3

3

Buck Ellison: the contemporary art of photography

American artist Buck Ellison dissects the wealthy, right-on california society that he’s frequented since high school. For Numero, an old school friend explains his method.

par Peter Denny.

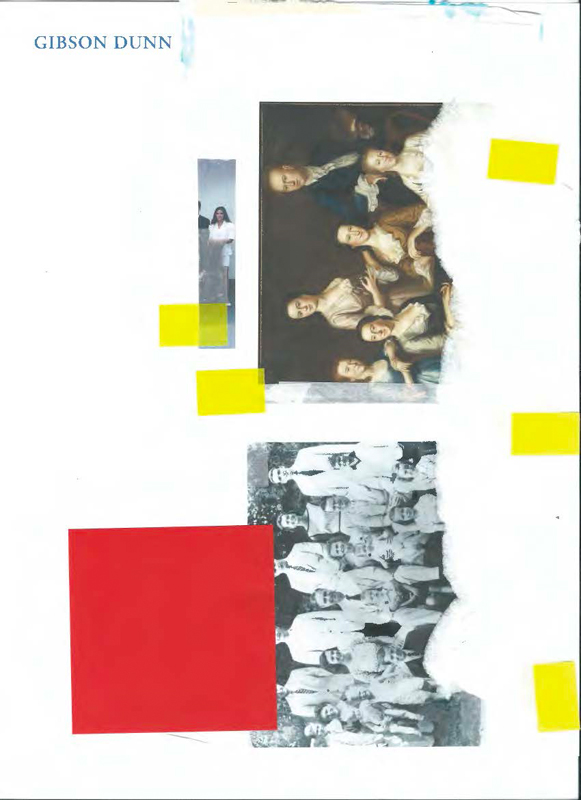

Buck makes collages to sketch out ideas for his largeformat photographs. In his home studio, part of the apartment he and I have shared for four years, reference images are taped up on the walls: his own photos, printouts from Google searches, magazine pictures, scribbled notes. It’s an ever-rotating cast of characters: prepschool girls playing lacrosse, historical portraits, hot blond men, Gwyneth Paltrow, gardens and school buildings. Even out of his studio, the objects in our house make their way into his work, from our plates to our shopping bags. Buck’s photographs may be single images, but I always see an element of collage in how they represent a long, considered process of layering many different references. Everything in the frame is consciously placed and informed by research. The collages sometimes end up being artworks themselves, as in the case of the two featured in this article, in which different forms and eras of portraiture are placed on prestigious Gibson Dunn lawfirm letterhead. Though not directly connected, this echoes Christmas Card #2 (2017), a photo of a family sitting in front of an old portrait. The collaging of portraits connects today’s more casual depictions of wealth with imagery traditionally associated with power and social standing.

I could tell Buck was putting these associations together as early as high school, where we were surrounded by living collages of inconspicuous consumption. At what was known as the “hippie” prep school in Marin County, California, we studied a politically liberal curriculum heavily focused on social justice and inequality issues. But the student body was almost completely insulated from everything we learned. When looking at Buck’s work, it’s hard for me not to recall the girl who opted for a used Subaru when she was offered any car in the world; the gaggle of white boys in Bob Marley T-shirts arguing about whose gas-station sunglasses were cheaper; the summer programs where families paid $20,000 to send their teen on community service in Bali; the oil-money heiresses protesting the Iraq war. The more money people had, the more they were expected to hide it. I think that because it was so important for overt wealth not to be seen, Buck became curious about the ways in which it was still visible. Over time this interest transcended our crude high-school observations into a more poignant study of this niche of wealth that aspires to be progressive while remaining very much connected to and benefiting from the systems of oppression it protests. Despite their best efforts, the subtle details of these people’s lives reveal the connections: portraits of European war heros or aristocrats, plates and silverware handed down for generations, antebellum family law firms.

As much as Buck and I were able to laugh about our absurd upbringing, we were not exempt from its psychological effects. And it’s Buck’s deep familiarity with the subject matter that allows his work to do more than just criticize. He doesn’t pass judgment, but rather gives visibility to the social norms of a conflicted class who often are not even aware they are engaged in an aesthetic language so few can understand. Collage, both as a means to an end and a final product, shifts the focus away from one person or story, and emphasizes the overall context. Looking at Buck’s photos, I always find myself drawn in by feelings of calm, beauty, and comfort, but also a sense of unease. It’s up to the viewer to feel what they feel, but what’s important is that they look in the first place. In an era of unprecedented wealth inequality, no one should be exempt from deeper inspection.

Exhibition, from 7 november to 8 december, Balice Hertling gallery, in Paris.