9

9

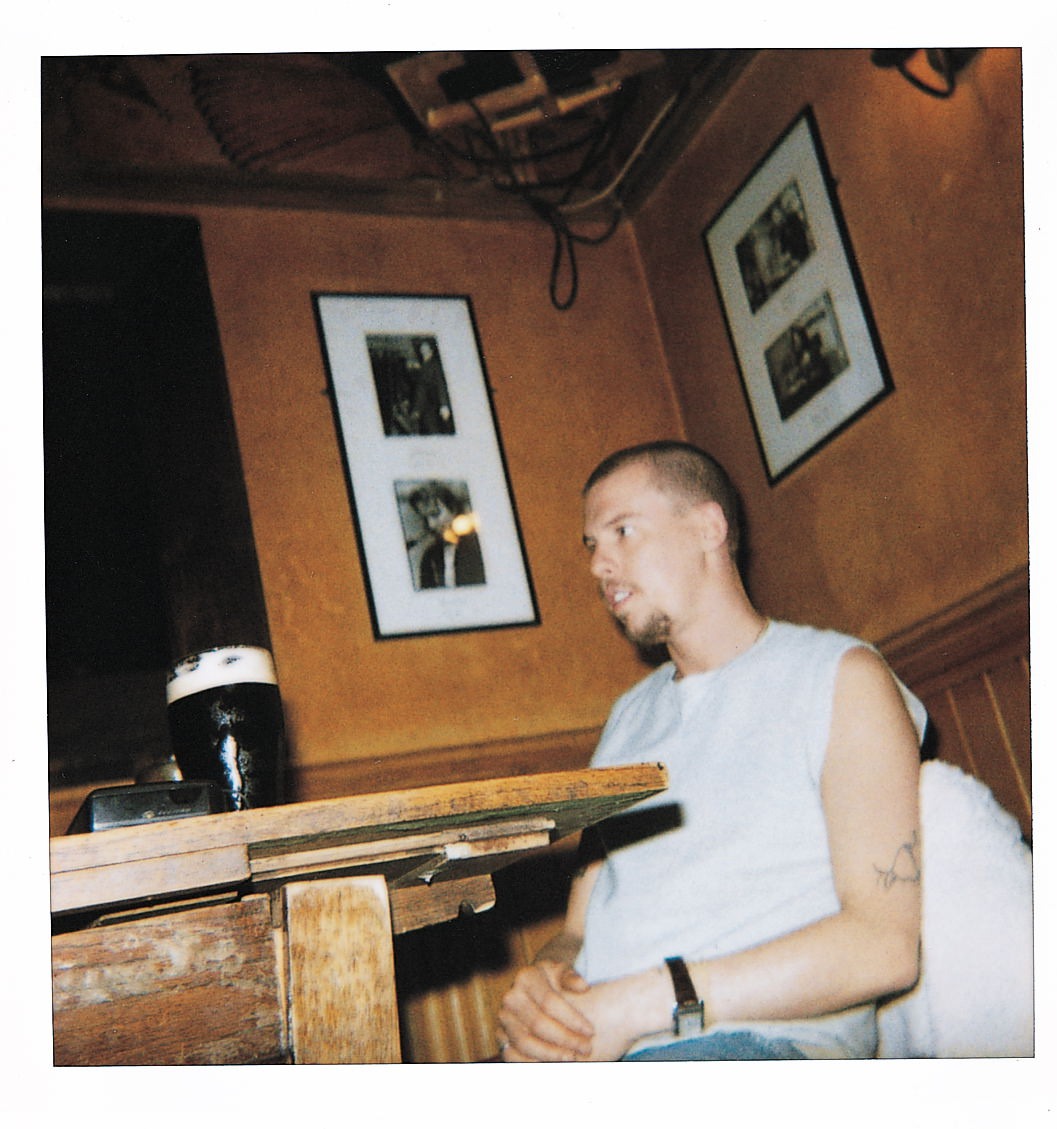

Alexander McQueen: Portrait of a bold designer with a legendary destiny

Andrew Wilson’s new biography of Alexander McQueen, “Blood Beneath The Skin,” traces the unusual path of the designer. On the occasion of the book’s release, Numéro takes a look back at the universe of this visionary, who has tragically left us.

par Delphine Roche.

Published on 9 September 2020. Updated on 17 October 2025.

His shaved head, legendary frankness and Cockney accent earned him the nicknames “bad boy” and “hooligan.” Conformists claimed to be offended by his provocative spirit— while secretly taking pleasure in the shiver of the forbidden that he breathed into an increasingly policed industry. Like others before him, Alexander McQueen rejected the criticisms that are the lot of free spirits and avant-gardistes. And each season we rushed to see his audacious and spectacular runway show, which constituted a significant event, a moment of poetry that went beyond a simple collection presentation. His clothes, quasi-haute couture, romantic and dark, would have been enough to make his reputation. But for Alexander McQueen, the clothes were part of a larger message conveyed by the show as a whole.

Was McQueen an artist? He certainly knew how to put on a performance. The designer pushed every limit of the traditional runway show, shocking the public by incorporating disturbing elements into his presentations. Horror infiltrated the beautiful in order to guide it toward the sublime. “I use things that people hide: war, religion, sex, and I force people to look at them,” he once said. In 1995, he used sex as a political metaphor. In his Highland Rape collection, the torn clothes and haggard appearance of the models alluded, he later explained, to “the rape of Scotland by England.” In 1999, Aimee Mullins, an athlete and double amputee, walked the runway on prosthetic legs made of sculpted wood. In McQueen’s world, handicaps rub up against ideal beauty, enlarging its definition. Beyond a desire to shock, Alexander McQueen sought to recenter the body in fashion. Illustrating the inherently morbid nature of the quest for perfect beauty, the dialectic of fantasy inscribed itself violently in flesh. Ultimately, fantasy erased and replaced flesh entirely, as it did in March 2006, when Kate Moss was rendered as a hologram, and in Deliverance, 20 minutes of wild defiance inspired by the film “They Shoot Horses, Don’t They.” Sadism and cruelty were on the menu: wolves among the sheep. And the wolves were in the Conciergerie, too, where in March 2002, McQueen’s winter presentation was accompanied by the howls of caged dogs.

McQueen experimented with dance, painting and theater, and all were present in his Dante-esque productions. The creative crossfire produced sparks. In 1999, Shalom Harlow held herself immobile on a rotating platform while two giant arms sprayed her white dress with yellow and black paint. McQueen demanded of his models the real work of an actor: Shalom Harlow mimed terror and hid her face in her hands, before running backstage shaking. McQueen’s endless questioning is existential; its energy visceral and tragic. Art, it must be said, isn’t often compatible with life—indeed, it has the upsetting tendency to destroy it. In McQueen’s work, again and again, models disappear, their bodies remodeled by corsets, extreme shoes and virtuoso structured lines. Diaphanous, nearly bloodless, they are overwhelmed by climbing roses, as in his October 2006 runway show. Are they living paintings or recumbent statues set upright? The poetry of Alexander McQueen had little use for such questions.

Alexander McQueen – Blood Beneath the Skin d’Andrew Wilson, published by Hardcover editions.