8

8

Encounter with the artist Matthew Lutz-Kinoy

Matthew Lutz-Kinoy explores every medium, from painting to costume to performance. At New York’s MoMA/PS1 this spring, he’s collaborating with artist Tobias Madison in a new staging of a play by cult Japanese dramatist Shuji Terayama.

Interview by Nicolas Trembley.

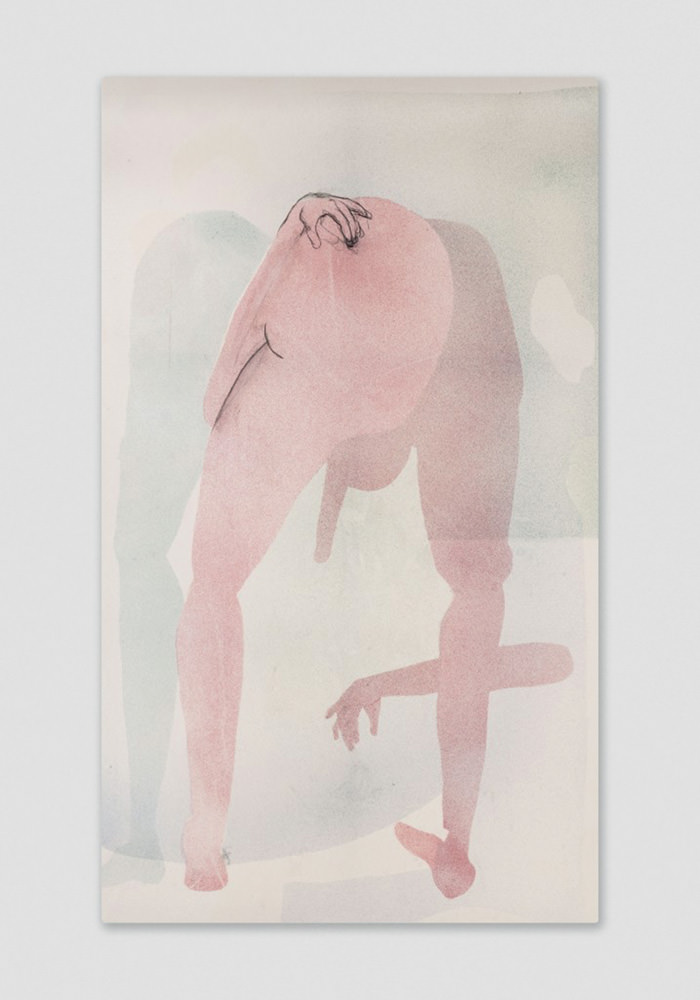

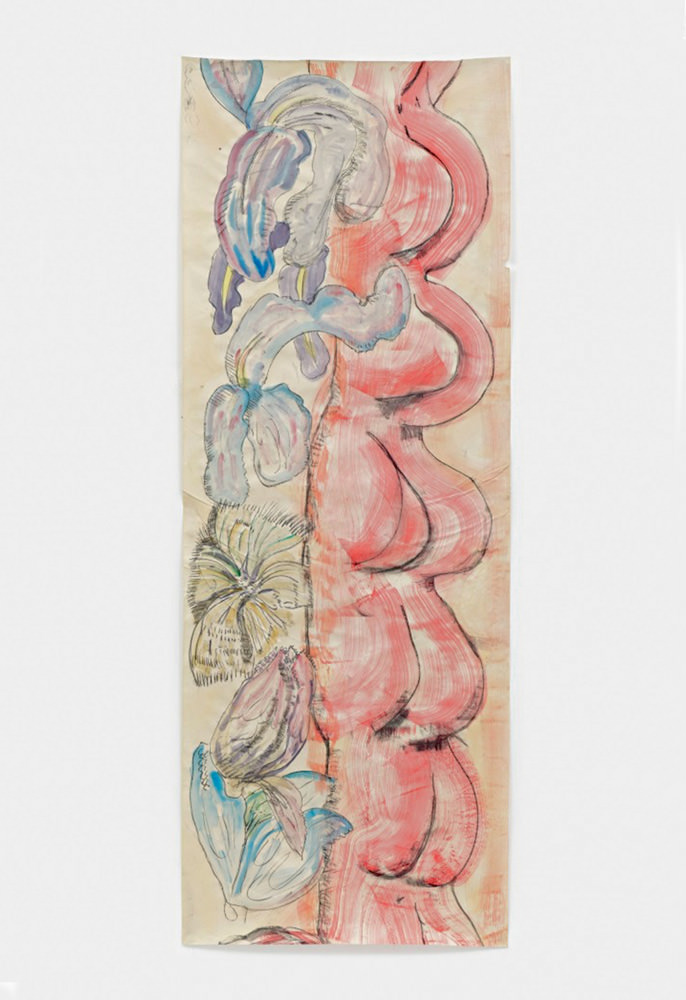

Watching Matthew Lutz-Kinoy at work on one of his large paintings, which (sometimes) include mythological characters, you get the impression of a gushing well of creativity. He works quickly, and knows exactly what he’s doing and where he’s going. But Lutz-Kinoy, with his panoramic curiosity, refuses to confine himself to just one medium and is constantly exploring new horizons. Costumes, disguises and fashion (he collaborates with the stylists at Eckhaus Latta) form part of the various performances he puts on, which are often realized in partnership with other artists. In March, at New York’s New Museum, it was with the music producer Sophie (aka Samuel Long, with whom he founded a group) that Lutz-Kinoy staged a reading about the influence of contemporary pop music, while in April at MoMA/PS1 he’s teaming up with artist Tobias Madison to stage a play by cult queer Japanese dramatist Shuji Terayama. And this summer, in Naples, he’ll be displaying his ceramic masks at the incredible Palazzo Donn’Anna, a place of mysterious legends that looks out across to Mount Vesuvius. But it was in Los Angeles, at his new studio, that Numéro met up with the eclectic young artist.

Numéro: You’re a native New Yorker I believe.

Matthew Lutz-Kinoy: Yes. And it takes most people who grow up in New York a lifetime to realize that it is not the only centre of the universe, although most signs still point to that as the truth.

Did you study art? And if so, where?

I studied in the East Village at the Cooper Union School of Art, and after that continued my research at the Rijksakademie in Amsterdam.

Which artists first marked you? And what are your references and inspirations?

I thought a lot about Keith Haring growing up in Brooklyn. I remember zooming past his Crack is Wack mural in the family car on the FDR, later paintings in the LGBT centre in the West Village and then more recently painted terracotta ceramics in blue-chip galleries. When I first encountered John Giorno texts around his sexcapades in New York it was through the José Esteban Muñoz book and I went weak in the knees. The biographic memory shared through text and a shared narrative around place is a topic that continues to interest me. I recalled the West 4th Street station and how it was a kind of coming-of-age portal for me. Reading Giorno’s texts about sex with Keith Haring in the subway bathroom in that exact station helped me in locating my corporeal self in a timeline. A trajectory that identifies a stream of visual, social, political and creative culture that developed out of 1980s in New York.

Why do you work in so many different media?

I think it’s important to challenge yourself and the world around you. By claiming a narrative around my work that locates it within a specific context, material mixed with place, I think the artworks may be imbued with a sense of presence and location. It’s important that the works are made using materials found in the place where they are produced; the lexicon of materials from brushes to paints have no master – they also represent a texture and help to tell your story. Falling in love doesn’t happen every day, and when you discover a texture, a colour, a duration or an image that attracts you, it’s important to investigate it. Developing an intimacy with a material can bring about amazing results. When I work with clay, the material is always evolving, and pieces become more complex and detailed as you develop a closer relationship to the physicality of your work.

Is there a material language in your work?

Imagine breathing in and out in the thick smog of Beijing and how different it would be to breathe the air in upstate New York. How do materials collect patina and meaning generated through experience? I don’t think creative language and identity are bound to a material language, but more so the methods of how one manipulates those materials, and their dedication to communicating through form.

What about the craft aspect of your work – do you produce all your pieces yourself, or do you also work with craftsmen?

I think education is important in terms of developing an audience and that various crafts and techniques allow for a more nuanced sense of touch in the work. I produce my works almost exclusively alone, and when I do collaborate with people it’s in the attempt to further my own education, and push my own relationship to my working methods, in order to come to new conclusions in production.

Your paintings deal with notions of figuration. Would you say there’s a certain narration in them?

When we move through the world we are constantly adjusting our bodies in relationship to space. I began to understand this dynamic through dance, where the body is constantly vibrating against architecture and other bodies redefining itself. In my paintings I use this as a starting point to open a discussion on audience and scale.

Is this why their format is often so huge?

I would like them to be larger. Then I’ll ask myself the same question.

You just had a solo show in LA at Freedman Fitzpatrick, which consisted in a large installation that took over the entire gallery. Can you tell us about its relationship to ecology?

The show is titled To Satisfy the Rose. In an average garden the rose is the most frivolous and thirstiest flower, soaking up water to plump its luscious petals. Since my move to Los Angeles I have stopped considering the rose in my own gardens due to the drought and advancing desert landscape. I have decided to install a painted ocean wave in the gallery as a symbol of our saline-filtered futures.

What’s your approach to exhibiting your work?

I think of the exhibition room as a stage, and the elements inside of the room guide the viewer in a dramaturgy. I imagine organizing my most recent show as though someone were reciting a book of poems in a public park, with each one being read in a different scenic location along a lakeside, from early afternoon to sunset.

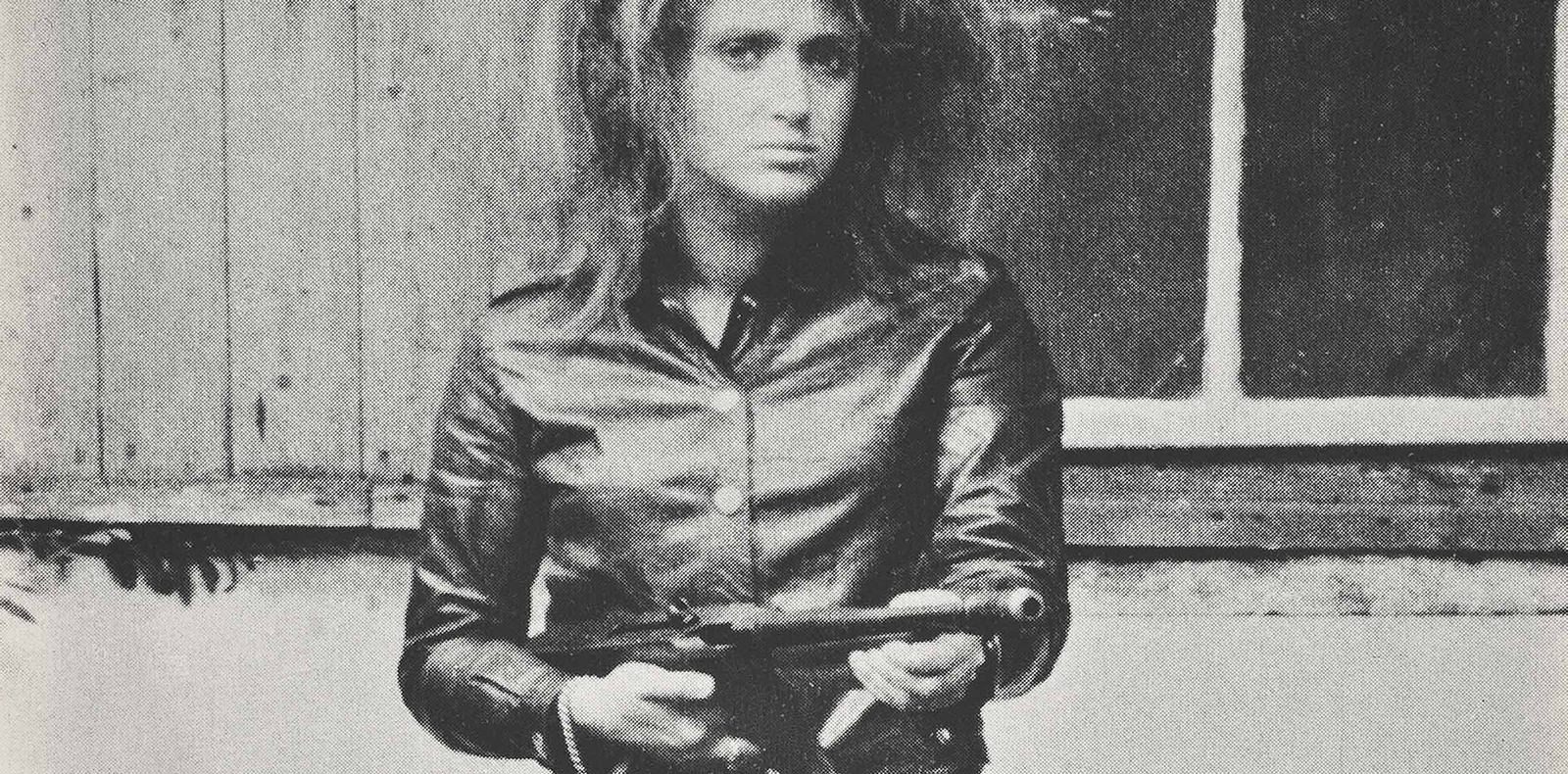

In April you’ll be putting on a performance at MoMA/PS1 in New York. Can you tell us something about this?

At the end of April I’ll be staging a performance entitled Rotten Wood, the Dripping Word. It’s something I’ve developed with the artist Tobias Madison and it’s inspired by one of the first plays by the poet Shuji Terayama. He left a huge impression in 1970s Japan, and we both take a lot of inspiration from his body of work and are excited to share our interest in Terayama with our community. We’re working with an amazing cast, with performers from Berlin and New York.

Do you feel that you’re part of a certain generation of artists? Or part of a particular group?

No, not at all. I am constantly feeling out of step with current trends or motifs. I find comfort in more traditional forms – when you have history you don’t have to feel lonely.

Who would you say is your audience?

I find that I’m usually only having intensive dialogues with three artists: James English Leary, Natsuko Uchino and Chelsea Culp. I’m interested in a very expanded audience, because you’re able to achieve the most interesting results when speaking with strangers.

Rotten Wood, the Dripping Word, by Matthew Lutz-kinoy and Tobias Madison, 23 and 24 April 2016, MoMA/PS1, New York. Matthew Lutz-Kinoy is represented by the Freedman Fitzpatrick Gallery.