11

11

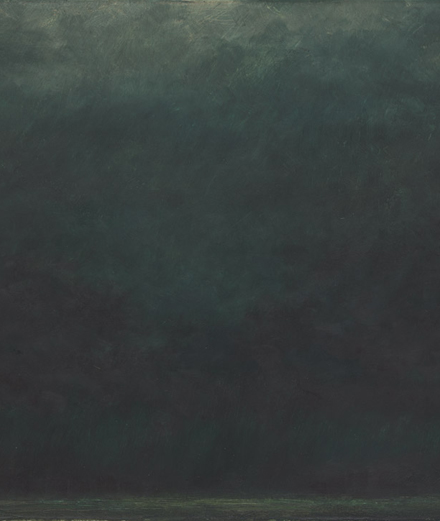

Lucas Arruda’s imaginary landscapes

Based in figuration, his luminous and almost obsessional series of landscape paintings come very close to abstraction with their painstakingly executed renderings of the effects of light.

Interview by Nicolas Trembley.

Published on 11 September 2020. Updated on 18 June 2024.

The work of Brazilian artist Lucas Arruda is very specific and serial, consisting in small-format paintings grouped under the generic title Deserto-Modelo, a term he borrowed from the Brazilian poet João Cabral de Melo Neto and which he uses for all his exhibitions. This “model” of an imaginary landscape serves as a basis for all his paintings, which run the range from rep- resentation to abstraction and fre- quently take the form of small pano- ramas in which a horizon can be glimpsed, even if it often merges with the ocean, the beach or the sky. Sometimes, though, his work be- comes more figurative, such as when he depicts the vegetal thickets of an imaginary jungle. Arruda’s paintings are difficult to date and the places they represent hard to iden- tify, but so much is our relationship to landscapes conditioned by our memories and by the history of art that they produce in us a strange impression of déjà-vu – like with the work of Armando Reverón, a Venezuelan painter whom Arrudahas studied in depth, or, nearer to home, Turner perhaps. Viewing Arruda’s exhibitions is a powerful, contemplative and, dare one say, luminous experience, since light is at the heart of his work – sometimes he even goes so far as to replace his paintings with slide projections.

Numéro: How did your background influence you?

Lucas Arruda: I was born and grew up in São Paulo, Brazil’s big- gest city, which exhibits all the chaos inherent to giant metropolises. As a counterpoint to this urban tension, I’ve always managed to escape to Barra do Una, where my father and his husband have a small house in the middle of nature. I think these getaways very strongly marked my relation to observation. In Barra do Una I developed strong ties to the tropical forest and to the beach, both of which were united in the same place at the same time.

What do you remember about your earliest encounters with art?

One of the first exhibitions I remember was Joãosinho Trinta at a SESC cultural centre in São Paulo when I was six. Trinta was an emblematic figure of carnival, parade director at the samba schools in Rio in the 80s. I was fascinated by the maze-like layout of the show, and by the multitude of colours and materials. It was a totally immersive experience, and I went back to see it again and again.

When did you realize you wanted to be an artist?

It’s difficult to say exactly when, because there was no decisive moment – everything just happened naturally. I’ve always had trouble concentrating for long, and drawing was the only activity that allowed me to really concentrate. Over time it became a practice that brought me closer to myself, a way of organizing my thoughts, and as such it became indispensable. Today, when I look at some of my earliest drawings, I see many aspects of my childhood in them. I really learned to dominate the tools of drawing so that I could express myself. It’s a very deep process which evolved towards painting, and I still feel it’s something urgent for me.

What art were you looking at when you were younger, and what are you looking at now?

Again, it’s difficult to reply precisely because I never stopped looking at paintings and I always mix up my references. My interest goes from one thing to another and often everything becomes entangled. But Armando Reverón is an artist I’ve always been drawn to.

Do you consider yourself a painter? Does the term still have meaning for you in 2020?

I consider myself an artist who works with paint, the technique with which I feel the most intimate connection. Sometimes painting ends up influencing the whole of my work, because I always ask myself questions from a pictorial point of view, for example about light, or about references from the history of painting.

When and why did you start introducing slide projections and light installations into your work?

When I took art-history classes, I was fascinated by the projection equipment. I never tired of observing how the light, projected from the rear of the machine, traversed the images on the slide. The process is fairly similar in some of my pictures, where I will look to find luminosity on the canvas by taking paint away to reach the light that comes through from underneath. After a while in the studio I began working with little slides whose very restricted acetate surface meant I lost complete control of the gesture, which led me to a new way of painting. The light installations came out of my experience with projection equipment.

How do you choose the colours for your canvases?

Right now I’m thinking a lot about colours that are not easy to define, not entirely one thing or the other, which remain in a more cerebral dimension – the colour you must think of to summon its presence. I’m also interested in washed-out colours, the palette of greys and beiges… But the most important thing is the relationship between the colours, not so much the colours in themselves.

Can you say something about your formats?

For landscape paintings, I mostly work with small formats. I feel that a landscape carries within it the desire to burst out of its limits, a sensation of space that creates a tension with the restricted size of the canvases. The tropical forest always works better on a square format, while the monochromes can adapt themselves to larger surfaces with more materiality. Over time I think my pieces have ended up finding the sizes and proportions that suit them.

How do you display your work? To what extent is the hang an important way of getting a message across?

It always depends on the space and on other outside factors, but at the end of the day it’s about creating a rhythm. It’s like building a score from a sequence, from colour, from sizes and from distances.

Have you ever felt close to an art movement or group?

I’ve never belonged to an art movement, but I’m a member of a generation of artists who are working in a socio-political context that is particular to Brazil, and I believe my work is in part a result of that.

What’s your next project?

I’d like to take part in a professional boxing fight.