21

21

Surrealism: one hundred years of a movement that is still very contemporary

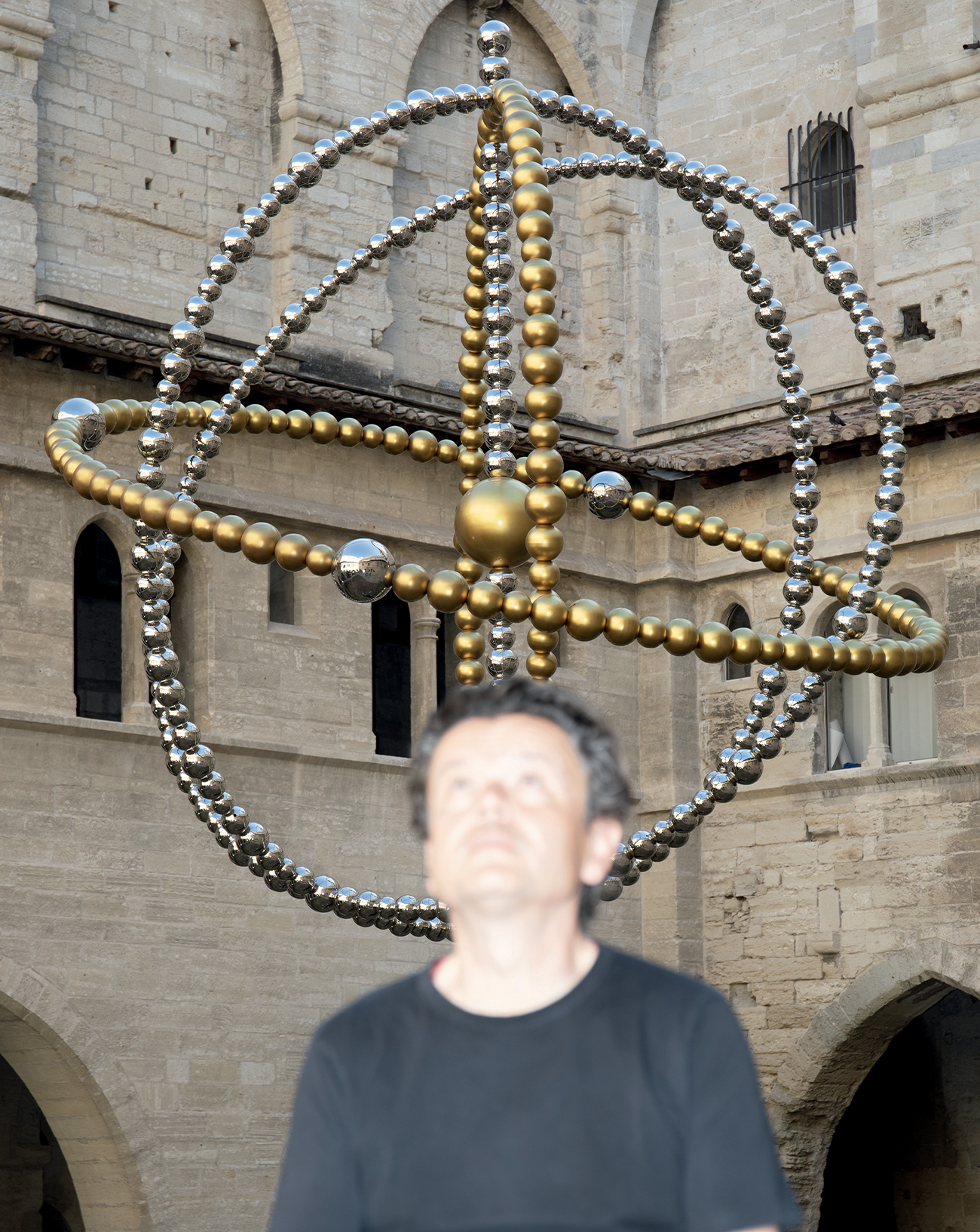

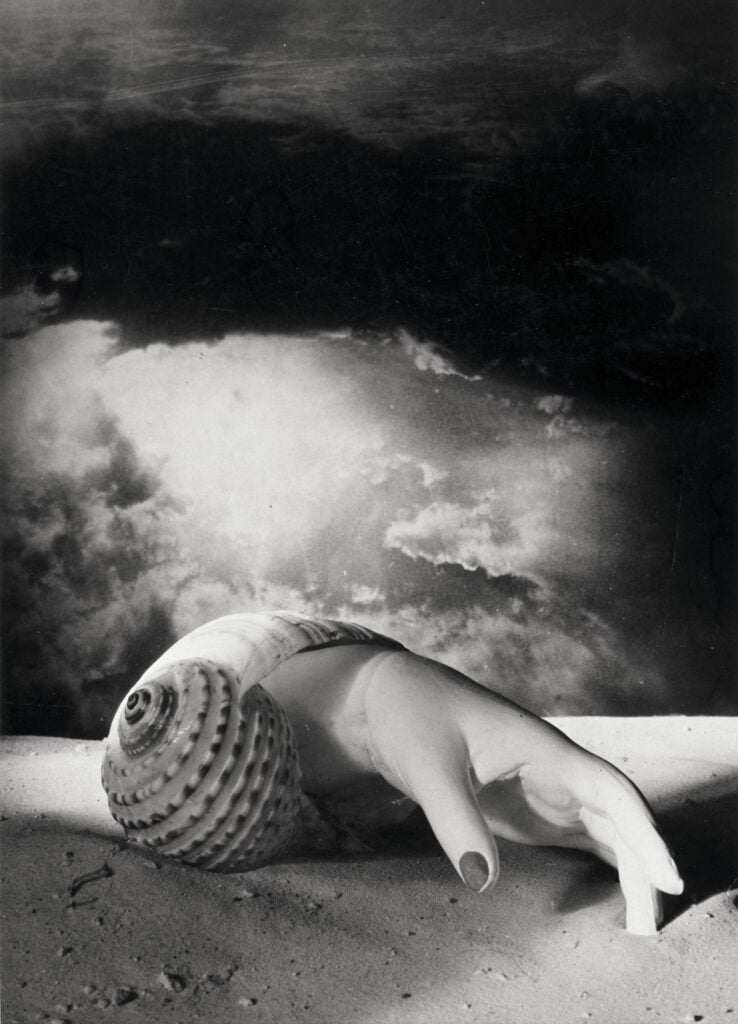

This autumn, from the Centre Pompidou to commercial art galleries, countless shows are celebrating the centenary of the Surrealist Manifesto. To mark the occasion, Numéro art invited two legends of photography, Luigi and Iango, to revisit the influential movement in an exclusive contemporary series. In parallel, the renowned art critic Philippe Dagen takes us through Surrealism’s fundamental principles, demonstrating that they have lost none of their pertinence today.

By Philippe Dagen.

The origins of Surrealism, a major artistic movement

So what is Surrealism? Looking back at its origins, one understands what it reacted against and what its revolutionary programme was; one also understands the reasons for its continuing significance today.

In Paris, in 1924, Surrealism was just a small group of poets in their 30s, most of whom came from Dada. One of them, André Breton, began a preface to Soluble Fish, a collection of his poems. While he wrote, the text started to take on a more general turn, transforming into a theoretical manifesto that included a dictionary-style definition of Surrealism: “Pure psychic automatism, by which one proposes to express, either verbally, in writing, or by any other manner, the real functioning of thought. Dictation of thought in the absence of all control exercised by reason, outside of all aesthetic and moral preoccupations.” The word itself was not new – Guillaume Apollinaire had coined it shortly before his death in 1918 – but Breton’s definition was novel and compelling.

A rejection of traditions and conscience

The first point: breaking away from traditions, discarding the authority of rationality and conscience. Automatism would allow the creative act to happen without its being subservient to any formal rules or “aesthetic and moral” laws. Everything within the person expressing him or herself could be laid bare, without self-censorship or taboos. Breton referred to what Sigmund Freud called the unconscious – during World War I he had trained as a psychiatrist, and was therefore familiar with the early works of the founder of psychoanalysis, who he went to meet in Vienna in 1921. The discussion didn’t go very far, but the essential point was the requirement for absolute freedom, which had only previously been achieved by a very few poets – Rimbaud, Lautréamont, and Jarry. This constituted a rupture with previously established principles and signified a declaration of revolution. Naturally, this call for untramelled liberty resonates strongly in today’s standardized, normalized, and ultra-monitored societies.

© Adagp, Paris, 2024.

From literature to painting, art in all its forms

The second point: this call is valid for all modes of expression, per Breton’s “by any other manner.” As a poet among poets – Paul Éluard, Philippe Soupault, Robert Desnos, Louis Aragon, etc. – he referred first and foremost to language. Indeed, initially, Surrealism was a literary avant-garde, and the title of the magazine that Breton had founded with Aragon and Soupault in 1919, and which he edited until its last issue in 1924, was Littérature.

Surrealism has remained a literary affair ever since – one of the movement’s leading poets, Annie Le Brun, died just this summer. To write a history of Surrealist literature would boil down to listing, in addition to those already mentioned, the majority of the most popular French-language poets of the 20th century, including Antonin Artaud, René Char, and Aimé Césaire. But, right from the beginning, Surrealism was open to any and all art forms.

Before it, Picasso and Apollinaire’s Cubism and Tzara and Picabia’s Dada had brought together writers and painters. But Surrealism turned this convergence of the arts into an existential principle. “The real functioning of thought” can take on the most diverse material forms, and the notion of automatism is as incompatible with conventional artistic teaching – an alienation of the creative self – as it is with technical specialization – a set of limits on that self. Therefore, there could be Surrealist visual arts, and Breton published the first edition of Surrealism and Painting in 1928.

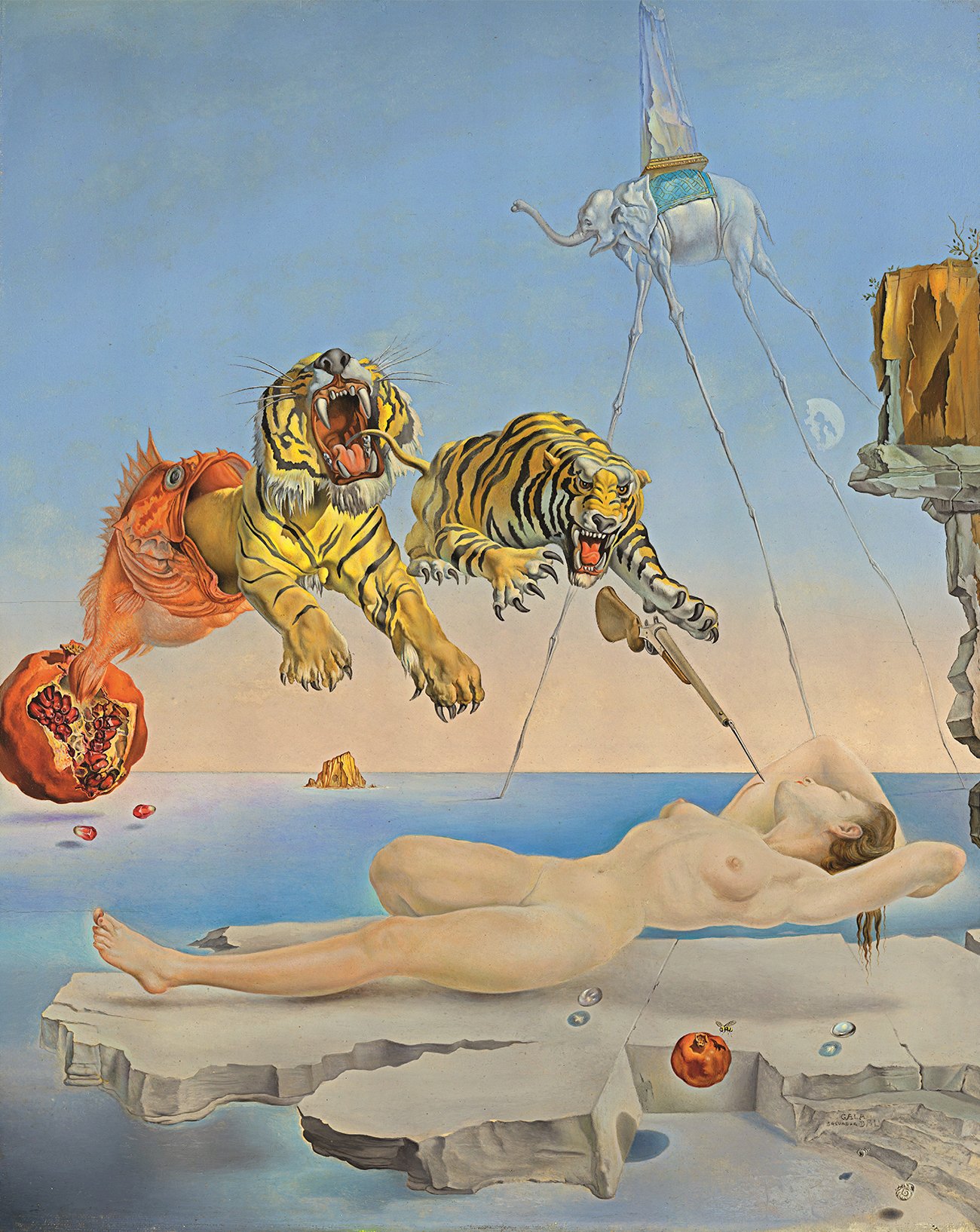

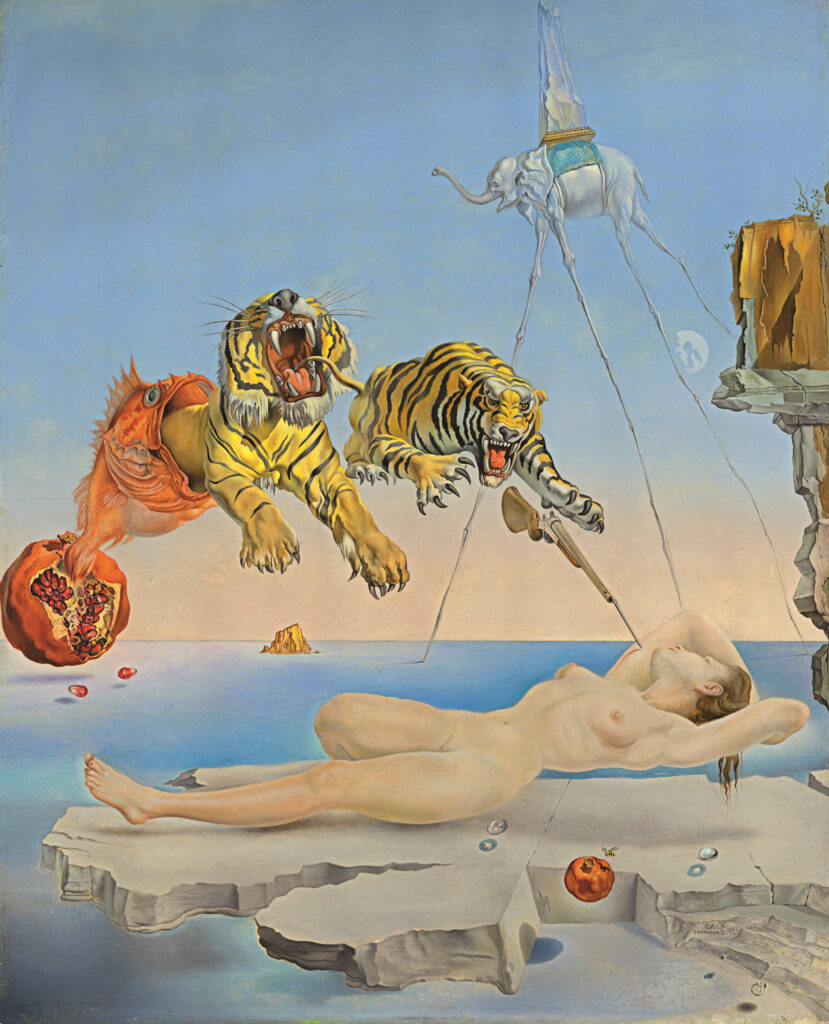

The principle was the same as in poetry: constant experimentation and a search for the unknown. Max Ernst, Joan Miró, Yves Tanguy, René Magritte, and countless others – so many that we shan’t even try to list them all – pioneered a whole new field of visual invention. Cinema went Surrealist too – Luis Buñuel, Alain Robbe-Grillet, and David Lynch, among others. Mulholland Drive is a Surrealist film in the truest sense of the word. So the point has been made: Surrealism revolutionized the arts.

The political and social commitment of the Surrealists

But that’s not all. The recognition that museums now grant the movement should not obscure a third, equally essential point. The Surrealists were not only revolutionary in their books and paintings, they were socially and politically revolutionary. The first magazine they created was called La Révolution surréaliste (The Surrealist Revolution), and was followed by Le Surréalisme au service de la révolution (Surrealism in the Service of the Revolution), an even more explicit title. Its pages featured dreams and also manifestos against the three repressive powers that were the army, universities, and psychiatric institutions. In its pages, Benjamin Péret derided Christianity while Éluard denounced European colonialism and Breton called for a general strike.

The Surrealists tried to form an alliance with the French Communist Party, but failed due to hostility from Moscow. As of 1936, with the unfortunate exception of Dalí, they all sided with the Spanish Republic against Franco’s coup d’état and joined the war against fascism. In 1938, Breton travelled to Mexico City to meet Leon Trotsky, and together they wrote a Manifesto for an Independent Revolutionary Art.

After France’s defeat in 1940, the Surrealists had to choose between exile – Breton, Péret, Masson, and Ernst among others, who fled to the US or Mexico – or joining the clandestine activities of the Resistance – Aragon, Éluard, Char, Bellmer, etc. In 1941, in Martinique, Breton discovered Césaire’s Journal of a Homecoming and became friends with the poet and his wife, the author Suzanne Césaire. Here again, it would be easy to find evidence to demonstrate that the Surrealist revolution sought to impact society as a whole – the growing moral permissiveness during de Gaulle’s presidency and after May 1968 was one of the results. It is therefore no surprise, at a time when puritanical regression and a renewed moral order are gaining strength, that the freedom advocated by Surrealism is once again a model.

The are two other equally topical reasons for this. The first is that Surrealism is incompatible with nationalism, aggressive patriotism, and, that fatal consquence of the two, racism. Ernst, who had been a German soldier and therefore an enemy, entered France in 1922 on Éluard’s passport – this is more than just a trivial detail. Two years earlier, the Romanian poet Tristan Tzara arrived in Paris from Zurich, where he had been one of the founders of Dada, like Victor Brauner, who later fled anti-Semitism. Miró was Catalan, as was Antoni Tàpies.

Surrealism, an international movement

The movement continued to expand between the wars, to Brussels, Prague, London, and the Nordic countries, as well as to Brazil, Mexico, the United States, and Japan. The Surrealist exhibitions organized by Breton and Duchamp in Paris in 1938, 1947, and 1959 all included the word “international” in their titles, and each welcomed newcomers. For example, the third exhibition featured works by Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns, who were unknown in Europe at the time. Surrealism greatly contributed to the internationalization of the creative arts in the disastrous context of the interwar period, which is another aspect that resonates today.

The same can be said of a final characteristic of Surrealism, namely the importance of female artists to the movement, which is much more readily acknowledged today than it was in the past. Toyen, Leonora Carrington, Remedios Varo, Dorothea Tanning, Jane Graverol, Ithell Colquhoun, and Louise Bourgeois were not the “wives of” or “models of,” but artists in their own right whose work now commands as much attention as that of their male counterparts. In 2022, the Venice Biennale displayed them together in a large – albeit not large enough – gallery so that everyone would finally get it. Since then, the initiative has gathered momentum; this is another example of Surrealism’s relevance for today.

“Surrealism”, exhibition until January 13, 2025 at the Centre Pompidou, Paris 4th.