13

13

Robert Frank : The birth of a legend

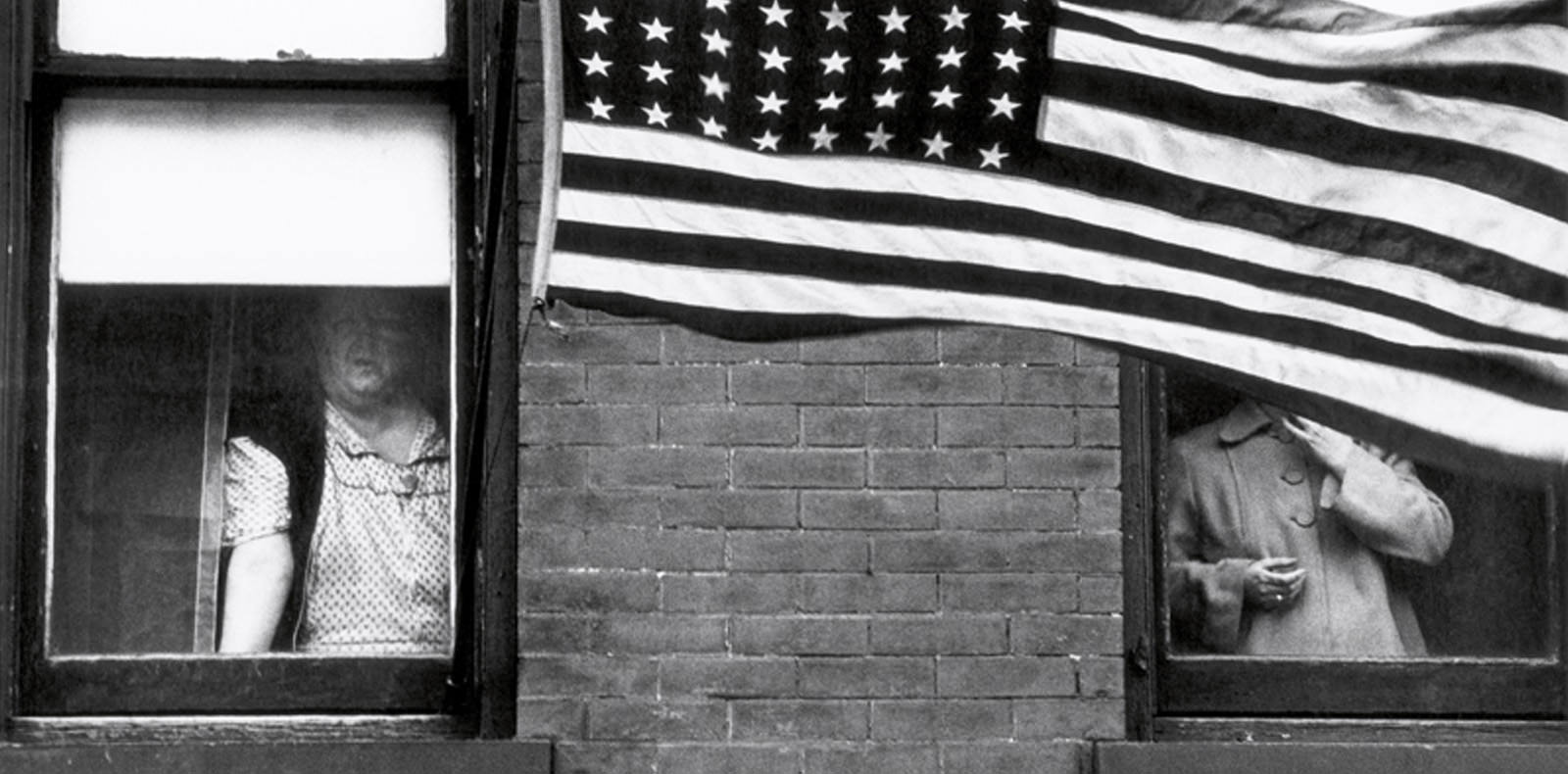

Robert Frank’s celebrated portrait of his adopted homeland, the americans, turns 60 this year. To mark the book’s anniversary, les Rencontres d’Arles are organizing a major exhibition tracing Frank’s early career. Numéro art looks back at the photographer’s beginnings up to publication of the book that made his reputation, accompanying them with rare contact sheets from the cult volume.

By Patrick Remy.

Robert Frank was born in Zürich in 1924 to a family of German-Jewish origin. His father sold gramophones and radios, as well as designing furniture, while his mother came from a family of manufactuers. Frank rarely spoke of his childhood, except in a text to accompany a collection of his father’s photographs: “He designed truly awful furniture. It was all over our house, in Zürich Enge, a very bourgeois neighbourhood. The man could get angry pretty quickly; in the evening, at six o’clock, when he came home from work, he started in on his correspondence, usually addressed to his creditors; he dictated his letters to his creditors and got angry at the smallest mistaken comma. After these letters, he didn’t want to hear anything; we turned off the news, he smoked a big cigar, he wanted to go out but my mother wouldn’t let him escape.”

His father had a rather middle-class hobby for the era – photography – which he practised on family holidays. With his stereoscopic double-lens camera, he snapped photos of his two sons and wife, but preferred landscapes. “When he made us pose, it annoyed me. I liked the photos in the stereoscopic machine. It taught me the value of a photo. It was an expensive machine, but my father never talked about how much things cost. His photos expressed his carefree side. I think he was happy to show life’s joys, and to have his family admire them. He was also an excellent storyteller,” Frank later remembered. The idea of becoming a photographer was just beginning to bud in the adolescent boy’s mind, but his father advised him to find another profession, one that could feed a family. “I was 12 during the Spanish Civil War; I saw photos of refugees arriving in France from the Pyrenees, and was really moved. That was when I discovered the power of photography. All the beauty of Switzerland, the joy, and just next door, war,” he recalled.

“After the war, Frank embarked on his first solo assignments, read the existentialists, but also Camus, and discovered some of Europe’s major cities: Strasbourg, Milan, Paris, Brussels and Amsterdam.”

Frank started out in the 1940s as an assistant to various professional photographers in Zürich, a city home to numerous magazines. He learned the ropes first with photographer and graphic designer Hermann Segesser, then alongside Michael Wogensinger and later with Victor Bouverat and the Eidenbenz brothers, working between Zürich, Geneva and Basel. But his greatest influences were Gotthard Schuh and Jakob Tuggener. One of the most prestigious of Swiss photojournalists, Schuh was interested in ambiance and subjectivity, turning away from the simple recording of raw information and the formalism of the times in favour of an independent photography in which the artistic will would take precedence over mere mechanical reproduction. Tuggener, until recently rather forgotten, “was like a beacon” to Frank, showing “the Swiss worker, the product of Swiss money, Swiss water, Swiss mountains – from within, but without sentimentality,” as Frank later put it.

After the war, Frank embarked on his first solo assignments, read the existentialists, but also Camus, and discovered some of Europe’s major cities: Strasbourg, Milan, Paris, Brussels and Amsterdam. Then, in February 1947, he set sail on the S.S. James Bennet Moore to New York. It was just a visit, he told his parents, but he would end up making his home there. Before leaving Switzerland, he put together a portfolio of 40 pictures, a disparate collection that included mountain landscapes, lakes, industrial scenes, a close-up of a flower, portraits of farmers, animals in their cages, a crowd of children, tree-trunks and a brass-band, all bound in a cover featuring a close-up of an eye.

Postwar New York was the heart of the global art world, where European refugee artists were collapsing all the codes in a climate of stiff and stimulating competition. A few days after his arrival, Frank wrote to his parents. “Never before have I experienced so much in one week as here. I feel as if I’m in a film,” he said, before adding (ironically?), “There is only one thing you should not do – criticize anything.” Frank went through his address book in search of work, contacting the Swiss-born graphic artist and photographer Herbert Matter, and the photographer Paul Himmel, who introduced him to the art director of Harper’s Bazaar, Alexey Brodovitch. Immediately recognizing his talent, Brodovitch hired Frank on a salary, and commissioned a first photo essay on fashion accessories. “I got to know Brodovitch pretty well, he knew a lot about photography. His book on ballet was an influence. And I saw the work of Bill Brandt, and André Kertész’s book, Day of Paris. Kertész’s work really moved me. And then I saw his images for the magazine House & Garden. Deep down, I’ve always kept him in my thoughts; he taught me that one could make a living with photography if one must. One is commercial work, the other is a whole other kind of work.” It was his conversations with Brodovitch that convinced Frank of the power of the book as a medium for presenting photographic work. But after a few months, Frank left Harper’s, although he continued to undertake occasional assignments for it and Junior Bazaar, even if fashion interested him very little.

“In 1948, Frank took off for South America, abandoning his Rolleiflex for a Leica.”

In 1948, Frank took off for South America, abandoning his Rolleiflex for a Leica. On his return to New York in March the following year, he sent his mother the mock-up for Peru, 4 a small book of images he’d shot there, keeping the only other copy for himself. Today, one can be found at MoMA and the other in the National Gallery in Washington D.C. Even if some of the photographs later became well known, the complete series was only published in 2008. Yet Peru is one of Frank’s most important books: its 39 photographs constitute the genesis of his art.

In the wake of Peru, in 1950, Frank got married, to the artist Mary Lockspeiser with whom he had a son, Pablo, in 1951, and a daughter, Andrea, in 1954. With a family to feed he turned to reportage, dreaming, like all his confrères, of working for Life. But success and commissions were slow to come. The art director of Collier’s, Sey Chassler, summed up the kind of situation Frank found himself in well: “You cannot be a great visionary like Leonardo da Vinci, Whistler or Cézanne and hope to fit the full splendour of your soul in the magazines of today. No one expects that of you, no one asks that of you, and no one wants it.”

Frank did, however, enjoy the support of Edward Steichen, MoMA’s first director of photography, who saw something of himself in the young Swiss émigré: a talented photographer trying to earn recognition as an artist. Another decisive encounter was Walker Evans, who encouraged Frank to apply for the 1955 Guggenheim Foundation fellowship. With the $2,500 granted him by the Guggenheim – a modest sum, even then – Frank made a few small trips around New York before buying a 1950 Ford and embarking on a nine-month east–west trip across the United States. “When I crossed the country, it was the first time I saw it, and I was in a good frame of mind, I had good influences. I knew Walker’s photographs, and I knew what I didn’t want.””

With literature as his primary passion and arguably his main influence, Frank embarked on a battle with photographic tradition. Many of the shots in what would become The Americans are under-exposed, hastily framed, with blurry and cut-off figures as well as distracting reflections. Frank proved that photography is not simply a question of technique or viewing angles, but above all of feeling. Over the course of his American odyssey, between June 1955 and June 1956, he snapped over 27,000 frames (on 687 rolls of 24 x 36 film), of which he developed about 1,000 in the fall and winter of 1956–57, only to keep a mere 83! All in black and white: “Black and white is the vision of hope and despair. That is what I want for my photographs.”

“The critic Bruce Downes qualified the book as “images of hate and desperation, desolation and our relationship to death,” adding, “Frank is a liar, perversely celebrating the misery he perpetually searches for and obstinately creates.””

It was a young French publisher, Robert Delpire, who first brought out the book under the title Les Américains in 1958. Frank’s photos were accompanied by quotations from authors as diverse as Simone de Beauvoir, John Dos Passos, Washington, Faulkner, Chateaubriand, Tocqueville and Steinbeck, selected by the writer Alain Bosquet (in France, publishing photography books without literary endorsement has always been difficult). Frank didn’t want either the cover drawing (by Saul Steinberg) or the slew of authors – he’d have prefered just a single text by Faulkner – but bowed before the experience of his friend and editor. The following year, for the first American edition, the author texts disappeared, a photo replaced the drawing, and an introduction by Jack Kerouac was added: “That crazy feeling in America when the sun is hot on the streets and the music comes out of the jukebox or from a nearby funeral, that’s what Robert Frank has captured in tremendous photographs taken as he travelled on the road around practically 48 states in an old used car…”

The Americans is a slow unfurling of images that can be divided into four chapters, each opening with a photo featuring an American flag – images of an optimistic America, or a desperate one. The book closes with Frank’s wife, Mary, and their two children (today deceased) sitting in the Ford parked by the side of the road. “Across the USA I have photographs with these ideas in mind: to portray Americans as they live at present. Their everyday and their Sunday, their realism and dream. The look of cities, towns and highways,” wrote Frank. The critic Bruce Downes qualified the book as “images of hate and desperation, desolation and our relationship to death,” adding, “Frank is a liar, perversely celebrating the misery he perpetually searches for and obstinately creates.” Puritan America could not permit a “foreigner” to criticize the American dream. A 1986 thesis written at the University of Arizona, Tuscon, looked at critiques of the book and found a number of gems: “Chicago has more facets of personality than this political harangue,” or “New York contains more candy stores than homosexuals.” Photographer and critic Tod Papageorge, on the other hand, was enthusiastic: “A continent is spanned, but its life compressed into a single grief.” But let’s leave the last (vernacular) word to Kerouac: “Anybody doesnt like these pitchers dont like potry, see? Anybody dont like potry go home see Television shots of big hatted cowboys being tolerated by kind horses. Robert Frank, Swiss, unobtrusive, nice, with that little camera that he raises and snaps with one hand, he sucked a sad poem right out of America onto film, taking rank among the tragic poets of the world. To Robert Frank I now give this message: You got eyes.”

Les Américains : un long déroulé d’images, que l’on peut découper en quatre chapitres, chacun introduit par une photographie où figure un drapeau américain. Images d’une Amérique optimiste… ou désespérée. Le livre se termine sur sa femme, Mary, avec ses deux enfants (aujourd’hui disparus) assis dans la Ford garée au bord d’une route. “À travers les États-Unis, j’ai photographié avec cette idée en tête : présenter les Américains tels qu’ils vivent actuellement. Leur quotidien et leurs dimanches, leur réalité et leurs rêves. L’apparence de leurs villes, communes et autoroutes”, écrit Robert Frank.

Le critique américain Bruce Downes qualifie ce livre “d’images de haine et de désespoir, de désolation et de relation avec la mort.” Il ajoute : “Robert Frank est un menteur, jouissant de manière perverse de la misère qu’il recherche perpétuellement et qu’il crée obstinément.” L’Amérique puritaine ne peut supporter qu’un “étranger” critique le rêve américain. Une thèse est même consacrée, en 1986, par l’université d’Arizona, à Tucson, aux critiques du livre. On peut y lire quelques perles : “Chicago a plus de facettes et de personnalité que cette harangue de politicien.” Ou : “New York a plus de magasins de bonbons que d’homosexuels.” Le photographe et critique Tod Papageorge est, lui, enthousiaste : “On parcourt tout un continent, mais où la vie est compressée dans une douleur unique.”

Pour Jack Kerouac, c’est plus simple : “Celui qu’aime pas ces images-là aime pas la poésie, vu ? Celui qu’aime Poisie, rentre chez toi mater la téloche et les gros cow-boys à chapeau tolérés par de doux chevaux. Robert Frank, suisse, discret, gentil, avec ce petit appareil qu’il lève et déclenche d’une main, a sucé l’Amérique un poème triste sitôt transposé sur pellicule, trouvant ainsi sa place parmi les tragiques du monde ; à Robert Frank, j’adresse maintenant ce message : ‘Tu as un œil.’”

Les quotations come from the books En Amérique (2014) and Looking In (2015), éd. Steidl.

Exhibition Robert Frank at Rencontres de la photographie d’Arles, from 2nd of July to 23th of September.