21

21

Interview with Wolfgang Tillmans : “You art is only as interesting as your thoughts are”

From blissful techno parties scenes ender to tender bits of bodies and intimate portraits of contemporary figures, like Frank Ocean on the cover of his Blonde album (2016), Wolfgang Tillmans has become one of the most famous names in contemporary photography. For his latest show at Chantal Crousel gallery, where he unveiled new works made during the past 8 years including the pandemic, the German 52-year-old met with Numéro.

Interview by Matthieu Jacquet.

Wolfgang Tillmans knows how to use image like no other to speak about our times. For three decades now, the German artist has never stopped exploring the corners of the sensitive world as a photographer but also as a musician, curator and activist, constantly finding new ways to marvel at its beauty. Berlin techno nights’ sweaty underground atmosphere, youth and fresh naked bodies inhabiting German forests, tender bits of skin caught in a bedroom and even faces of the people who embody the zeitgeist, be them famous or anonymous – he photographed them all. Used to capturing portraits and bodies, the artist also experimented through projects that could be qualified as more “pictorial”. After starting his Silvers series – analog prints stained thanks to chemical reactions – during the 90s, he created his Freischswimmer (litterally “free swimmers”) during the 2000s, colored cloudy and abstract landscapes that were born thanks to light techniques in the darkroom.

In his latest solo exhibition at Chantal Crousel gallery, Wolfgang Tillmans once again showcases a very neat and precise project. His work, an ongoing infinite material he is constantly exploring and rearranging, expands there with new pictures he made during the past 8 years, including the pandemic. Here, the artist produced them in many different formats : some of them become 6 by 9 feet prints he pins on the wall, while framing others or developing them on small-sized photo paper before taping them to the wall, making the visitor getting closer and further constantly. Tillmans also plays with scales inside the pictures themselves, going from a city’s nocturnal skyview to details of a blue butterfly tatooed on an anonymous skin, even including his own self-portrait through a smartphone’s screen. Human body is always here in his photographs, even when physically absent, like in folded Adidas red shorts or dry sweat traces on a black tee-shirt, but we can also guess it behind ripe avocados, which have been delicately placed on white bedsheets. Going way beyond traditional still lives, Wolfgang Tillmans’ works are, indeed, filled with life. The German artist gave Numéro a photography lesson, while assuming the upcoming transformations of images and languages.

Numéro : How have you chosen the works in this new show?

Wolfgang Tillmans : There isn’t a clear narrative, nor a clear connection of subject matters even though they are distinct, but I think what unites all the works is that hey speak to senses and states of being – liquid, solid states, the softness of tissue or skin, hardness of bones under the skin and trees… Because we have been sensorily deprived or sensorily overloaded in certain areas for more than one year now, works touch things on different level, responding to this deprivation or saturation. Of course, the center of the works is the body, which appears in the self portraits, in the FaceTime moments, in the clothes reflecting the three-dimensional silhouette that they cover… Everything feels connected by a desire to make new pictures. Even though certains things are recurring subject matters, I always feel moved to take a new version of a previous subject if I feel there is something new I can add to it, like that drapery of a tee-shirt with salt on it, which is something I haven’t seen before – the physicality being inscribed in such a direct way, the liquid suddenly printed on the fabric. And there are these four large scale non-figurative pictures, the Silvers, which are actually very figurative. We could see Japanese landscapes there, for instance.

Don’t you see them as abstract works?

The word abstract is a funny one as it is misused all the time. For instance, Vincent Van Gogh’s Sunflowers are abstraction of sunflowers : in real life, the actual flowers don’t look like how Van Gogh painted them, but he made an abstraction of them. In my Silver series, you have a solid surface of blue pigments and traces of chemicals, which is all very concrete. These pictures are no abstractions of the sky but products of their own making, they are not representing anything else than their own process, made of some photochemical reactions gone wrong. But you could also see a swimming pool in that.

Many artists make one project and then move on to the next. Your body of work is like an infinite artistic material that you can revisit and remodel every time you display it in exhibitions or in books. Aren’t you sometimes scared by its never-ending potential?

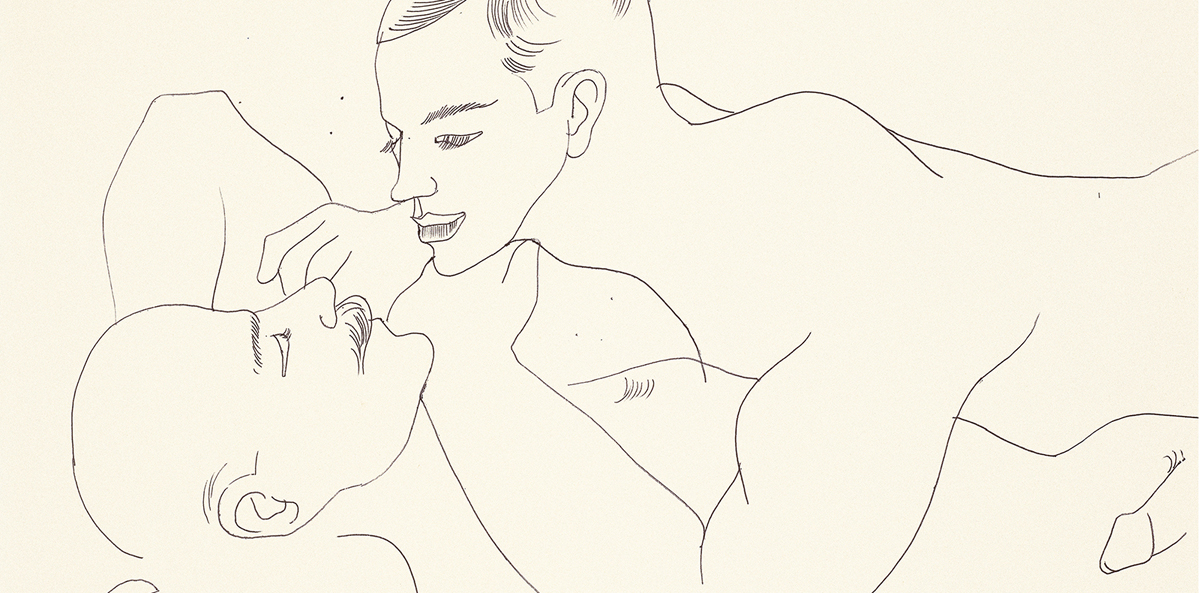

Potentially, yes, because you can never be sure of that not happening, but not for now. Artists are often afraid to not look like their time, or that their work would becomie outdated. That is a risk that you don’t have to take, because there is no guarantee you can look into the future and predict what is going to be timeless and what is not. I never felt that fear. In this exhibition, for instance, 95% are new works from recent years, and there are four pictures from 1991 or 1992 : the picture of the back with a hand on top of it is actually thirty years old!

I thought it was one of the newer ones!

Exactly, and it’s not a photograph I could have done 15 years ago. Looking at time, there are pictures I made 30 years ago that seamlessly could be from today. Next to it, the other picture of a naked back is vey recent, and they are standing next to each other while being 25 years apart. That is the experiment in this exhibition : all the works seem new, but they are not. At the moment, I am also working on my retrospective exhibition at the MoMA [to take place in 2022], so since lockdown I have been revisiting which works I want to show, went through my archive and rediscovered other works. Maybe the pool of my practice is very wide and infinite, but each composition is very specific. At the Chantal Crousel gallery, when you look at my works it in a very zoomed out way, you can say “this is three times Tillmans”, but when you zoom in you notice their big differences. That’s the challenge which I don’t tire of, but it’s hard to make it new every time.

“My primary goal is that my pictures should depict what it feels like to look through my eyes.”

We have a spontaneous tendency to think of photography as a very flat and bidimensional medium, but I think your visual work has always been very physical. The living experience of space is so central to your photographic work, as well as your performances or your music. How have you adapted to the digital shift of this past year, if so?

I have not ventured much into digital exhibitions last year, even though there were considerable invitations to do so. Many people have made fun of online viewing rooms, but I’m not that cynical : they really are pdfs that you look at. If you look at my website, I have been updating my online viewing room for years, showing how I installed my work in every exhibition of the last decade. To this day, these platforms stay the nearest experience to discover something when you can’t move there. The pandemic has highlighted that, but to show what I’ve been doing on four continents in the last decade is something that can only be communicated by photographing space. That, in itself, is a language.

You recently gave an interview on France Culture, where you mentioned how fascinated you still were with the magic of photography, especially analog, and its ability to make the picture appear on paper. How has your relationship with photography changed over the past thirty years, and with the emergence of new means and media?

There is an ongoing negotiation inside of me between the shutter speed of the photograph, the resolution of the film and the light conditions. They are three contradictory graphs that work all against each other: the longer the shutter speed is, the more you are likely to shake the camera and create a blur in the picture; in order to reduce it you can open the lens, the aperture, but you decrease the depth of film; or you can increase the speed of the film by increasing the ISO, which makes the picture grainy. Instead of setting on only one mode and working with a tripod, I am constantly finding myself exploring the limits in a way or another. For example, the concrete columns I show in the exhibition are very extreme digital photographs in the way they are taken with an 8000/second exposure time and a 3200 ISO, which we couldn’t use without making the picture unreadable. Technology has always sparked an interest in me. For instance I was one of the first photographers to use inkjet printing at the beginning of the nineties, because I loved the texture of the ink on the paper with no glass. I always felt the fine grain film was just enough to represent what it felt like to look at the world through an eye. When the new digital cameras came out in the late 2000s, I really had to learn a new language, which was sharper that what the eye could see. That was a very seismic shift.

“There really isn’t a bad camera, there are only cameras”

I saw you outside earlier, taking pictures of your assistant with your phone. If we look at your Instagram, you don’t seem to create hierarchies between techniques and tools to make photography. Do you also print, show and sell your smartphone pictures?

You know, there really isn’t a bad camera, there are only cameras. It’s only bad when it goes against your expectation, what you hope the camera can do. When the camera is as flat as a matchbox, like a smartphone’s, you cannot expect to have a great depth of field play. Primarily, my goal is that my pictures should depict what it feels like to look through my eyes : at first, I did that with a 100 ISO fine grain film, and then after 2010 I gradually realized that this hyper-focus of the new cameras has grown with general HD-ness of life. Now you can zoom into everything.

Indeed, children that were born after 2010 have that instinctive reflex of zooming into pictures with their hands!

And they have no awareness of what that means, technologically! In the last years, some of my photographs I was actually only able to make because of the smartphone camera. In the show, there are three of them. I don’t make a big gesture about it, but it does somehow represent my reality, and I feel it’s artificial to say that these can’t be artworks. Though I always assume that people understand that I don’t see the pictures I post on my Instagram as artworks. They are more like “photographs as a language”.

Your Instagram is indeed very reflective of you as an artist, even though we don’t see a lot of the actual works you show in exhibitions. We are getting a glance at your universe, and there are also articles and long texts that really express your opinions and political views. But would you ever print and frame that?

In some instances, yes, but it’s very rare. I wrote a photo essay in Aperture magazine, with the title “Are photographs words?”. I had this feeling that we are really at a pivotal moment in history, where we are transitioning potentially to a time where there is a pictorial language just the way that we have words. Over the past 2-3 years, we have started to use pictures, at first as a joke, but now we are expressing very complex emotions through pictures, pictograms or emojis. Again, it’s always a little bit touchy to speak about these things in interviews because it sounds like old men with beards asking: “do you remember when the phones weren’t there?” (Laughs). But I have a feeling things are up to a change.

I find it very difficult to describe your pictures in the sense that they seem to specifically speak about one cannot say with words. Still, you use words quite frequently and also write your own lyrics for your songs. Do you find it easier to express yourself with words?

Certainly not, otherwise I wouldn’t have started making pictures. If one only describes my pictures by what is on them, one does not really describe why they are special. Are they really special because there is a person sitting by a table in a room? Of course not because of that, but because of the “how”. This “how” is evading words, and is the frustration many artists have. In painting, over hundreds of years, the language has evolved to describe the texture, what is happening in these centimeters of paint, the canvas, the modulation. In photography, it’s a particular problem as people are still stuck with about four adjectives, like “blurred” or “focused”, which are not describing why one can recognize some photographers from a mile away. Interestingly though, language has somehow interested me all along.

“The good thing about photography is that an interesting thought can be potentially realized in a second.”

But you are also very invested in writing your own music!

Yes. During the last six years or so, I may have gathered a feeling of urgency to use more of a performative language, which was kind of where I started in my late teens. I wrote like a hundred lyrics, and somehow, it also moved behind the camera. I also see the exhibitioners as performers: their work is indeed the result of moving around the space.

How do you manage to stay inspired with everything that you do?

With the music and the political campaigns, during the last 5 years I found that these new areas were not detracting from photography. They were actually keeping me inspired and taking time away from my practice, rather that sitting and thinking about what I should do next with the camera. All of this allows me to think about other things, just like teaching which I did in Frankfurt from 2003 to 2009, curating exhibitions in my space Between Bridges [exhibition space Tillmans opened in 2006 in Berlin], where I see these 3 days a month thinking about other people’s works as something that keeps things moving. The good thing about photography is that an interesting thought can be potentially realized in a second. You art is really only as interesting as your thoughts are, and not necessarily your ideas. As long as I stay genuinely interested in the world, in life, in people and people’s art, I feel like I am okay.