8

8

An encounter with Robert Longo, monumental artist exhibited in Paris

On the occasion of his “Luminous Discontent” exhibition at Thaddaeus Ropac, Numéro looks back at its encounter with the artists in his New York studio.

Interview by Thibaut Wychowanok.

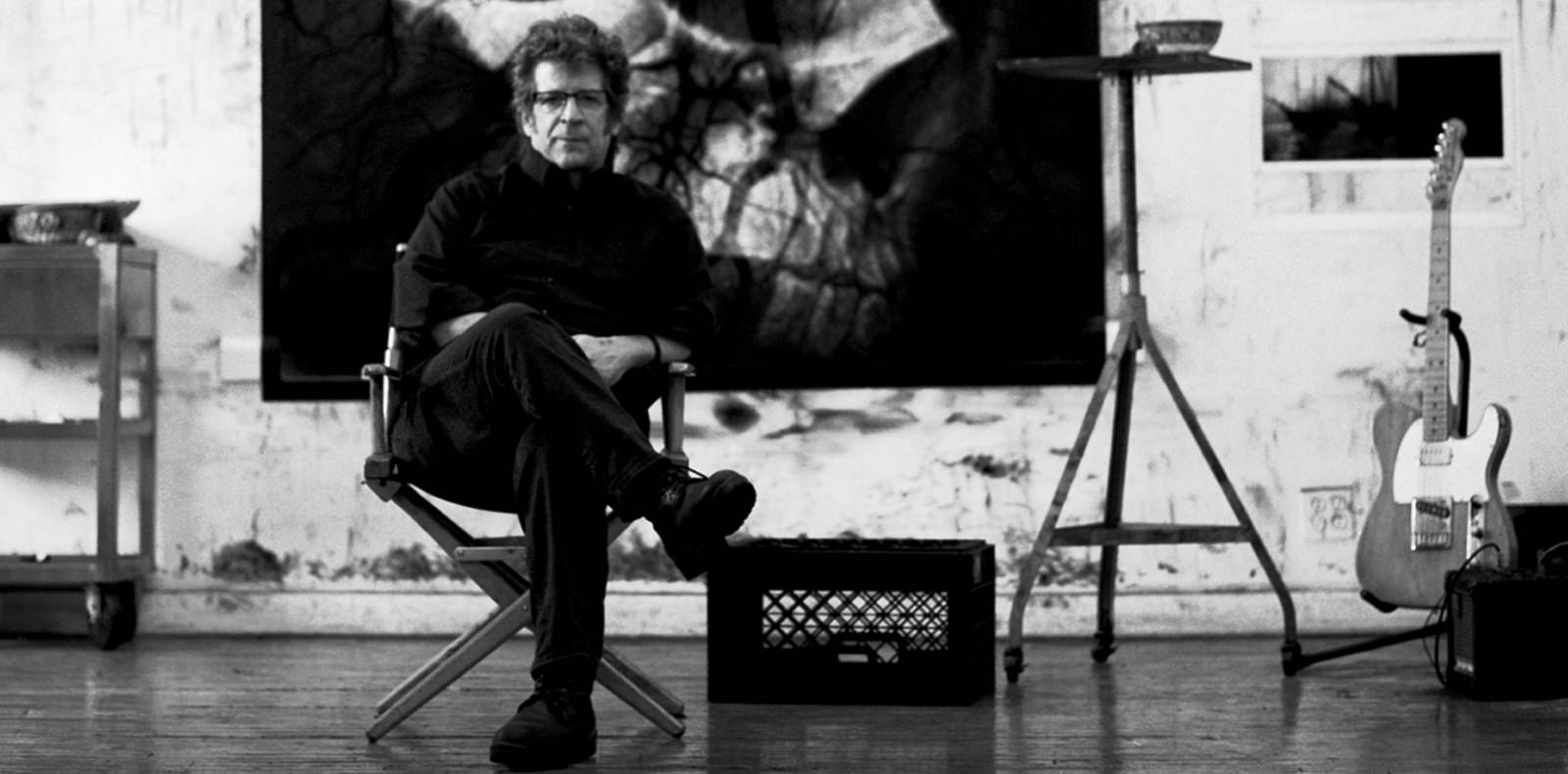

A legendary artist from the late 1970s, Robert Longo owes his fame to his fabulous and monumental drawings. We visited his New York workshop where the American still works on his graphic œuvre with just the same fervour.

Numéro: A monumental drawing of chandelier floating over an agitated sea welcomes us on arrival in your studio. Do your recent works lean more toward surrealism?

Robert Longo: The year 2015 marked an indisputable change of direction for me. I decided, after two important exhibitions last year to start thinking about new avenues. One of them got me interested in poetry. It’s not a new interest but my dyslexia always kept me back, made it hard for me to read. So I decided to concentrate on an author who was already familiar and that was Edgar Allan Poe and in particular The City in the Sea. The unreal drawing you refer to was inspired by that research. But there’s nothing surreal about these new works. They’re more from the collusion of elements, like an accident between two cars that creates a new object.

In this fantastical vein, your studio also contains a drawing of tree branches mixed up with a skull. Lurking death and imminent danger are themes that have long traversed your oeuvre.

That one has a particular resonance because it was made three years ago, almost to the day, after I had my stroke. Under duress I found myself facing a multitude of images of my own brain, which I found most inspiring. This drawing is a bit like an anniversary present [laughs]. But generally I’m wary of overly personal works. Art should strike a subtle balance between a personal interest in a subject or object and the relevance of that interest for society at large.

This drawing could also very easily join the tradition of horror or fantasy book covers by the likes of Stephen King. On the wall of the studio there’s a drawing that really means a great deal to me. It’s an American flag floating over a black background. I dedicated this work to Howard Zinn, a great historian who specialised in American history and left us in 2010.

The United States has always been a fertile land of images and themes for your works. How do you view your country today?

America is drifting right now. But for me the paradox is that it also represents the last possible hope for the world. I live in Brooklyn and there I see Pakistanis, Indians, Japanese, Orthodox Jews and Italians all living happily side by side. This country was built on a particular state of mind that I regard as team spirit. Americans have a sporting mentality. The good side to that is that we work well together. The flip side of the medal is that we strive for one thing only. Like all sportsmen we strive to win. And that often stops us from thinking straight. After 9/11 no one bothered asking why those people should hate us so much. We just had one thing in mind: to win. So yeah being American is a powerful aspect to my work. I’d go even further and say that my works come from a particular viewpoint, that of a white American man.

The drawings, the big scale, the black and white are three other characteristics of your work. What does this reveal about your work?

One of the reasons I chose to draw, being completely honest, is that when I first got to New York I didn’t have enough money to do photos or videos. I soon realised that drawing was sadly viewed as the bastard child of major art forms like painting and sculpture. So I wanted to do drawings on steroids, amplify them to they weighed in as heavy a sculpture. One of my friends refers to my drawings as having “intimate immensity”. I take a planet and I do a three meter drawing. I take a rose and again I do a three meter drawing… I also find the idea of creating work from dust alone very beautiful. I mean the charcoal I use isn’t far from that. In my mind I’m always aware of the incredible fragility of my drawings, starting with the material, which is paper. When a photo gets damaged you can print another one. But you can’t reproduce a drawing that easily. As for the black and white, your question reminds me of something my youngest son said. He always thought my pictures came out of a newspaper. And I think that I’ve always associated black and white with the truth. When I was very young, the photos that represented reality, that showed the war in Vietnam or earthquakes, they were always black and white.

On that note where do the images you use for your drawings come from?

I’ve realised that the images I have in mind, and that I find online or elsewhere, always come from a visual memory that formed between the ages of 6 and 13, that vital moment of existence where you move from childhood into adulthood. When I try and understand why my drawings have such an epic aspect to them, I remember that as I kid I saw Ben Hur and Spartacus at the movies… As for my best known works, the Men in the Cities, I thought back to the time when my New York friends on the new wave scene all wore suits. I think in reality I was influenced by the original version of the movie Ocean’s Eleven with Frank Sinatra which I’d seen when I was very young. When a girlfriend of one of my son’s saw these drawings at the Metropolitan Museum, she asked me if I’d been influenced by the latest advertisement for iPad which oddly looked like them. At that moment I understood that when you’re lucky enough to create such a prototype, you lose its paternity. This loss of authorship interests me a great deal because I see a wonderful irony in it. They steal my images which are themselves inspired by other images – although not identically reproduced, I’d never do that – but that I did steal in a way. And so the circle is complete.

Luminous Discontent, from April 16th to May 22nd 2016, @ Galerie Thaddaeus Ropac, 7, rue Debelleyme, Paris IIIe.