5

5

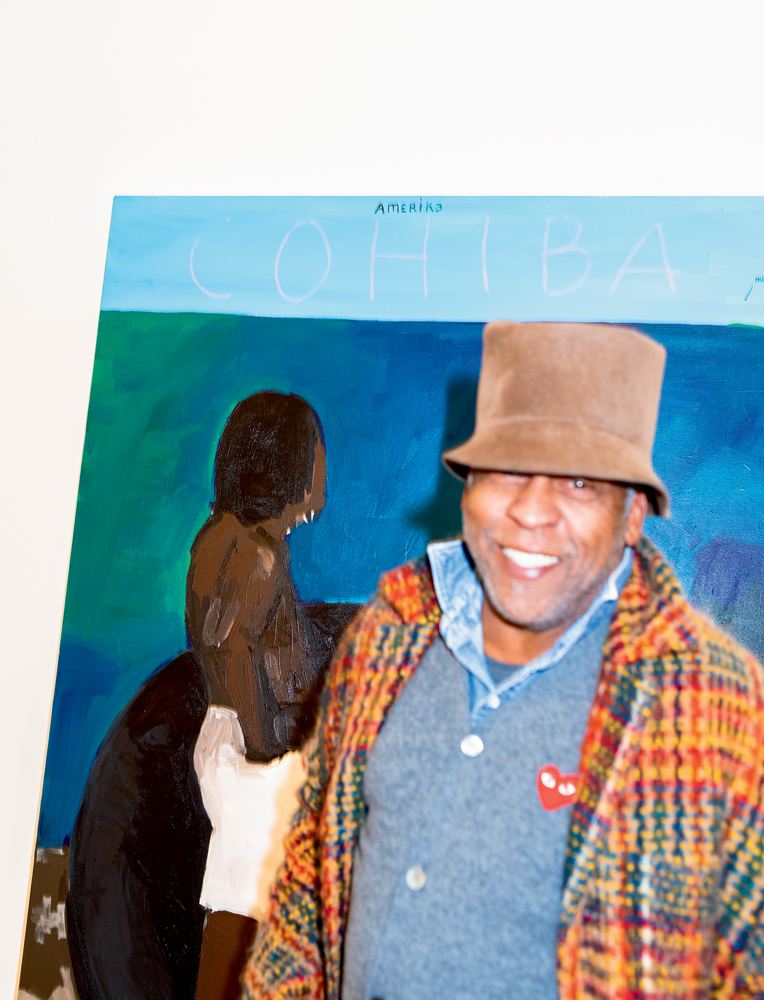

Meeting Henry Taylor, Afro-American legend of contemporary art

A fixture on the African-American scene, Henry Taylor spent his winter in a tiny Somerset village working on a new series for Hauser & Wirth. Numéro art caught up with the sharp, funny and exuberant 63-year-old.

Portraits by Maurits Sillem,

Interview by Charlotte Jansen,

Portraits by Maurits Sillem,

Interview by Charlotte Jansen.

Henry Taylor’s reputation as an artist is almost eclipsed by his rambunctious persona – even via Zoom, his energy is immediate and boundless and the conversation bounces to unexpected places and is punctuated by song. Born in Ventura, California in 1958, he grew up in nearby Oxnard; though he always had a certain predilection for painting, he only pursued it as a profession later in life. After taking art classes in Oxnard, with the legendary James Jarvaise, he went on to complete a BFA at the California Institute of the Arts, graduating in 1995 – until that point, he had been working as a psychiatric nurse at Camarillo State Mental Hospital.

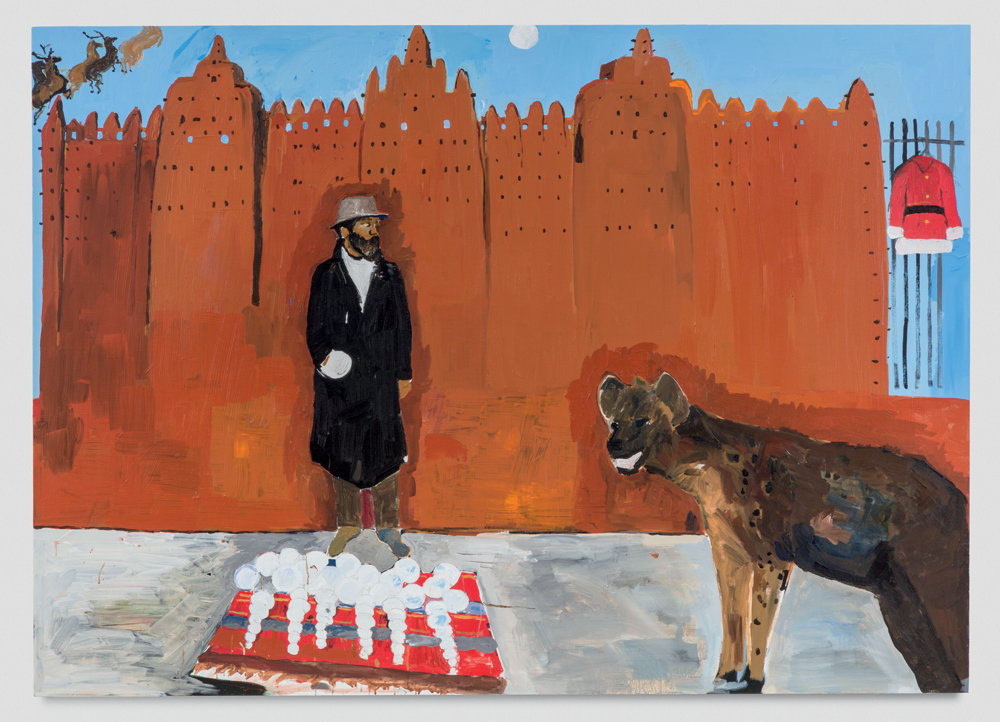

Taylor is an exceptional portraitist: his fluidity and panache as a painter and sculptor are like no one else working in the US today. He riffs off almost anything you can imagine, incorporating everything and everyone from a racist bumper sticker his brother once saw and told him about to trash thrown in the street, his family, his friend Emory, or Jay-Z and Obama. He freely mixes fact and fiction, memory and story, movement and emotion, and there is no hierarchy between any of these things because Taylor inhabits a higher plane. His insatiable curiosity about people and life is perhaps one of the reasons his work is so special.

His insatiable curiosity about people and life is perhaps one of the reasons his work is so special.

At the time of our interview, it’s the thick of winter and the middle of another lockdown, and Taylor has flown from California to the tiny village of Bruton in Somerset, deep in the English countryside. It’s the last of several weeks he’s spent there on a residency, in preparation for his first major solo exhibition in Europe at Hauser & Wirth Somerset, run- ning until June this year – initially opened online, it includes his first ever outdoor sculpture. Taylor has exhibited consistently across the US since 1999, with his first institutional solo at the Studio Museum, Harlem, in 2007, and a mid-career survey at MoMA PS1 in 2012. In 2022, if all goes to plan, he’ll have major exhibitions at the Fabric Workshop and Museum and MOCA, in Los Angeles, the city that has defined him and that he has defined. His studio is just off Skid Row in downtown LA, and its residents and regulars frequently drift in and out to see him. Sometimes he makes them a meal, sometimes he paints them.

Numéro art: You’re the youngest of eight kids. Tell me about your siblings – I’ve heard that they’re extremely important to you.

Henry Taylor: I have a brother named Ardmore. I didn’t get to know him till much later in life. He’s 78, he was a professor, went to UCSB, he’s a Sagittarius, wild, wacky, crazy, super-cool, love him. [Bursts into song.] Then there’s William Gene, we call him Gene. He was military, he was drafted, he went to Vietnam, came back. He had his own little agenda you know… He said he invented the shag, the hairstyle. He got a doctorate in religion. He lives in Tennessee. Then, my brother Hershel Earl Taylor got shot in Vietnam at the age of 22. I read all of his letters to my mother continuously, so I felt like I had firsthand experience of the war. He died five or six years later in Germany be- cause there was shrapnel in his body and he had a heart attack. Once I was watching a Brad Pitt film and I thought about him all night. His grandson is a world-champion mo- tocross biker, which fucking blows my mind! Hershel was amazing. He wore cufflinks every day, even in high school. He was like that motherfucker from Harlem, Dapper Don. He was slick every day. One night at the MoMA PS1 dinner, I was sitting next to Jerry Speyer, who was wearing gold cufflinks, and I told him about my brother. Jerry Speyer gave me his cufflinks after that story. I didn’t know who Jerry Speyer was. Then there was my sister Anna Laura, who was a civil-service worker and who I loved dearly but who died of cancer. Then there’s Robert, who we call Randy: he’s really smart, a straight-A student. Johnie Ray was named after the singer and he was burned all over his body, and that had a profound effect on me. Then there’s my sister Evelyn, then there’s me. I’m Henry the Eighth I am!

Randy also gave you the idea for one of the main sculptures that’s displayed in your current show.

I made this sculpture here of a guy running with a leather jacket. [Bursts into song.] You see this sculpture? So one day my brother Randy said, “Henry! I saw a bumper sticker that read ‘I couldn’t find me no deer so I shot me a nigga.’” It was probably in Texas or somewhere. And I made this sculpture which is here now. Randy started a Black Panther chapter. That sculpture has a leather jacket on it, and for a minute there I wasn’t sure about the jacket, but then a lot of people said, “Hey, your brother had us wear leather jack- ets like Huey Newton.” What else do you want to know?

C’est Randy qui vous a donné l’idée de l’une des principales sculptures présentées dans cette exposition.

J’ai réalisé ici cette sculpture d’un type en train de courir, vêtu d’une longue veste en cuir. [Il se met à chanter.] Vous voyez ? Un jour, mon frère m’a parlé d’un autocollant qu’il avait vu sur une voiture et qui disait : “Je n’ai pas trouvé de cerf, alors j’ai abattu un Nègre.” Il avait dû voir ça au Texas, ou un truc dans le genre. Et moi, j’ai fait cette sculpture, qui maintenant est ici. Dans les années 60, Randy avait fondé une branche locale du mouvement Black Panthers. J’ai mis une veste en cuir à cette sculpture… au départ, j’ai hésité, mais pas mal de gens m’ont dit : “Tu sais, ton frère nous faisait porter des vestes en cuir, comme Huey P. Newton [le cofondateur des Black Panthers].” Que voulez-vous savoir d’autre?

“I’ve been a listener all my life – being the youngest you don’t always get to talk, so you observe.”

Well, you were the youngest, so were you always the cute one, the one that got all the attention?

You think I’m cute? Golden nugget, that was my nickname! I never thought I was cute. I always had this high forehead and people used to grab my head and shout, “NUGGET!” So honestly I never felt like that. But I was the youngest and you get to hang out with a lot of people. I got to hang out with my dad who was actually a painter, an industrial painter, and from an early age, five or six years old, I went to hang out with him and watch him paint. I was very close to my mom. My parents divorced and I lived with my dad when I was 19 and there’s things I know about him that my siblings don’t. He told me all kinds of things, like about the day my grandad got shot, when my dad was nine years old, and what he did. I felt very privileged, for lack of a better word. My mom would ask me to come wash her back, sitting nude in the bathtub. Everything was so fucking natural. My mom would tell me stories, like about where she got the scars on her knee. She talked about objects like scars. I met people on Skid Row who told me they were the first Rodney King riot-victims and showed me the scar on their head where they’d been beaten with a flashlight. It made me a listener, too. I’ve been a listener all my life – being the youngest you don’t always get to talk, so you observe.

Is that where the storytelling came in? Observation is so important when it comes to painting portraits…

I think I thought about painting when I was five years old, but I never did it. I was already seeing stories, I was peeping in and out. I wanted to be a writer, but I’m too angsty for that, it takes too much discipline.

How about your dad? You once made a film about him witnessing your grandfather getting shot when he was just a child.

My dad used to call his sons bullets. Where the fuck did that come from? It didn’t occur to me until 20 years later, when I was on a residency in Texas and they said I could make a film. What I’m saying is that a lot of shit doesn’t resonate right away – he called us bullets because his dad got shot, he got six boys, and there are six bullets in a re- volver. My dad was creative like that – I thought of him like a poet. I put words of his on the wall when I graduated from CalArts. He was challenging people all the time. Sometimes we don’t acknowledge people. On my birth certificate it says “Father’s occupation: painter.” Didn’t mean much to me. Then I said, “Damn, ain’t that a trip! Used to watch him paint. Walls, and shit. There’s something there.” You see your dad run, may not be sprinting, patterns. My dad did, my brother, who was a barber, cut faster than anyone, so speed became a big factor in my painting. I always wanted to paint fast. I’d think about him.

You’re known both for your speed and as a very resourceful artist.

Sometimes you’ve got to learn to work with what you’ve got. When you’re poor, you’ve got to get creative, you’ve got to learn to roll with it, how to be egalitarian or whatever. You used to go to the drugstore and there was only Viks 44, now you’ve got DayQuil, NightQuil, AfternoonQuil. I’m just saying, they make shit too convenient. But you know what, when you do it the old-fashioned way, it tastes better. It’s like painting: sometimes when shit’s straight out the tube it needs a little something extra.

You’ve painted a portrait of yourself for this show in Somerset, which is rare for you.

I got here and thought about music a lot. I was reading into Peter Noone [the lead singer of 1960s British pop group Herman’s Hermits]. If I was in Arizona I might think about the Hopi or whatever. I tend to think about the peo- ple who live in the land, so when I came here I thought about rock’n’roll, I thought about Chuck Berry, Little Richard. But I didn’t want to overthink it, I just wanted to work. I ran into Peter Noone years ago, and he probably thought I was some homeless motherfucker when I stopped him in the street shouting, “Hey! Stop!” He was shocked. “I’m Henry the Eighth I am!” I’ve been listening to that song since I was five years old! Then I learned about the king and I was just having fun. So I made that painting. Being truthful, I don’t like self-portraiture, but this seemed à propos or something, but normally I don’t give a fuck about self-portraits. I always do them, you know, on the low – I might wake up in the morning and paint a portrait of myself in the bathroom mirror, simply to study. Just like a work out or doing sit-ups.

What about portraits of other people, which in a way are self-portraits – they’re your vision of other people, not how they see themselves. Do people ever react strangely when they see how you’ve painted them?

Oh hell yeah, all the time! People are very conventional. I always give the example that if van Gogh, Picasso, Dubuffet, Goya, all those motherfuckers were there painting at Disneyland and then you had the guys from the local art schools, people would go for the likenesses. “I ain’t paying for something like that with my eyes looking all fucked up!” People always respond when someone goes against the grain. I think of Jimi Hendrix at Woodstock when he plays The Star-Spangled Banner. We all know what the song sounds like. Or like Marvin Gaye. We’re gonna put some funk on it. I’m gonna put me on it. But there’s so many things. My seventh-grade teacher once told me you had 70 conceptions at the same time, so many things going – you might think we’re trying to appease, but we might see something else, like a sycophant, you can be surrounded by yes people. So sometimes I might fuck your shit up! I was painting everyone on a train in Texas once, and the first few came out all accurate and all of a sudden it started getting crazy. And people were saying, “I want mine to look like hers!” That’s where redundancy comes in. We want to describe things, it feels comfortable, but the moment we can’t put a finger on it, when we get lost, we’re fucked. It’s nice to fuck it up. I always want to make something beautiful, but I can’t help it if I get lost. I think about Picasso in his earlier career – representation is important, likeness is important. Everyone starts out representational, but then you fuck it up. That also takes confidence, or at least some kind of freedom, some sort of intuition. We have this tendency when we view something to want to know what it is, what we’re looking at… [Breaks into song.] Oh sorry, I can’t do that!

“Everyone starts out representational, but then you fuck it up.”

What is success to you?

If I can get closer to the truth, or some shit. I contradict myself, I do all that shit, cos I’m always learning. One day someone says, “Oh what shoes you got, they’re kinda funny,” then a few days later you’ve got the same goddamn pair. Whoever is keeping his tongue is keeping his life. Maybe I succumb or I acquiesce to some influence, but I try to really just do me. Sometimes I don’t feel I’ve done shit. It ain’t like I’m Kobe Bryant or Lionel Messi. I’m making paintings, that’s all. Some may like them some may not. Hell, I may not like half the shit I do! And I’m always trying to do something different. I feel like it’s best to be lost before you get found. I don’t mind making scrambled eggs every morning, but the paintings gotta be something else, I’ve got to be free somewhere else. I don’t know if that answers the question. I don’t know if you can make anything of this.

And what are you afraid of?

Not getting to the truth. Some things can be really easy, and I don’t think there’s anything wrong with enjoying. What I’m afraid of is not having fun. I don’t worry about being serious, because I’m already deep. I come from that. That’s always gonna permeate. It’s important to take chances in painting, it doesn’t hurt you. My fear is not taking chances; I want to take chances always. I don’t want to look at some- thing and say, “Woulda, shoulda, coulda.” It’s like telling someone, “I love you,” those are just words, but I had to say it. Sometimes you just gotta paint it.

After his solo show at Hauser & Wirth Somerset, Henry Taylor will present a new show at Hauser&Wirth Southampton (New York), from July 1st to August 1st.

Henry Taylor’s reputation as an artist is almost eclipsed by his rambunctious persona – even via Zoom, his energy is immediate and boundless and the conversation bounces to unexpected places and is punctuated by song. Born in Ventura, California in 1958, he grew up in nearby Oxnard; though he always had a certain predilection for painting, he only pursued it as a profession later in life. After taking art classes in Oxnard, with the legendary James Jarvaise, he went on to complete a BFA at the California Institute of the Arts, graduating in 1995 – until that point, he had been working as a psychiatric nurse at Camarillo State Mental Hospital.

His insatiable curiosity about people and life is perhaps one of the reasons his work is so special.

Taylor is an exceptional portraitist: his fluidity and panache as a painter and sculptor are like no one else working in the US today. He riffs off almost anything you can imagine, incorporating everything and everyone from a racist bumper sticker his brother once saw and told him about to trash thrown in the street, his family, his friend Emory, or Jay-Z and Obama. He freely mixes fact and fiction, memory and story, movement and emotion, and there is no hierarchy between any of these things because Taylor inhabits a higher plane. His insatiable curiosity about people and life is perhaps one of the reasons his work is so special.

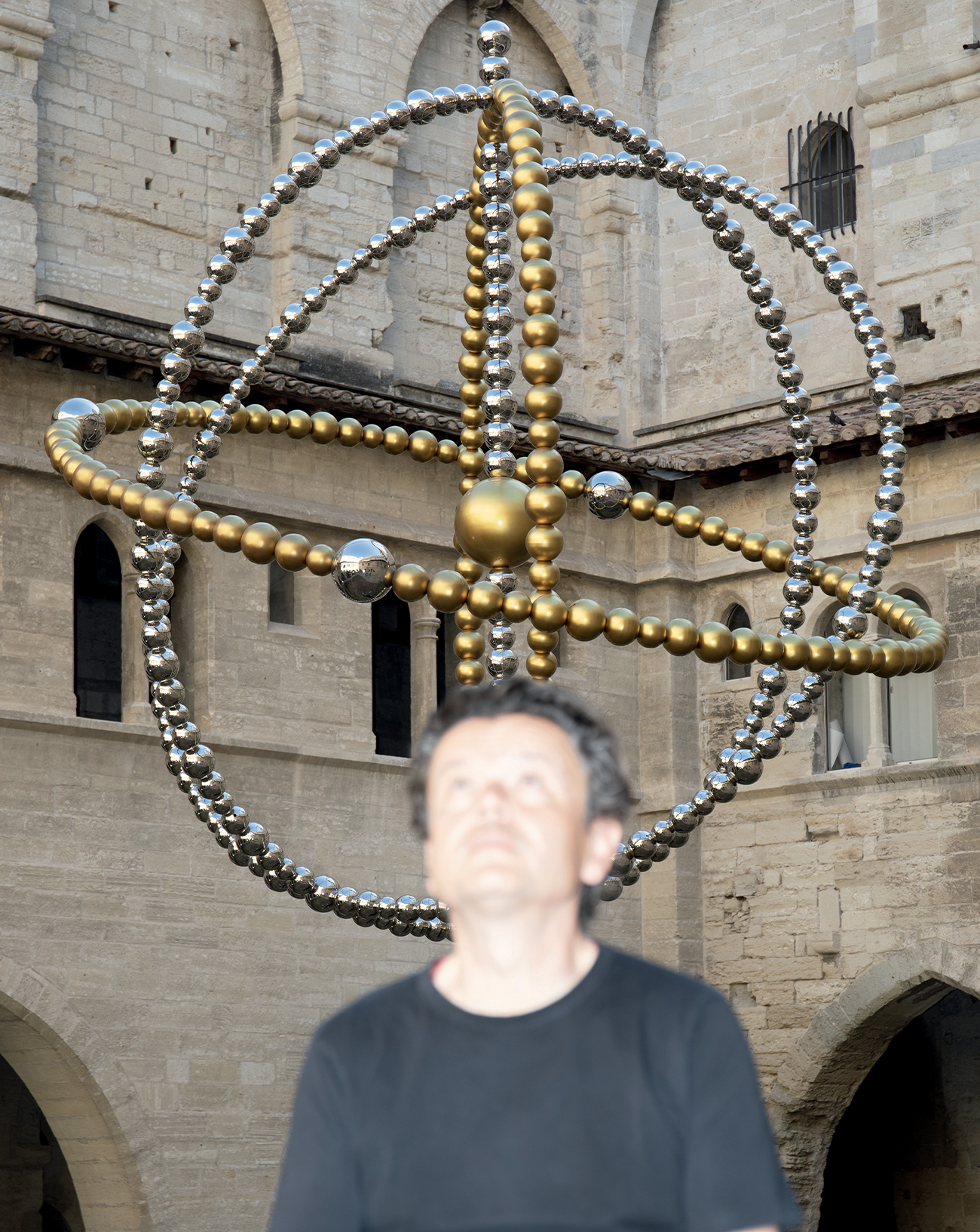

At the time of our interview, it’s the thick of winter and the middle of another lockdown, and Taylor has flown from California to the tiny village of Bruton in Somerset, deep in the English countryside. It’s the last of several weeks he’s spent there on a residency, in preparation for his first major solo exhibition in Europe at Hauser & Wirth Somerset, run- ning until June this year – initially opened online, it includes his first ever outdoor sculpture. Taylor has exhibited consistently across the US since 1999, with his first institutional solo at the Studio Museum, Harlem, in 2007, and a mid-career survey at MoMA PS1 in 2012. In 2022, if all goes to plan, he’ll have major exhibitions at the Fabric Workshop and Museum and MOCA, in Los Angeles, the city that has defined him and that he has defined. His studio is just off Skid Row in downtown LA, and its residents and regulars frequently drift in and out to see him. Sometimes he makes them a meal, sometimes he paints them.

Numéro art: You’re the youngest of eight kids. Tell me about your siblings – I’ve heard that they’re extremely important to you.

Henry Taylor: I have a brother named Ardmore. I didn’t get to know him till much later in life. He’s 78, he was a professor, went to UCSB, he’s a Sagittarius, wild, wacky, crazy, super-cool, love him. [Bursts into song.] Then there’s William Gene, we call him Gene. He was military, he was drafted, he went to Vietnam, came back. He had his own little agenda you know… He said he invented the shag, the hairstyle. He got a doctorate in religion. He lives in Tennessee. Then, my brother Hershel Earl Taylor got shot in Vietnam at the age of 22. I read all of his letters to my mother continuously, so I felt like I had firsthand experience of the war. He died five or six years later in Germany be- cause there was shrapnel in his body and he had a heart attack. Once I was watching a Brad Pitt film and I thought about him all night. His grandson is a world-champion mo- tocross biker, which fucking blows my mind! Hershel was amazing. He wore cufflinks every day, even in high school. He was like that motherfucker from Harlem, Dapper Don. He was slick every day. One night at the MoMA PS1 dinner, I was sitting next to Jerry Speyer, who was wearing gold cufflinks, and I told him about my brother. Jerry Speyer gave me his cufflinks after that story. I didn’t know who Jerry Speyer was. Then there was my sister Anna Laura, who was a civil-service worker and who I loved dearly but who died of cancer. Then there’s Robert, who we call Randy: he’s really smart, a straight-A student. Johnie Ray was named after the singer and he was burned all over his body, and that had a profound effect on me. Then there’s my sister Evelyn, then there’s me. I’m Henry the Eighth I am!

Randy also gave you the idea for one of the main sculptures that’s displayed in your current show.

I made this sculpture here of a guy running with a leather jacket. [Bursts into song.] You see this sculpture? So one day my brother Randy said, “Henry! I saw a bumper sticker that read ‘I couldn’t find me no deer so I shot me a nigga.’” It was probably in Texas or somewhere. And I made this sculpture which is here now. Randy started a Black Panther chapter. That sculpture has a leather jacket on it, and for a minute there I wasn’t sure about the jacket, but then a lot of people said, “Hey, your brother had us wear leather jackets like Huey Newton.” What else do you want to know?

“I’ve been a listener all my life – being the youngest you don’t always get to talk, so you observe.”

Well, you were the youngest, so were you always the cute one, the one that got all the attention?

You think I’m cute? Golden nugget, that was my nickname! I never thought I was cute. I always had this high forehead and people used to grab my head and shout, “NUGGET!” So honestly I never felt like that. But I was the youngest and you get to hang out with a lot of people. I got to hang out with my dad who was actually a painter, an industrial painter, and from an early age, five or six years old, I went to hang out with him and watch him paint. I was very close to my mom. My parents divorced and I lived with my dad when I was 19 and there’s things I know about him that my siblings don’t. He told me all kinds of things, like about the day my grandad got shot, when my dad was nine years old, and what he did. I felt very privileged, for lack of a better word. My mom would ask me to come wash her back, sitting nude in the bathtub. Everything was so fucking natural. My mom would tell me stories, like about where she got the scars on her knee. She talked about objects like scars. I met people on Skid Row who told me they were the first Rodney King riot-victims and showed me the scar on their head where they’d been beaten with a flashlight. It made me a listener, too. I’ve been a listener all my life – being the youngest you don’t always get to talk, so you observe.

Is that where the storytelling came in? Observation is so important when it comes to painting portraits…

I think I thought about painting when I was five years old, but I never did it. I was already seeing stories, I was peeping in and out. I wanted to be a writer, but I’m too angsty for that, it takes too much discipline.

How about your dad? You once made a film about him witnessing your grandfather getting shot when he was just a child.

My dad used to call his sons bullets. Where the fuck did that come from? It didn’t occur to me until 20 years later, when I was on a residency in Texas and they said I could make a film. What I’m saying is that a lot of shit doesn’t resonate right away – he called us bullets because his dad got shot, he got six boys, and there are six bullets in a re- volver. My dad was creative like that – I thought of him like a poet. I put words of his on the wall when I graduated from CalArts. He was challenging people all the time. Sometimes we don’t acknowledge people. On my birth certificate it says “Father’s occupation: painter.” Didn’t mean much to me. Then I said, “Damn, ain’t that a trip! Used to watch him paint. Walls, and shit. There’s something there.” You see your dad run, may not be sprinting, patterns. My dad did, my brother, who was a barber, cut faster than anyone, so speed became a big factor in my painting. I always wanted to paint fast. I’d think about him.

You’re known both for your speed and as a very resourceful artist.

Sometimes you’ve got to learn to work with what you’ve got. When you’re poor, you’ve got to get creative, you’ve got to learn to roll with it, how to be egalitarian or whatever. You used to go to the drugstore and there was only Viks 44, now you’ve got DayQuil, NightQuil, AfternoonQuil. I’m just saying, they make shit too convenient. But you know what, when you do it the old-fashioned way, it tastes better. It’s like painting: sometimes when shit’s straight out the tube it needs a little something extra.

You’ve painted a portrait of yourself for this show in Somerset, which is rare for you.

I got here and thought about music a lot. I was reading into Peter Noone [the lead singer of 1960s British pop group Herman’s Hermits]. If I was in Arizona I might think about the Hopi or whatever. I tend to think about the peo- ple who live in the land, so when I came here I thought about rock’n’roll, I thought about Chuck Berry, Little Richard. But I didn’t want to overthink it, I just wanted to work. I ran into Peter Noone years ago, and he probably thought I was some homeless motherfucker when I stopped him in the street shouting, “Hey! Stop!” He was shocked. “I’m Henry the Eighth I am!” I’ve been listening to that song since I was five years old! Then I learned about the king and I was just having fun. So I made that painting. Being truthful, I don’t like self-portraiture, but this seemed à propos or something, but normally I don’t give a fuck about self-portraits. I always do them, you know, on the low – I might wake up in the morning and paint a portrait of myself in the bathroom mirror, simply to study. Just like a work out or doing sit-ups.

What about portraits of other people, which in a way are self-portraits – they’re your vision of other people, not how they see themselves. Do people ever react strangely when they see how you’ve painted them?

Oh hell yeah, all the time! People are very conventional. I always give the example that if van Gogh, Picasso, Dubuffet, Goya, all those motherfuckers were there painting at Disneyland and then you had the guys from the local art schools, people would go for the likenesses. “I ain’t paying for something like that with my eyes looking all fucked up!” People always respond when someone goes against the grain. I think of Jimi Hendrix at Woodstock when he plays The Star-Spangled Banner. We all know what the song sounds like. Or like Marvin Gaye. We’re gonna put some funk on it. I’m gonna put me on it. But there’s so many things. My seventh-grade teacher once told me you had 70 conceptions at the same time, so many things going – you might think we’re trying to appease, but we might see something else, like a sycophant, you can be surrounded by yes people. So sometimes I might fuck your shit up! I was painting everyone on a train in Texas once, and the first few came out all accurate and all of a sudden it started getting crazy. And people were saying, “I want mine to look like hers!” That’s where redundancy comes in. We want to describe things, it feels comfortable, but the moment we can’t put a finger on it, when we get lost, we’re fucked. It’s nice to fuck it up. I always want to make something beautiful, but I can’t help it if I get lost. I think about Picasso in his earlier career – representation is important, likeness is important. Everyone starts out representational, but then you fuck it up. That also takes confidence, or at least some kind of freedom, some sort of intuition. We have this tendency when we view something to want to know what it is, what we’re looking at… [Breaks into song.] Oh sorry, I can’t do that!

“Everyone starts out representational, but then you fuck it up.”

What is success to you?

If I can get closer to the truth, or some shit. I contradict myself, I do all that shit, cos I’m always learning. One day someone says, “Oh what shoes you got, they’re kinda funny,” then a few days later you’ve got the same goddamn pair. Whoever is keeping his tongue is keeping his life. Maybe I succumb or I acquiesce to some influence, but I try to really just do me. Sometimes I don’t feel I’ve done shit. It ain’t like I’m Kobe Bryant or Lionel Messi. I’m making paintings, that’s all. Some may like them some may not. Hell, I may not like half the shit I do! And I’m always trying to do something different. I feel like it’s best to be lost before you get found. I don’t mind making scrambled eggs every morning, but the paintings gotta be something else, I’ve got to be free somewhere else. I don’t know if that answers the question. I don’t know if you can make anything of this.

And what are you afraid of?

Not getting to the truth. Some things can be really easy, and I don’t think there’s anything wrong with enjoying. What I’m afraid of is not having fun. I don’t worry about being serious, because I’m already deep. I come from that. That’s always gonna permeate. It’s important to take chances in painting, it doesn’t hurt you. My fear is not taking chances; I want to take chances always. I don’t want to look at some- thing and say, “Woulda, shoulda, coulda.” It’s like telling someone, “I love you,” those are just words, but I had to say it. Sometimes you just gotta paint it.

After his solo show at Hauser & Wirth Somerset, Henry Taylor will present a new show at Hauser&Wirth Southampton (New York), from July 1st to August 1st.