21

21

Trevor Paglen: spy on the live visitors of his new exhibition

Le 10 septembre dernier, Trevor Paglen ouvrait les portes de sa nouvelle exposition dans l’espace de la Pace Gallery à Londres. Une fois de plus, l’artiste américain y présente des œuvres qui mettent en exergue les dangers de l’intelligence artificielle mais imagine également d’un dispositif inédit, inspiré par les mutations technologiques à l’heure du confinement : les visiteurs virtuels peuvent s’y infiltrer à l’aide de multiples caméras ainsi qu’à y projeter leur propre image sur des écrans. Numéro s’est entretenu avec l’artiste à cette occasion.

Interview by Matthieu Jacquet.

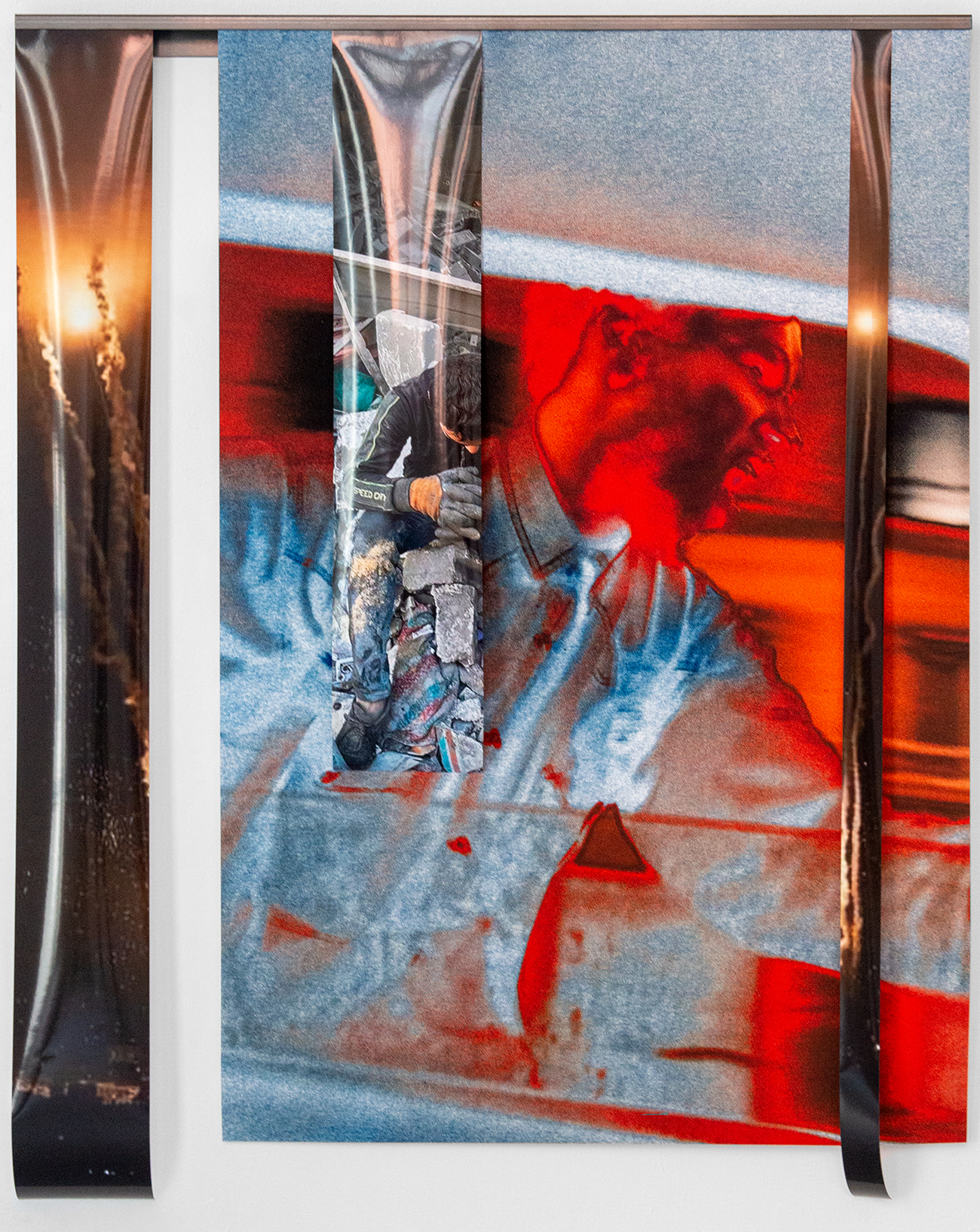

This year more than ever, virtual technology is on everybody’s mind and the art world did not take long to partake in it. In a post-quarantine era, the museums, galleries, artists, foundations and other cultural venues – from the edgiest to the most sceptical ones – all went along for the ride to try and compensate the lack of physical exhibitions, as the working world was multiplying conference calls on Zoom and Skype. Years ago, Trevor Paglen had already anticipated this mutation of expression and communication devices by displaying through his work a critical gaze on the new technologies that make up their principal material. From his drone shots of the sky to his photographs of submarine cables networks, the American artist has always tried to make visible the powerful and invisible machines that observe and rule our world, as a way to alert on mass surveillance as well as on the intrusion of capitalism in our lives’ most private spaces.

During two months, Trevor Paglen will be presenting his latest works at the Pace Gallery in London. The collection includes IA coloured flowers made during quarantine while he was in New York. Very observing of the latest evolutions of online art, the artist integrated in the physical exhibition a device made for the web that allows – thanks to multiple cameras – the internet users to experience Paglen’s work at the same time as the live visitors. The remote visitor then becomes a sort of Big Brother, an omniscient spy that rules and controls the security cameras and whose image can also – if desired – be projected onto the walls of the gallery. As a way to come back to this ambitious project that is particularly relevant to these unprecedented times, Numéro had a discussion with Trevor Paglen on Zoom – quite ironically –, a platform against which the artist does not hesitate to express his scepticism

Numéro : How is it to plan a solo exhibition in a post-Covid-19 era?

It was a very difficult show to put together for different reasons. On one hand, it was difficult logistically, because everybody I would normally work with – fabric makers, printers – I could not : I was in New York most of the time and had to work remotely, which was really hard. More importantly, it was also really difficult to work in an environment where the meanings of things all around you are changing so much and so tremendously, being so much more powerful than you are as an artist. Things that you haven’t thought twice about before now have a different significance : airplanes in the sky, the keypad, the credit card readers, the subway, the handle of a gas pump… As an artist, you’re usually able to feel like you can take an image and change its meaning a little bit, but in an environment like this it all feels like you are a surfer and you are trying to paddle through a thousand feet high wave, and you have no chance. These bigger forces are at work in terms of determining what you are. So many giant powers are shaping things that you have to try to work within this, and pay attention to them.

This year more than ever, virtual technology is on everybody’s mind and the art world did not take long to partake in it. In a post-quarantine era, the museums, galleries, artists, foundations and other cultural venues – from the edgiest to the most sceptical ones – all went along for the ride to try and compensate the lack of physical exhibitions, as the working world was multiplying conference calls on Zoom and Skype. Years ago, Trevor Paglen had already anticipated this mutation of expression and communication devices by displaying through his work a critical gaze on the new technologies that make up their principal material. From his drone shots of the sky to his photographs of submarine cables networks, the American artist has always tried to make visible the powerful and invisible machines that observe and rule our world, as a way to alert on mass surveillance as well as on the intrusion of capitalism in our lives’ most private spaces.

During two months, Trevor Paglen will be presenting his latest works at the Pace Gallery in London. The collection includes IA coloured flowers made during quarantine while he was in New York. Very observing of the latest evolutions of online art, the artist integrated in the physical exhibition a device made for the web that allows – thanks to multiple cameras – the internet users to experience Paglen’s work at the same time as the live visitors. The remote visitor then becomes a sort of Big Brother, an omniscient spy that rules and controls the security cameras and whose image can also – if desired – be projected onto the walls of the gallery. As a way to come back to this ambitious project that is particularly relevant to these unprecedented times, Numéro had a discussion with Trevor Paglen on Zoom – quite ironically –, a platform against which the artist does not hesitate to express his scepticism

Numéro : How is it to plan a solo exhibition in a post-Covid-19 era?

It was a very difficult show to put together for different reasons. On one hand, it was difficult logistically, because everybody I would normally work with – fabric makers, printers – I could not : I was in New York most of the time and had to work remotely, which was really hard. More importantly, it was also really difficult to work in an environment where the meanings of things all around you are changing so much and so tremendously, being so much more powerful than you are as an artist. Things that you haven’t thought twice about before now have a different significance : airplanes in the sky, the keypad, the credit card readers, the subway, the handle of a gas pump… As an artist, you’re usually able to feel like you can take an image and change its meaning a little bit, but in an environment like this it all feels like you are a surfer and you are trying to paddle through a thousand feet high wave, and you have no chance. These bigger forces are at work in terms of determining what you are. So many giant powers are shaping things that you have to try to work within this, and pay attention to them.

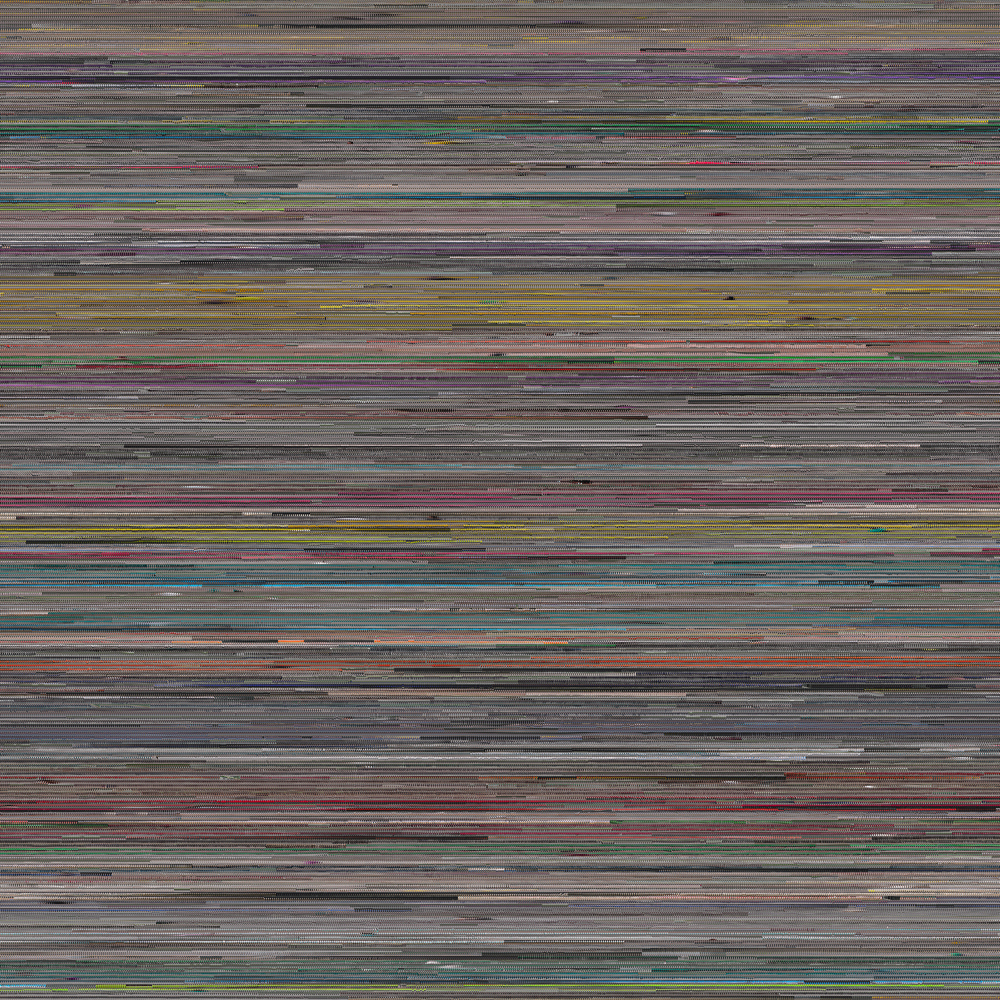

In a lot of your recent works, flowers has become the main subject, which creates a very striking contrast between the usual delicacy and romanticism of depicting flowers and the very frightening consequences of AI in the colours and shapes of the photographs. Was it the reason that led you to choose such subjects?

If you had told me, even last year, that I would make an exhibition about flowers I would have thought you were out of your mind. Some of the central works in the exhibition are extremely detailed photographs of flowers, more specifically blooms on trees. After being photographed, they are being analyzed by a software that we created and colors are being attributed to the different parts of the image, based on what the AI thinks the different objects are. So those colors are arbitrary. The idea was to bring together these real tensions between the natural world and this very predatory AI systems and technology platforms that we all find ourselves embedded with, to a much greater extent than we want to be. These flowers can both represent being born and blooming, but also dying, becoming more fragile. Being some of the biggest clichés in the history of art, these themes and symbols felt very compelling to me. Secretly, the show is also a reflection on Dürer’s Melancholia I, this famous engraving where we see an angel sitting among many science tools with art being scattered around. It hinges to a deep contemporary crisis of meaning.

“I always thought that being human does not end where one’s body ends.”

In your last interview for Numéro, you said that landscape has always been at the core of your work. Why do you think is that?

I have a funny answer to that : I think it is because I am from California, because I grew up in very broad environments. But it obviously is more complex than this : I have been always been more invested in the landscape tradition, as I am always interested in how humans change the landscape, but also how we are in turn changed by the ways we changed landscapes I always thought that being human does not end where one’s body ends.

In a lot of your recent works, flowers has become the main subject, which creates a very striking contrast between the usual delicacy and romanticism of depicting flowers and the very frightening consequences of AI in the colours and shapes of the photographs. Was it the reason that led you to choose such subjects?

If you had told me, even last year, that I would make an exhibition about flowers I would have thought you were out of your mind. Some of the central works in the exhibition are extremely detailed photographs of flowers, more specifically blooms on trees. After being photographed, they are being analyzed by a software that we created and colors are being attributed to the different parts of the image, based on what the AI thinks the different objects are. So those colors are arbitrary. The idea was to bring together these real tensions between the natural world and this very predatory AI systems and technology platforms that we all find ourselves embedded with, to a much greater extent than we want to be. These flowers can both represent being born and blooming, but also dying, becoming more fragile. Being some of the biggest clichés in the history of art, these themes and symbols felt very compelling to me. Secretly, the show is also a reflection on Dürer’s Melancholia I, this famous engraving where we see an angel sitting among many science tools with art being scattered around. It hinges to a deep contemporary crisis of meaning.

“I always thought that being human does not end where one’s body ends.”

In your last interview for Numéro, you said that landscape has always been at the core of your work. Why do you think is that?

I have a funny answer to that : I think it is because I am from California, because I grew up in very broad environments. But it obviously is more complex than this : I have been always been more invested in the landscape tradition, as I am always interested in how humans change the landscape, but also how we are in turn changed by the ways we changed landscapes I always thought that being human does not end where one’s body ends.

These past months, we’ve seen many digital and virtual initiatives, online programmes, interactive exhibitions… From someone like you, whose work particularly revolves around the insidious control and intrusion of technology and the virtual world into our personal lives, what could be the dangers of these new formats?

I am sure you’ve seen the scandals about algorithms doing all the grading for tests at universities and high schools and how terrible they were, because they can’t actually interpret new answers and read like a human would read. Some similar things have happened in the world, like algorithms designed to detect whether you are paying attention or what kind of mood you are in, if you are positive or negative. Those are increasingly becoming tools that are used on apps like Zoom to monitor people who are working remotely. There are million reasons to worry about it, but the overall question has to do with their colonization of parts of our everyday life by capital and police in places where it was not possible before. Today, companies are trying to extract money from us now in those very personal spaces, while police is watching over us. We are seeing the expense of those forms of power in spaces of self representation where we used to do things without consequences.

Your exhibition at Pace Gallery is a direct response to the recent shift in our ways of expressing ourselves and interacting during lockdown. How did virtual platforms such as Zoom inspired you?

One of the challenges was making a show that very few people would be able to finally see in person. We used to assume that people would travel to the city to see it, but it is not that true anymore. So instead of conceiving an usual physical show and then documenting it online, I thought about making an exhibition that you could see in one way physically, and the online way of visiting it would be completely different from seeing it in person. For that, we built a system called “Octopus” : throughout the show there are tripods of cameras and cables all inside the gallery coming from the ceiling, and we are streaming the live videos they are taking on the gallery’s website as well as the security cameras images. The users will be able to click on these different cameras and look at the show through their eyes but can also, if they agree to it, steam their image inside the screens of the exhibition. Visitors will then see people looking down on them walking through the show. For me, this new project was a way to play with these forms of sociability and viewing that we have been forced into being quarantined, enhancing their aesthetics but also the unease we feel when we understand all the sorts of power dynamics built in those systems.

“I use contemporary technology because to understand how to see the world now.”

Why did you name this new system “Octopus”?

That’s a good question. It was originally an internal name that we were using, while trying to think of a more appropriate way to name it. The origins of the name are very obscure : it comes from a uniform patch of a spy satellite, that I have been collecting for years, where we can see an octopus and the sentence “Nothing is beyond our reach”. It’s a very precise reference but it actually makes sense. I was also thinking of all the cables and cameras as like tentacles coming out here, all those infrastructures that work remotely but of course are not neutral.

These past months, we’ve seen many digital and virtual initiatives, online programmes, interactive exhibitions… From someone like you, whose work particularly revolves around the insidious control and intrusion of technology and the virtual world into our personal lives, what could be the dangers of these new formats?

I am sure you’ve seen the scandals about algorithms doing all the grading for tests at universities and high schools and how terrible they were, because they can’t actually interpret new answers and read like a human would read. Some similar things have happened in the world, like algorithms designed to detect whether you are paying attention or what kind of mood you are in, if you are positive or negative. Those are increasingly becoming tools that are used on apps like Zoom to monitor people who are working remotely. There are million reasons to worry about it, but the overall question has to do with their colonization of parts of our everyday life by capital and police in places where it was not possible before. Today, companies are trying to extract money from us now in those very personal spaces, while police is watching over us. We are seeing the expense of those forms of power in spaces of self representation where we used to do things without consequences.

Your exhibition at Pace Gallery is a direct response to the recent shift in our ways of expressing ourselves and interacting during lockdown. How did virtual platforms such as Zoom inspired you?

One of the challenges was making a show that very few people would be able to finally see in person. We used to assume that people would travel to the city to see it, but it is not that true anymore. So instead of conceiving an usual physical show and then documenting it online, I thought about making an exhibition that you could see in one way physically, and the online way of visiting it would be completely different from seeing it in person. For that, we built a system called “Octopus” : throughout the show there are tripods of cameras and cables all inside the gallery coming from the ceiling, and we are streaming the live videos they are taking on the gallery’s website as well as the security cameras images. The users will be able to click on these different cameras and look at the show through their eyes but can also, if they agree to it, steam their image inside the screens of the exhibition. Visitors will then see people looking down on them walking through the show. For me, this new project was a way to play with these forms of sociability and viewing that we have been forced into being quarantined, enhancing their aesthetics but also the unease we feel when we understand all the sorts of power dynamics built in those systems.

“I use contemporary technology because to understand how to see the world now.”

Why did you name this new system “Octopus”?

That’s a good question. It was originally an internal name that we were using, while trying to think of a more appropriate way to name it. The origins of the name are very obscure : it comes from a uniform patch of a spy satellite, that I have been collecting for years, where we can see an octopus and the sentence “Nothing is beyond our reach”. It’s a very precise reference but it actually makes sense. I was also thinking of all the cables and cameras as like tentacles coming out here, all those infrastructures that work remotely but of course are not neutral.

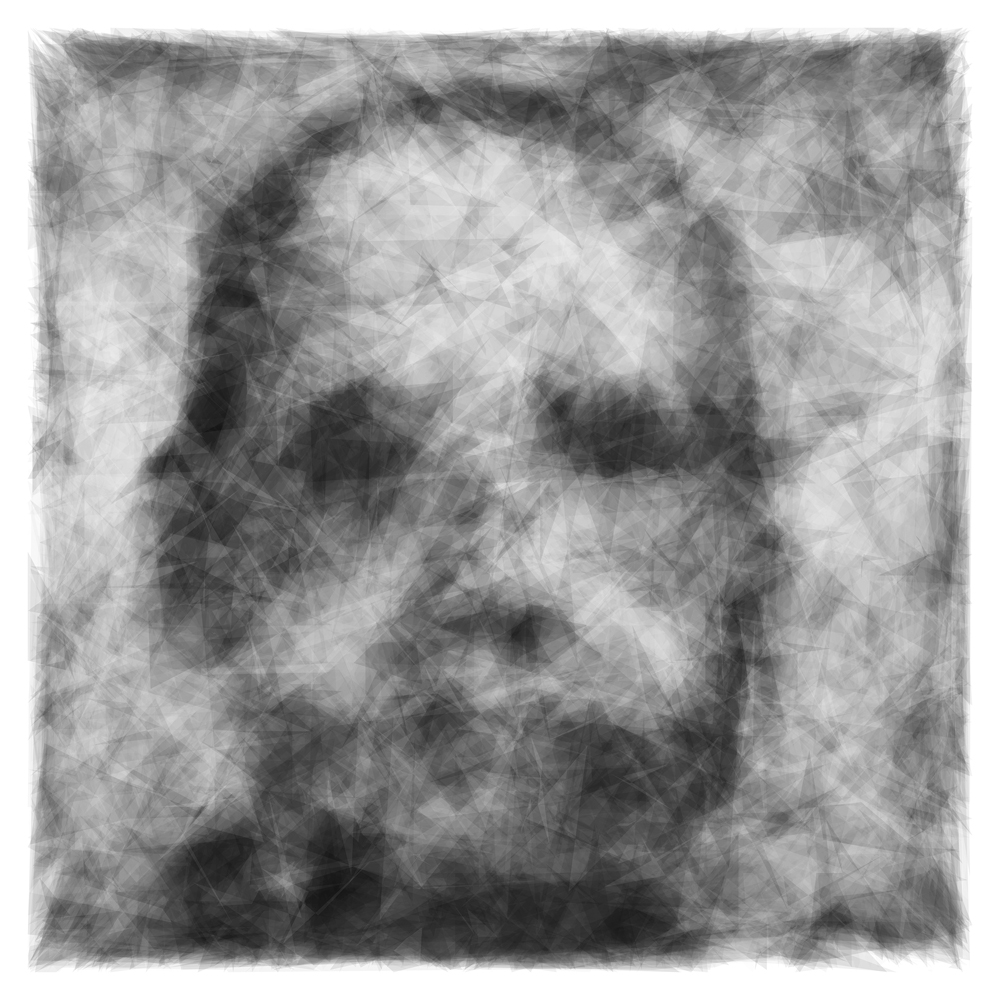

You said that “computer vision and artificial intelligence have become ubiquitous”, but somehow they also offer you the main material of a lot of your works. Do you see your relationship to contemporary technology as paradoxical?

No I do not actually. I do use these kinds of technology a lot, but it’s not at all because I love it, more so because I want to understand how to see the world now. To do that, you have to understand how the world is being seen by technological systems, machine learning systems, facial working systems, because today they are doing a huge amount of the seeing that is going on. It would be hard for me to imagine contemporary forms of seeing our society without taking them into account.

“If you had told me last year I would make an exhibition about flowers, I would have thought you were out of your mind.”

Do you think that today, one’s identity is technology’s prisoner?

Absolutely, because technology gathers the mechanisms that are available to us and the ways that we interact with each other are filtered through them. It’s not just about what we do but also what we do not do. A lot of us are working on platforms like Zoom, Skype, but they are very limited, there is a very specific form sociability that is kind of scripted inside the medium. An interview, a business meeting can be done there, but anything that is more whimsical or free is really hard as it feels like working. That is one of their consequences : so much of our intercommunications became organized over work. On the other hand, there’s no structure through which we can meet people that we do not know, which is not possible at all on these platforms. These are two examples of how the platforms we use to communicate shape sociability, and that is even before we get into the data collection, the ways in which the limited forms of sociability we have online are monetized or become means of policing, of value extraction. These are also very Western-centricc, ethnocentric and urban-centric concerns, as there are still many in places where people do not depend of these platforms as much as we do.

Your exhibition is entitled “Bloom”. What does this word mean to you?

I was very literally thinking about when I thought about the show. I was in my apartment which I could not leave, and the city outside was very empty. You could hear people on their phones from two blocks away, the streets signs creaking with the wind blowing, it was really crazy. At the same time, there was this bloom of Spring coming and all the plants bursting out with smell and colors, the contrast was unbelievable. So the title was about the bloom of the Spring in the absence of people, but also about what other things were allowed to bloom during that time, such as technology platforms like Zoom or huge retailers like Amazon, who were making billions of dollars everyday because there are maintaining infrastructures that people believe are even more essential today. I was also thinking about the blooming of fascism and terrorism, and the opportunities we have for imagining different and more equitable futures in a moment of crisis where the inequalities of the society are made so clear to see.

Trevor Paglen, Bloom, from September 10 to November 10 at Pace Gallery, London. Visit the online exhibition here.

You said that “computer vision and artificial intelligence have become ubiquitous”, but somehow they also offer you the main material of a lot of your works. Do you see your relationship to contemporary technology as paradoxical?

No I do not actually. I do use these kinds of technology a lot, but it’s not at all because I love it, more so because I want to understand how to see the world now. To do that, you have to understand how the world is being seen by technological systems, machine learning systems, facial working systems, because today they are doing a huge amount of the seeing that is going on. It would be hard for me to imagine contemporary forms of seeing our society without taking them into account.

“If you had told me last year I would make an exhibition about flowers, I would have thought you were out of your mind.”

Do you think that today, one’s identity is technology’s prisoner?

Absolutely, because technology gathers the mechanisms that are available to us and the ways that we interact with each other are filtered through them. It’s not just about what we do but also what we do not do. A lot of us are working on platforms like Zoom, Skype, but they are very limited, there is a very specific form sociability that is kind of scripted inside the medium. An interview, a business meeting can be done there, but anything that is more whimsical or free is really hard as it feels like working. That is one of their consequences : so much of our intercommunications became organized over work. On the other hand, there’s no structure through which we can meet people that we do not know, which is not possible at all on these platforms. These are two examples of how the platforms we use to communicate shape sociability, and that is even before we get into the data collection, the ways in which the limited forms of sociability we have online are monetized or become means of policing, of value extraction. These are also very Western-centricc, ethnocentric and urban-centric concerns, as there are still many in places where people do not depend of these platforms as much as we do.

Your exhibition is entitled “Bloom”. What does this word mean to you?

I was very literally thinking about when I thought about the show. I was in my apartment which I could not leave, and the city outside was very empty. You could hear people on their phones from two blocks away, the streets signs creaking with the wind blowing, it was really crazy. At the same time, there was this bloom of Spring coming and all the plants bursting out with smell and colors, the contrast was unbelievable. So the title was about the bloom of the Spring in the absence of people, but also about what other things were allowed to bloom during that time, such as technology platforms like Zoom or huge retailers like Amazon, who were making billions of dollars everyday because there are maintaining infrastructures that people believe are even more essential today. I was also thinking about the blooming of fascism and terrorism, and the opportunities we have for imagining different and more equitable futures in a moment of crisis where the inequalities of the society are made so clear to see.

Trevor Paglen, Bloom, from September 10 to November 10 at Pace Gallery, London. Visit the online exhibition here.