13

13

Why are painters John Currin and Carroll Dunham obsessed with the nude body?

American painters John Currin and Carroll Dunham both practise a no-holds-barred exploration of the pictorial possibilities of the male and the female nude, and both artists will be showing highly anticipated exhibitions of brand-new work this autumn.

By Éric Troncy.

One looks to science fiction, conceptual art and cartoon strips, the other references cartoons too – but pornographic this time – as well as Jan van Eyck, Lucas Cranach and 16th-century Italian Mannerist masters. Both are major figurative painters, and both are white, male and American. One is nearing 60 and the other is over 70. When they exhibit new work it is always a much-anticipated event, and both have solo shows coming up this autumn in major international galleries. And both are no doubt ready to face the fuss that will inevitably ensue from their choice of subject matter: women, and a lot of sex. Clearly old white men have nothing left to lose…

They sit at opposite ends of the spectrum of figurative painting. 71-year-old Carroll Dunham turned progressively towards figuration in the late 1970s – mouths started to appear in his abstract canvases, fol- lowed by biomorphic cartoon-like figures, then trees and finally female bathers and male wrestlers – but his work continues to claim conceptual ambitions. 59-year-old John Currin, on the other hand, has remained true to his beginnings, his oeuvre consisting in highly realist figurative painting inspired by the old masters, with a penchant for female subjects – but also sometimes male, as seen in his 2019 show My Life as a Man at Dallas Contemporary.

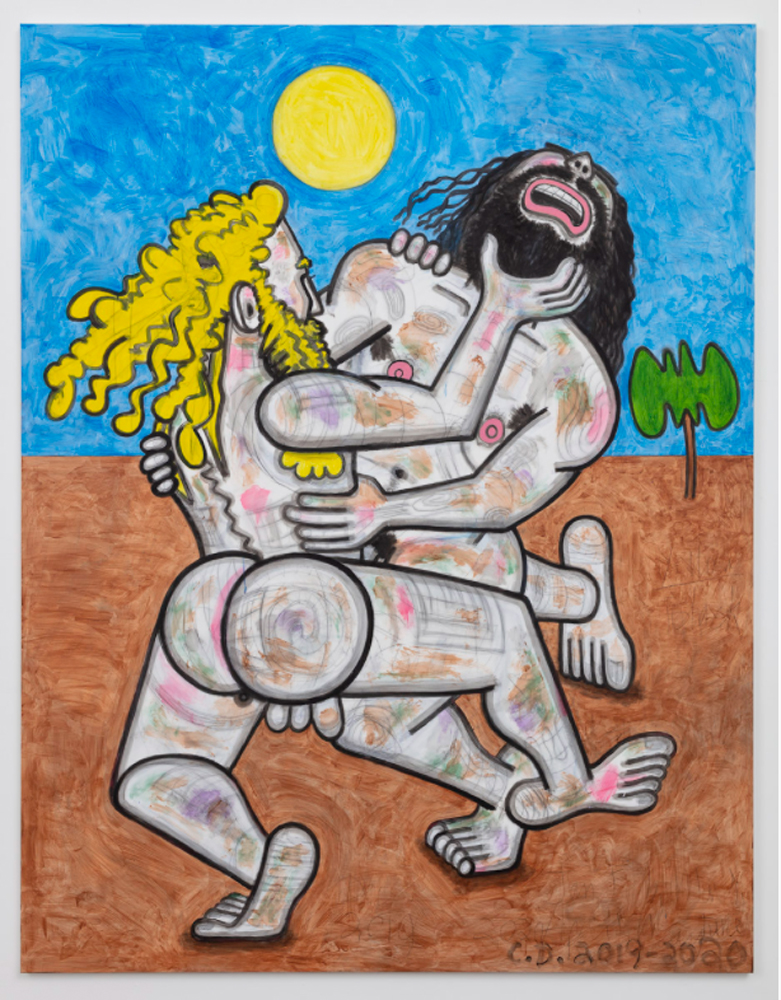

Born in 1949, in Connecticut – where he lives, as well as in New York –, Carroll Dunham makes paintings that are certainly figurative but not what you’d call realistic. Though human figures are the essential compositional component in his current work, they’re treated like forms in an abstract painting, offer- ing all sorts of combinations of out- line, depending on whether the arms are crossed or stretched out, the legs raised or in contact with the ground, the bodies standing or reclining, etc. And things become yet more complex when two figures interact, producing a whole catalogue of compositions that Dunham methodically explores.

At the time of writing we know nothing about the new series of paintings he’ll be showing in late October at the Eva Presenhuber Gallery in Zürich, but those he exhibited in June at the Max Hetzler Gallery in London (with Albert Oehlen), or in early 2021 at the Gladstone Gallery in New York, bear witness to this approach: each painting depicts two figures and explores the compositional permutations of their bodies combined in space. In New York, he showed a series of wrestlers, a theme he has been exploring for a number of years. “My gay friends always tell me, ‘You don’t paint wrestlers, what you draw are boys getting it on together,’” says Dunham. “Okay, I’m not upset by that interpretation, and yet it was clear to me that I was drawing men wrestling. But I knew once I was done with the wrestler paintings I wanted to make paintings of men and women having sex.”

He had already painted solo female figures (the bathers series), and pairs of masculine figures (the wrestlers series), but this is the first time he has tackled male/female couples. Shown in copulation, they offer as many compositional permutations as the Kama Sutra, and the use of colour is no longer confined to hair being blond or dark but extends to the bodies themselves, which are sometimes green – a choice that, as he explained, wasn’t only inspired by his admiration for Salvador Dalí (who was a major factor in his decision to become an artist) in particular and Surrealism in general. “The figures in my paintings were for a long time, seven or eight years, literally white, unpainted, a sort of void in the middle of the picture,” he recalled. “I started to think about other ways of differentiating the figures if I had to include several in the canvases. I’m a white man in the US, and I don’t want the subject of my work to be directly representative of a milieu. So I tried to come up with a way of using colour to differentiate the protagonists without immediately setting off a discussion about race, politics and other topics of that kind. I have a lot of personal ideas about those questions, but they’re not exactly the subject of my work. The other thing is that I’m very interested in the way the word ‘green’ seems to represent some- thing full of hope that looks toward the future. I’ve read a lot of science fiction in my life, and green men don’t shock anyone in that world. Even in James Cameron’s film Avatar you can see perfect humans with blue skin, and yet nobody talks about race.”

Born in 1962 in Colorado, John Currin, who now lives in New York, hit the headlines at the outset of his career, in 1989, with work that is both figurative and realist and does nothing to hide his fascination with the history of classical painting. “At a time when most of his contemporaries would cite Warhol, Duchamp and Nauman among their influences, Currin invokes Bruegel, Cranach and Parmigianino,” wrote critic and philosopher Arthur Danto in 2004. “The truth is I may be inspired by the face from a Botticelli painting, the torso from a Lucas Cranach or the legs from someone else,” Currin told the The Brooklyn Rail earlier this year. Twenty years ago he declared to Robert Rosenblum: “Don’t make so-called contemporary art. Be yourself. Give yourself the most pleasure. That’s the reason to be an artist. You don’t have a job. You don’t have to show up anywhere on time. It stands to reason that you can do anything you want to. It’s such an obvious point, but you’d be surprised at how many people don’t know that and make art for somebody else.”

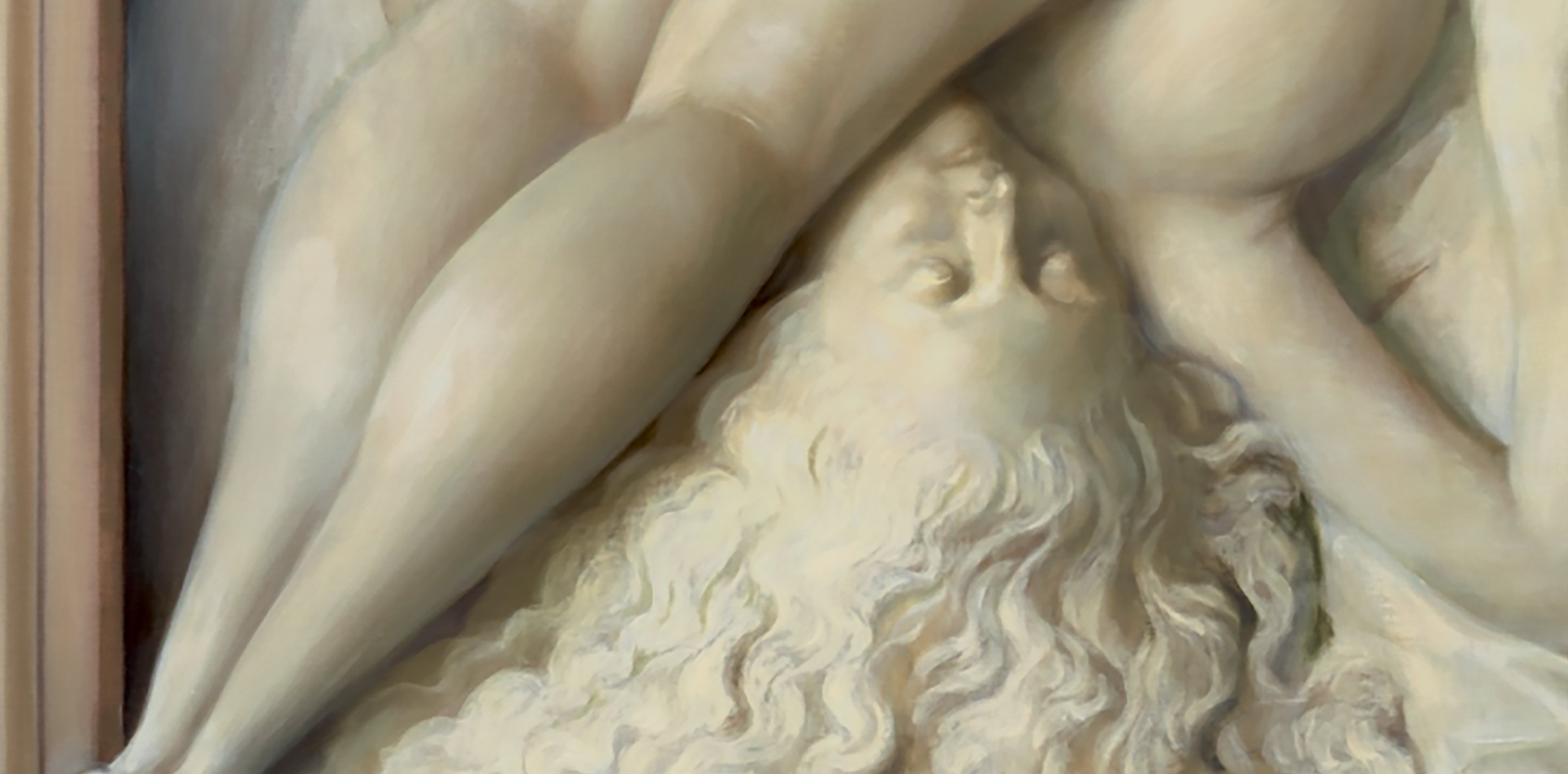

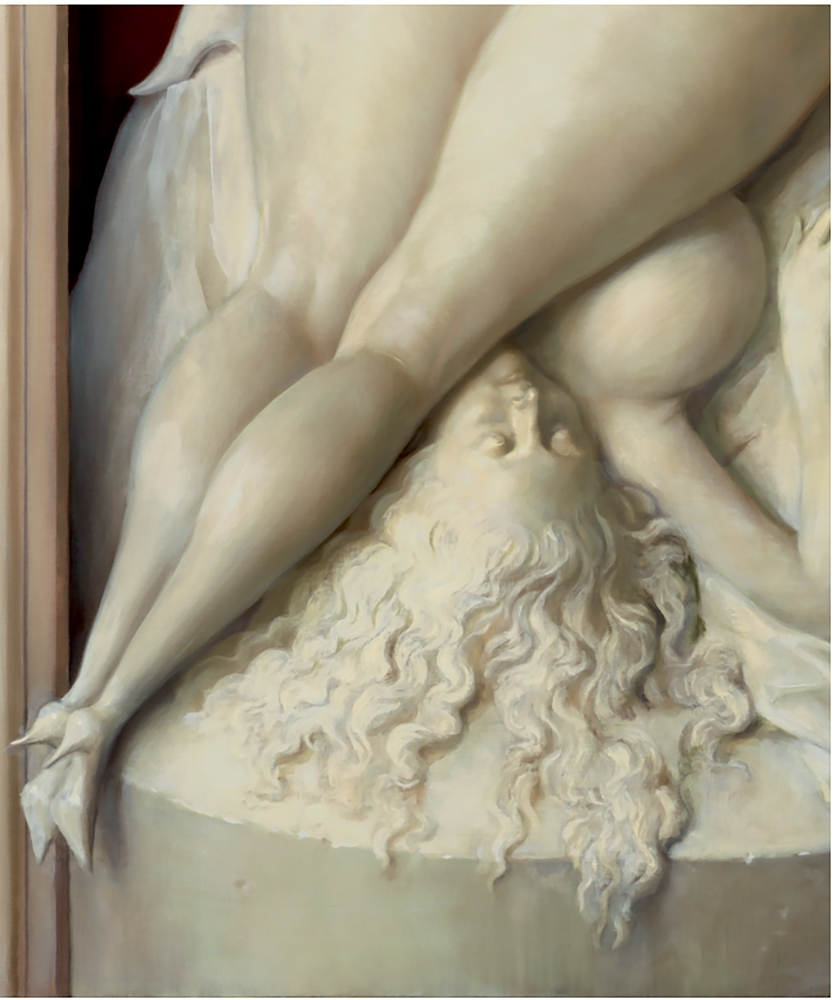

His subjects are often female, and the work shown this September at Gagosian New York remained true to form. Titled Memorial, the exhibition brings together previously unshown canvases that he has been working on since 2020. What they have in common is that colour has given way to “grisaille,” a form of monochrome painting in shades of grey, a type of representation that was traditionally found on the bases of certain buildings or in sketches.

The women he has painted seem to be located in a sort of trompe-l’œil: one seems to be coming out of the wall, another is disappearing into it. Shown in flagrantly pornographic positions and situations, several of them have the face of Rachel Feinstein, Currin’s wife, and their bodies have undergone curious deformations, often with giant breasts and tiny hands and feet Limbo (2021), for example, shows three female figures. The one on the left is clasping her giant bust with her frail hand, the one on the right is leaning forward to take off her stockings, while the figure in the middle is lying on the ground, legs in the air, exposing her orifices without a hint of embarrassment. The source of this picture was a quick sketch of Currin’s that was inspired by a 1525 painting by Cornelis Engebrechtsz he saw in the Met Museum in New York. “I made this 30-second drawing off the cuff,” he told The Brooklyn Rail, “but it stuck with me, so I decided to turn the drawing verbatim into a big painting, 80 inches high. I worked on it forever, I couldn’t figure out what my colour attitude was going to be, and it went all kinds of different places that it probably shouldn’t have gone.” So much so that in the end he rejected the final result. “The subject matter was so rude, the asshole was too big, too public, too colourful. I finally let that painting die, sanded the whole thing down, decided to remake it as a grisaille, inspired by Bruegel’s small painting The Three Soldiers [1568] at the Frick. I wanted to make it sombre, like they’re ghosts, with no colour. I decided to make it very funerary, and about halfway into it I added a frame around it, like van Eyck’s Annunciation diptych. Also, I had been using faces from advertising for years and years, and now I real- ized that these faces could be portraits of real people, so I hired models to come in, and I could paint their faces as sensitively and accurately as I could, and then turn them into stone.”

Though Currin says he was inspired by 80s and 90s pornographic cartoon strips for his canvas Climber (2021), what took him the most time to paint – several months – was the drapery. He started by borrowing from a canvas by Hans Memling before changing his mind and turning to van Eyck for the left-hand side, while the right was based on a sheet that he wrapped round a cardboard box in his studio. Meanwhile, in Sunflower (2021), the drapery is reminiscent of that in The Nativity by the Master of Flémalle, a 15th-century Flemish primitive.

The disproportion of the bodies in Currin’s work, or their repetition in Dunham’s, distance the viewer from the indecent nature of the subject matter. Both of them, at this precise moment in their careers, have decided to represent bodies engaged in sexual activity in compositions inspired by pornography. Is this an effect of lockdown? Or simply that white male painters over 50, who have fallen into disfavour with the big museums, have nothing left to lose in today’s climate – to the delight of art lovers everywhere?

John Currin is represented by Gagosian. Carroll Dunham is represented by Gladstone, Max Hetzler and Eva Presenhuber.