7

7

Who is Kandis Williams, the artist who devised the scenography for Virgil Abloh’s runway show

In her collages and performances, the African-American multimedia artist mixes pop culture and mythology to examine structures of power in contemporary society.

Interview by Nicolas Trembley.

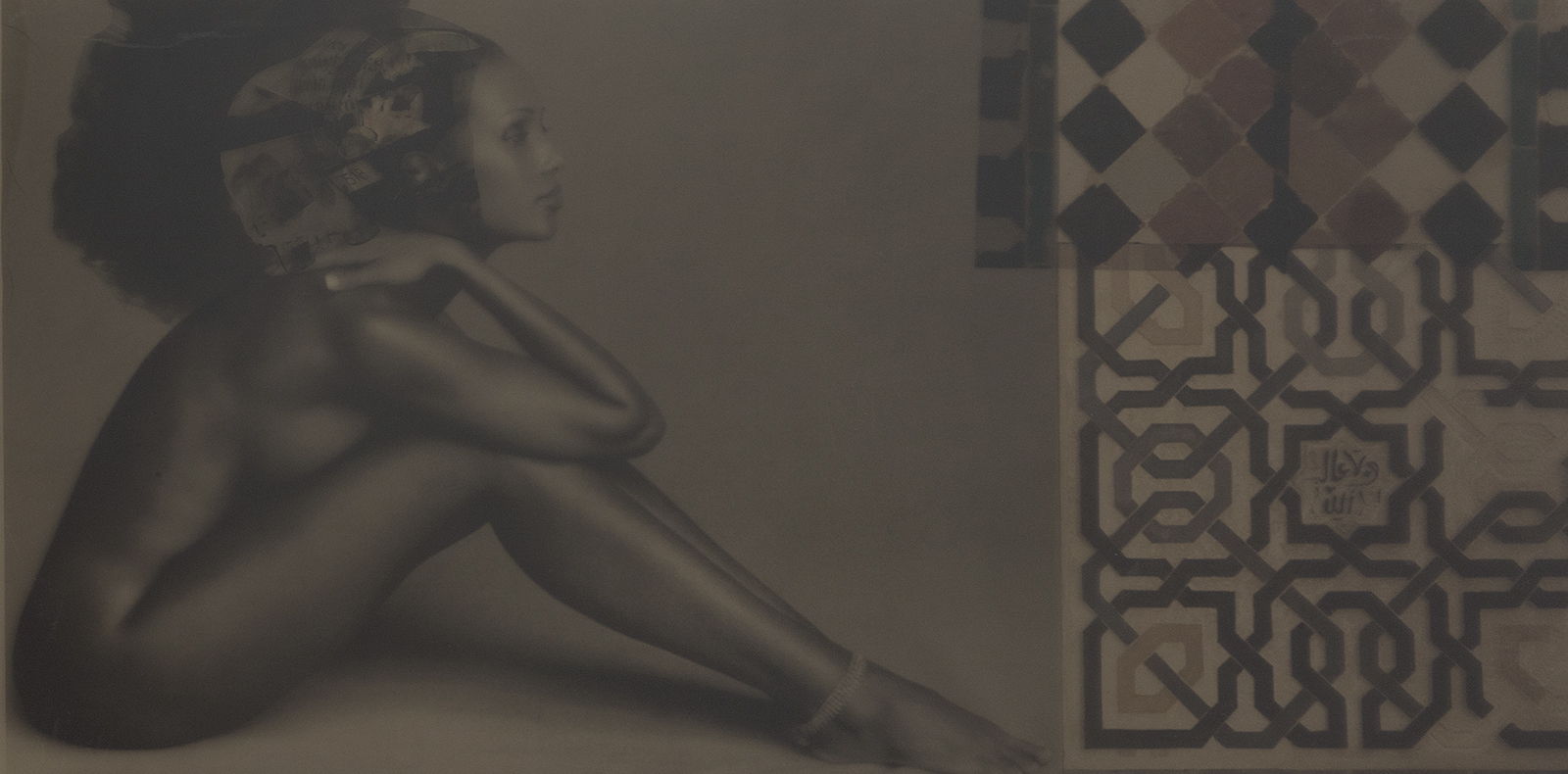

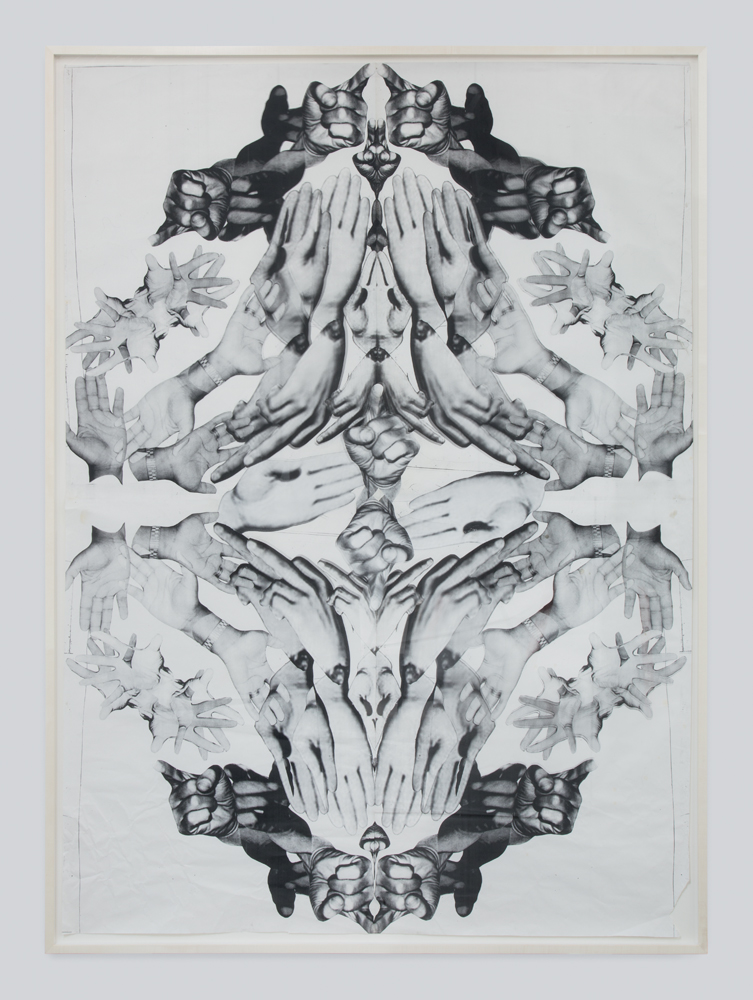

Writing, and the weight of words, are at the heart of Kandis Williams’s artistic practice, as is mythology, whose imagery she uses in her many anthropological collages. The founder of Cassandra Press, an educational and activist platform run by artists, Williams was born in Baltimore in the mid 80s, and lived for a while in Europe before settling in Los Angeles and Trinidad, now dividing her time between the two. Her transdisciplinary oeuvre – she makes both films and installations – focuses on the body as a place of experience, her performances and choreography exploring the mixing of social interactions, be they desired or imposed, conscious or unconscious (such as “being a young Black female artist today”), and setting these concepts in dialogue with imagery from dominant popular culture. Recently she devised the dramaturgy and scenography for Virgil Abloh’s autumn/winter-2021/22 Louis Vuitton Homme runway show, soon she will unveil a project at Luma Westbau with Cassandra Press, and hers will be the inaugural exhibition at the new David Zwirner gallery in New York, whose team and program will be entirely Black. We’ll be seeing her shortly in Paris too, since she’s just joined the list of artists working with the new Fitzpatrick Gallery. For Numéro, she chose to answer our questions through quotations from other artists or public figures, a way of tackling the conceptual idea of the interview to produce a collage of citations that echoes her art practice.

NUMÉRO: What’s your background? How did the context you were raised in influence you?

OAN DIDION: “It is a difficult point to admit. We are brought up in the ethic that others, any others, all others, are by definition more interesting than ourselves; taught to be diffident, just this side of self-effacing. (‘You’re the least important person in the room and don’t forget it,’ Jessica Mitford’s governess would hiss in her ear on the advent of any social occasion; I copied that into my notebook because it is only recently that I have been able to enter a room without hearing some such phrase in my inner ear.) Only the very young and the very old may recount their dreams at breakfast, dwell upon self, interrupt with memories of beach picnics and favourite Liberty lawn dresses and the rainbow trout in a creek near Colorado Springs. The rest of us are expected, rightly, to affect absorption in other people’s favourite dresses, other people’s trout.”

Do you remember your first encounter with art? What made you want to become an artist?

HENRI MATISSE: “From the moment I held the box of colours in my hands, I knew this was my life. I threw myself into it like a beast that plunges towards the thing it loves.”

DAVID HAMMONDS: “I was born into it. That’s why I didn’t even take it in school. All of these liberal arts schools kicked me out, they told me I had to go to trade school. One day I said, ‘Well, I’m getting too old to run away from this gift,’ so I decided to go on and deal with it. But I’ve always been enraged with art because it was never that important to me. We used to cuss people out: people who bought our work, dealers etc., because that part of being an artist was always a joke to us. But, like someone told me, ‘Art is an old man’s game, it’s not a young man’s profession.’ Most people can’t deal with all the loneliness of it. That’s what I loved about California though. These cats would be in their 60s, hadn’t had a show in 20 years, didn’t want a show, painted every day, outrageous stamina. They were like poets, you know, hated everything walking, mad, evil; wouldn’t talk to people because they didn’t like the way they looked. Outrageously rude to anybody, they didn’t care how much money that person had. Those are the kind of people I was influenced by as a young artist. Cats like Noah Purifoy and Roland Welton. When I came to New York, I didn’t see any of that. Everybody was just grovelling and tomming, anything, to be in the room with somebody with some money. There were no bad guys here, so I said, ‘Let me be a bad guy,’ or play with the bad areas and see what happens.”

You’ve developed an artist-run publishing platform called Casandra Press. What’s the intention behind that?

KANDIS WILLIAMS: Cassandra Press is a non-profit, artist-run publishing and educational platform producing lo-fi printed matter, class-rooms, projects, artist books and exhibitions. Our intention is to spread ideas, distribute new language, propagate dialogue centring ethics, aesthetics, femme-driven activism and Black scholarship.

What were you looking at as a child and what do you look at today?

DIANA ROSS: “Instead of looking at the past, I put myself ahead 20 years and try to look at what I need to do now in order to get there then.”

What are the main image sources in your work?

WEB DU BOIS: “But art is not simply works of art; it is the spirit that knows beauty, that has music in its being and the colour of sunsets in its headkerchiefs; that can dance on a flaming world and make the world dance too.”

You work with collage, video, writing, installation, watercolour, performance etc. Is there a medium you prefer among these?

TONI MORRISON: “I thought of myself as like the jazz musician – some- one who practises and practises and practises in order to be able to invent and to make his art look effortless and graceful. I was always conscious of the constructed aspect of the writing process, and that art appears natural and elegant only as a result of constant practice and awareness of its formal structures. You must practise thrift in order to achieve that luxurious quality of wastefulness – that sense that you have enough to waste, that you are holding back – without actually wasting anything.”

WOLFGANG TILLMANS: “The true authenticity of photographs for me is that they usually manipulate and lie about what is in front of the camera, but never lie about the intentions behind the camera.”

How important is the idea of hazard in your practice?

VIOLA DAVIS: “I worked in television; I’m the failed pilot queen, I’ve done so many television shows, pilots, theatre … When you do it for so long, I’m telling you, you get to the point where it becomes varied because you take what’s available for a number of reasons. It’s just an occupational hazard.”

FREDERICK DOUGLASS: “I prefer to be true to myself, even at the hazard of incurring the ridicule of others, rather than to be false, and to incur my own abhorrence.”

You’re not attached to a particular style – you seem very free.

KEHINDE WILEY: “My style is in the 21st century. If you look at the process, it goes from photography through Photoshop, where certain features are heightened, elements of the photo are diminished. There is no sense of truth when you’re looking at the painting or the photo or that moment when the photo was first taken.”

GEORGE S SCHUYLER: “What mattered such little things when the very foundation of civilization, white supremacy, was threatened?”

How do you install your works? Is the display important to you?

MARVA COLLINS: “Trust yourself. Think for yourself. Act for yourself. Speak for yourself. Be yourself. Imitation is suicide.”

MAYA ANGELOU: “Do the best you can until you know better. Then when you know better, do better.”

How do you choose the titles for your pieces?

LISA FRIEDUS: “I believe that titles are the accessory to a painting as a piece of jewellery is to a glorious outfit. Captions add appeal, intrigue and sometimes amusement to the painting and are a subtle wink from the artist.”

Where do you see your work in the history of art?

DIEGO RIVERA: “Every good composition is above all a work of abstraction. All good painters know this. But the painter cannot dispense with subjects altogether without his work suffering impoverishment.”

Have you ever felt yourself associated with a particular community or some kind of movement?

TSCHABALALA SELF: “Still, I’m very sceptical of the fetishization of Black artists that’s consumed the current moment. I do not feel comfortable, for example, with my works being up for auction. It’s entirely inappropriate and unnecessary to auction work, especially mine: I’m a Black American artist, and I paint Black bodies. I’m a descendant of slaves in this country, so it’s unfathomable that people could come to me, with glee, to ask if I’m excited about seeing my work, which shows Black figures and bodies, being auctioned. That shows me that people have no real understanding of Black American history, and they don’t understand anything about me and the specificity of my ethnicity as a Black person in America. It’s over their heads.”

Is there anything you would like to make people conscious of through your art in these special times?

RENEE COX: “I’m trying to create my own propaganda for the enhancement of Black folks. I’m focused on people who look like me. That’s why I’ve returned the gaze: to let my people know that they don’t need to have this subservient slave mentality. Returning the gaze is natural for me but there’s a radical nature to it, too. A lot of artists don’t want to talk about it because they’re afraid. Some are comfortable with the monies and the accolades. As far as I’m concerned, they’re not doing anything for the race. And they’ll say, ‘Well, I don’t have to. I’m just an artist. I’m not a Black artist, I’m just an artist. I’m not a Black woman artist, I’m just an artist.’ What are you talking about? When I walk into the room, they see I’m a Black woman artist. When they look at the work, they assume it wasn’t Muffy in New England who made the work. Why are we running away from who we are? For whose benefit? I’m Black and I’m proud, and as a woman I’m all-powerful. I am the giver of life. Put my ass on a pedestal.”