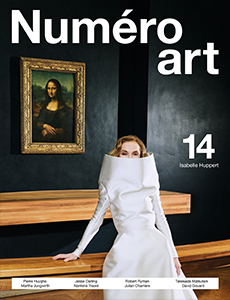

14

14

The Pinault collection at Paris’s Bourse de Commerce

Miriam Cahn, Urs Fischer, David Hammons, Louise Lawler – these are just some of the names currently exhibited at Paris’s Bourse de Commerce, home to the Pinault Collection, which is finally being shown to a French audience after a marathon 20-year wait. Bringing together some of the world’s greatest artists, the inaugural hang offers visitors a heartrending meditation on the human condition.

Par Thibaut Wychowanok.

This was an opening that was eagerly awaited, after so many years of anticipation: first announced at the turn of the millennium, plans for a Pinault Collection museum in France fell through in 2005, after which the billionaire opened spaces in Venice, and finally made it known, in 2016 that his collections would come home to roost at Paris’s Bourse de Commerce. If the expectation was palpable, it’s because, above and beyond François Pinault’s weight in the art world and his bond with stars of the market like Jeff Koons and Damien Hirst, the collection’s shows have always proved inspiring in their poetic power, their conceptual radicalism and, above all, their ability to explore the human condition in all its complexity. Placing man at the heart of everything, celebrating the madness of life, confronting death, time and impermanence, embracing all identities and celebrating otherness have been the constant leitmotivs. Other major themes include fragility, the tragedy of life, vital breath and an attention to bodies suffering or threatened in their identities – political bodies, in other words, which are revealed through art as weapons in a struggle for individual visibility and existence in the eyes of the world.

“Among the great virtues of a relationship with art is the perspectives it opens up,” writes Pinault in the catalogue’s foreword. “… Each discovery has revealed to me different universes and aesthetics, has made me understand what was foreign to me until then, and has pushed back the limits I thought I must impose on myself.” Ouverture (Opening or Overture) has been chosen as the umbrella heading for this first Parisian hang, a word that also refers to the music played at the beginning of an opera, which announces the principal themes to come. If the chorus formed by the ten inaugural exhibitions is anything to go by, the Bourse de Commerce has chosen its viewpoint – art that is open to the world and to society and that directly grapples with existential, political and racial realities –, leaving aside, for the time being, the minimalist current that is also one of the collection’s strengths.

At the luminous heart of the Bourse, where architect Tadao Ando has built his new rotunda, we find Urs Fischer’s grandiose sculptures arranged so as to form a sub- lime monument to the passage of time – obviously – but above all to metamorphosis and the inversion of values. His sculptures disintegrate with the passing days, melting away like giant candles, passing from a vertical sacredness to a humble horizontality. Art and the world are in every way overturned – and will knock the viewer over too. Still on the ground floor, France has finally honoured the intransigent David Hammons with the celebration he so richly deserves, in the form of a display of 30 or so works, all of them radical aesthetic explosions. The empowerment of the African- American community stands side by side with the artist’s uncompromising view of the violence and subjugation suffered by its members.

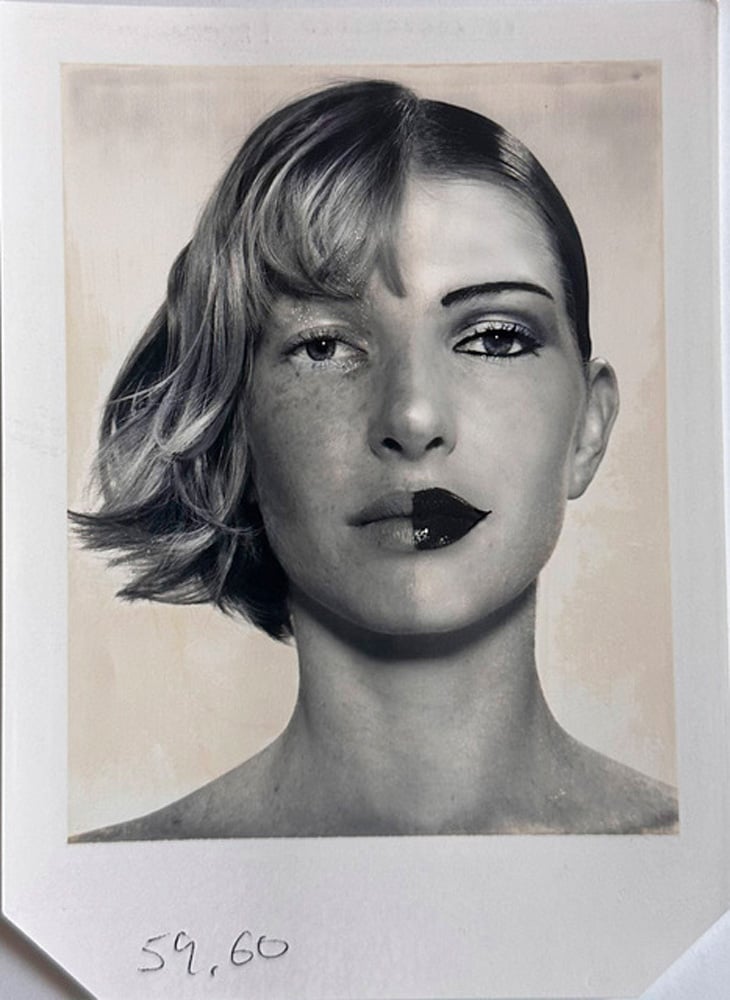

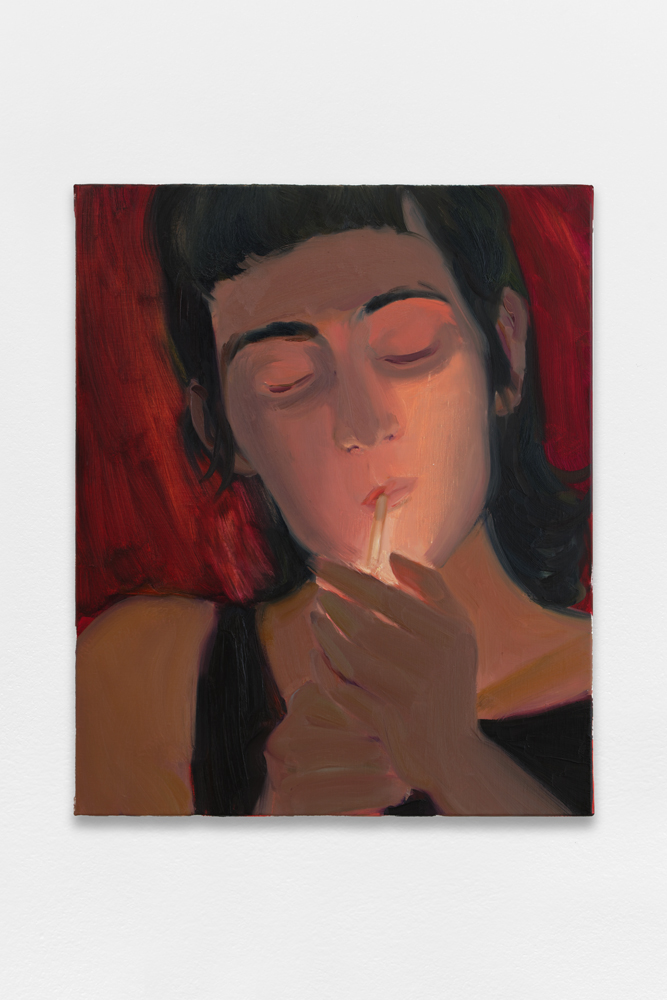

On the first floor, the photography galleries continue this affirmation of the individual through six striking displays of work by some of the greatest photographers of the period 1970–2000: the staging of the self with Cindy Sherman and Martha Wilson, the fluidity of gender with Michel Journiac, who spent 24 hours in women’s clothes, and the scathing, chilling activism of Louise Lawler. The self and the body are presented as perpetual inventions, brilliant reconfigurations at the heart of a political struggle. The human figure and its multiple identities are again discussed on the second floor, with a journey through figurative painting that explores the affirmation of identity and singularity, each time articulated through a dialogue be- tween artists born in the 50s and 60s and those born in the 80s and 90s – Peter Doig, Xinyi Cheng, Marlene Dumas, Kerry James Marshall, Luc Tuymans, Miriam Cahn, et al. The multiple faces are plural, so different and so human, conversing between generations and geographies. These exhibitions form a coherent, powerful and ambitious whole, yet are only part of a much wider programme.

As you discover the hang, certain encounters shatter mental and emotional categories. In 1989, for example, the American artist Louise Lawler created a minimalist photo installation showing a multitude of white plastic cups. Beneath its apparent banality, the work is heart-breaking. It is in fact a portrait of the American Senate, which had just voted, by 94 to six, in favour of Republican Jesse Helms’s amendment refusing to allocate funds to HIV prevention on the pretext that it would encourage drug use and homosexuality. Each senator, whether Democrat or Republican, is represented by the white disposable cup (s)he drank from; all interchangeable, like the senators who voted for the shameful bill, the vessels also recall disposal hospital cups, which patients dying of AIDS were also drinking from. Lawler’s installation forms a wall of commemoration to the dead of yesterday, today and tomorrow by pointing to and shaming the senators, printing their name and state of origin below each image. Six empty spaces stand in for those who had the courage to abstain or to vote against the bill, among them a certain Al Gore.

This conceptual and formal radicality with respect to political issues operates with the same violence in the work of David Hammons, whose artistic and political relevance and influence on younger generations remain undiminished. By transforming a basketball hoop into a flashy chandelier, he takes an object from the street – an echo of its violence – and revisits it with baroque and mannerist materials, playing with the codes of white, bourgeois art history. In this way, he questions the double bind that operates on African Americans: the only way to escape the first restriction, the ghetto, he seems to tell us, is to obey the second: assimilation into the petty-bourgeois bling dream. Hammons himself has always refused to accept the rules of an art system constructed by whites, which makes his exhibitions all the rarer, and this one, consequently, all the more exceptional. As a counterpoint to the existential tragedy of the Black community, Hammons also invites us to celebrate its empowerment. For him, in this perspective, jazz plays a key role as a form of avant-garde expres- sion invented by African Americans. “That’s what jazz taught us. My people took these European instruments and breathed into them all the misery and madness of our experience.”

Finally, one can’t talk about this opening show without dissecting in detail the exceptional display of paintings on the second floor. The young Chinese painter Xinyi Cheng, who now lives in Paris, admits that she only portrays her friends and relatives, underlining with kindness their attitudes and physical characteristics, all the while masterfully committing to canvas the mystery of their identity. Tenderness, intimacy and solidarity are what characterize some of the most powerful works on display, such as the disturbing bodies painted by 71-year-old Miriam Cahn. A living legend of painting – though not nearly as well-known as she should be among the general public –, the Swiss artist has been pursuing her own singular vision since the 1970s. The colours are strident, the bodies dissolve, the figures challenge the viewer, often with violence, and the real comes through as intense and incandescent. We should also name all the artists, both young – Florian Krewer, Antônio Obá, Serpas, Lynette Yiadom- Boakye, etc. – and not so young – Marlene Dumas, Kerry James Marshall, Rudolf Stingel, et al. – whose work Pinault has chosen to show, symbolizing a collection that refuses a flashy “icon” approach and instead prefers to initiate friendships and affinities over several decades. Though the Bourse de Commerce is the initiative of one man, it is also in a way a family affair, as well as a public space open to all. A forum for deliberation – truths are discussed here rather than decided –, it reminds us that museums are the last safe spaces of our times, the places where new individualities, emotions and ideas can emerge.