariants qui jalonnent l’histoire des relations qu’entretiennent l’art de notre époque et la représentation de la sexualité. des relations complexes, qui la privèrent même de ses tableaux.

L’art contemporain, qui, par nature, est le lieu de toutes les transgressions et de toutes les provocations, fait preuve à l’égard des représentations de la sexualité d’une pruderie qui laisse perplexe. Perplexité que nous inspire également cette époque, où des millions d’images pornographiques sont accessibles librement sur internet, mais où, dans le même temps, l’image de L’Origine du monde, le tableau peint par gustave Courbet en 1866, qui représente le bas d’un corps de femme les jambes écartées et que le musée d’Orsay se félicite, à juste titre, de compter dans ses collections, est férocement censurée par Facebook. Tout invite à penser, d’ailleurs, qu’en se tenant sagement éloignés de la représentation du sexe, ce que les artistes redoutent plus que tout est justement la censure qui, historiquement pourtant, ne leur fit jamais peur, et même les invita souvent à la transgression. mais c’est ainsi : en devenant “contemporain”, l’art a abandonné les représentations scandaleuses au profit de slogans de substitution : on verrait sans s’étonner le mot “pénétration” au mur d’une galerie, plus aisément en tout cas que l’image d’une pénétration. En devenant “contemporain”, l’art a aussi réorganisé sa destination : vers les musées traquant aujourd’hui des publics de plus en plus larges et qu’on ne saurait choquer de manière aussi brutale ; vers des collectionneurs qui ne sont quasiment plus jamais des “amateurs” d’art et de transgressions avant-gardistes, mais des socialites aspirant à une distinction. et lorsque ceux-ci donnent des dîners, ils veulent sans froisser personne que la toile accrochée dans la salle à manger soit, certes, immédiatement reconnaissable, mais aussi immédiatement acceptable et rapidement oubliée – qu’on passe à table !

Les peintures extraordinaires réalisées après 2006 par John Currin (pourtant l’un des artistes les plus chers du marché et dont l’acquisition d’une toile demande d’ordinaire plusieurs années de patience), et qui figuraient des scènes sexuelles rocambolesques exécutées avec la virtuosité des grands maîtres français du XVIIIe siècle, rebutèrent tout d’abord les acheteurs, bien conscients qu’il serait délicat d’exhiber leur Currin à la maison. Quant aux musées… la sexualité y trouve éventuellement sa place, comme dans la majeure partie de l’art actuel, sous la forme de questions, de revendications, de protestations… ou de caricatures et de satires. Car c’est là qu’elle s’exprime dans l’art du très haut marché international, comme dans les sculptures monumentales de Paul McCarthy mettant en scène tout un attirail de mannequins articulés ou de figures se livrant à des ébats inattendus, à l’instar de Train Mechanical (2003-2009), vaste machinerie qui montre un automate à l’effigie de George W. Bush entreprenant le derrière d’un cochon – l’ensemble est couleur chocolat. il faut dire que Jeff koons, toujours lui, décidément, asséna un coup sévère à la représentation de la sexualité dès la fin des années 80, exposant les photographies de ses ébats mis en scène avec Ilona Anna staller, une actrice de cinéma pornographique plus connue sous le nom de Cicciolina, et qui pour l’occasion devint sa femme. Peu habitué aux exhibitions de cet ordre (l’exposition fut annoncée comme un film sur un panneau d’affichage géant), le milieu de l’art, déjà très éloigné de l’avant-garde et de ses provocations, s’indigna – et mit du temps à se raviser.

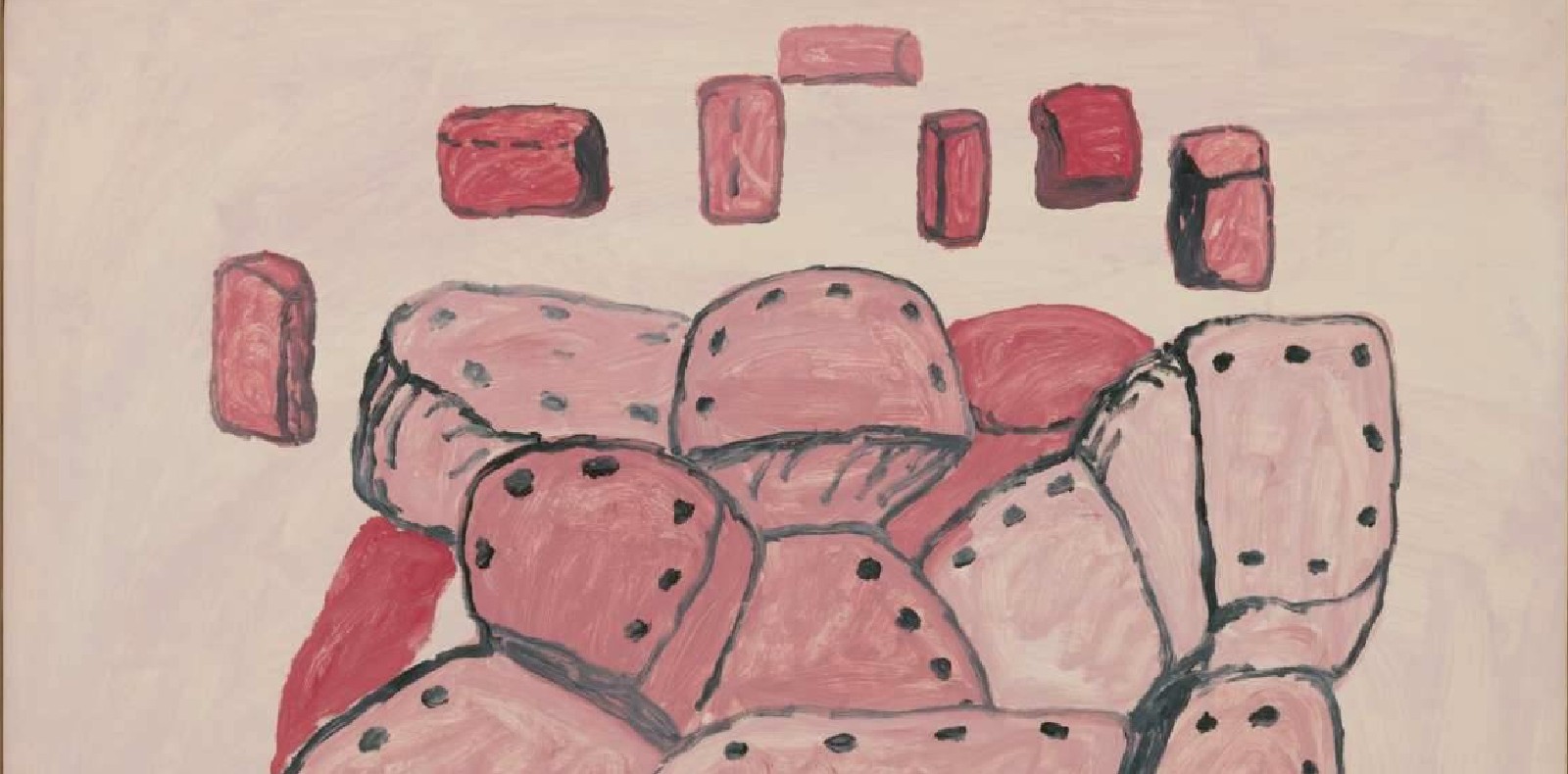

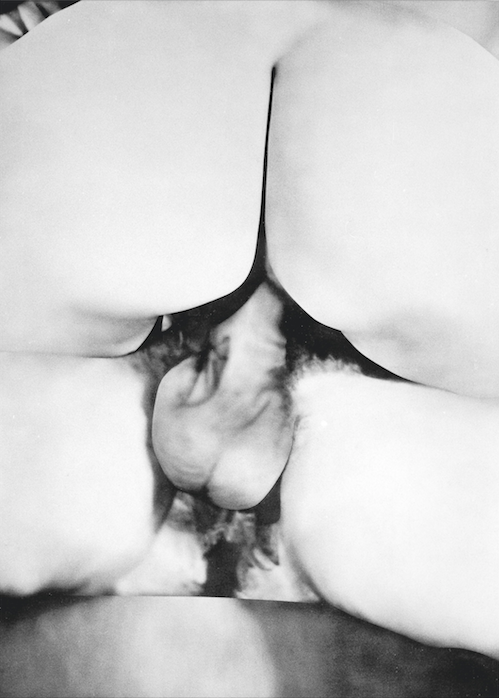

L’art de Betty tompkins est d’une autre nature, encore enraciné dans les avant-gardes à l’époque desquelles, d’ailleurs, il prend naissance. Tompkins étudia la peinture – elle eut, à quelques années d’écart, le même professeur que le peintre américain Chuck Close – dans ce qu’il reste de son admiration pour l’expressionnisme abstrait et Willem de Kooning. C’est le point de départ de ses premières toiles figuratives conçues en 1969, l’année, comme le rappelle le critique Robert Cicetti, où l’astronaute Neil Armstrong fit le premier pas sur la Lune et où il ne devint plus illégal, aux États-unis, de posséder des images pornographiques. Celles dont s’inspire alors Tompkins appartiennent à son mari de l’époque, qui les possédait depuis longtemps avant leur rencontre. Il les avait achetées à Hong Kong ou à Singapour, et se les était fait expédier anonymement via une boîte postale à Vancouver. Recadrées, réorganisées, manipulées, Tompkins les reportait à l’aérographe en s’aidant d’un quadrillage (jamais de projection d’images) sur des toiles grandes comme celles de l’expressionnisme abstrait, en noir et blanc, leurs dimensions les auréolant d’une sorte de sfumato. Les scènes étaient on ne peut plus explicites, cadrées de manière quasi encyclopédique, en gros plan, sans que jamais les visages n’apparaissent. Elles étaient données à voir pour ce qu’elles étaient, sans commentaire, la facture de la peinture ne laissait transparaître aucune intention critique ou discursive, mais, simplement, une forme immédiate de célébration. Bref, le milieu de l’art ne savait qu’en faire. Et surtout, il ne voulait pas les voir. “La plupart des acheteurs que j’ai contactés ont refusé de venir à mon atelier. Je n’ai jamais su si c’était parce que j’étais une jeune artiste, parce que j’étais une jeune artiste femme ou encore si le problème était mon sujet ou le fait que ce soit une jeune artiste femme qui traite de ce sujet”, confie Betty tompkins, qui parvint à participer à une exposition de groupe à New York en 1973 et, la même année, fut invitée à montrer deux toiles en france. Ce qui ne se produisit finalement pas : les œuvres furent confisquées par les douanes, l’entrée sur le territoire français leur fut purement et simplement refusée. Elles restèrent confisquées pendant plus d’une année. “Il m’a fallu un an pour les récupérer. À l’époque, Internet et Skype n’existaient pas. Un appel international longue distance coûtait extrêmement cher, et je n’avais pas d’argent. J’avais vraiment peur de ne jamais les récupérer, mais finalement elles ont été rapatriées. Après cet épisode, malgré quelques personnes qui s’enthousiasmaient pour mon travail, j’étais devenue une pestiférée.”

L’histoire se répéta en 2005 quand trois dessins furent retenus par les douanes avant leur arrivée à Tokyo pour une exposition. Entre-temps, Tompkins connut un long moment de discrétion subie qu’elle veut voir comme une période qui eut ses qualités : “Puisque j’avais passé les trente dernières années hors du système des galeries, j’étais libre de créer sans prendre en compte la tendance ou le marché. J’étais frustrée parce que j’aime pouvoir exposer mes œuvres, mais c’était également libérateur.”

Les choses changèrent au début des années 2000, quand le galeriste Mitchell Algus, célèbre pour ses pugnaces réévaluations d’œuvres d’artistes des années 70 injustement oubliés, s’intéressa à elle. L’invitation que je lui adressai en 2003, avec le critique d’art américain Bob Nickas, à exposer à la Biennale de lyon eut un effet rédempteur – bien que la salle où ses toiles furent exposées avec celles de Steven Parrino dût être gardée par un vigile qui en interdisait l’accès aux personnes mineures ou, disons, sensibles. La conséquence directe de cette exposition fut l’acquisition d’une toile de Tompkins par le Centre Georges-Pompidou – aujourd’hui le seul musée au monde à en posséder une. “Aucun musée américain n’a exposé, acquis ou même accepté une donation d’une de mes œuvres. Et je ne pense pas que cette situation évolue dans un futur proche. Si cela changeait, j’en serais très heureuse, bien sûr, mais je constate que ce n’est pas ce qui est en train de se passer”, confie Tompkins. Ironie totale : c’est la Fuck Painting #1 qu’acheta le Centre Pompidou, c’est-à-dire l’une des deux toiles qui furent bloquées par les douanes trente ans auparavant. Car c’est ainsi que Tompkins décida finalement d’intituler ses œuvres, après avoir révisé les concessions un peu sottes qu’elle fit tout d’abord à la mode. “Le titre original de mes Fuck Paintings était Joined forms. Nous étions à l’apogée de l’art conceptuel, il fallait savoir décrypter. Un dictionnaire était nécessaire pour lire le magazine Artforum. De même, mes peintures Cow/Cunts s’intitulaient Condensed/dispersed, ce qui est à se tordre de rire. J’étais trop littérale et trop sérieuse. Mais il est difficile d’avoir de l’humour quand rien ne se passe comme vous le souhaitez. Même si ce titre me fait beaucoup rire, je les appelle désormais Cow/Cunts. Et je fais toujours référence à mes Fuck Paintings en tant que Fuck Paintings”, expliquait Tompkins au critique Scott Indrisek en 2012. Rien ne sert, en effet, de tenter de conjuguer la provocation et l’excuse, et Betty tompkins n’est pas de cette génération d’artistes qui cherchent avant tout à ne pas froisser le marché pour que rien n’entrave son bon fonctionnement. C’est une artiste, en somme – pas le prestataire de services d’une industrie qui n’existe plus que par son commerce.

“We’re no longer shown pubic hair in public, that’s the biggest change,” explains Betty Tompkins when asked what she thinks has been the most dramatic change from when she started working, right at the end of the 1960s. The question was a general one, but with intent concentration she answered very precisely on the subject of erotic (or, to be frank, pornographic) imagery, a subject she knows well because it has been the subject of her painting, without notable exception, for the last 40 years. A choice that has cost her dearly. Aged 75, Betty Tompkins has observed the various changes, but also the invariables, that have marked the history of relations between the art of our times and the representation of sexuality. Complex relations that have even seen her pictures confiscated.

Contemporary art, which by its very nature is the place for all transgressions and provocations, shows a perplexing prudery with regard to the representation of sexuality. But then our very epoch is just as perplexing: while millions of pornographic images are freely available on the internet, Gustave Courbet’s 1886 painting L’Origine du monde, which shows the lower half of a woman with her legs spread and constitutes a major piece in the collections of the Musée d’Orsay, is ferociously censored by Facebook. Moreover, all the facts seem to suggest, given the way they keep their distance from the representation of sex, that what artists fear most is censorship, even though historically it never scared them and often even encouraged them to transgress. But that’s how it is these days: when it became “contemporary,” art abandoned scandalous representations in favour of replacement slogans; the word “penetration” on the wall of a gallery is far less shocking than a representation of the act itself. By becoming “contemporary,” art also redirected itself: towards museums, hunting for an ever increasing audience that cannot possibly be upset in a full-frontal way; and towards collectors, who are now very rarely genuine connoisseurs of art and avant-gardist transgression, but rather socialites looking for status symbols: when they throw dinner parties they don’t want to offend anyone with the canvas hanging in the dining room, which must be instantly recognisable, instantly acceptable and easily forgotten. Coffee anyone? The extraordinary paintings realized from 2006 by John Currin (one of the most expensive artists on the market whose works usually require years of patience to acquire), which depict extravagant sex scenes executed with the virtuosity of the great 18th-century French masters, were initially shunned by buyers aware that it would be difficult to hang such pieces at home. As for the museums, they might find a place for sexuality, as does so much current art, in the form of questions, claims, or protests, or in caricature and satire.

For that’s how it gets expressed in the art sold in the upper echelons of the international market, such as Paul McCarthy’s monumental sculptures involving a whole panoply of articulated mannequins or figures engaged in unexpected antics, like Train Mechanical (2003–09), a vast chocolate-coloured mechanized piece that features an automaton in the guise of George W. Bush taking a pig from behind. It should be noted that Jeff Koons (yes, him again) dealt a severe blow to the representation of sexuality at the end of the 1980s with his exhibition of photographs showing him frolicking with Ilona Anna staller, a porn star better known as Cicciolina, who for the occasion became his wife. Unused to shows of this order (the exhibition was announced like a film on a giant billboard) the art milieu, already distanced from the avant garde and its provocations, was initially outraged, and took its time to come round.

Betty Tompkins’s art is of a very different nature, still rooted in the avant-gardes of the era in which it was born. Tompkins studied painting – she had the same teacher, but at a different time, as the American painter Chuck Close – under the influence of Abstract Expressionism and Willem de Kooning. That was the starting point for her first figurative canvases conceived in 1969, the same year, as critic Robert Cicetti has pointed out, that

Neil Armstrong walked on the moon and that the possession of pornographic images was legalized in the U.s. The images that inspired Tompkins belonged to her then husband, who had acquired them long before she met him – he had bought them in Hong Kong and singapore and had them sent to him anonymously via a P.O. box in Vancouver. Cropped, reorganized and manipulated, they were recreated by Tompkins in black and white using a grid (never projections) and an airbrush on canvases as big as those of the Abstract Expressionists, their huge dimensions causing them to be haloed with a sort of sfumato. Composed in an almost encyclopaedic way, in close ups, without the appearance of a single face, the works could not be more explicit; they were what they were, presented with zero commentary, with no critical or discursive intent showing through the craftsmanship of the painting – just an instant form of celebration.

The art world had no idea what to make of them, and kept well away. “Most of the buyers I got in contact with refused to come to my studio. I never knew if it was because I was a young artist, a young female artist or if the problem lay with my subject, or if it was because a young female artist had dealt with this subject,” confides Tompkins. Eventually she managed to take part in a group show in New York in 1973 and, that same year, she was asked to show two of her paintings in France. But things didn’t work out as planned since the works were confiscated at customs, their entry onto French soil being flatly refused. And they remained sequestered for over a year. “It took me a year to get them back. At the time there was no internet or skype. An international call was extremely expensive and I didn’t have any money. I was really scared I would never get them home again, but finally they were repatriated. After that episode, apart from a few people who were enthusiastic about my work, I became a leper.” History repeated itself in 2005 when three of her drawings were held by customs before arriving in Tokyo for an exhibition there. In the meantime, Tompkins had lived through a long interval of enforced discretion which she views as a period with its own qualities: “seeing as I’ve spent the last 30 years outside the gallery system, I’ve been free to create without having to consider trends or the market. I was frustrated because I like exhibiting my work, but at the same time it’s been liberating.”

Things began to change at the turn of the millennium when gallery owner Mitchell Algus, famous for his pugnacious re-evaluations of the works of unjustly forgotten artists from the 1970s, got interested in her. The invitation I sent her in 2003, along with American art critic Bob Nickas, to show at the lyon Biennale had a redemptive effect, even though her paintings and those of steven Parrino had to be shown in a room controlled by a guard who refused access to minors and discouraged those with a sensitive disposition. The direct result of the lyon showing was the acquisition of a Tompkins canvas by the Centre Pompidou, which is currently the only museum in the world to own a piece of her work. “No American museum has ever exhibited, acquired or even accepted the donation of one of my pieces. And I don’t think the situation is likely to change soon. If it did change I would be very happy of course, but this doesn’t look like it’s going to happen,” Tompkins says. It’s heavily ironic that the work bought by the Centre Pompidou, Fuck Painting #1, was one of the pair that had got stuck at customs 30 years before. Tompkins decided to name her paintings in this way after revising the slightly silly concessions she had originally made to the trends of the time. “The original title of the Fuck Paintings was Joined Forms. It was like the heyday of conceptual art, you have to understand. You couldn’t read Artforum without a dictionary. And the Cow/Cunts paintings were originally called Condensed/Dispersed, which I now think is hysterically funny. I was too literal-minded and serious. It’s hard to have a sense of humour when nothing is going your way. I think it’s a hilarious title, but I do call them the Cow/Cunts. And the Fuck Paintings I never refer to as anything but the Fuck Paintings,” Tompkins explained to the art critic scott Indrisek in 2012. There’s no point trying to combine provocation and excuses, and Tompkins is not one of this new generation of artists who seek above all not to offend the market for fear of hindering its functioning. she is an artist, full stop, not a service contractor for an industry which now exists solely through its commercial activity.