2

2

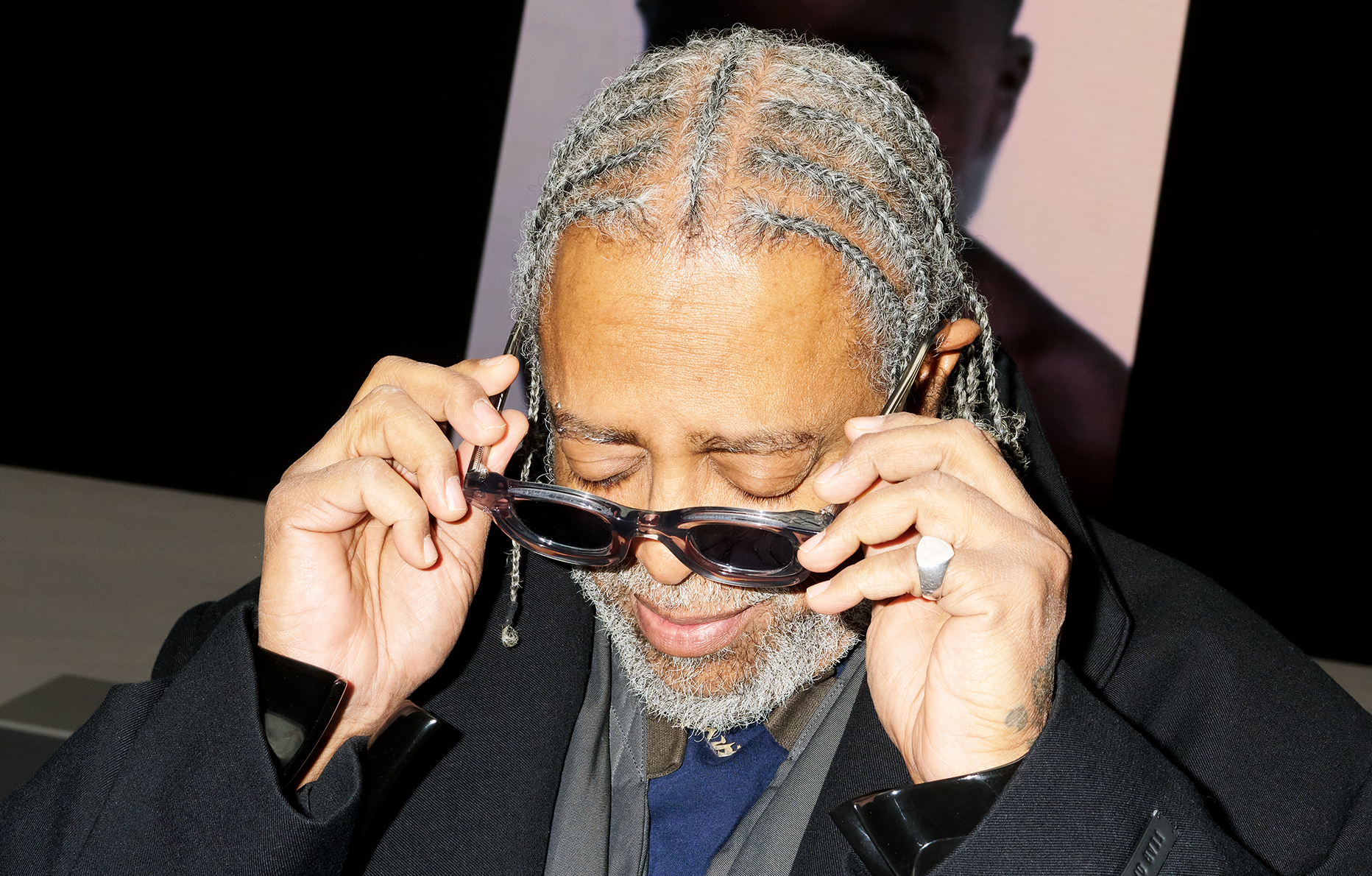

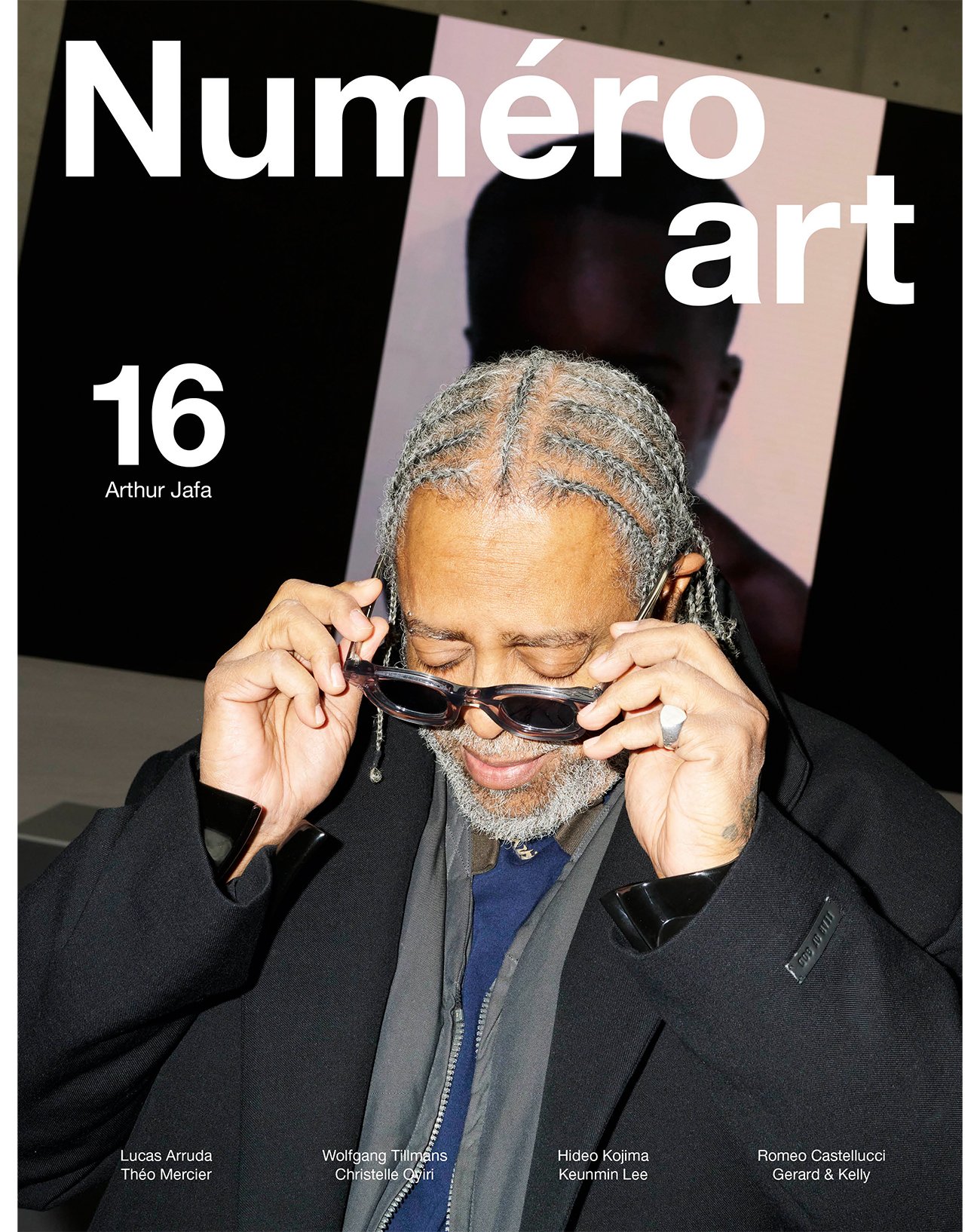

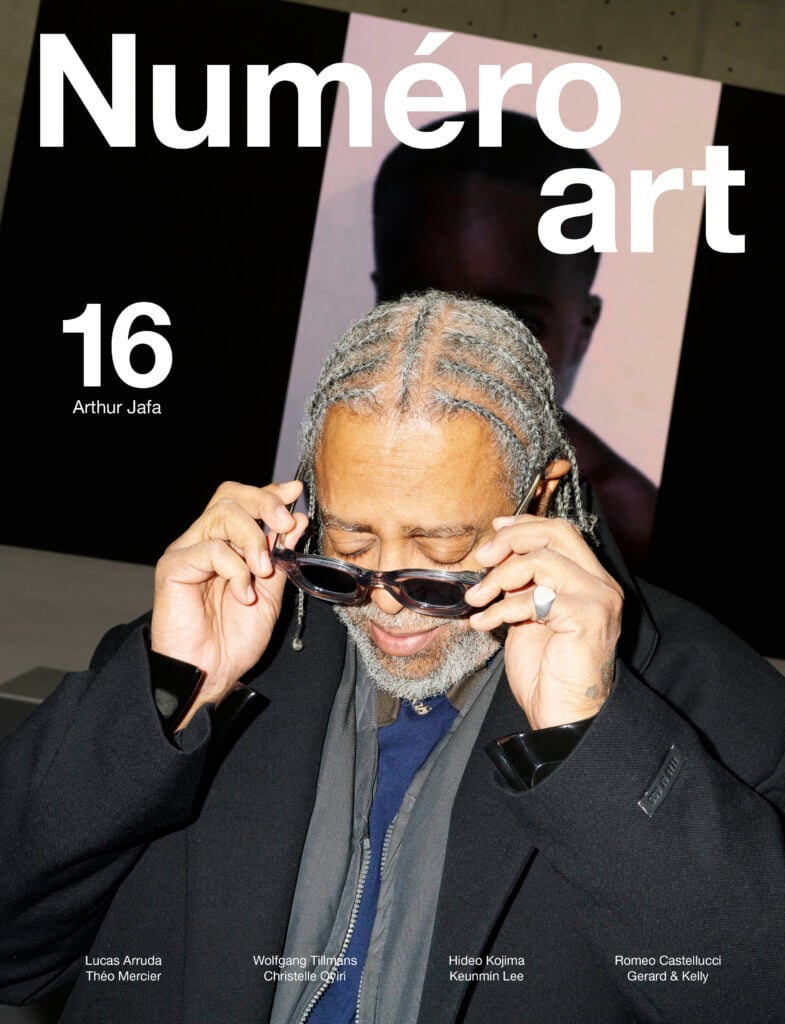

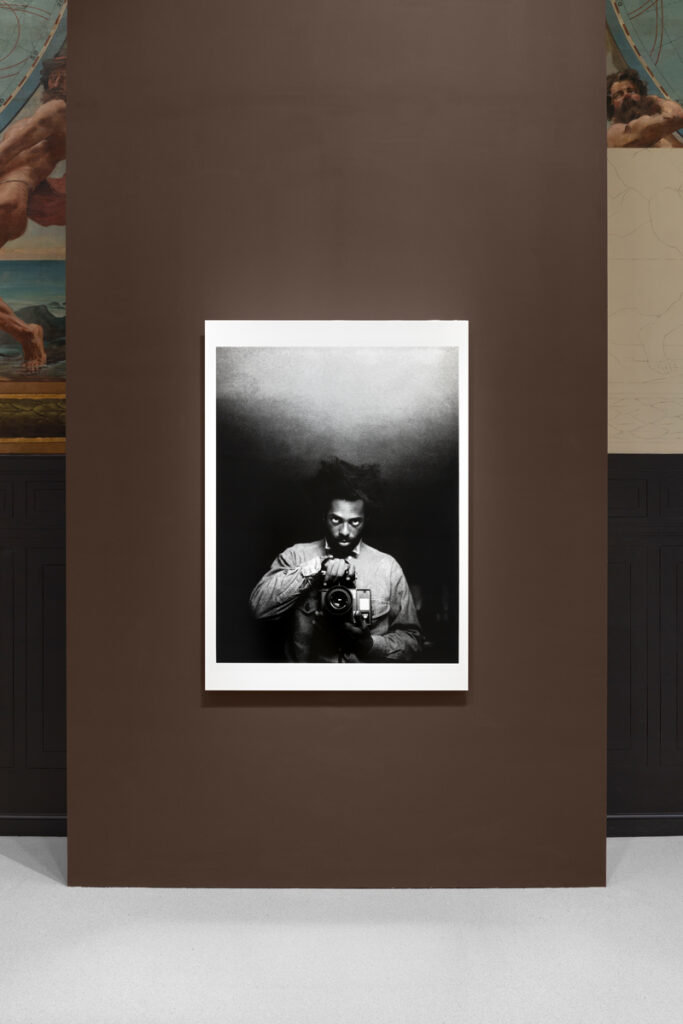

Interview with Arthur Jafa, legend of contemporary art celebrated at Bourse de Commerce

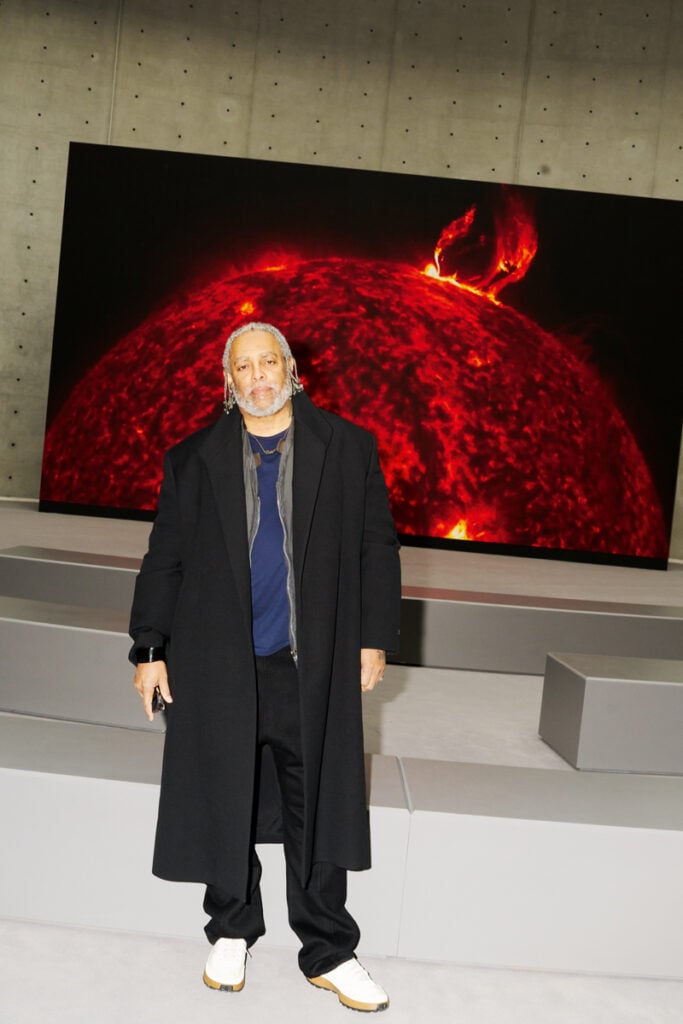

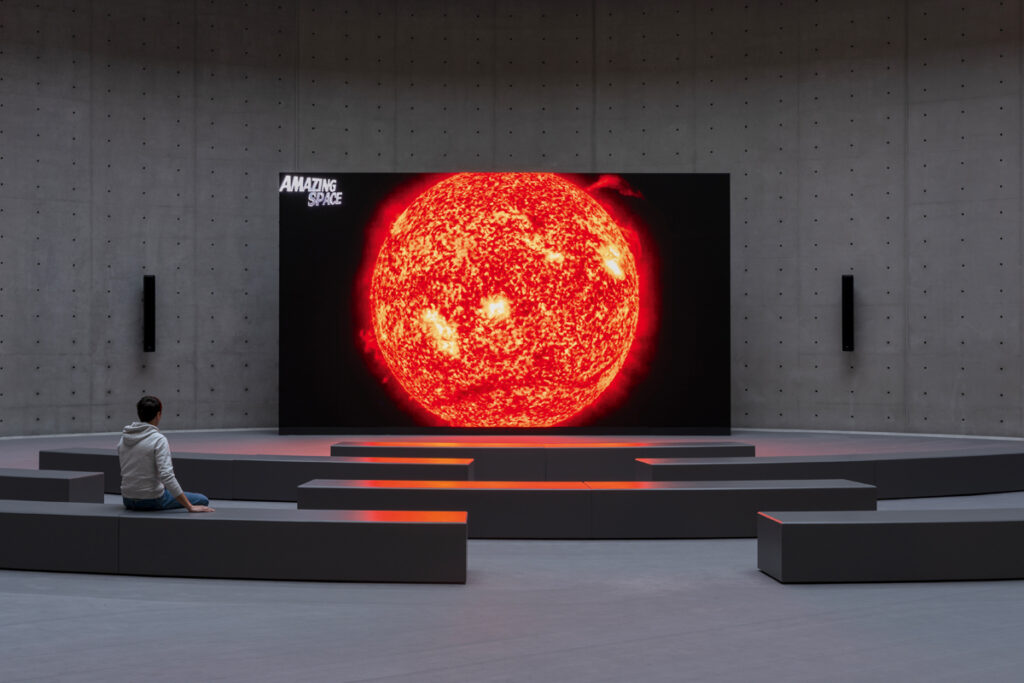

The legend of contemporary art Arthur Jafa, on the digital cover of Numéro Art, is currently at the centre of the exhibition “Corps et âmes” at the Bourse de Commerce. The Los Angeles-based photographer and video artist is displaying three of his best films, among them the acclaimed Love is the Message, the Message is Death (2016), a vibrant homage to African-American culture that is showing in the rotunda. Interview.

Portraits by Katja Rahlwes,

Interview by Cyrus Goberville.

Published on 2 May 2025. Updated on 4 July 2025.

Cyrus Goberville: Black music has always played a key role in your work. You featured techno legend Robert Hood in your 2013 APEX, Kanye West’s Ultralight Beam in the 2016 Love is The Message, the Message is Death, Future’s Mask Off in The White Album in 2018, Al Green that same year in akingdoncomethas, and a transposed version of the R&B band Rose Royce in your 2021 film AGHDRA. How would you define “Black music”? Arthur Jafa: I think it’s a result of the confrontation of African ways of seeing the world with the Western understanding of time and space. Black music was the dominant cultural form of the 20th century. If you look at the reach of Black music, it’s not just Black folks who like Black music – that’s the thing. Black music is a product of the West. If you look at traditional African music, which is incredibly diverse, you can’t reduce it to one thing.

When you say “Black music”, everybody understands that it grew out of or evolved from traditional African music. But at the same time, I could mention 1,000 things that don’t sound like anything you ever heard in traditional African music. Even when you say Black music, would you ever confuse Billie Holiday with Jimi Hendrix, or Jimi Hendrix with John Coltrane, or John Coltrane with Jay-Z? There are a zillion things that fit under this umbrella we call Black music. So trying to understand Black music is just another form of trying to understand Blackness. Because it is not the only, but certainly the most prominent, expression of Black people’s existential experiences in the West.

How would you describe the complex relationship between your work and music? Sometimes I have a slightly ambivalent relationship to music in my work, because it feels like the music is so powerful. It’s almost like you could just put the music over anything and it would be interesting, literally. When you find an artifact and don’t know how old the artifact is, they do carbon dating. I almost feel that putting the music alongside visual stuff is a weird kind of carbon dating. I hate to use the word “authenticity,” but the power and the depth of what’s happening in the visual thing is marked by how that music is tracked alongside it. That happened with akingdoncomethas, because, at a certain point early on, I was like, “Oh, you think this art stuff is doing something? Let me show you what doing something really looks like. It looks like Le’Andria Johnson, it looks like Al Green.”

“There’s no contemporary pop music that’s not Black. It’s just all Black music at this point.” – Arthur Jafa.

Those are my metrics. I mean, I love Bruce Nauman and Marcel Duchamp. There are so many artists I love, but at the end of the day, do I love them the way I love Al Green? No, not really. I can lie to other people, but I don’t lie to myself. If I look at my work, I say, “Is my work actually doing this?” And 99% of the time, it’s not. But it’s what I aspire to.

On some level, Love is the Message, the Message is Death just tapped it. But I feel like I’m constantly trying to make things that wouldn’t pale next to almost any Black music. And when I say any Black music, I mean everything from Kanye to Bob Dylan. You know what I mean? There’s no contemporary pop music that’s not Black. It’s just all Black music at this point. There’s all this incredible music in the world, but when you talk about pop music, you’re talking about Black music, whether it’s techno, reggae, or whatever.

You worked with Stanley Kubrick on his last movie Eyes Wide Shut (1999). Was the use of music in your work in any way influenced by Kubrick’s soundtracks? The monolith scene in 2001: A Space Odyssey is maybe the earliest instance I can think of where a filmmaker used classical music to accompany images. It’s a great archive of the difference between sound and image. There’s always a satirical edge with Kubrick: the music is outside of the image you’re looking at. In his films, like A Clockwork Orange, or even Barry Lyndon, where the music is period accurate, the way the soundtrack works in relationship to the narrative is super sarcastic.

That’s also true of Full Metal Jacket, where in a very strange way you can’t remember the music at all – the only thing I remember is the soldiers singing, and when they sing Mickey Mouse, I know there must be music in it, but it almost feels like Robert Bresson, where music is absent.

Just like the scene at the train-station in Lyon in Bresson’s film Pickpocket (1959), entirely cadenced by footsteps. That’s all you’re hearing. You just hear the small details that make it work. It’s funny, I’m more identifying myself with Bresson, even though in my videos I use music in a very emotional way, to create an atmosphere. I don’t like this in cinema so much – that whole idea of music telling you how to think from moment to moment.

Kubrick doesn’t do that. His use of music is really different, almost an authorial realm to cast what you see in a certain light. With him it’s very rare to see the music underlining the character’s emotions in any literal way. Versus, say, Scorsese, who uses music in a much more embedded way – if you think of Mean Streets or Taxi Driver, you feel the music is atmospheric more than anything.

Talking of Taxi Driver (1976), you showed the ambitious ***** in 2024. This work is remake of one of the final scenes in Scorsese’s movie, where Travis Bickle [played by Robert De Niro] shoots people in an East Village brothel to save Iris [Jodie Foster]. You told me once that Bernard Hermann’s soaring, saxophone-led score echoed John Coltrane’s Naima (1959) so closely it could have been directly lifted from it. When I was working on *****, I didn’t really think about that so much, because the parts I’m looking at don’t use that music, which is primarily heard when Travis Bickle is driving the car. In *****, it’s mainly just him pulling up, going in, and doing the shooting. But to me, it was all part of how insidious and complicated the relationship with Black people is in this movie. You take John Coltrane and you take him out in a way – you make him disappear.

“Records are time machines.” – Arthur Jafa.

On a similar note, in the original movie, the pimp Sport, played by Harvey Keitel, is white. When you discovered that the film’s screenwriter, Paul Schrader, had intended Sport to be African American, you decided to “restore” the movie by introducing Black actors, except for Robert De Niro and Jodie Foster. They switched the colors. I’ve definitely had friends of mine, Black folks, be like, “Why would you want to make the film so the right people are getting killed?” My reply is that, first of all, I was just trying to make the film be true to itself and not be this confusing or contradictory artifact – to make it an artifact that says what it believes, even if that’s fucked up. You can see it for what it is, as opposed to being subjected to these strategies that are basically about destabilizing your understanding of what you’re looking at.

This intervention has a French word: détournement. The thing I tried to do was really about correcting it, or taking parts out so you can reveal what it truly is. One person said, “Oh, it’s like Dylann Roof” [the white-supremacist who, in 2015, carried out a mass killing in a Black church in Charleston]. But it was always like Dylann Roof! It just got complicated because in the end Travis Bickle goes into a white church.

I’ve been obsessed with Stevie Wonder records since I saw ******! Why did you use his song As, which is so joyful, when the pimp is filmed in the street just before something so dramatic is going to happen? In 1976, everybody was listening to Stevie Wonder’s album Songs in the Key of Life. I remember that period well – it was all my family listed to for two whole years, it dominated everything at home! At the end of the day, I think that the song that feels most emblematic of the whole record is As. It’s pretty apocalyptic in the biblical sense. Using it in ***** was just a way to say, “Hey, look, this pimp, you suppose you know what’s going on in his head, but you don’t know what’s going on in the Black people’s heads.” It’s also period accurate, because both Taxi Driver and Songs in the Key of Life were released in 1976, even though he had been recording it for several years before.

Do you listen to new music? I’m curious about anything. For years, I’ve been interested in Future. Like somebody said, he may not be the biggest rapper, but he’s more influential than Jay-Z.

You once mentioned that you enjoy Dean Blunt’s music. I had coffee with him four years ago at exactly this same table we’re sitting at, and we had a long discussion about David Hammons and rage in hip-hop. The whole trap genre, it’s all about depression, it’s just rage turning inward. It’s not like Public Enemy, which was rage turned out, you know what I mean?

I always remember where I bought my records. Do you? Oh, yeah, totally. Records are time machines.

Do you still own a lot of records? Yes. There are some I haven’t listed to for 30 years, because I want to write about that period in my life, and I know that if I keep them aside, when I play them they’ll take me right back there. If you play the same music every day, you lose that.

There’s this one record by Stevie Wonder called Fulfillingness’ First Finale. My dad played it every morning before we went to school. So I don’t want to listen to it until I’m ready to write about that period in my life. I’ve been literally avoiding it, though I’ve heard it once or twice by accident. I don’t want it to lose its power.

Arthur Jafa, exhibition open until August 25th, 2025, at the Bourse de commerce, Paris 1st.