12

12

Interview with Takashi Murakami, a pop icon

Interview by Dan Thawley,

Portrait Sofia Sanchez & Mauro Mongiello.

Published on 12 September 2018. Updated on 18 June 2024.

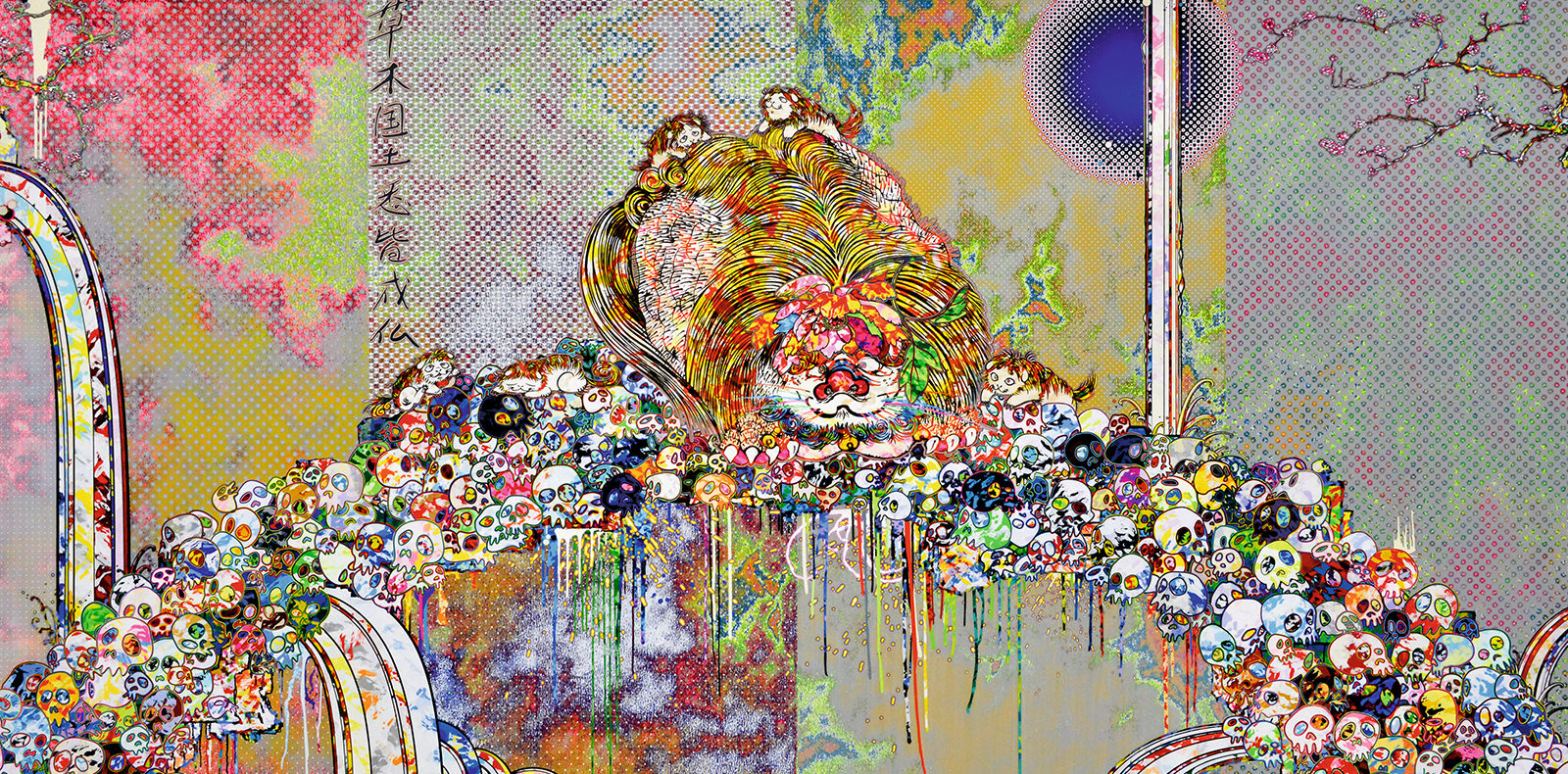

Alongside the doyenne of the dot, the venerable Yayoi Kusama, Takashi Murakami is undoubtedly Japan’s most famous living artist. His practice has, since the mid 90s, questioned the crossroads of Japanese and Western culture, examining the popular tendencies of both through his ultra-slick transmogrification of Japanese painting, cartoons, comics, sexual fantasies and social commentary.

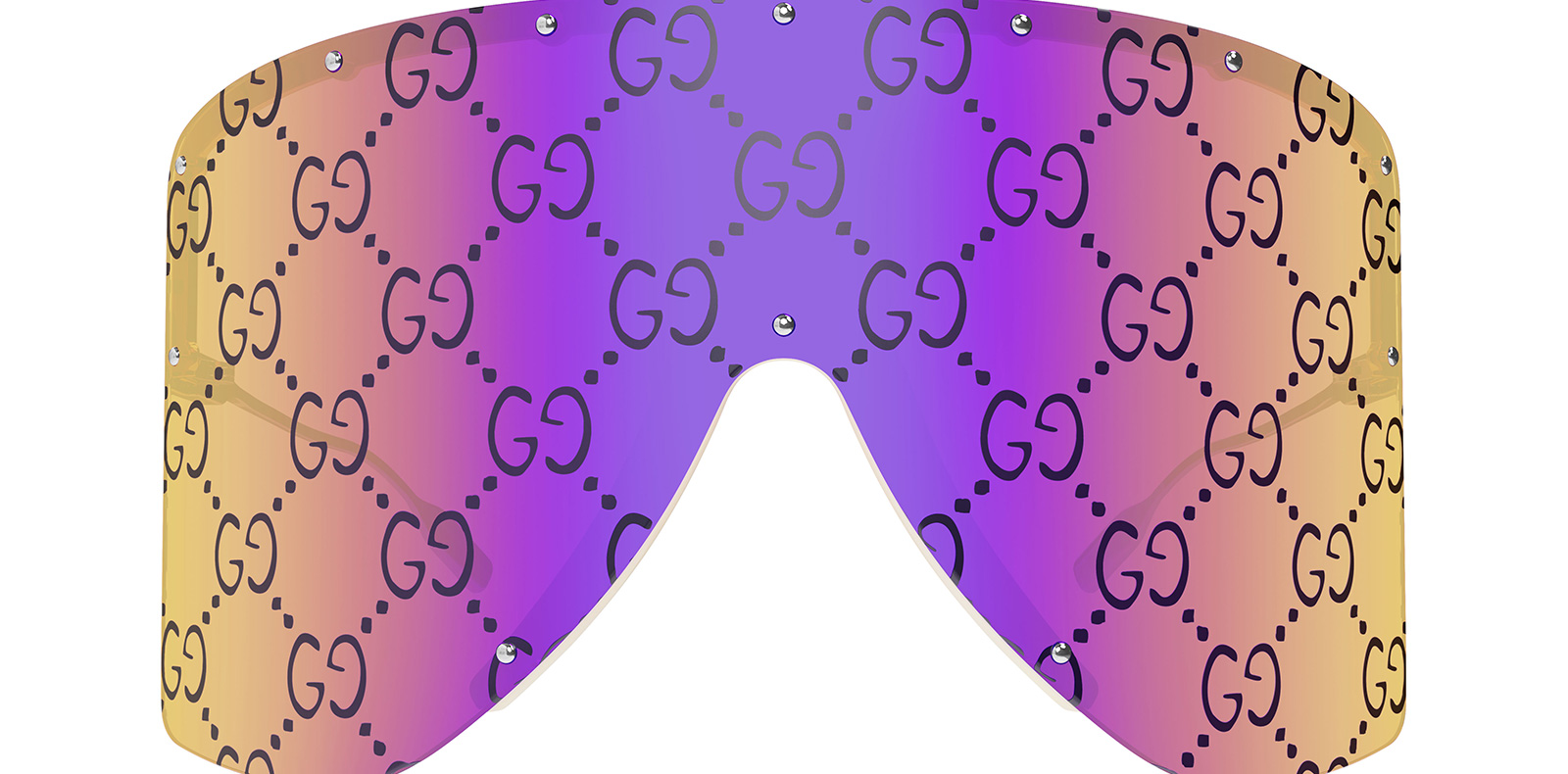

Though now 56, and his life’s work an extraordinarily prolific global empire, Murakami has never stopped exploring new ways of spreading his “Superflat” message, collaborating in particular with fashion and music luminaries such as Issey Miyake, Marc Jacobs at Louis Vuitton, Pharell, and also Kanye West.

Mixing highbrow and popular culture, Murakami’s work continues to map the evolution of popular taste, and his latest collaboration is a testament to his unrelenting curiosity: a series of sculptures and paintings that fuse Murakami’s heraldic Japanese symbols with the graphic language of the American DJ and creative director Virgil Abloh. First presented at Gagosian Gallery in London this February, the pair’s second partnership opened in Paris in June – a coincidence, Murakami says, with respect to Abloh’s début fashion show for Louis Vuitton’s menswear line having fallen just days after, a fact that only increased the exponential hype surrounding the collaboration.

A third show is slated for L.A. in October, proving that Murakami’s love affair with “hype beast” culture is not over yet. With his finger permanently on the pulse of the Zeitgeist, Murakami is attracting a new generation of “Superflat” fans (Abloh included) to his supercharged, multiform art practice.

Numéro: Can you say something about how you developed your highly personal Pop style? Was it through looking at Western artists or did you develop your artistic language from an inherently Japanese perspective?

Takashi Murakami: Before World War II, the centre of art was Paris, and the artists at the forefront of the art world were based there. After the war, Abstract Expressionism came along. Pop Art was supported by the incredible wealth that arrived in the American economy after they won the war. This allowed Pop Art to develop in the 60s and 70s, with the powerful economy literally allowing it to pop up! In Japan, after losing the war, we were really looking towards, and envious of, Pop Art. Even when the bubble economy came and there was huge growth, it still collapsed and became flat. Looking at that critically was how I came up with the concept of “Superflat.” It’s about culture-flattening. So, when you ask me what Pop means to me, I get stuck on American Pop Art, and it’s hard for me to go beyond that.

Did you want to reject notions of American Pop Art with your practice? Or did you integrate it?

My starting position, before my début on the American contemporary-art scene, was difficult. During the 90s, American contemporary art was very strong and I felt like I was part of a movement of third-world artists, like Rikrit Tiravanija from Thailand or Felix Gonzales Torres from Cuba, as well as artists from mainland China. We were from minor countries, but it was a wave, and I was a part of that wave. It was a time when I was learning to understand the system and where it would fit in art history. When I came to New York, sponsored by the Asian Culture Council, I saw a show by Bob Flanagan at the New Museum. He was about 36 or 37 at the time, and worked a lot with ideas of sadomasochism. That show was a huge influence on me, as before then I thought that the art world was just about painting and sculpture. His installations were shocking – there were erect penises, and self-harm, and during the show he would sit in a room of the gallery in a bed and talk with the audience. This was a completely new experience for me, to see videos of an artist and his wife all dressed up in bondage gear – it was a different world. It made me change my mind. Before I thought I had to follow a certain path through art history, but artists like Bob were all about absolute originality. I looked at myself and asked, “What is there that’s original about me?” That’s how I found my style.

“The Japanese mentality towards creativity is very complex, and after losing World War II there was always the issue of both pride and jealousy.”

Did Flanagan’s show at the New Museum help you to deal with ideas of censorship in your work?

That show was a break in the censorship in my head. That’s why I started doing pieces which involved things like masturbation and the milk jump rope. The people in my head said, “Yes, you can do it!”

How did Japanese people respond to your work in the beginning?

Did they react negatively or did they celebrate it? They never celebrated it, until now. The Japanese mentality towards creativity is very complex, and after losing the war there was always the issue of both pride and jealousy. That’s why, when I was a success in New York, there was a backlash. People accused me of stealing Japanese culture. But when I look at Warhol, it’s the same thing. That’s why, whe n War hol was alive, American people hated him. For them it was packaging. In the art world, people have to package what’s going on. When I was getting a negative reaction in Japan, it made me very depressed. I had 25 years of this pressure.

Did you ever think about leaving Japan and rejecting your own culture?

Yes, that’s why I have a green card now. But at the same time, I can’t live without Japanese food! So this is a very real problem.

How much of the year do you spend in Tokyo?

My studio is outside of Tokyo. Recently I’ve been spending two weeks a month in Tokyo, and two weeks travelling elsewhere. It’s too much, I’m getting old! If I were 36, or 40, it would be fine, but I’m not anymore.

How many people work for you today?

A lot of people if you include the New York studio. Something like 300, as I have nearly 150 working on my movie work – live-action and animation stuff. The painting studio is about 50 people.

Your idea of “packaging culture” is interesting. In that sense, how do you approach the scaling and value of your work for different audiences, from large-scale museum pieces to souvenirs?

Basically, in Japan, there are no super-rich people. After the bubble economy in the late 80s, a few people made a lot of money, but when it crashed they lost everything. There were many suicides. The repercussions of World War II meant that the country was never able to build up significant wealth for the next generation until more recently. Rich people escaped to New Zealand, Singapore and Canada. So for me, in that cultural climate, postcards and souvenirs are art. That’s why, in my head, they’re on the same level. When I came to the U.S. and Europe, I was surprised at how super-rich people escape paying their taxes. This was difficult for me to understand. A turning point for me was the Sotheby’s auction in New York, where my one of my sculptures sold for $16 million. I couldn’t understand the price. When I sold the sculpture myself, I got $20,000. And the resale was $16 million! Of course I didn’t actually get that money, but in Japan it was headline news as a record sale. This was before Internet gossip, but people were bashing me. He got the money! He is cheating Western people! He is using strange Japanese sexual and anime culture! This is why for me posters and souvenir T-shirts and things like this become a completely normal way to communicate my creativity.

“People accused me of stealing Japanese culture. But when I look at Warhol, it’s the same thing. That’s why, when Warhol was alive, American people hated him. For them it was packaging. In the art world, people have to package what’s going on. When I was getting a negative reaction in Japan, it made me very depressed. I had 25 years of this pressure.”

When did your art practice first become involved with fashion?

The very first time was with Issey Miyake in 2000. I gave them patterns, like the eyeballs, and some characters. No flowers yet. They made raincoats, bags and sneakers for men. Jef f Koons once told me how impressed he was with the craftsmanship when he worked with Louis Vuitton, how he could feel the emotion in the stitching and the craft as much as he could in one of his other sculptures or art pieces.

Do you feel that when you collaborate with fashion?

Before I collaborated with them, I had never heard of Louis Vuitton. But my assistants said, “Takashi, Takashi, you have to do it! Louis Vuitton is one of the dreams of Japanese women. They love it!” But I couldn’t understand what these brown-coloured bags meant. At the time Marc Jacobs had been there for three years, and I couldn’t understand the brand, but I visited the company often as they would invite me to parties. I’m a geek. That’s why I don’t fit in at parties. But I was thinking that my experience with them was good. It’s interesting what Jeff Koons said about fabrication, but another thing about Louis Vuitton and LVMH is the high quality of their communications. I remember when I used to speak to Yves Carcelle, he would wake up at 6.00 a.m. to work on international communications, then from 9.00 a.m. he would start meetings in Paris, then he would work through the night for events and parties. I asked him, “When do you sleep?”, and he said, “On airplanes!” Perhaps this is why he died so young, because of the lifestyle. And there are a lot of people who work that way in the company, and it creates a different level of communication quality and build-up. I learned a lot about how to make a brand from him and from them. Branding isn’t just about sales, it’s about the artist and their personal branding too.

Do you like art fairs?

Visiting art fairs is a lot of fun for me, but I also have my own gallery, Kaikai Kiki. I like to have a booth and choose artists to sell at the fair – that is a very deep way for me to communicate with my audience. I really love that invol ve me nt. I re pre se nt Japanese artists like Madsaki and Ka zumi Nakamura, Mr., Otani Workshop, things like that. You are showing your second collaboration with Virgil Abloh at Gagosian.

Did you plan the suite of shows in advance or did they develop organically?

We did the first show in London and because of its success we decided to do a second show in Paris. This season it was a complete coincidence that Virgil got the job at Louis Vuitton at the same time. Next, we want to make LED and neon works, for the third show. How did you meet Virgil? He came to my studio the first time over 15 years ago with Kanye West. At that time he was an intern. Last year we met a second time at the MCA Chicago, as the same curator, Michael Darling, was working on my exhibition and his show there. He reminded me that he had come to Tokyo, but I still didn’t know anything about Virgil or who he was. The next time we met was at a talk during ComplexCon last November, when he was speaking about education, and the fact that kids in Chicago when he was growing up didn’t have a lot of galleries and other creative outlets. Then he explained how seeing my Louis Vuitton collaboration opened his eyes to something completely new to him. And nobody had ever said that to me before. When I was working on that collaboration, the art world was very cold, they found it too commercial. But one of the Artforum editors, Scott Rothkopf, who is now a director at the Whitney, wrote about my collaboration because of all the bootlegs and copies of them that he saw in Venice and photographed. It made the front page, and for me that felt like being a part of art history. Although the project itself was still not considered important in the art world, both Scott and Virgil thought it was, and I was so touched. So I asked him to make art together, and he said “Yeah, yeah, this is great, this is great.”

“I’m making a TV series with 15 episodes, and I’m up to number four. It should be finished in 2020. It is called Six Hearts Princess, and it’s a Sailor Moon-style story.”

Was it your first time at ComplexCon?

2017 was my second year. It is completely shocking, as everybody knows who I am! And I thought, “Why?” When I was young I was a geek, and so I know what it’s like – and they are like I was – and they are coming up to me all excited and shaking saying, “You are Takashi Murakami!” For me it was a big question. But then several months ago I realized why – it was because of Kanye. That’s why they know who I am. Sneaker heads love my plush toys and my merchandise, and I realized this is also one of the reasons. But the biggest is my collaboration with Kanye. Marc Ecko, the cofounder of ComplexCon, and I met at his New York office, and it was a complete coincidence as I had found Complex on Facebook through the way they would mention Kanye West gossip. It was super-strange gossip, every day. Today’s Kanye! I found it very funny, because he is a very strange person, and when I collaborated with him I had a lot of strange experiences. Anyway, I became interested in Complex and Marc asked me to take part in their event. I agreed as I wanted to understand more about their culture, and I went along. My merchandise sold out very quickly – I was surprised, they were surprised! So, last year we set up for bigger sales. Virgil and I did a silkscreen event, and I couldn’t understand it – for me it looked like student work, but everybody loved it. Virgil’s concept is very direct. His concept is education for young people. That was a good thing about the Louis Vuitton runway show, how he invited all the Parsons students. This is impressive.

Can you tell me more about your moving-image work? How long have you been working on it?

Probably seven or eight years for the 3D studio. But I started the animation studio nearly 15 years ago. But I have no talent for it, which is why I have n’t done a n ex hibition! [Laughs.] But the LED works in the show with Virgil are done by the animation team, so we have a long experience with that sort of work. My background is geek stuff – Star Wars, Japanese animation, manga, etc., so when I came into the contemporary-art world I was twisted towards something, but I want to reverse that and look back at my own culture and myself. Which is why I really want to make animation and live-action narrative. Before the big tsunami in 2011, I already had an animation studio, but after I had a reason to produce a narrative because I had big questions about what is a story, what is religion? When I think about a painting or a sculpture, it’s one idea, whereas a film has many ideas. Actors, actresses, musicians, sound effects – many elements. Right now I’m making a TV series with 15 episodes, and I’m up to number four. It should be finished in 2020. It is called Six Hearts Princess, and it’s a Sailor Moon-style story.

How else will you be keeping yourself busy this year?

I have a solo show at Gagosian Hong Kong in September, and then the third show with Virgil in L.A. in October, and in November an exhibition at Emmanuel Perrotin’s gallery in Shanghai. I also have several museum projects, some in South America. I’ll go on holidays to a quiet island in the south of Japan, with bad-taste food and absolutely no one to bother me!

Takashi Murakami at Gagosian Hong Kong, 20 September–10 November.