7

7

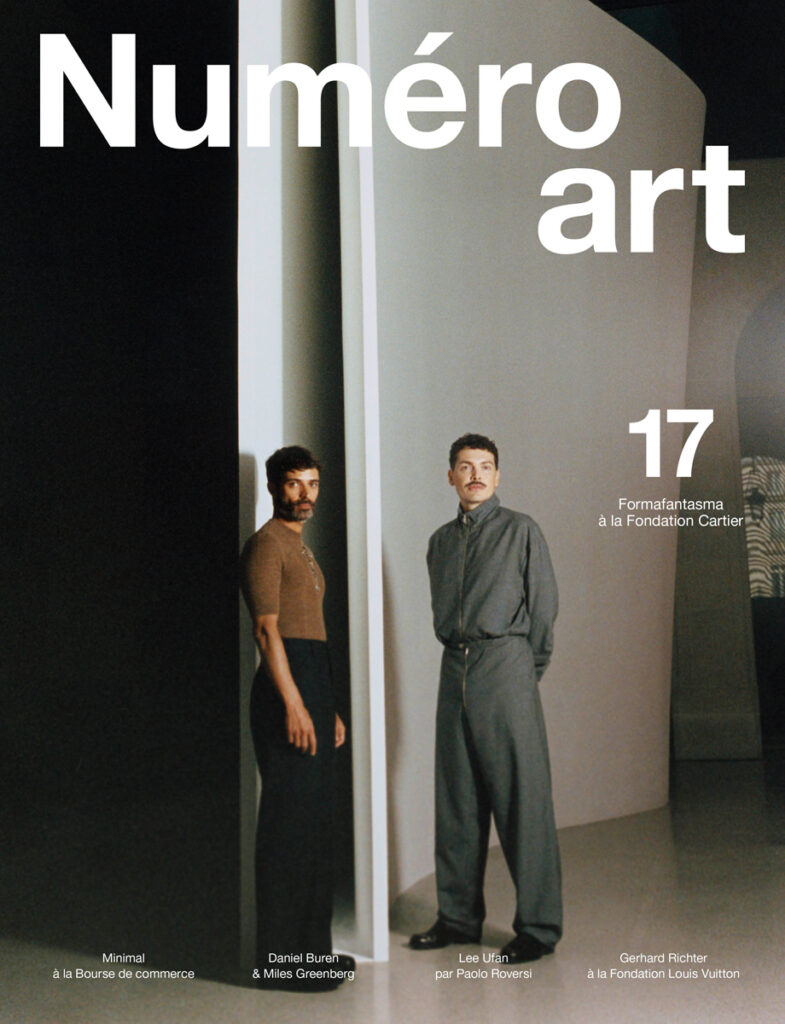

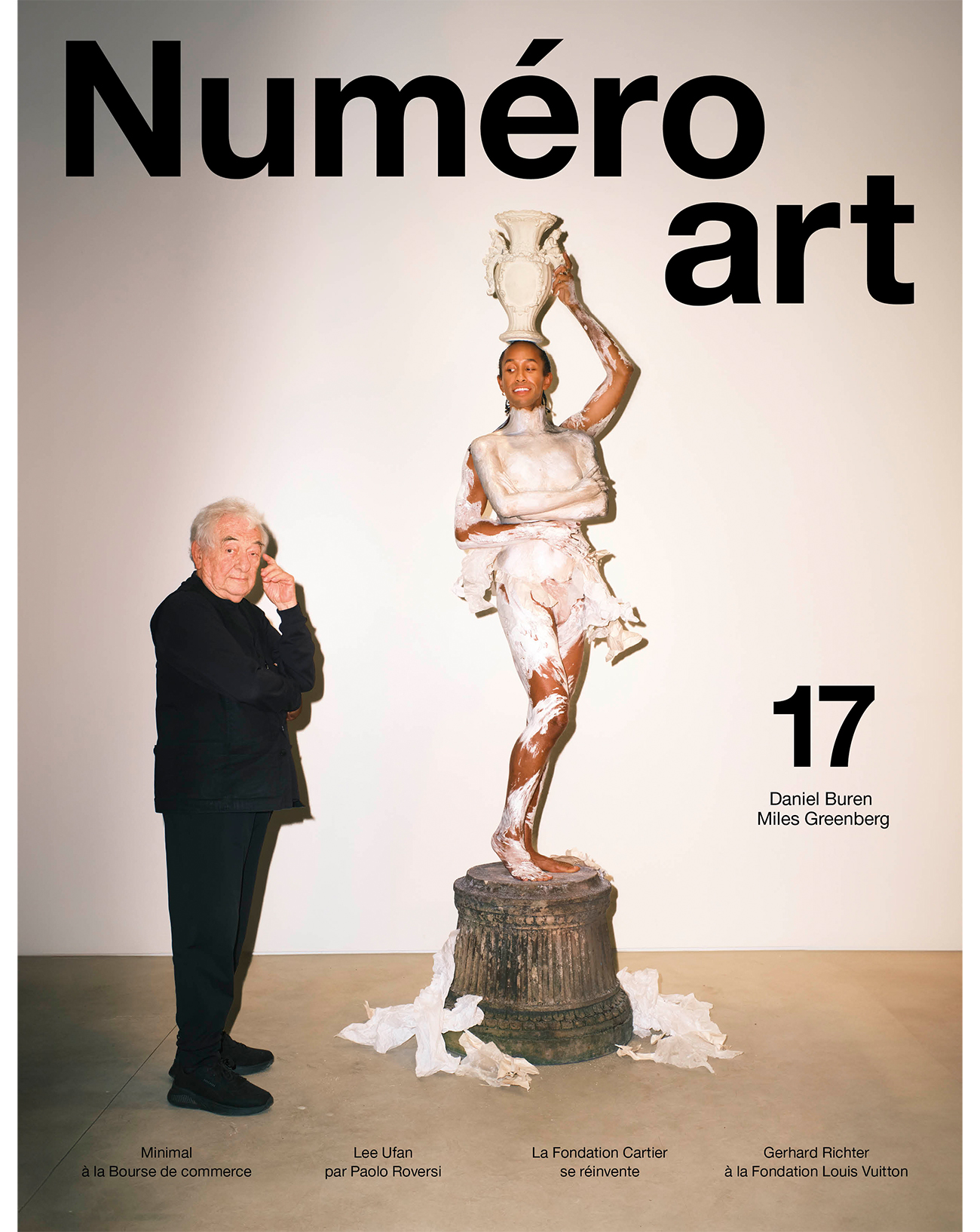

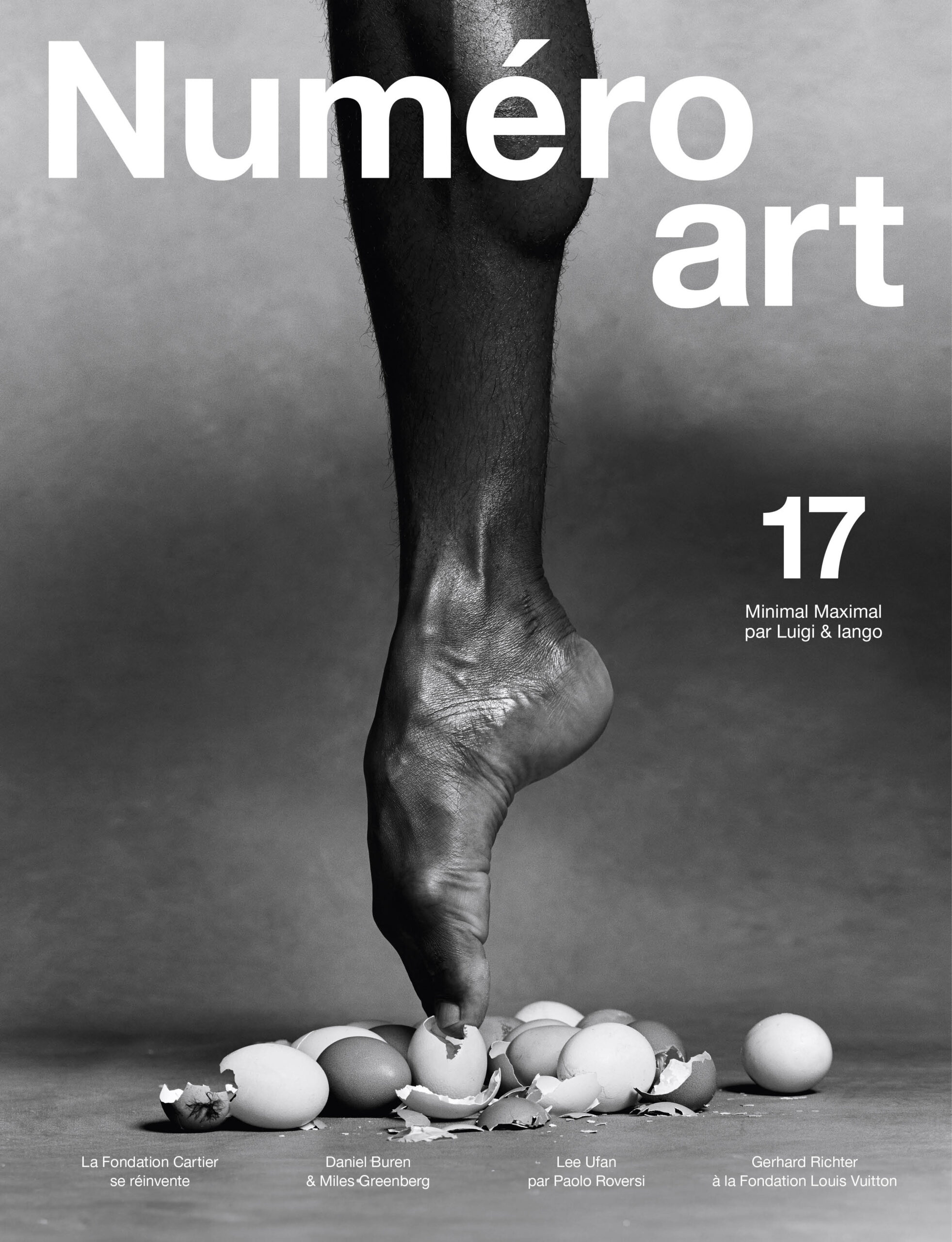

Fondation Cartier: The duo Formafantasma unveils the new space with its director Chris Dercon

After 30 years at its Rive Gauche address, the Fondation Cartier has crossed the Seine to a new home in the place du Palais-Royal, which it has inaugurated with a show featuring 600 pieces from its collection. Formafantasma, the exhibition designers, took Numéro art on a preview tour, during which they recounted the show’s genesis in the company of Chris Dercon, the foundation’s director.

Interview by Jean-Marie Durand, photos by Nick Chard .

Hair and makeup: Cicci Svahn at Calliste Agency. Assistant photographer: Louis Jay. Retouching: Notion.

Numéro art 17 is available at newsstands and on iPad since October 18th, 2025.

The Fondation Cartier opens its new space in front of the Louvre

This autumn, the Fondation Cartier pour l’art contemporain took up residence in Paris’s place du Palais-Royal, just opposite the Louvre, in a Haussmann-era building entirely renovated by the architect Jean Nouvel. To inaugurate its new home, the foundation’s director, Chris Dercon, decided to display a selection of 600 iconic pieces from its holdings. Titled Exposition générale and imagined as a “statement,” the show seeks to underline the breadth and coherence of an exceptional collection that is marked by a taste for transdisciplinarity, cultural diversity, attention to all forms of the living, craftsmanship, architecture, and science…

A building reinvented by Jean Nouvel and a space reimagined by Formafantasma

In the heart of the 19th-century building, Nouvel has installed five hydraulic platforms, which allow a certain porosity between the works as well as great fluidity of visitor circulation. For the exhibition design, the foundation called on Italian design duo Formafantasma (Simone Farresin and Andrea Trimarchi), in keeping with a drive to reimagine the way art is shown: breaking with the white cube approach, Exposition générale favours circularity, openness, transparency, and a plurality of forms. For Numéro art, Dercon and Formafantasma sat down to discuss the show’s curatorial goals.

Joint interview with Chris Dercon and Formafantasma

Numéro art: Why did you choose to show the foundation’s collection, rather than the work of a single artist, for the opening of the new building on the place du Palais-Royal? Chris Dercon: The collection has been shown several times before, but never in a way that allows visitors to understand its scope and richness. When I talk with Parisian friends and even colleagues, I realize that almost no one is really familiar with the collection. People have heard of it or read about it, but it’s never really been made visible. I like the word “visible,” because it also refers to Formafantasma’s work. They’re “display designers,” which is to say that they work on the cusp of design, industrial design, and architecture, somewhere between anthropology and sociology. For me, they embody a new generation of “practitioners of the in-between.” “Display” comes from the Latin displicare, which means “to unfold, or make visible.” The point of exhibiting the collection is to make visible the history of the Fondation Cartier, to show that it’s very different from other private collections because it’s transdisciplinary. I don’t mean to say “interdisciplinary,” but “transdisciplinary.”

What does “transdisciplinary” mean for you? Chris Dercon: I’m using the word in the sense of “situated between disciplines,” which is to say between art and design, between design and architecture, and between art and craft. Our collection represents multiple disciplines, and Exposition générale is a unique opportunity to make visible this sort of in-between. That’s what sets us apart from most other institutions.

“Formafantasma work between anthropology and sociology. For me, they embody a new generation of “practitioners of the in-between.’” – Chris Dercon

In what ways does Nouvel’s building contribue to this idea of the in-between? Chris Dercon: Jean Nouvel’s building is very open and creates a real sense of dialogue, because it allows the pieces to converse among themselves. The collection was built up over the course of different exhibitions: sometimes we’d buy entire shows, at others only a few selected pieces, and at others just a single work, as with Olga de Amaral and Damien Hirst. We’ve also acquired commissions. Little by little, the visitor understands – as Italian philosopher Emmanuele Coccia writes in the catalogue – that the collection and the exhibitions function when one work reacts to another. And that becomes visible once more – I insist on the word. Nouvel’s building lends itself perfectly to this: it creates this visibility.

There’s another reason we called the show Exposition générale. In the 19th century, with the rise of the Parisian department store, people spoke of “salons of modernity” and “general exhibitions.” Think of Colette, the concept store, which displayed the tools and signs of modernity, including works of art. We really like this idea, especially since we’re right opposite the Louvre. So we decided to keep the term.

Our building gives onto the rue Saint-Honoré and the rue de Rivoli. Formafantasma and our curators understood this well. We can play with this idea of visibility, making the interior visible from the street, and vice versa. There’s a unique moment in the exhibition where you see two works by Chéri Samba and, at the same time, on the other side of the street, visitors looking at Greek and Roman sculptures in the Louvre. It’s amazing!

“The way the Fondation Cartier establishes relationships between architecture, art, photography, and numerous other disciplines is highly contemporary. It doesn’t seek to ‘equalize’ but to ‘connect’. ” – Simone Farresin

Simone and Andrea, what struck you the first time you saw Nouvel’s building? What were your guiding principles when you started working in the space? Simone Farresin: Chris is right in describing our work as being between disciplines – that’s exactly what we’re trying to do. We always say that our work is ambiguous, but we consider this ambiguity a strength. It also reflects the complexity of the world. Being just one thing is no longer enough; it’s better to be multiple. In our work, we try to embrace this ability to be several things at once. For us, the building’s key quality is that it’s almost indifferent to art. By that I mean that it doesn’t correspond to the usual white-cube context we’ve become used to for the display of contemporary art.

Here we understand that the idea is to see all the works in relation to one another. It’s very exciting. It allows us to question contemporary art and preconceived ideas about how certain works should be shown. That’s how we work, too. We’re not here simply to serve the work, but to make an exhibition that says something with the work. We think there’s no such thing as complete neutrality. You can’t just serve the work without saying anything.

Andrea Trimarchi: Our initial reaction was indeed one of interest in what such an open building could offer. We and the curatorial team immediately understood that we wanted to interfere as little as possible with the architecture. We wanted both to exhibit the works and show Nouvel’s architecture to advantage, not because we sought to serve it, but because we found it stimulating. This was all the more important given that this is the first exhibition in the building, so it’s the first time the public will be seeing it. We wanted to maintain as much as possible the opportunities it offers for establishing relations between works.

Simone Farresin: Another aspect, which Chris has already mentioned and which I consider essential, is the word he used, “transdisciplinary.” The way the Fondation Cartier establishes relationships between architecture, art, photography, and numerous other disciplines is highly contemporary. It’s not like at the MoMA, which has specific departments. Here, there are no departments. The foundation doesn’t seek to equalize but to connect. The building is perfect for that. Its history is another source of inspiration. We wanted to make discreet references to its commercial past through the materials we used, for example by including textiles in the display design. We’re not just looking at the museographic tradition, but also at traditions of furniture design and materiality.

Andrea Trimarchi: One can’t deny the complexity of working in such a building, where some spaces have low ceilings and others are vast. You have to take that into account when designing the exhibition. But it also offers a huge advantage, which is that you’re not limited to thinking about the display solely from the visitor’s horizontal perspective, since you can build galleries vertically. For example, we’ve “suspended” certain works, as though they were floating in space. You can be on the ground floor and look up at works on a completely different scale, floating in the air.

“We were adamant the exhibition shouldn’t become monumental, as in spectacular. We wanted to maintain the intimacy of the old building.” – Simone Farresin

Chris Dercon : You use the word “scale.” I love that, because this building isn’t obsessed with size, like a lot of others. There’s a big difference between size and scale. Size is something you can choose: large, small, immense. Scale, however, is a human dimension. It’s given to you, it’s not a choice. In this building, David Lynch’s small drawings work at the same scale – I’m not talking about size – as Richard Artschwager’s tree trunk.

So we can’t be accused of spectacularizing our spaces, as we often see in certain biennials or museums. It’s what’s sometimes called XXL art, blown up to extremes, which has nothing to do with scale, sculpture, or architecture. Here, it’s different. We combine the questions raised by design, architecture, painting, and sculpture. And we can combine them because Andrea, Simone, and I have been working around a key concept, namely scale.

Simone Farresin: Yes, it’s essential. From the outset, we knew there’d inevitably be monumental moments, but we were adamant the exhibition shouldn’t become monumental, as in spectacular. We wanted to maintain the intimacy of the old building on the boulevard Raspail, to show smaller works, and to give visitors the chance to experience these multiple scales. And, to be honest, the building allows that, because it offers both very intimate and vast spaces. That was our goal from the start: to prove you can still show intimate works despite the complex spatiality.

Chris Dercon: There’s often a problem with things that move in multimedia exhibitions, by which I mean videos and machine-like kinetic installations. Strangely enough, when I went back to Nouvel’s building this morning, I realized it’s a kind of viewing machine, an observation machine. And, amazingly, this time the videos work really well with the still works. Kinetic installations like Sarah Sze’s interact perfectly with the fixed works because the building itself also has this machine-like quality. There’s a dynamic relationship, which also comes from there being a dynamic observer, almost like in Caillebotte’s paintings or Piranesi’s drawings. The visitor’s movement in space is key. You can watch people watching other people, which creates this really fantastic tension.

“The value is intrinsic and cultural, not just financial. You can’t speculate with these works.” – Chris Dercon

Simone Farresin: Absolutely. Because of the way the building is designed, it stages the visitors as much as the works of art. You see the visitors and the works together, as if the display case had been opened up to let them in. We’ve always tried to do this in our own work, but here, the building does it all by itself. I should add that, despite its complexity, it offers an impression of freedom. I don’t really like that word, but you get the feeling that certain works, normally seen in a white cube, express themselves better outside that context, as though they were grounded in a reality, that of the building, the street, and the visitors. It’s very refreshing for contemporary art, as we saw recently at Wolfgang Tillmans’s exhibition at the Centre Pompidou. Breaking away from the white cube can enhance the art.

Chris Dercon: One shouldn’t conclude that the white cube is inherently bad. Far from it. But we offer a very valuable alternative. What Formafantasma does – or what Wolfgang Tillmans and other artists have always done – helps us rethink what it means to exhibit. In the 1920s and 30s, people knew how to do that really well, and then it was mostly forgotten. It came back with Carlo Scarpa and Lina Bo Bardi, but it remained a footnote.

“We want to anchor the works in a reality – our reality, the building’s, the city’s – rather than in abstraction.” – Simone Farresin

In French, exhibition design is known as scénographie. What does that word conjure up for you? Simone Farresin: We don’t like the word scénographie because it evokes the theatre, something artificial. We also dislike the moveable partitions typical of the white cube, which pretend to be neutral but aren’t. For Exposition générale, we designed display structures in metal and fabric. Some artists might not like being shown on such bold design pieces, but for us it’s important. We want to anchor the works in a reality – our reality, the building’s, the city’s – rather than in abstraction. We’re Italian, we grew up seeing the likes of Franco Albini, Carlo Scarpa, BBPR, the Castello Sforzesco. Italy has a fantastic tradition of exhibition design. We started doing this because we were disappointed by a lot of shows, but were fascinated by those where the design adds a real layer to the work and connects very different pieces in the same space.

Chris Dercon: One might also say that you stage the exhibition itself: it’s a performance. Visitors feel that – there’s great potential for interaction.

Andrea Trimarchi: Yes. There’s also a purely functional aspect. We talked a lot with the curatorial team about visitor flow. You can go up and down, and see things from different angles. There were two options: either a very specific circuit, which would have required closing off parts of the building, or a suggestion, with vertical markers visible everywhere so that visitors could find their way around intuitively. Like in a city, where an emblematic building, such as Brunelleschi’s cathedral in Florence, guides the eye.

“Transdisciplinarity between design and architecture, between painting and sculpture, between art and craft, is what really makes this collection stand out.” – Chris Dercon

What makes the collection so contemporary? Its openness to so-called “minority” cultures? Its transversality? Its openness to all forms of life? Its way of dehierarchizing life forms? Its openness to craft? Chris Dercon: For me, like I said at the beginning of our conversation, the most important thing is the transdisciplinarity between design and architecture, between painting and sculpture, and between art and craft. That’s what really makes this collection stand out. Art Basel collectors will say, “But I don’t see these artists at Sotheby’s or Christie’s! How much are they worth?” The value is intrinsic and cultural, not just financial. You can’t speculate with these works. It’s an investment in culture, and that gives us a lot of freedom to go find art where no one else is looking and acquire works by local artists, for instance.

That’s what makes the Fondation Cartier different: it holds up another mirror to the diversity of cultural creation. A work like Exit by Diller Scofidio + Renfro, based on an idea by Paul Virilio, charts population movements around the world, evolving with real-time events, continually updating through data. It’s a work that’s typically outside the market.

Simone Farresin: In contrast to the finance-driven art market, this collection is proof that there are works that can only exist in an institution. Not that everything sold at auctions is bad per se, but it’s also crucial to show what escapes the market. We know that many of the works currently on display in the New York galleries, in the Meatpacking District, are there because they’re easier to exhibit.

Chris Dercon: The collection and the show Exposition générale, with its humble, somewhat ironic title, raise new questions that go beyond debates about identity, globalism, and decolonization. We’re opposite the Louvre, like a mirror of our world. For me, one of the greatest pleasures is arriving in the morning, and seeing the passers-by on the rue de Rivoli, and at the same time the Louvre opposite getting ready to open. It’s almost like Flaubert’s Bouvard et Pécuchet or Calvino’s Invisible Cities transposed to the 21st century.

Opening of the new premises of the Fondation Cartier on October 25th, 2025, 2, place du Palais-Royal, Paris Ier. “Exposition générale”, from October 25th, 2025, to August 23rd, 2026.