19

19

Artist Michael Armitage speaks with Hans Ulrich Obrist on his love for painting and for Goya

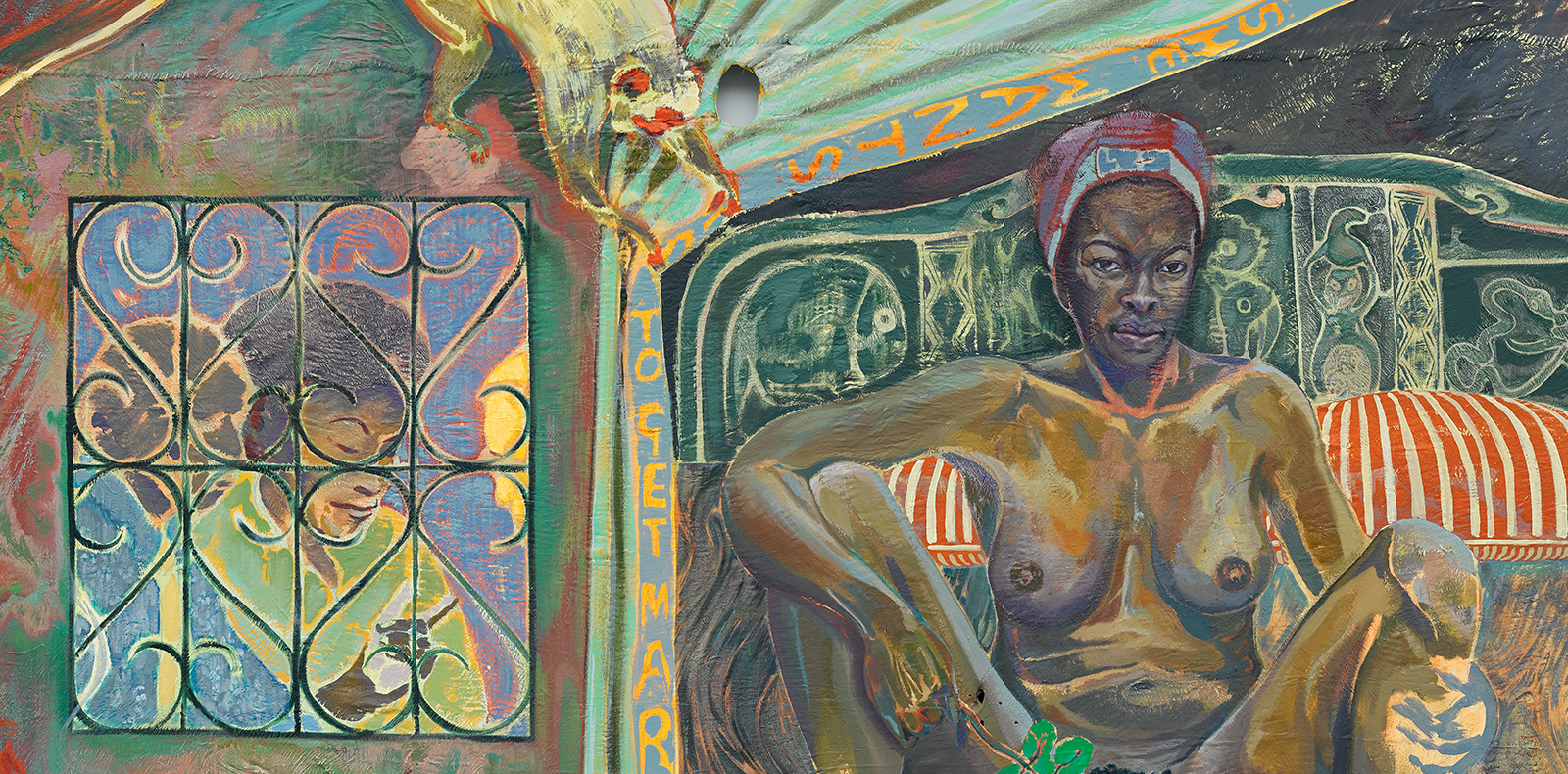

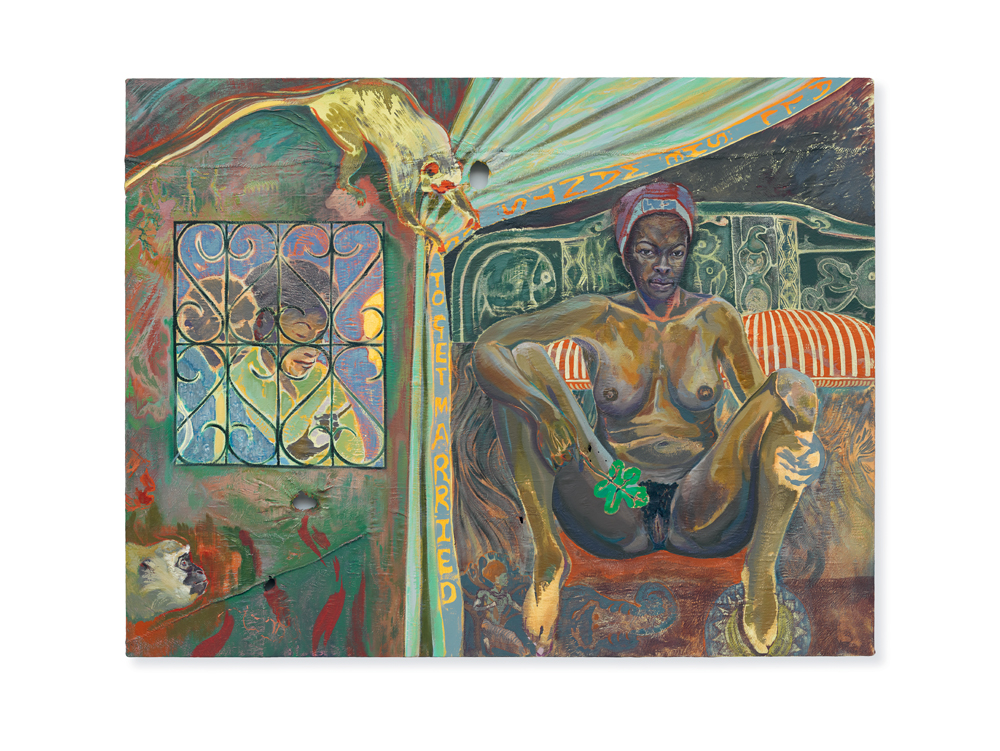

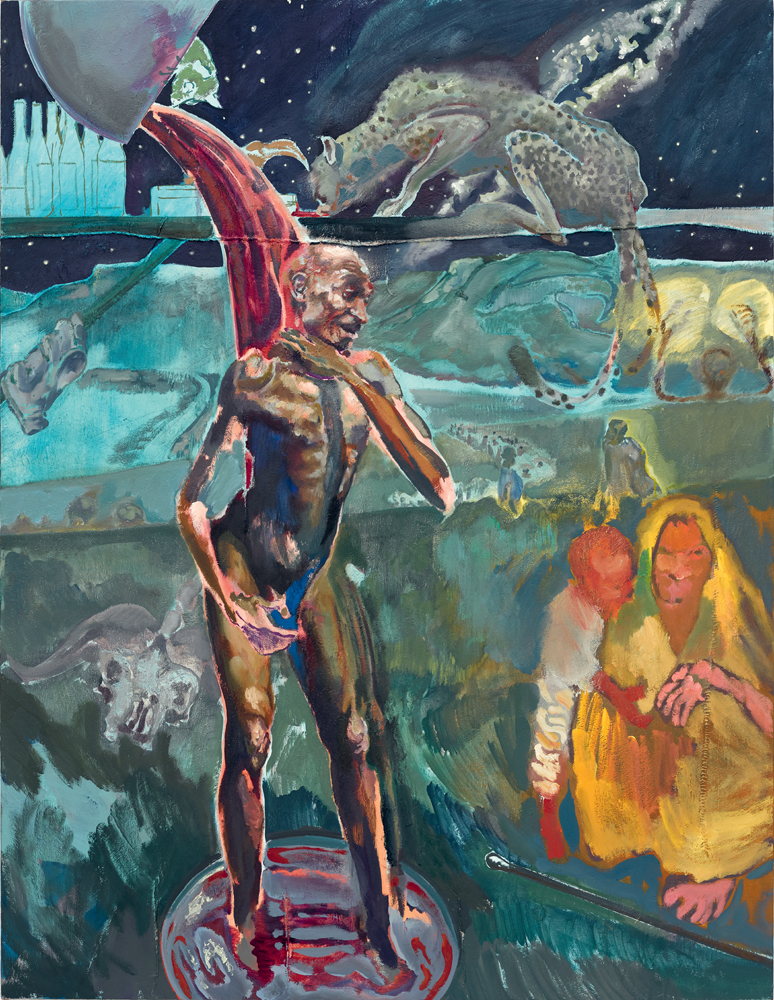

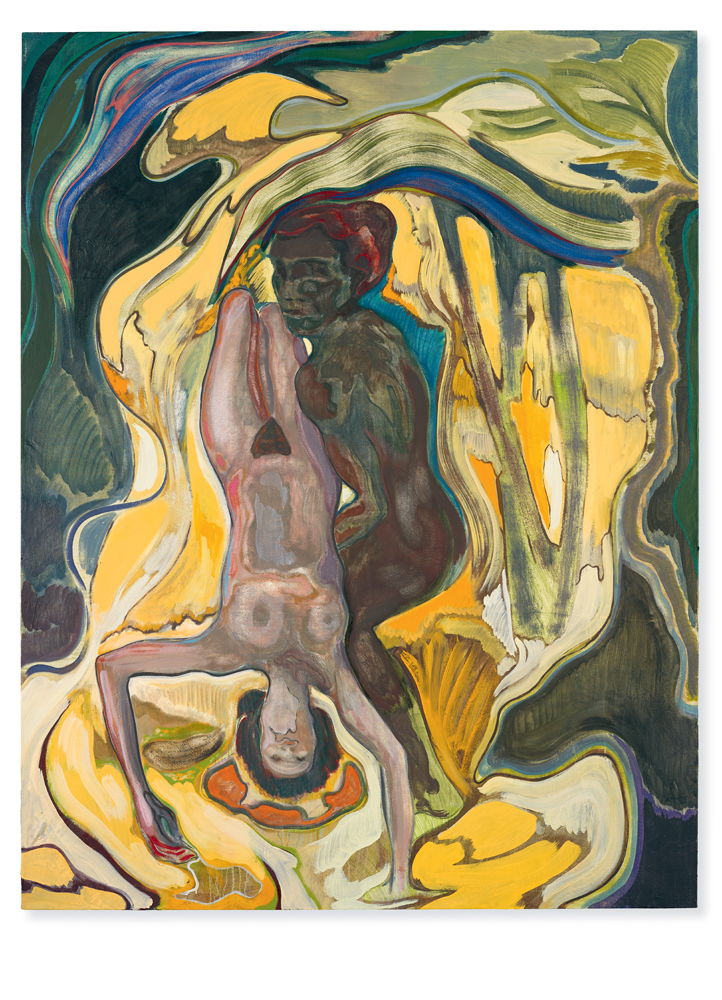

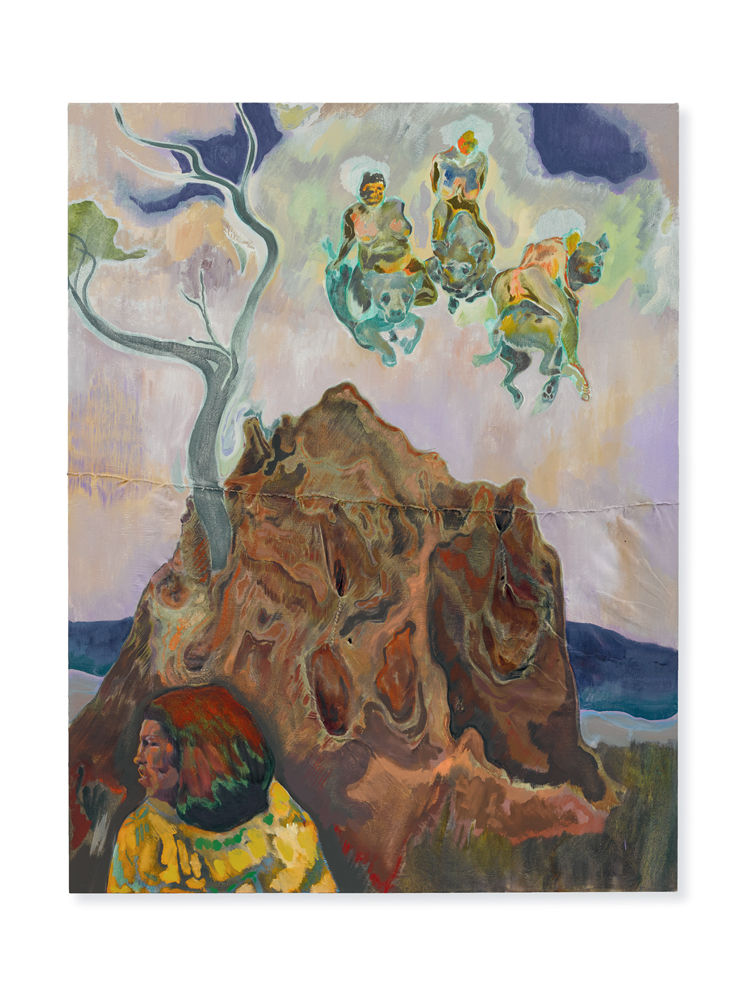

His complex canvases, with their rich colour palette and sophisticated blend of East-African and Western imagery, continue to fascinate. Until September 4th, Basel’s Kunsthalle is honouring the 38-year-old anglo-kenyan painter with a solo show, hot on the heels of Madrid, where his paintings dialogued with work by one of his ultimate references, Goya. He spoke to super-curator Hans Ulrich Obrist.

Interview by Hans Ulrich Obrist.

Hans Ulrich Obrist: How did you come to art, or, if you prefer, how did art come to you?

Michael Armitage: I started when I was about six years old. Like many kids, I drew a jet plane… [Laughs.] From there, I started making comics, that sort of thing. At nine or ten, I had a great art teacher who took me under his wing. I spent many weekends with him. He introduced me to oil painting, which was quite unusual for my age. He also introduced me to engraving and drawing. Art soon became central to my life, and still is.

Art history – references to Goya, of course, but also to Manet and Gauguin – plays an essential role in your work. Could you also tell us about the Kenyan artists who’ve inspired you? You included some of them in your recent exhibition at London’s Royal Academy of Arts, for example Chelenge Van Rampelberg, the extraordinary sculptor who was a big influence on you.

She was my gateway to the art world. Not just with respect to practice, but also on a private, personal level. Chelenge was the first artist I really knew – she was the mother of my best friend when I was a kid. She and her husband Marc, a furniture designer, had an extraordinary art collection, mostly from the 80s and 90s, but some older pieces as well. Their house had art on every wall, and it was probably the only place in Nairobi where you could see so much art all at once. Chelenge allowed me to see what it’s like to be an artist, simply by letting me spend hours and hours with her in the studio. She’s extremely patient! I remember one painting in particular, No Erotic Them Say by Meek Gichugu. It depicted a strange sexual amalgam of a zebra and a woman. At first I found it repulsive, but, as I looked at it over and over again, it became embedded in my imagination. The first time I saw it was in many ways similar to how I felt the day I walked into the Prado and discovered Goya’s Black Paintings. It was such an affront to the world. Everything I’d ever been told, the taboos, the things you couldn’t talk about in society, were all in those paintings. It was very raw.

Which brings us to Goya and your Madrid exhibition, which I curated for the Fondazione Sandretto Re Rebaudengo at the Calcografía Nacional, where your paintings and drawings dialogue with works by him. At the opening, you told the Financial Times that for you Goya is “a haunting presence … both in terms of what he does with an image technically but also from a conceptual point of view, the ideas behind what he chooses to paint and the way he reflects on society.”

My first encounter with Goya was a bit surreal. I’d been told about him by a professor when I was at the Slade School of Fine Art, but in a class on Gary Hume and his very minimal Door paintings. So when he referred to Goya’s Black Paintings, I immediately thought of the minimalism of a black square, a bit like Malevich. But when I went to the Prado for the first time, I was stunned to discover what they were really about: some of the most experimental, sophisticated, raw and extraordinarily powerful paintings you could imagine. Once you’ve seen Goya, nothing is ever the same, especially for someone who thinks about painting, about how to paint, about subjects, about what happens to a canvas when you paint a subject in that space, about an artist’s responsibility to his or her own culture or society.

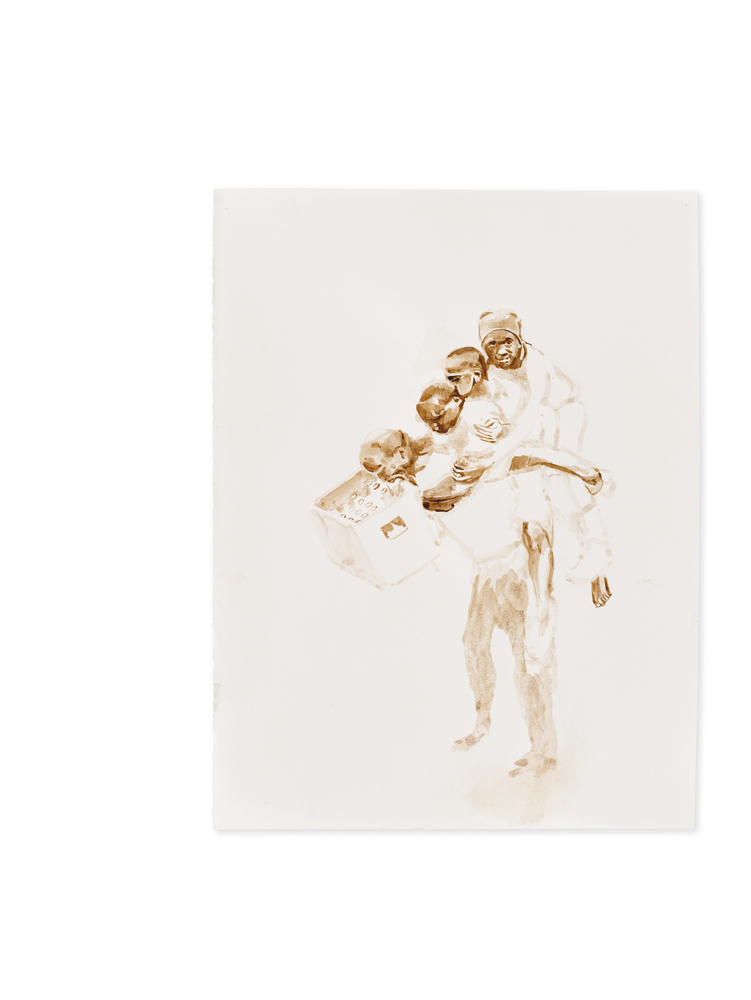

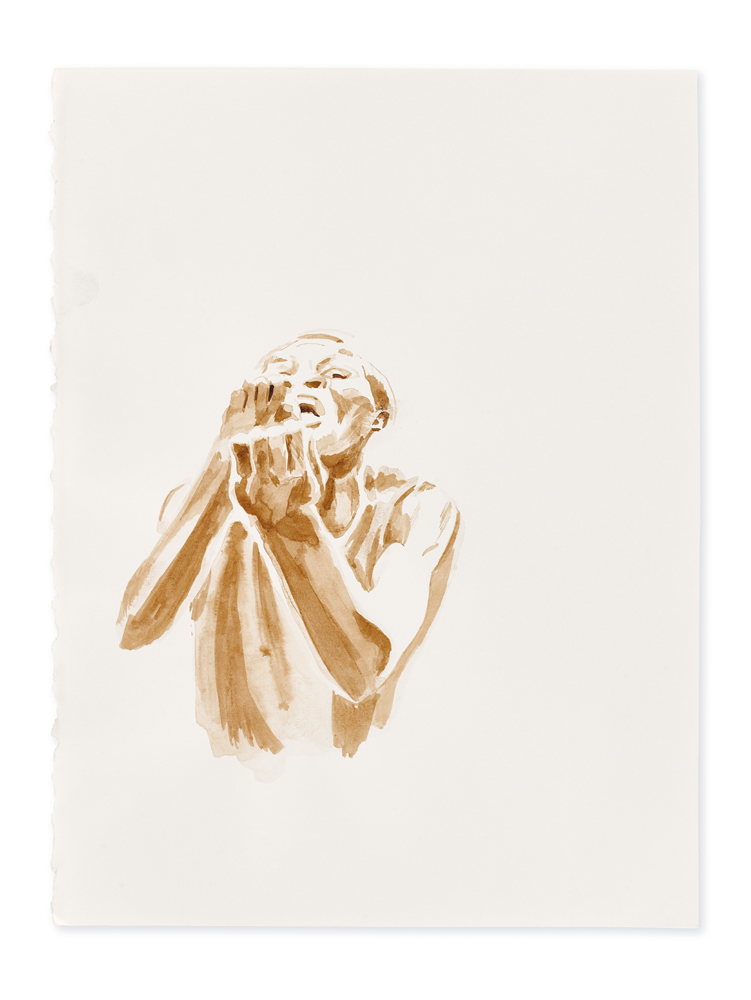

Drawing is particularly important for you. You told me earlier that Goya’s drawings might appear fast, but in reality they’re slow, and that it’s never about the line…

I’ve always felt that his drawings were done quickly. Not effortlessly, mind you, but they give an impression of speed. If you look at them closely, you see that the fold of a mouth, for example, is not made up of a single line, even though that’s the impression it gives. In reality, it’s made up of seven or eight different lines, starting with something very delicate, then building up, adding gradually, over and over again. This very delicate accumulation of lines creates an illusion of motion – you think the drawing is vibrating. Sometimes he uses a brush that’s not loaded with enough paint, which produces these terrible dry scratches on the surface.

Drawing is particularly important for you. You told me earlier that Goya’s drawings might appear fast, but in reality they’re slow, and that it’s never about the line…

I’ve always felt that his drawings were done quickly. Not effortlessly, mind you, but they give an impression of speed. If you look at them closely, you see that the fold of a mouth, for example, is not made up of a single line, even though that’s the impression it gives. In reality, it’s made up of seven or eight different lines, starting with something very delicate, then building up, adding gradually, over and over again. This very delicate accumulation of lines creates an illusion of motion – you think the drawing is vibrating. Sometimes he uses a brush that’s not loaded with enough paint, which produces these terrible dry scratches on the surface.

I’d like to know more about your series of paintings that was inspired by the Kenyan presidential elections, which you realized between 2017 and 2019. For your research, as well as collecting photographs, you at- tended election rallies. One of the paintings you showed in Madrid is called Mkokoteni, a Swahili term for the kind of handcart depicted in the painting…

When I started working on the series, I wanted to think about the relationship between a leader and those who follow him, and what each person might have to gain or lose in that relationship. So I wasn’t – and I’m still not – interested in politics per se. But when I went to the rally, all my preconceptions were swept away. The reality was way more captivating. For me, it wasn’t important that it was an opposition rally, what interested me was the behaviour of those present, what they were willing to give of themselves – some of them would have laid down their lives. There was a performance dimension to it, which was perhaps the real key to the event. The supporters were dressed outrageously, in massive orange wigs – it was fantastic! I don’t know what kind of politician thinks dressing up their supporters as clowns is a good idea. One guy was holding up a reproduction of Leonardo da Vinci’s The Last Supper, but with the politician’s head floating above Jesus – higher than him. And the candidate’s speech was all, “I will take you to the Promised Land! I’ll bring you to the land of Canaan!” He was dressed entirely in white. Many of those present were paid by the politician to take part and raise the energy. And if you look at photos of rallies that turned violent, you’ll see the very same guys, usually the most outrageously dressed, throwing stones and engaging with the police. It made me think: if the rally turned really violent, and one of these guys hired to be part of the mob were hurt, he’d become some sort of dubious martyr for the cause. While at the rally, I was interviewed for the radio, so I had to describe the scene. As I did so, I realized I was literally describing a Goya print. [Laughs.] It felt like a living version of a Goya scene, and also recalled an aspect that he mastered in his work: the great depth and humanity he manages to include, which creates an immediate connection with people.

You mentioned the complexity of the situation, and this sort of complexity is something you recreate with brio in your paintings. In your work, you bring all these worlds together in the composition, with forms and images that are “cut out” and “pasted” in many different ways. Suddenly, it all falls miraculously into place.

I’d find it hard to say that everything falls into place, because I generally feel there’s a certain disparity. This is why I also have a problem talking about subject matter or that kind of thing, because if you take all the reasons why you strive to make a painting, the subject is no more important than the materials, which are no more important than the technique, and so on. The subject also evolves over the course of painting the work, even if there are certain aspects that I tell myself at the start are going to be the centre of focus. But very soon the painting starts to demand certain things, and you have to obey it, because otherwise you’ll end up with an illustration rather than a painting.

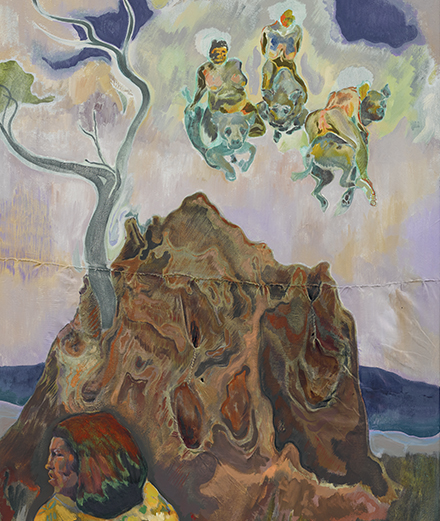

Etel Adnan once told me – she was 96 at the time, and passed away the following year – that her best friend throughout her long life had been a mountain in northern California called Mount Tamalpais. This connection with the natural landscape is something that’s very important in your work too. For example, in your painting Mangroves Dip, there’s a tree that suddenly becomes a protagonist in its own right.

Yes, I’ve really thought a lot about natural landscapes, about how they can be used in painting. When you discover a place as an outsider, and you include that landscape and bring it into your work, something happens – it’s an extremely objective inclusion, which has a very romantic, even sublime side to it. You will appreciate the expanse of the sky, the height of the tree. But, when you have a work showing a landscape that the artist actually lived in, then the landscape generally becomes much more abstract. It’s as if the natural setting becomes another character, and not simply a decorative backdrop.

Michael Armitage, “You, Who Are Still Alive” until September 4th at the Kunsthalle Basel.