9

9

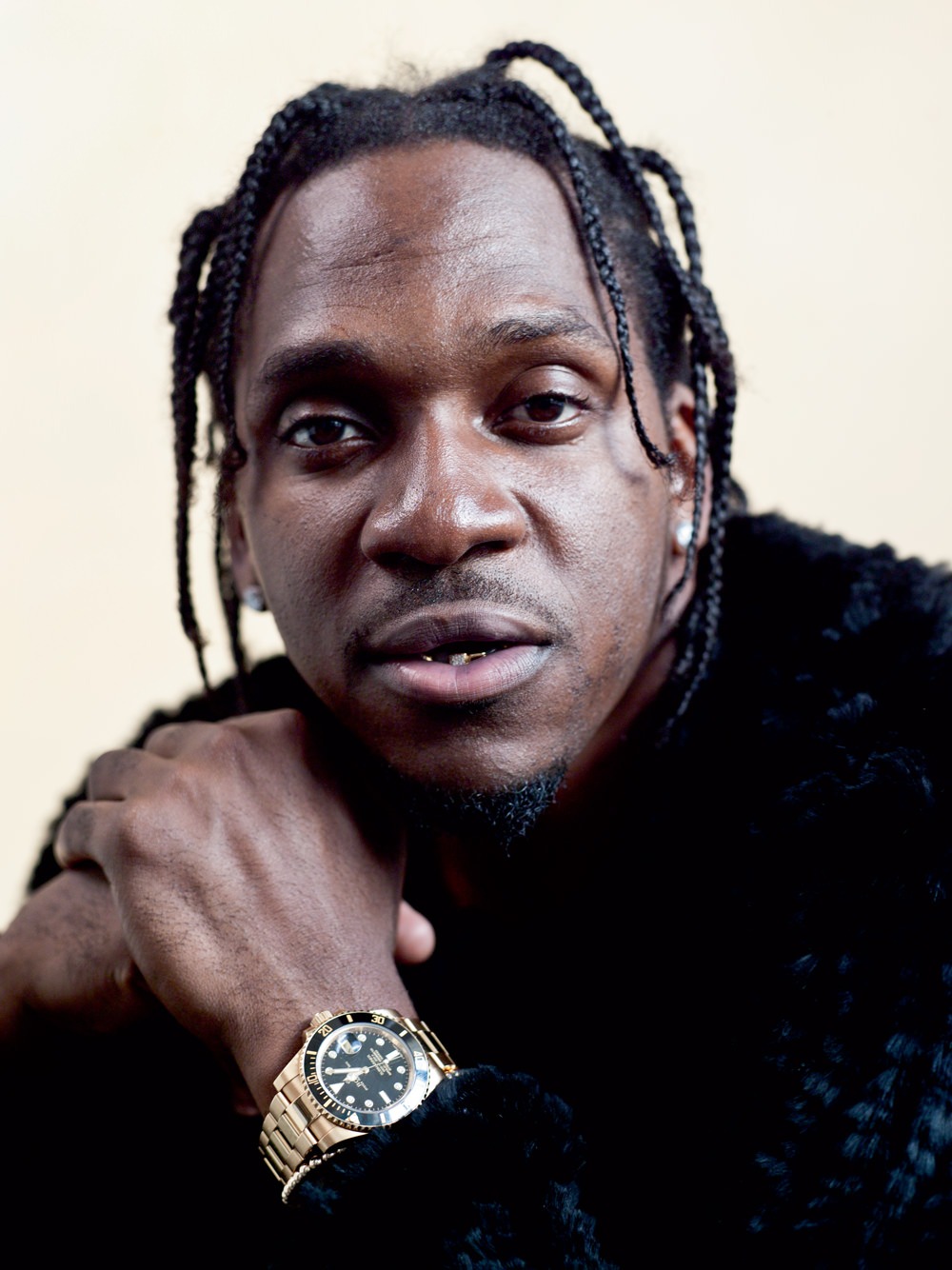

Meeting with Pusha T

At the age of 38, rap star Pusha T has already lived several lives – initial success with the Clipse, followed by a sudden break-up, and then a solo renaissance thanks to Kanye West. Influenced by recent events in Baltimore, his much-anticipated second album, King Push, confirms his political awakening.

“Funeral flowers, every 26 hours, being laid over ours. Born to protect and serve, but who really got the power?” Pusha T recites his verse in passionate, precise syllables. He’s cruising across the bridge from Brooklyn to Manhattan in a black luxury SUV, but his mind is hundreds of miles away, thinking about burning buildings in Baltimore. “I ain’t got no march in me. I can’t turn the other cheek,” he raps, his voice rising in rhythms that echo Malcolm X. “ Why they testing your patience? They’re only testing my reach.” These are the lyrics to Sunshine, from the rap star’s upcoming second solo album, King Push. He wrote them after watching the people of Baltimore rise up this spring against the murder by police of a young black man named Freddie Gray, and against the decades of systemic racism that led to that moment. While President Obama tut-tutted the protesters who took the streets with rocks and fire, Pusha identified with their anger. “It’s the Chuck D perspective,” he says. “I don’t think that America understands how fed up young, black, aggressive men are right now. People are tired of being victimized. And you’re dealing with a generation of young people – these kids are going to act, and it can definitely get worse.”

Explicit radical politics are a new theme for Pusha T, but his 16-year career has proved that few rappers are better at summoning righteous outrage. From the late 90s onward, he was known as the louder, bolder half of the Clipse, the highly respected Virginia rap duo he formed with his brother Gene (known at the time as Malice). “My brother is five years older and wiser,” says Pusha, who was born Terrence Thornton. “He was always the voice of reason. I was the brash one.” That combination powered three acclaimed albums, all largely about the thrills and risks of selling cocaine. Many artists before and since have romanticized that life; no one has portrayed it with such rich, human complexity. About three years ago, his brother found God, changed his stage name to No Malice, and broke up the Clipse, despite Pusha’s objections. “I would never have done that, ever,” Pusha says, still sounding a little bitter about the split. The Thornton brothers remain close, speaking by phone every morning, and reports of a possible reunion reached the press last year. But Pusha says the Clipse’s story is over for good. “ I don’t see us back in the studio making music together,” he says. “I’d love to, of course. But we’re at two different places. That’s just not on the agenda.”

In the meantime he’s built a formidable solo career, starting with 2013’s My Name is My Name. Although the breakup saddened him, it also pushed him forward: Pusha admits that the end of the Clipse forced him to evolve toward new subject matter and more expansive sounds. “Having my brother around was a crutch for me – it was Clipse or nothing,” he says. “Without him around, I play the game differently.” He’s had a powerful patron on that path in Kanye West, who signed Pusha to his G.O.O.D. Records imprint in 2010 and oversaw both My Name Is My Name and King Push as an executive producer. Pusha talks about Kanye the way art historians describe Michelangelo staring at a rough block of Tuscan marble until he saw David. “Kanye sculpts things,” he says. “You only have to give him an iota of something great, and he knows how to take that and turn it into a rainbow.”

The SUV pulls up at Cipriani, a tony Italian spot in downtown Manhattan, and Pusha – comfortably chic in a colourful print jersey from his own Play Clothes line, distressed Saint Laurent jeans, and white King Push Adidas sneakers – takes a seat and orders a free-range chicken dish and salad. Heads turn as Pusha and his crew notice Katy Perry and Hollywood producer Harvey Weinstein chatting one table away. This glamorous realm is worlds away from the Thorntons’ hometown of Virginia Beach, Virginia. “You have to remember, I’m not from a place where stars come from,” Pusha says. Some of his earliest memories are of watching his big brother trade verses with friends, but he didn’t think it would lead anywhere. When they quarrelled, Pusha would throw his brother’s rhyme notebooks in the trash. “I’d say, ‘Why are you writing raps? That’s for people on T.V.’”

In fact, their neighbourhood was an extraordinary hotbed of musical talent. Timbaland and The Neptunes’ Pharrell Williams and Chad Hugo – teenagers at the time, later to be recognized as three of the most influential and successful producers in the history of popular music – all lived close by. In primary school, Pusha would ride his bike to Timbaland’s parents’ house, and sit by while his brother made music there. A few years later, Pusha began rapping himself at informal sessions with his brother and Pharrell – supplementing his childhood love of Run-DMC’s direct, declarative style with intricate wordplay influenced by Rakim and Andre 3000. “I was going to the studio every day by then,” he says. “I didn’t drop out, but skipping school was just what you did.”

By the late 90s, the Neptunes had enough clout to get the Clipse a major-label recording contract. They released one single – 1999’s The Funeral, a stoic tribute to several friends who died young – before the deal fell through. Pusha and Malice kept their heads down and re-emerged in 2002 with Grindin’, their breakthrough hit. Punching and jabbing over a revolutionarily minimalist beat from the Neptunes, they found a sound that appealed to inner-city dope boys and bourgeois suburban rap fans alike. After that came one of the modern music industry’s most infamous nightmares: their superb second album, Hell Hath No Fury, was held in limbo by contractual complications for an agonizing four years. “It was frustrating as hell,” says Pusha. “I had friends tell me, ‘Yo, I forgot you still rapped.’”

Hell Hath No Fury won rave reviews on its eventual release in 2006, but it failed to perform commercially. Tensions mounted after a federal drug bust snared many members of the Clipse’s inner circle in April 2009, and the brothers parted ways after releasing their third and final album that year. Their former manager, Anthony Gonzalez, was ultimately sentenced to 32 years in prison for his role in running a $10-million cocaine and marijuana trafficking operation. “Everybody that I came into the music game with is in jail now,” Pusha says.

In recent years, he’s grown close to prison reform advocate Tony Lewis Jr., whose father was once the right-hand man of notorious Washington, D.C. crack kingpin Rayful Edmond. Their friendship influenced King Push’s Coming Home, where Pusha raps with rare honesty about the challenges facing ex-dealers who are released after decades behind bars. “I don’t hear the ups and downs from other rappers,” he says. “They don’t tell about the losses.”

The sense of loss is even more acute on the new album’s Santeria, born from the grief and fury that Pusha went through after his tour manager, De’Von Pickett, was stabbed to death outside a Philadelphia bar this February. “He was a real church-going guy, very humble,” Pusha says of Pickett, who also worked closely with artists such as Nicki Minaj. “I’m used to death,” he continues, “but I like things to have a rhyme or reason. A random act of violence to somebody who’s not in that life – that doesn’t sit well with me. It hurts, man.” He feels that the incident changed him, perhaps forever. “This was a tough year for me,” he says, speaking quietly. “I think I grew up as a kid desensitized to everything wrong. Death, drugs – I didn’t really think about it. Now I’ve been re-sensitized. Things touch me now.”

At 38, Pusha has been rapping professionally for nearly half his life. And he’s adapted to rap’s changing terrain better than most. Pusha is realistic about his position in the music business. Like most artists today, he can’t count on album sales to make ends meet. “I don’t sell all the records,” he says. “I really have to tour.” But he’s proud of his work on King Push, confidently calling it the best rap album of the year. “ My biggest challenge in not being with the Clipse is trying to fill the void that my brother left,” he says. “I tried my best on My Name Is My Name; I think I got it on King Push. People are going to see that I have a lot more to say.” He leans in and smiles, before mischievously exclaming, “I’m the last rap superhero left.”

King Push, by Pusha T, out soon.