1

1

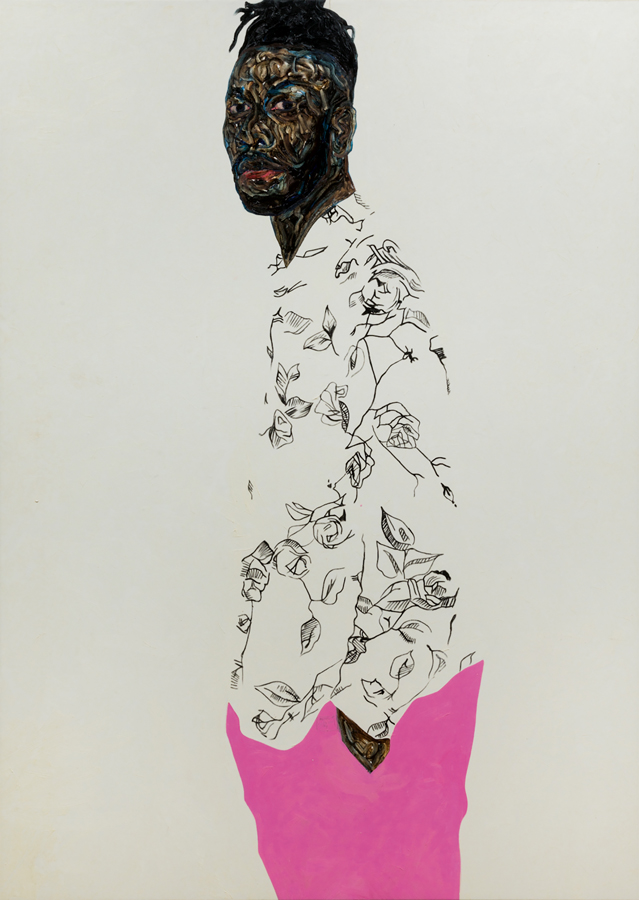

Interview with Amoako Boafo, rising star in the art world

The Ghanaian artist, who is now based in Vienna, paints remarkable portraits of figures from the African diaspora. Among his fans is Kim Jones, who was inspired by Boafo’s work in his most recent Dior Homme spring-summer collection.

Interview by Nicolas Trembley.

Having arrived on the scene barely three years ago, Amoako Boafo is one of the revelations of young African painting. Born in Ghana in 1984, he now works in Vienna, and his style is clearly influenced by the Austrian master Egon Schiele. Boafo’s output consists mostly in large-scale full-length portraits, whose faces are painted in shades of brown and burnt sienna using the fingers, a technique that allows him to “encode the different nuances of skin colour” he sees in his friends, his family and figures he finds inspiring or interesting, whose images he mostly collects on social media. What do they all have in common? They belong to the African diaspora. Contrasting with his vivid subjects, his patterned backgrounds and clothing are often monochrome and realized in pastel shades. British designer Kim Jones was recently inspired by Boafo’s work for his 2021 spring-summer Dior Homme collection. Boafo was scheduled to show at Chicago’s Mariane Ibrahim Gallery, but the exhibition has had to be cancelled because of the pandemic. Thanks to his recent success on the market, however, he is now planning to build an artists’ residence in Ghana, which will open as soon as sanitary conditions allow.

Numéro: Tell us about your career path.

Amoako Boafo: I grew up in Ghana’s capital, Accra. My first experiences with art involved drawing: when I was a teenager, my friends and I would organize drawing competitions – it was like a game. But the idea of becoming a professional artist wasn’t considered possible in Ghana. My career really began when I decided to study art in Ghana and then to do a master’s in Austria.

How has your approach to art evolved since then?

I’ve always chosen subjects that are linked to my world: my friends, my family and the powerful Black creators who are emerging just about everywhere right now – designers, exhibition curators, artists, musicians, etc. – who inspire me and to whom I wish to pay homage. I don’t necessarily say who they are: some subjects remain anonymous, others may have their identity subtly revealed through the title of the work, and then there are those who are explicitly named. A lot of my titles refer to the paint colour I’ve used. My subjects are partly real and partly imaginary, and I find a lot of my visuals on social networks.

What importance does the studio have for you?

Capital importance: I paint absolutely every day. My work is about multiplicity – I never stop adding things and trying out new experiments in each canvas I paint (and sometimes I paint five at a time). I’m continuing to explore the portrait, its poses and postures. A portrait can be expressed in many different ways – the genre offers an infinite number of motifs to try out.

Do you work in series, or is each canvas independent?

Up till now my work has been fairly serial, but at the moment I’m concentrating more on the works themselves, as well as on developing my technique, rather than exploring one and the same narrative for all the paintings in a series. I find it gives me more freedom. I’m also working on a new group of works that involve landscape and large formats.

How would you describe your pictorial technique, particularly with respect to colour?

Nuances of dark brown, ochre, purple, cobalt blue, moss green and saffron yellow are mixed in an organic movement made with the fingers. Years of experimenting produced this technique, which makes my subjects more beautiful. The absence of a tool – and therefore of an obstacle – frees me and allows me to achieve a very expressive skin colour that I could never get with a brush. A simple movement can create an incredibly intense energy and reveal highly sculptural figures, which I adore, with a certain lack of control. It’s fairly paradoxical really: you’re taught to use a brush, and instead you end up going back to the origins, finger painting, the primitive gesture as used by the first humans. I need to be reassured in this way. But I only use my fingers for the skin. For the European-style “wrapping paper” I explore all the possibilities offered by photo transfer, a more recent technique. These patterns decorate the textiles worn by my characters and, in certain cases, also constitute the background and sometimes the foreground.

Do you pay particular attention to the design of your exhibitions?

It’s rarely me who does the hang – I leave that to my gallerists and to the curators. That said, when I’m creating my pieces, I’m very attentive to scale, with respect to my view of the subject, as well as to the beholder’s. This is fundamental for me, because my work is above all about elevation and representation.

Do you feel close to a particular movement or community?

The communities I identify with are the African diaspora in all its forms.

What are your wider ambitions for your work – do you imagine it becoming part of the “big his- tory” of painting, or fitting into a more specific pictorial vein?

Where the history of painting is con- cerned, the juxtaposition of ancient techniques and contemporary portraiture has played an absolutely essential role in my career develop- ment. In Vienna I’ve sought to undertake a sort of dialogue with contemporary Black artists, prolonging my own experiences from back when I lived in Ghana. It’s kind of about encoding all the nuances of skin colour.

How has the pandemic affected your practice?

All it has done is to show me the extent to which we’ve lost physical contact. Sometimes, when I’m making my portraits, with the tips of my fingers I accentuate the whirls and eddies traced in paint, to give birth to a direct contact with the body, a bit like a caress. In this respect, lockdown has only reinforced all the intentions contained in my work.

Amoako Boafo is represented by the Mariane Ibrahim Gallery in Chicago, marianeibrahim.com