22

22

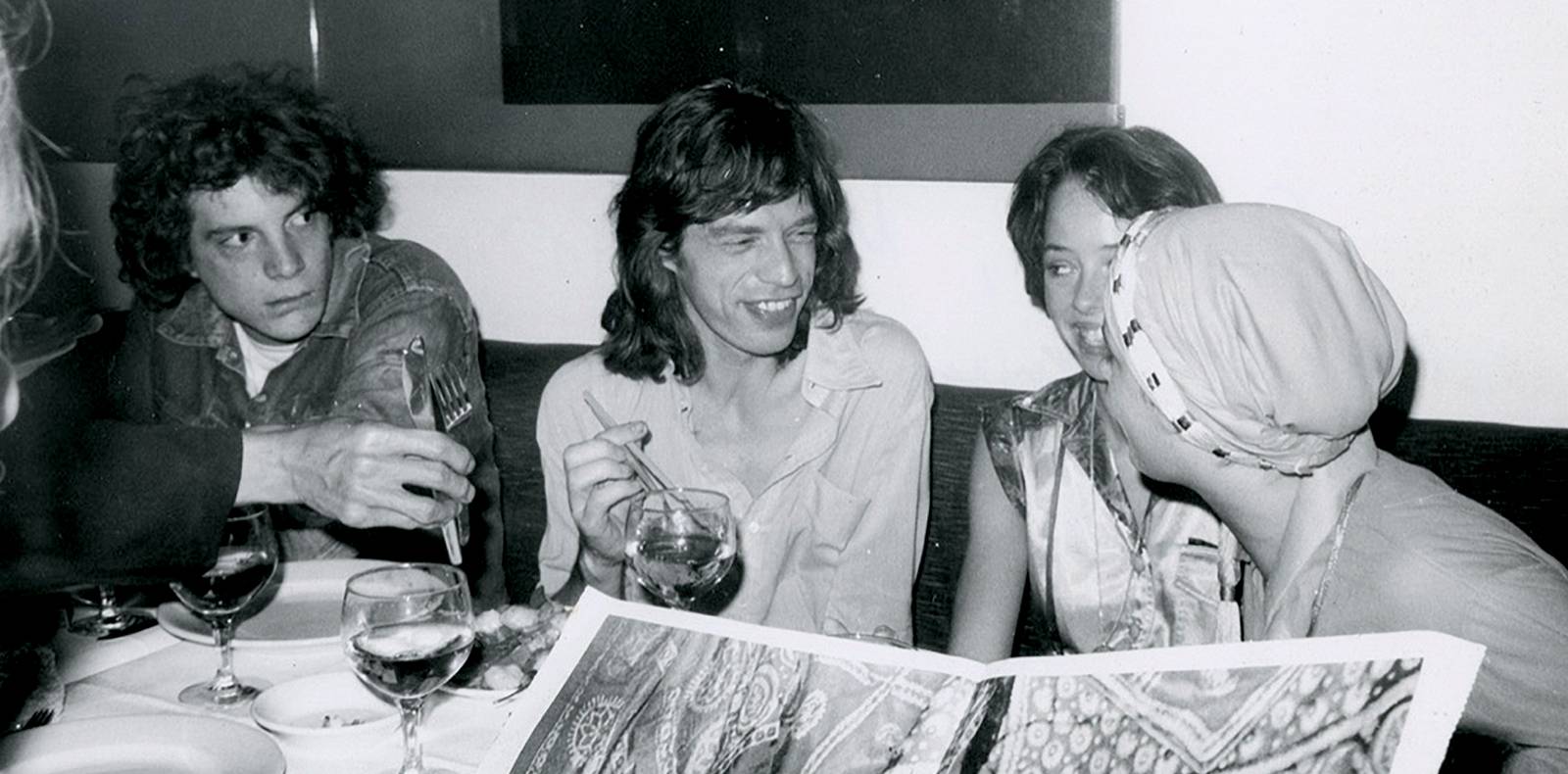

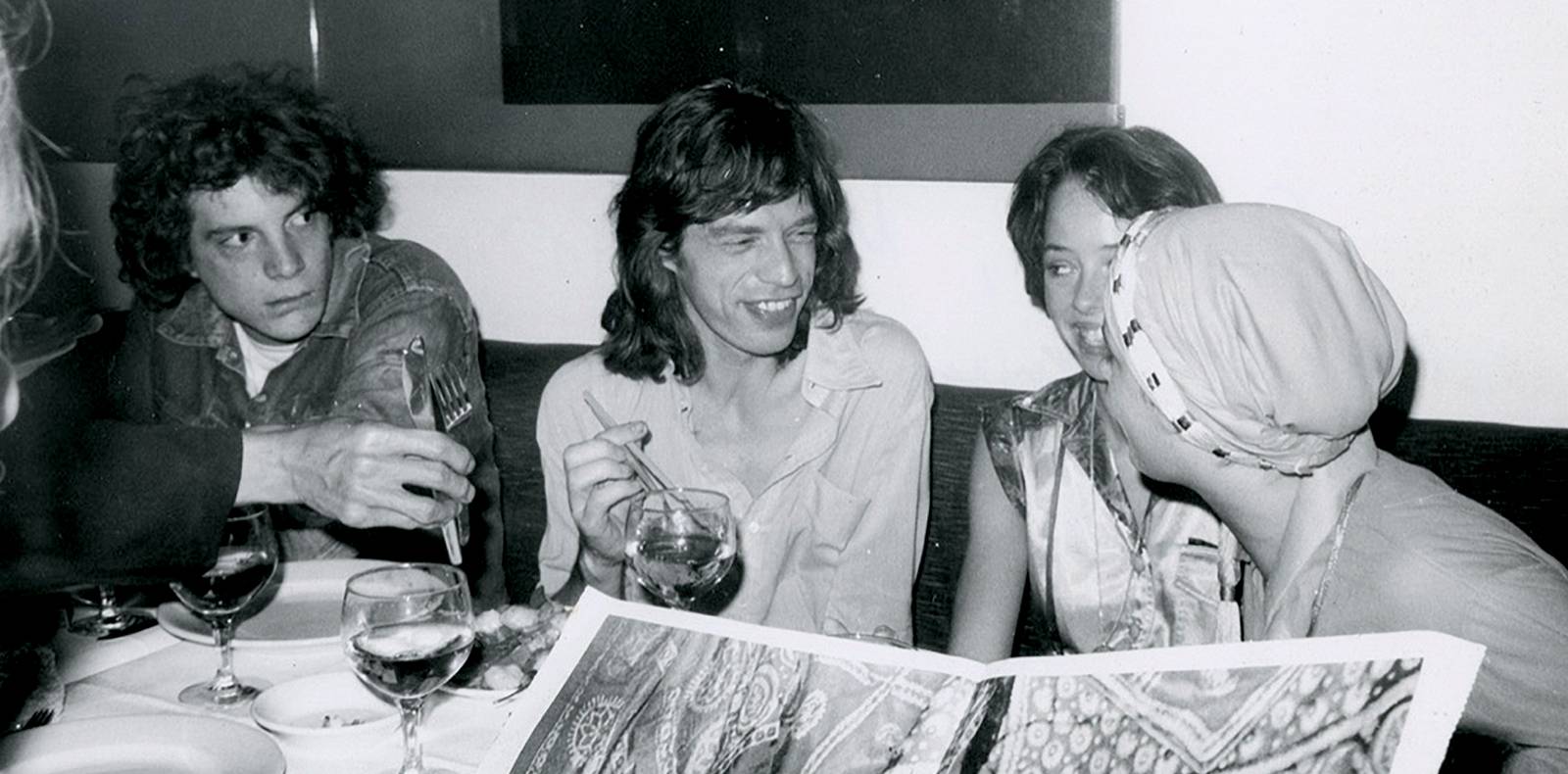

Andy Warhol, Mick Jagger : jet set life as seen by Bob Colacello at the Ropac gallery

Proche d’Andy Warhol, Bob Colacello côtoya l’avant-garde et la jet-set, dont il immortalisa les fêtes et la vie quotidienne. A la galerie Thaddaeus Ropac à Paris, ce photographe expose jusqu’au 4 mars ses clichés pris entre 1976 et 1982, dépeignant une époque de grande liberté.

Par Éric Troncy,

By Éric Troncy.

Il est né à Brooklyn en 1947 et a grandi à Long Island, New York. Aujourd’hui, il travaille pour la fondation d’art créée par Peter Marino, la Peter Marino Art Foundation, dans les Hamptons. Son statut actuel de légende vivante ne dépend pas totalement du livre qu’il a publié en 2004, consacré à Ronald et Nancy Reagan (après sa publication “la moitié du monde de l’art a cessé de me parler”, se rappelle-t-il, ce qui ne l’empêche pas d’envisager d’écrire prochainement le deuxième tome), mais repose avant tout sur les moments qu’il a passés auprès d’Andy Warhol dans les années 70. Des moments qu’il documenta frénétiquement avec son appareil photo, un petit Minox qu’il trimbalait toujours avec lui : 80 de ses photographies réalisées entre 1976 et 1982 sont aujourd’hui exposées à la galerie Thaddaeus Ropac de Paris (Marais), accompagnées d’un livre qui les rassemble et s’intitule It Just Happened.

Bob Colacello, un photographe qui a côtoyé de près la jet-set

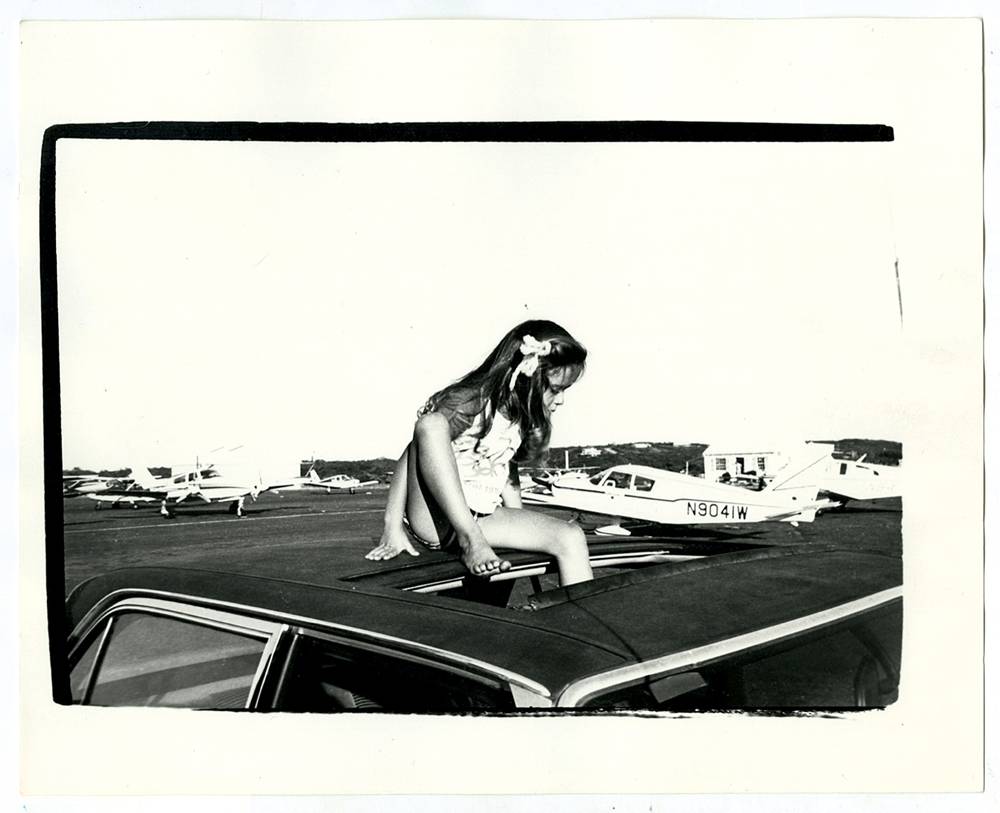

Dans l’introduction à cet ouvrage, Bob Colacello raconte les hasards qui firent de sa vie une odyssée délicieusement tiraillée entre l’avant-garde et la jet-set. “Il arriva tout simplement qu’aux fêtes que nous fréquentions à longueur de temps à New York, Los Angeles, Paris et Londres, les personnes les moins connues s’ingéniaient à se mettre dans le champ et à éclipser les plus connues, mais je prenais la photo quand même parce que je me rendais bien compte que, dans les fêtes, il est inévitable d’avoir un résultat comme ça, fait de couches superposées, que j’ai alors commencé à envisager comme mon propre style. Il arriva tout simplement que les seventies furent la décennie qui témoigna de la plus grande ouverture aux autres depuis les Années folles, et que chacun voulait en être – les jeunes et les vieux, les gays et les hétéros, les Noirs et les Blancs, les millionnaires et les escrocs –, l’illustration ultime de cette tendance ayant été atteinte dans la décadente boîte de nuit Studio 54.”

La ruse littéraire qui consiste à reprendre “It just happened” (“il arriva tout simplement”) me fait penser au “And just like that” qui revient à chaque épisode de la suite de Sex and the City vingt ans après, et qui présente Carrie Bradshaw aux prises avec une époque dont elle trouve les aspirations désolantes et rocambolesques (la scène où elle tombe des nues parce que son prétendant lui demande la permission de l’embrasser, par exemple), et qui lui fait regretter celle de sa jeunesse. Colacello semble pareillement nostalgique de cette époque “où l’on piquait juste votre portefeuille sans hacker votre compte en banque”, comme il le déclarait récemment au journal Le Monde.

Des photographies témoignant d’une époque de grande liberté

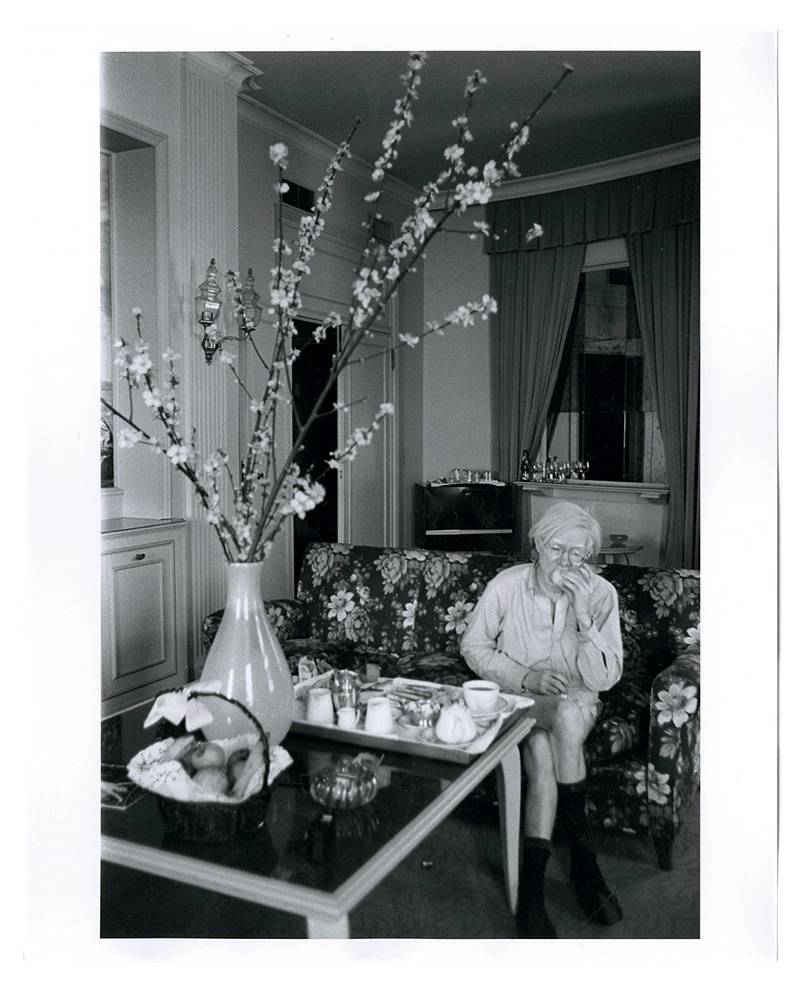

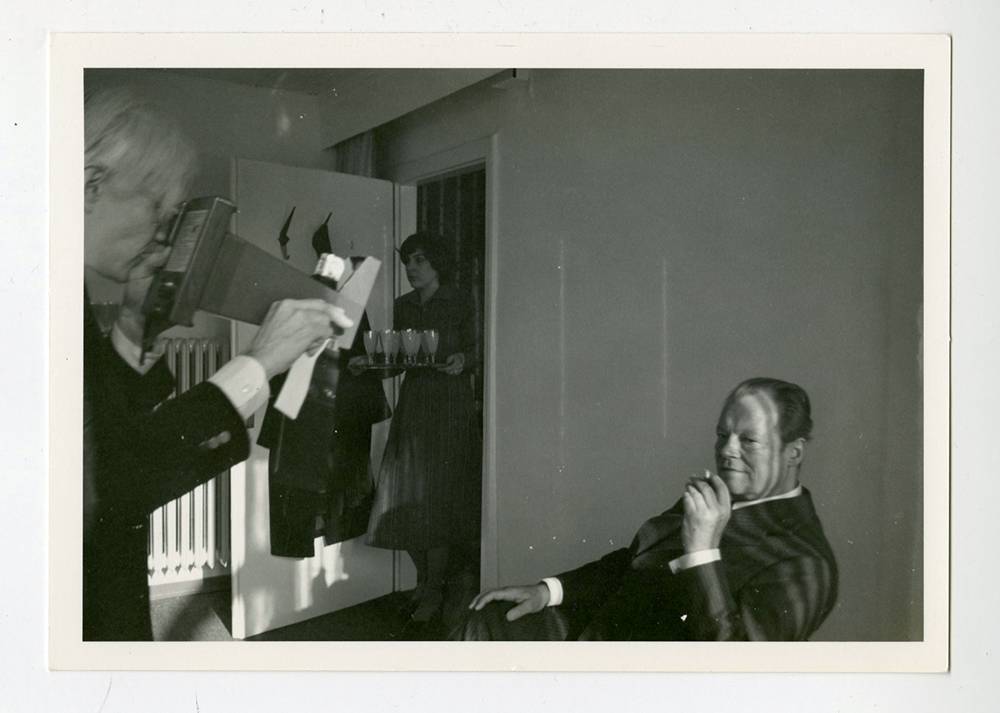

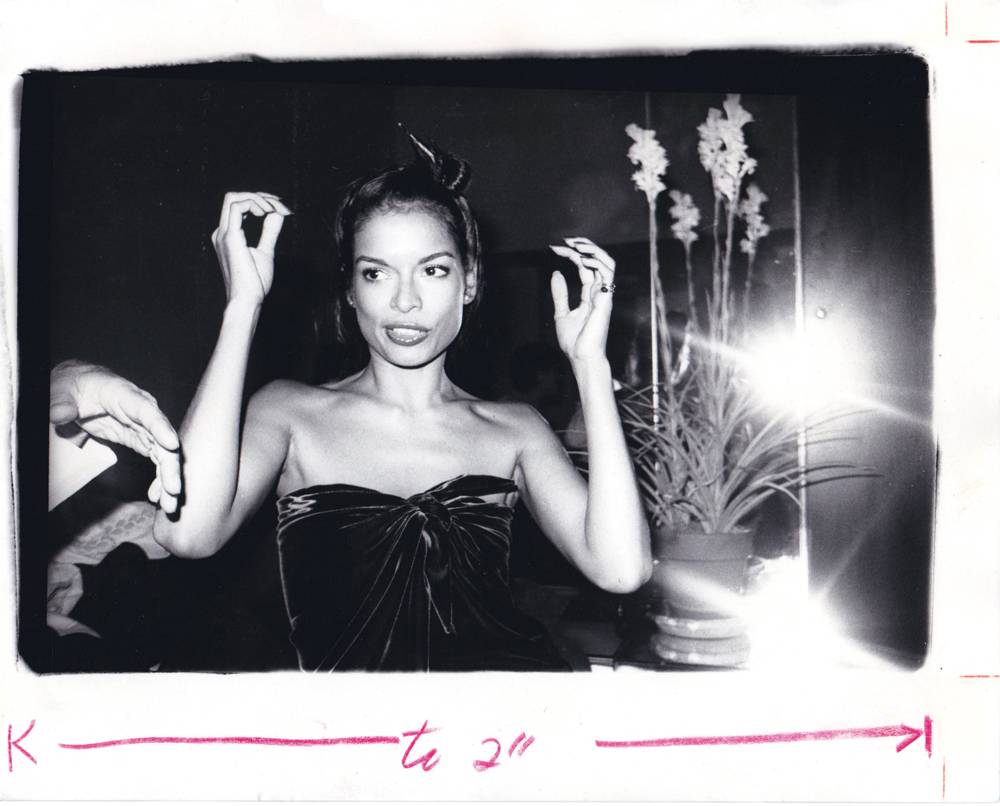

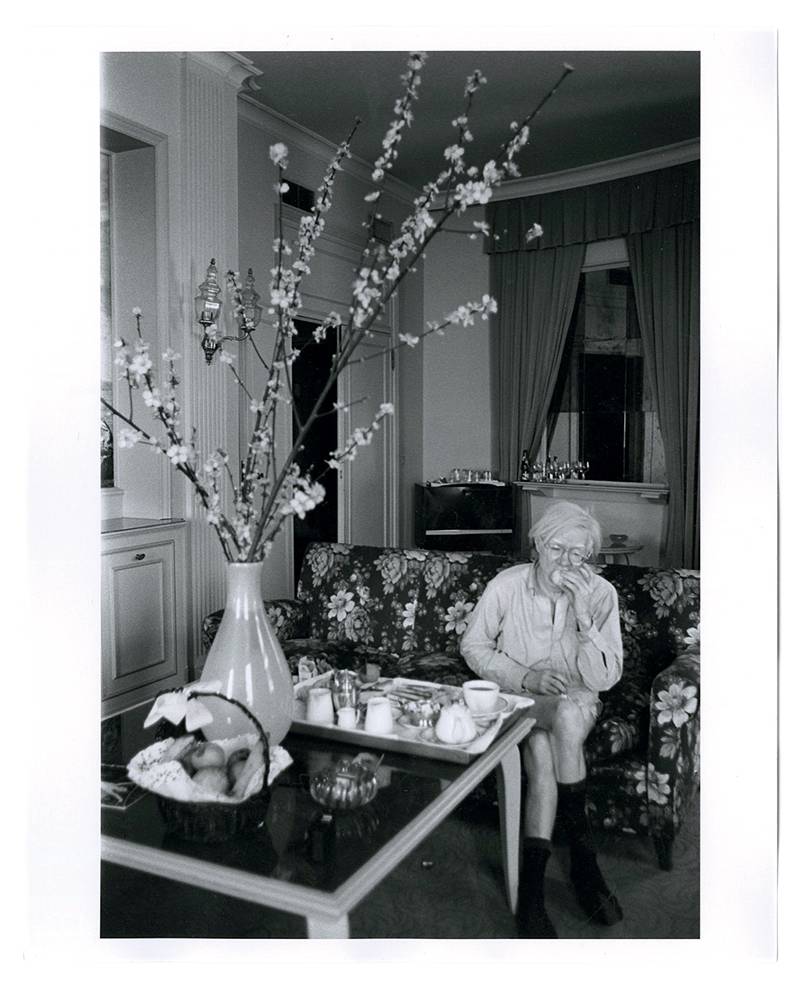

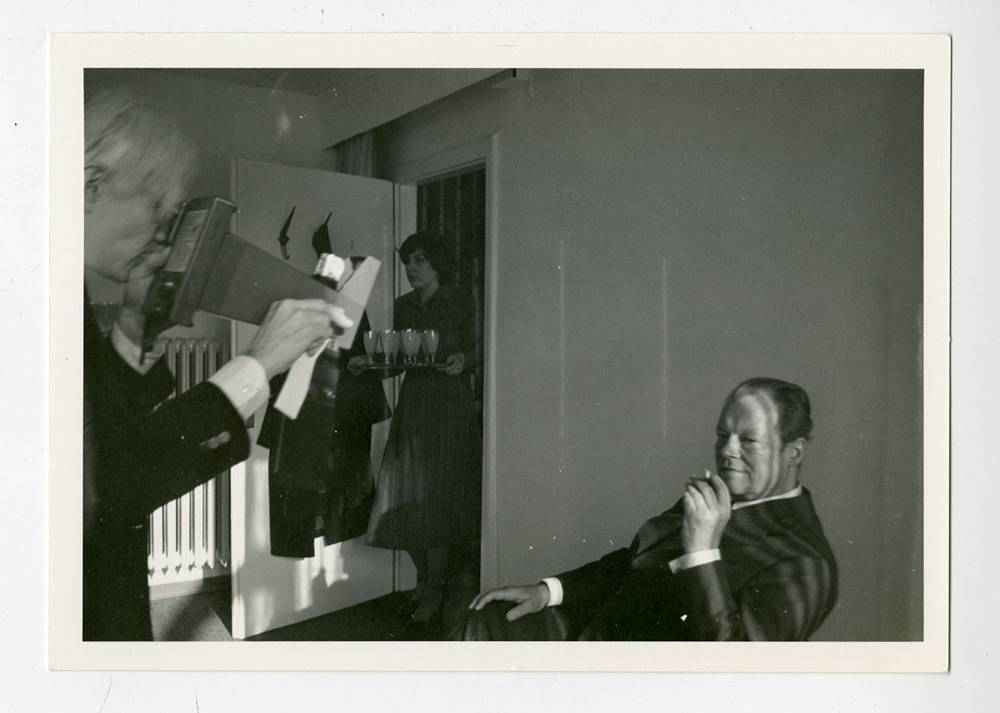

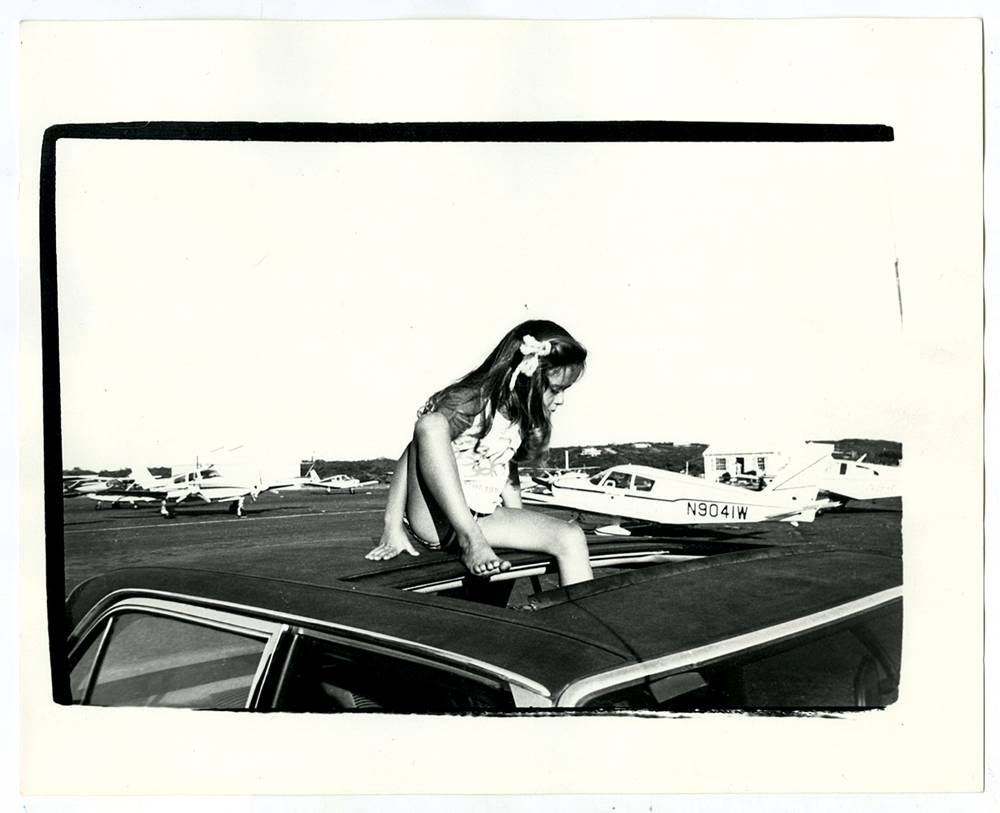

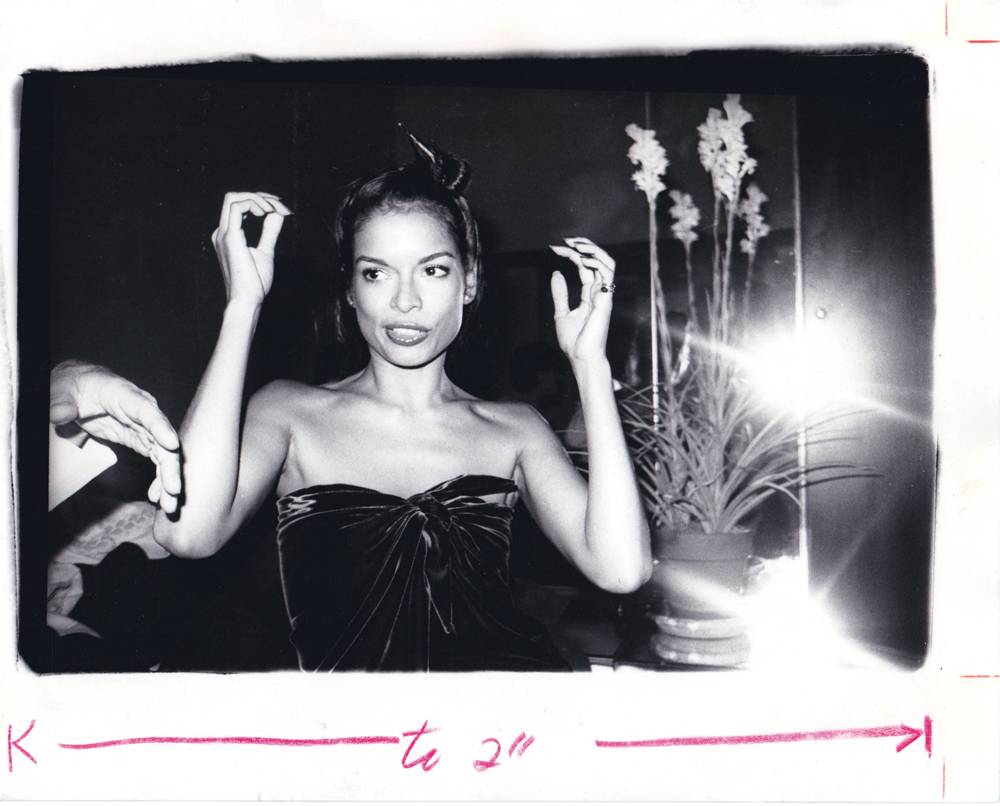

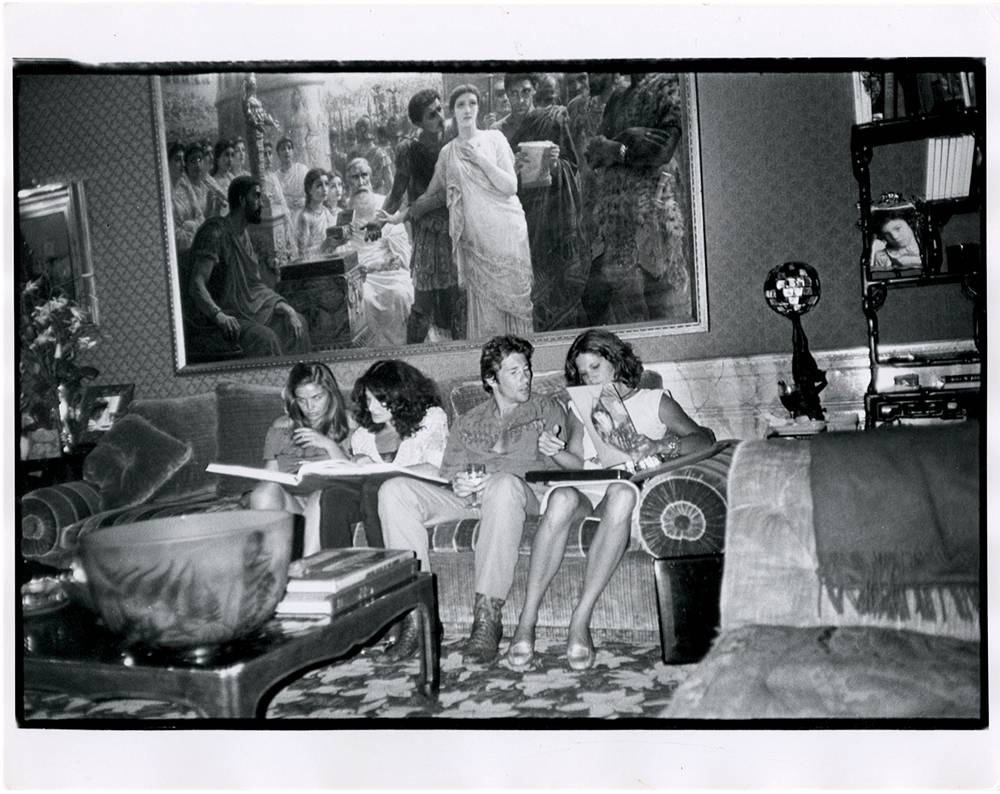

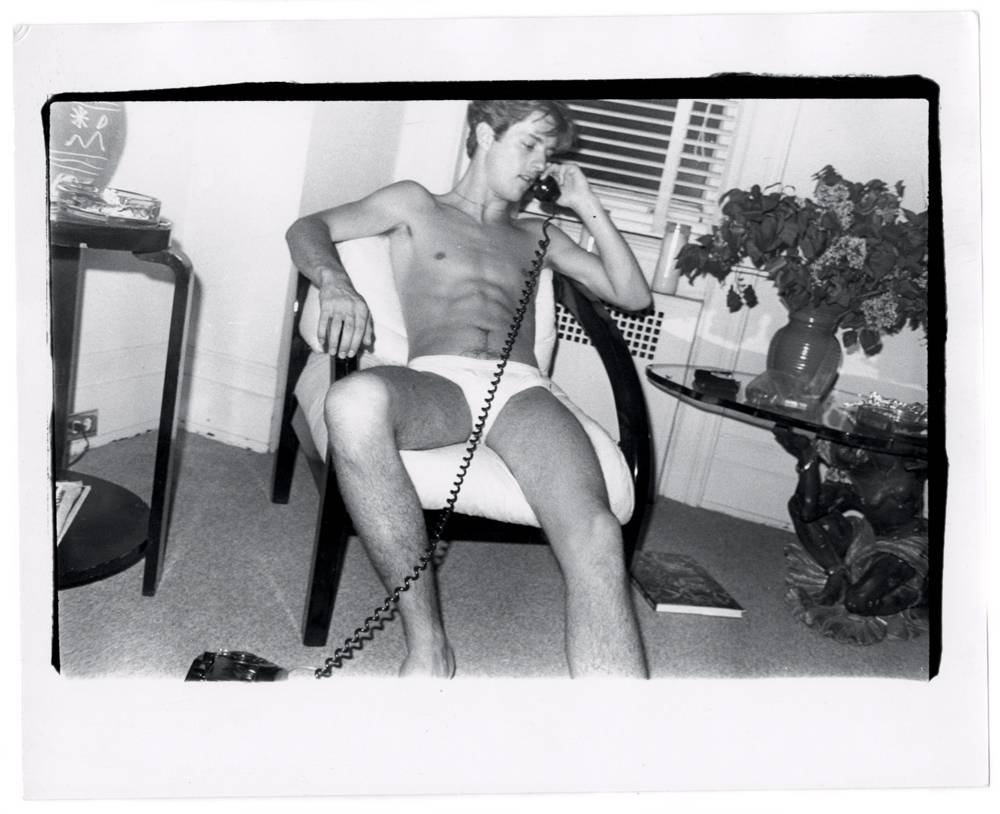

Ainsi sont les photographies de Colacello, qui dépeignent en effet une époque caractérisée par une fantaisie et une liberté dont les générations suivantes ont pensé qu’il était bon de s’affranchir pour s’infliger tout un tas de règles au nom du politically correct. On y découvre un panthéon d’individus hauts en couleur dont le noir et blanc exacerbe la dimension de document historique : Andy Warhol, bien sûr, dans beaucoup de situations domestiques, mangeant, par exemple, à même une assiette posée sur ses genoux – une photographie à laquelle Colacello ajoute une légende manuscrite : “Andy en train de manger, un magnétophone sur les genoux. Il l’appelait ‘ma femme Sony’.” Mais aussi Christina Onassis, Paloma Picasso, Jacqueline Bisset, Rudolf Noureïev, Estée Lauder, Norman Mailer, Truman Capote… L’auteur de Petit dejeuner chez Tiffany est par exemple photographié avec Warhol lors d’une séance de signature : “Après avoir été banni de la haute société, Truman commença à écrire pour Interview, et fit des séances de dédicace du magazine avec Andy, ici, dans une librairie de Southampton”, indique la légende rédigée par Bob Colacello.

Comme la plupart de ses photographies, celle-ci est un peu floue, sommairement cadrée, les personnages ne posent pas et sont saisis dans un instant, comme si la vie défilait à toute vitesse et que l’objectif en saisissait une seconde aléatoire. Mais parce que c’était lui derrière l’objectif, et que son carnet d’adresses était sans limites, les personnages photographiés dégagent un sentiment d’intimité. Y compris l’artiste allemand Joseph Beuys, que l’on voit à la galerie Lucio Amelio, à Naples, en 1980, en compagnie de Warhol, assorti de la légende : “Il n’était pas évident que Beuys apprécie qu’Andy encourage sa fille adolescente à devenir mannequin lorsqu’ils se retrouvèrent à Düsseldorf l’année suivante.” Le style “par défaut” de ces photographies semble avoir trouvé un écho quelques décennies plus tard dans la photographie de mode et, pour tout dire, la fascination qu’elle inspirent n’est pas étrangère à leur statut tout aussi bancal que, parfois, leur cadrage. Ce ne sont assurément pas des œuvres d’art, ce sont un peu des documents, un peu un journal intime, un peu du reportage et un peu des reliques historiques…

Le plus efficace portrait de Bob Colacello, me semble-t-il, est celui rédigé par Pat Hackett dans l’introduction au célébrissime Journal d’Andy Warhol dont, en tant que son “amie et collaboratrice de toujours”, elle établit l’édition à partir des appels téléphoniques quotidiens qu’elle avait avec lui. “Bob Colaciello, diplômé de l’école des services diplomatique et consulaire de l’université Georgetown, qui était entré à la Factory après avoir écrit une critique de Trash pour le Village Voice, travaillait alors principalement pour le magazine (qui s’intitulait désormais, son titre ayant subi une légère modification, Andy Warhol’s Interview) : il écrivait des articles, notamment sa chronique ‘Out’, sorte de journal de sa propre vie mondaine qui l’occupait jour et nuit, prétexte à citer le plus de noms possible chaque mois. En 1974, Bob Colacello (il avait alors supprimé le ‘i’) devint officiellement le rédacteur en chef du magazine : il lui donna son image conservatrice et androgyne. (Ce n’était pas un magazine pour la famille – une enquête réalisée à la fin des années 70 avait conclu que ‘le lecteur moyen d’Interview avait environ 0,0001 enfant.’) Sa politique éditoriale et publicitaire était élitiste à un point tel qu’elle se vouait – ainsi que Bob lui-même l’avait expliqué un jour en riant – à la restauration des dictatures et des monarchies les plus séduisantes du monde et les plus oubliées.”

Une exposition à la galerie Ropac qui raconte son amitié avec Andy Warhol

Les photographies de Colacello présentées dans l’exposition documentent essentiellement la période durant laquelle il fut aux côtés d’Andy Warhol, jusqu’à ce jour de 1983, le 6 janvier, dont Warhol fait le récit dans son Journal : “Quand je suis arrivé au bureau, Vincent m’a donné une lettre. Elle était de Bob. Il démissionne. […] Je suis content pour Bob. […] À propos du départ de Bob, ce n’est pas pour l’argent, il en gagnait beaucoup […] S’il a trouvé un nouveau travail, je suis content pour lui. Seulement, il n’aurait pas dû démissionner sans préavis. C’est moche. Ce n’est pas professionnel.” Quarante ans plus tard, Colacello corrige : “On a tous bossé pour rien pour Andy.” Bon, la rupture était peut- être quand même due à une histoire d’argent, bien que Colacello explique aussi en 2014, dans le magazine Interview justement : “J’avais 35 ans, et il était temps d’aller de l’avant. J’étais fatigué d’Andy – qui était alors dans sa période ‘mannequin anorexique’ pour l’agence Zoli –, j’en avais assez des frasques et des intrigues de ses camarades de jeu. […] Donc, oui, c’était une mauvaise rupture, mais je me suis lentement réconcilié avec lui, parce que le fait d’avoir travaillé ensemble de façon si proche et si productive avait créé énormément d’affection et de souvenirs communs.” La même année, Colacello partit travailler pour Vanity Fair.

Ses photographies ont assurément une inestimable valeur documentaire : c’est toute une époque qui s’y montre, et ce qui la différencie de l’époque actuelle s’expose à nous de façon cruelle. Elles sont aussi une passionnante biographie d’un homme qui, avec ses “It just happened”, prétend que le hasard joua un rôle primordial dans sa destinée. “Voilà, nous y sommes. Je n’ai jamais programmé ni intrigué pour en arriver là, écrit-il. Cependant j’ai toujours suivi ce dicton maternel : ‘Quand la chance frappe, ouvre la porte !’ Il y a eu pas mal de portes.”

Bob Colacello, “It Just Happened, Photographs (1976-1982)” jusqu’au 4 mars 2023 à la galerie Thaddaeus Ropac, Paris.

Born in Brooklyn in 1947, and raised on Long Island, he currently works for the Peter Marino Art Foundation in the Hamptons. His liv- ing-legend status doesn’t entirely depend on the 2004 book he published on Ronald and Nancy Reagan (“Half the art world stopped talking to me,” he recalls, though that hasn’t put him off planning to write the second volume soon) but rather on the time he spent with Andy Warhol in the 1970s – time he frenetically documented with his camera, a little Minox he always carried with him. Eighty of his photos, shot between 1976 and 1982, are currently on show at Thaddaeus Ropac in Paris (Marais), while a book of them has just come out titled It Just Happened.

Bob Colacello, photographer of jet set’s golden age

In his introduction, Bob Colacello recalls the accidents of life that turned his existence into a delicious back-and-forth between the avant- garde and the jet-set. “It just happened that at the parties we were constantly going to in New York, Los Angeles, Paris, and London, lesser-known people kept blocking my view of better-known people, but I took the pictures anyway, because I realized parties were like that, producing a layered look that I came to see as my style. It just happened that the 1970s was the most wide-open decade since the Roaring Twenties, and everyone wanted to be in the mix – young and old, gays and straights, blacks and whites, millionaires and hustlers – culminating in the ultimate decadent disco, Studio 54.”

The literary conceit of repeating “It just happened” makes me think of the “And just like that” in each episode of the Sex and the City reprise, which, 20 years later, shows Carrie Bradshaw struggling with an era whose aspirations she finds dismal and bizarre (for example, the scene where she’s astonished that her lover asks permission to kiss her) and that make her miss her youth. Colacello seems similarly regretful with respect to his own youth “when they just stole your wallet without hacking your bank account,” as he recently told Le Monde.

Photographs showcasing an era of freedom

His photos also now appear in a nostalgic light, portraying as they do an era whose liberty and flamboyance seem to have made the generations that followed want to free themselves from them by imposing all sorts of rules in the name of the politically correct. In Colacello’s candid shots, we find a whole host of larger-than-life figures recorded in a black and white that exaggerates their character as historical documents: Warhol, of course, often at home, for example eating from a plate on his lap, a photo to which Colacello added the hand-written caption: “Andy eating, tape recorder on his lap. He called it ‘My wife, Sony.’” But we also see, among other luminaries of the time, Christina Onassis, Paloma Picasso, Jacqueline Bisset, Rudolf Nureyev, Estée Lauder, Norman Mailer, and Truman Capote. The author of Breakfast at Tiffany’s was shot, among others, with Warhol during a bookstore signing: “After he was banned from international society, Truman started writing for Interview, and would sign copies of the magazine with Andy, here at a bookstore in Southampton,” reads Colacello’s caption.

Like most of his photos, this one is a bit blurry and perfunctorily composed: the subjects are not posing but captured in the instant, as though life was hurtling by at top speed and the shutter caught a random nanosecond. But because it was him be- hind the viewfinder, and because he had access to everybody, the subjects photographed have an air of intimacy, including the German artist Joseph Beuys, shot at the Lucio Amelio Gallery in Naples, in 1980, with Warhol. The caption reads, “It wasn’t clear if Beuys appreciated Andy encouraging his teenage daughter to become a model, when they met again in Düsseldorf the following year.”

The “default” style of his photos seems to have found an echo decades later in fashion photography and, in truth, their fascination is not entirely divorced from their uncertain status, which is just as lopsided as their on-the-hoof composition. While they’re certainly not artworks, they could be considered to a certain ex- tent historical documents, as well as diary entries, reportage, and also vestiges and relics. This indeterminate status also portrays a bygone age that has been replaced by one where it seems that everything must be defined, outlined, and circumscribed within its ambitions – ambitions that are easy to understand and, consequently, to consume.

The most effective portrait of Colacello is, to my mind, that written by Pat Hackett in the introduction to Warhol’s famous diary, which, as his “friend and long-time collaborator,” she edited, in light of her daily phone conversations with him. “Bob Colacello, who had graduated from Georgetown University’s School of Foreign Service and had come to the Factory by way of writing a review of Trash for the Village Voice, was working by this time mainly for the magazine (now, with a slight title change, called Andy Warhol’s Interview), doing articles and writing his column, OUT, which chronicled his own around-the-clock social life and dropped a heavy load of names every month. In 1974 Bob Colacello (by then he’d dropped the “i”) officially became the magazine’s executive editor, shaping its image into a politically conservative and sexually androgynous one. (It wasn’t a magazine with a family readership – one survey in the late 70s concluded that the ‘average Interview reader had something like .001 children.’) Its editorial and advertising policies were elitist to the point of being dedicated – as Bob himself once explained, laughing – to ‘the restoration of the world’s most glamorous – and most forgotten – dictatorships and monarchies.’ It was a goal, people pointed out, that seemed incongruous with Bob’s Brooklyn accent, but this didn’t stop him from going on to specify exactly which monarchies he missed most and why.”

His friendship with Andy Warhol at the core of an exhibition

The Colacello photos shown in the exhibition essentially document his time with Warhol, until that fateful day of 6 January 1983, which Warhol recorded in his diary: “When I got to the office, Vincent gave me a letter. It was from Bob. He had resigned … I was happy for Bob. … With respect to Bob’s departure, it wasn’t be- cause of the money, he earned a lot … If he’s found a good job, I’m happy for him. Only he shouldn’t have re- signed without notice. That’s not nice. And it’s not professional.” Forty years later, Colacello corrected, “We all worked for Andy for nothing.” So the breakup was perhaps a question of money after all, even though Colacello also explained, in 2014, ironically in Interview: “I was 35, and it was time to move on. I was tired of Andy – then in his anorexic Zoli model phase – fed up with the antics and intrigues of his playmates … So, yes, it was a bad breakup, but I slowly reconciled, because there was a deep reservoir of shared experience and affection from working together so closely for so long and so productively.” That same year, Colacello began collaborating with the magazine Vanity Fair.

His photos have an undeniable documentary value, since a whole era is captured in them, and the way it differs from the times we’re living in today becomes cruelly clear as we peruse them. They are also a fascinating biography of a man who, with his “It just happened,” claims that chance played a primordial role in his destiny. “So here we are. I never planned or plotted any of this,” he writes. “I have, however, always fol- lowed my mother’s dictum: ‘When opportunity knocks, open the door!’ I’ve walked through a lot of doors.”

Bob Colacello’s exhibition “It Just Happened, Photographs 1976–82” is currently on view at the Thaddaeus Ropac Gallery, Paris Marais, until 4 March 2023.