11

11

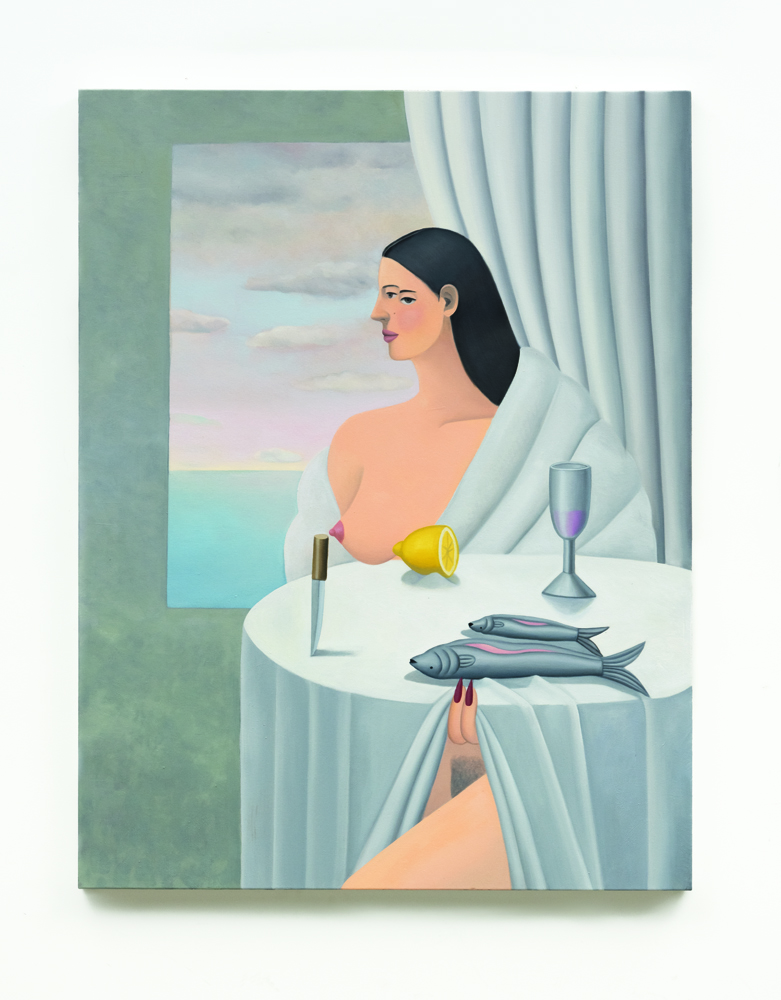

Ambiguous eroticism and spectator-voyeur: the enigmatic canvases of GaHee Park

When contemplating her unsettling canvases, we the beholders are turned into voyeurs, scrutinizing erotic Surrealist scenes that evoke distant memories of the painter’s childhood…

By Éric Troncy.

Published on 11 November 2024. Updated on 13 November 2024.

GaHee Park’s art: a tool for emancipation

Fun and Games, her show at Perrotin New York just before the summer, once again demonstrated the extreme particularity of her work, which Australian art critic Jennifer Higgie has described as “fantastical, sensual, occasionally sinister.” It’s all of that and more, filled with oddities such as the recurring presence of fish and crustaceans, which, whether or not they are meant to be characters, always seem to be still lifes. She paints for an audience, but also in order to see – to see where her mind leads her, where her fantasy takes her – using the medium as a tool for introspection.

Though it is not autobiographical, the work maintains the fundamental link between itself and its author’s personal history – after growing up in Asia, she used painting as an instrument of emancipation and liberation. Where the fish are concerned, GaHee Park attempts a justification. “My grandmother sold fresh fish in a market in Korea, and I have always spent time with dead fish and seafood. Observing them from a young age probably makes me want to paint them. There is something familiar about them for me, but they also still seem very alien.” Where the rest is concerned, her ideas are less literal. “It’s difficult to dissect individual motifs. They all come out of some combination of what they mean and what they look like… How they invoke themes, subjects, or moods that interest me, and how they function as formal elements of the com-position. And then, also, what kind of loose narrative they spark for me.”

A talent that takes root in a garden of kakis…

She was born in 1985 in Seoul, where she lived till the age of 20, to parents she describes as “very Catholic,” and who had very particular ambitions for her. “They wanted me to get married, be very Catholic, teach the Bible at church. Initially, they wanted me to become a pianist, but honestly, I was very bad at it.” Dismayed by the young GaHee‘s lack of pianistic prowess, and aware that she spent most of her time sketching, they sent her to a drawing class run by an old lady whose garden, she remembers, was planted with kakis – today they feature in some of her pictures.

She went every afternoon, and without realizing it acquired a solid technique. Above all, she found an outlet for her incomprehension of Korean society, which seemed unbearably sexist to her. In her sketch-books, she drew both male and female genitalia, and then glued the pages together so that her mother, who took to searching her bedroom when she discovered she’d starting smoking, wouldn’t see them. “I guess it’s common, kids with Catholic up-bringings, such as myself, getting naughty,” she remarks.

GaHee Park’s journey between sacrifice and freedom

When she announced that she’d like to go to the US to learn English, her parents negotiated. “They said, ‘Well, if you teach Bible at church for a year, we’ll send you to America to study English.’” She accepted without flinching, getting up every morning at five to play the organ in church. Afterwards, “they sent me to America, to Miami, where to be honest I just partied every night for a year, nonstop.”

Returning to Seoul was brutal. “My colleagues, students, started calling me a whore because I had been to America...” So she went to study art in Philadelphia. She remembers Dona Nelson, one of her professors. “She would rent a car, a really fancy American car. And from Philadelphia she would drive some students, if they wanted to follow her, to the Met, where she was screaming with excitement in front of each and every painting displayed there. We went there five times a year, and every time she went to the same painting, a Balthus, and yelled at it that it was the best!” Like the other faculty at the Tyler School of Art in those days, Nelson taught abstract painting, a fact that is useful to know when contemplating Park’s œuvre.

“I also do not want to express certain emotions. I feel it’s not fair for artists to give everything .”

GaHee Park

Whether they are still lifes or situations featuring characters, her paintings always seem to be still lifes. The characters, animals, or fruit play an identical role as decisive elements in both the composition and the narration. Always completely immobile – either lying down or striking a pose – her characters do nothing important or symbolic, and express almost no emotion. She offers a curious explanation for that: “I also do not want to express certain emotions. I feel it’s not fair for artists to give everything.” Hovering in her pictures, we see the shadow of Balthus, but also of the Douanier Rousseau, as well as memories of Surrealism and Italian Mannerism – as in much contemporary figurative work, she combines a plethora of different influences.

In front of GaHee Park’s canvases, the viewer becomes a voyeur

In the way she paints hair, one recognizes Fernand Léger; in her slightly modelled expanses of colour, there’s a bit of Alex Katz; in the exposure and posture of the body a touch of Pierre Molinier; in the characters with impossible eyes or three mouths a dash of Cubism. She primarily paints domestic scenes, but the beholder is always placed in the position of voyeur, and something rather incongruous comes through: everything, right down to the fruit and flowers – she has a clear preference for anthuriums – seems to have erotic connotations.

“I love beautiful things. I just can’t help myself indulging things around me, I think it’s given to us. But I can use those things to fight against something that is built by, you know, some manmade idea,” she says. And indeed, on the surface of her pictures, we find a cohabitation between a certain form of calm expressed through a style that is almost decorative (perfect skin, as though we were seeing it through a TikTok filter) and the indistinct urges of all sorts of improprieties. Nothing is explicit; ambiguity is cultivated as a cardinal virtue.

We must make do with what we’re given and allow ourselves to be troubled by the slightest detail. And so it was that her decision to paint, on the table in Under Cover (2023 – one of the works shown in New York), two fish that seem to have been gutted (rather than two whole fish, as you would find them in nature), appeared to me to have nothing obvious about it. Just like the slight protuberance, on the surface of a white tablecloth, that keeps half a lemon in place. Often unconsciously, the mind records these seemingly minor details like so many gremlins that hinder reasoning; freeing us from a single reading, they transport us to the joys of the equivocal.

Her œuvre – as could be seen in the New York show – has evolved away from its origins. GaHee Park now seems freed from the need for personal storytelling, as though, after contributing to her emancipation, the stories have in turn decided to let her go. “For a while, I thought I was working on identity, because my experience really mattered. You know, relationships with my parents, my homeland. I don’t think identity or my own experience inspire me that much anymore,” she concurs. “Besides, I don’t even paint Korean characters!”