6

6

David Adjaye: the architect who was knighted by the Queen

The exhibition “David Adjaye: Making Memory,” at London’s Design Museum, showcases seven major projects by the Anglo-Ghanaian architect that explore the fascinating theme of collective memory.

“Architecture is a good way of transmitting history, even if it’s the history of a traumatism,” confides David Adjaye as we sit down to talk in an office at London’s Design Museum. Born in Tanzania to Ghanaian parents, he says he’s conscious of the difficulty of such a mission, but this is precisely the idea he’s come to defend at the inauguration of his latest solo show in the British capital. David Adjaye: Making Memory opens with a strange visual abecedary: from the pyramids at Giza to the statue of suffragist Millicent Fawcett by Gillian Wearing, the gaze runs through a sort of historic classification of the memorial aimed at the neophyte, the monuments being categorized under often rather reductive labels such as “ancient,” “tomb,” “obelisk,” “space” or “statue,” as though they were incapable of bearing more than one meaning. But this rather dubious pigeonholing nonetheless poses a pertinent question, that of the role of architecture as a representative tool in our collective memory.

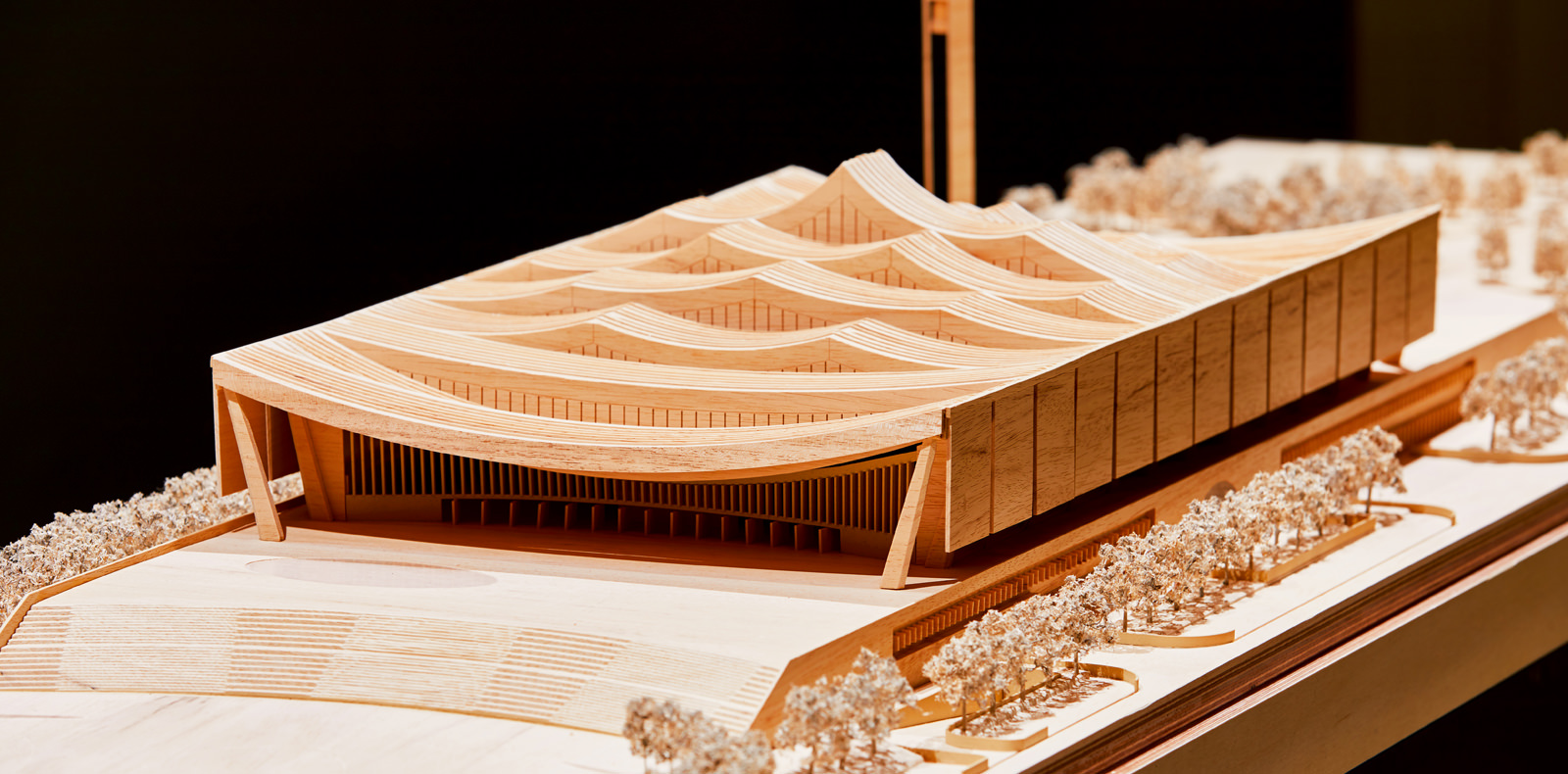

For Adjaye, it’s a question of moving away from the concept of the static monument towards a shared, communal experience. It’s a vision which evidently finds its echo in the Zeitgeist, since his office has just been chosen to construct Britain’s new Holocaust Memorial, the model of which is on display at the Design Museum. Planned for a site next to the Houses of Parliament, in Victoria Tower Gardens, the memorial will include a basement “learning centre” designed in partnership with Ron Arad Architects. To get there, you’ll have to walk past one of the 23 bronze “wings” which are separated by 22 spaces representing the countries that were touched by the Shoah. “The Holocaust has a complex history in England,” says Adjaye, “and our intention is to reveal the profound nature of these terrible events so that they don’t become buried under their past” – words which are not merely symbolic in a country where anti-Semitic and negationist speech is on the rise and the government is planning to close the borders after Brexit.

Among the other projects shown in the exhibition is the National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, D.C., which was inaugurated by Barack Obama in 2016 and won the Beazley Designs of the Year prize in 2017. Here once again Adjaye imagined architecture as a symbol addressed to the collective memory, the building’s form echoing the Yoruba statues of West Africa, while the filigree design of its cladding recalls the classic motifs of African-American metalwork. What’s more, the museum was built on the former slave route in the heart of the U.S. capital – a revenge for some and a scandal for others.

“Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it,” said the American philosopher George Santayana. Beyond the role, that a building dedicated to the memory of an event must play, the memorial project asks another question that is just as delicate: are the duties of memory and education more important than those of reparation? On the subject of restitution, Adjaye is very clear: for him, cultural objects must be returned if the spoliated country requests it and as long as the political situation is stable enough to ensure the preservation of the works in question.

“Heritage must return to its country of origin, but that mustn’t add one trauma to another, that of restitution to that of spoliation,” he’s quick to add. “In the cases of appropriation of one people’s heritage by another, links inevitably become established between the two. Returning works allows a new dialogue to be established. These exchanges will form part of their common history.” He takes the opportunity to applaud the position taken by Emmanuel Macron “who took the courageous decision for France to return works that had been spoliated from Africa” – a gesture he knows will be difficult to put into practice, but about which he remains optimistic.

But Adjaye is also a man who’s resolutely turned towards the future, and was recently nominated to take part in the Rolex Mentor and Protégé Arts Initiative. Launched in 2002, the programme is designed to promote the handing on of the world’s artistic heritage from one generation to the next. As such it’s another way of constructing our collective memory.

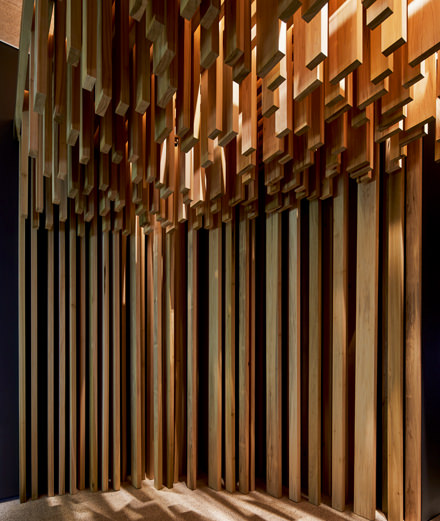

David Adjaye: Making Memory, Design Model for the forthcoming Ghana National Cathedral by David Adjaye. Photo Ed Reeve Museum, London, till 4 August.