10

10

Interview with the modern jazzwoman Melody Gardot

Interview by Romain Burrel,

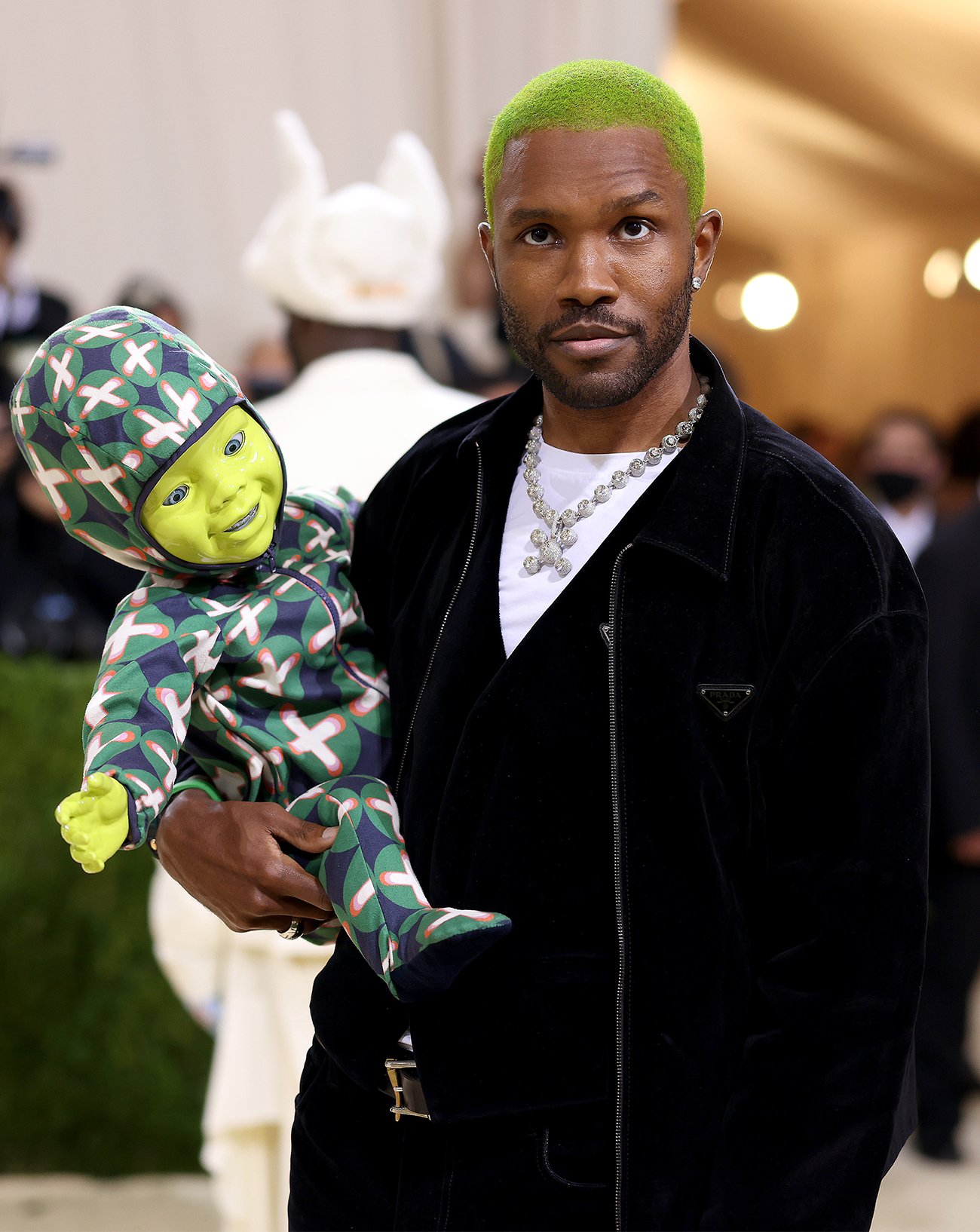

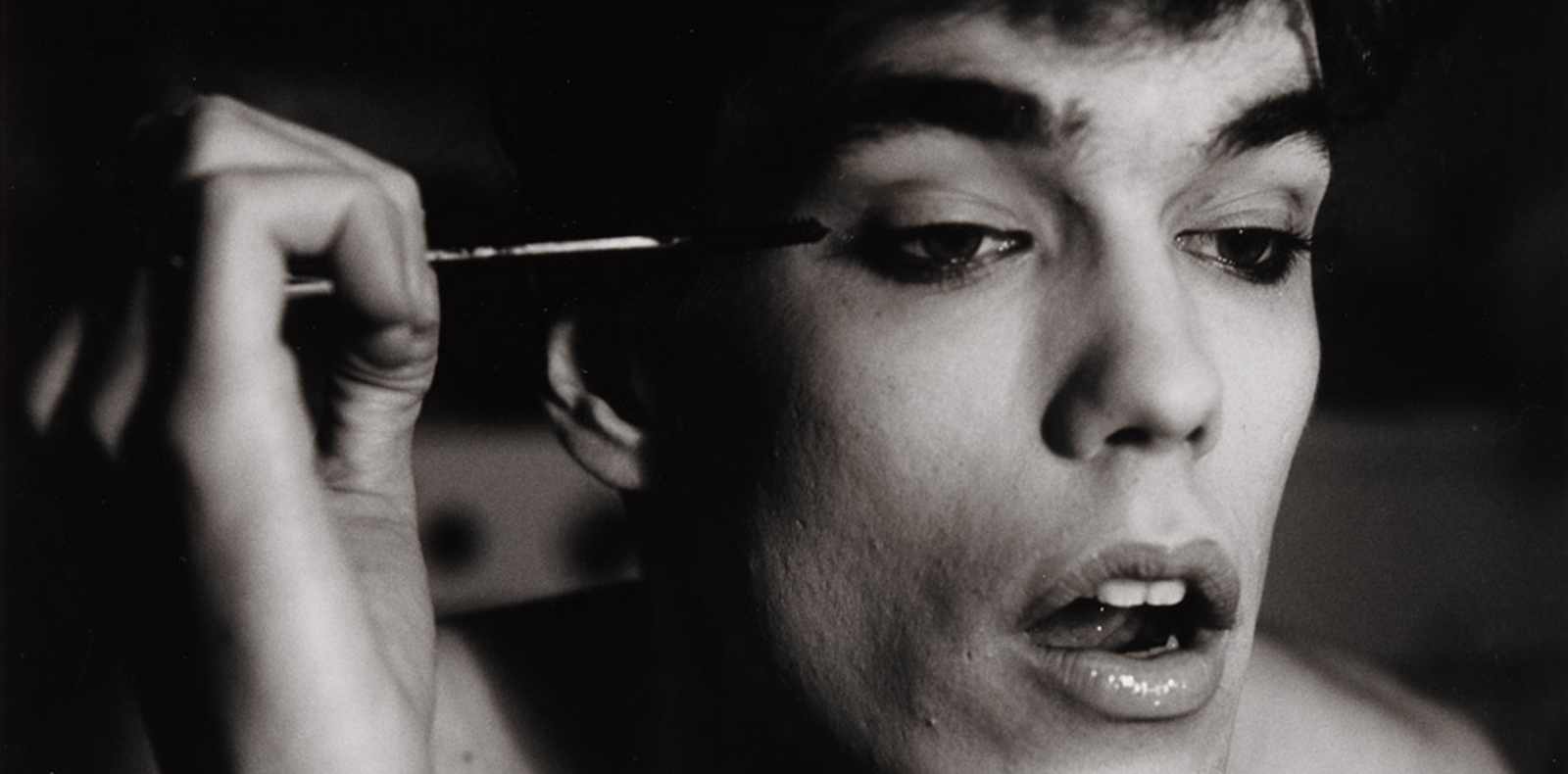

Portrait Jean-Baptiste Mondino,

Styling by Rebecca Bleynie.

We were expecting a femme fatale. But it was a little girl we found in the studio. Everything amuses her. Trying on an extravagant Saint Laurent jacket or falling gracefully onto a pile of mattresses for JeanBaptiste Mondino’s camera. Seeing her like that – radiant, mischievous and twirling around – it’s hard to believe that doctors once told her that she would never walk again, let alone sing. In 2003, Melody Gardot was riding her bike in her native Philadelphia when a Jeep came out of nowhere, knocked down the then 19-year-old and shattered her body. Coma. Broken pelvis. Dislocated jaw bone. Memory loss. She spent 18 months in hospital. And it was music that would help her learn to live again. “After the accident, I had to reconstruct myself completely. I was taught to see again and to hear with hearing aids. My body had to be completely reprogrammed. And music therapy was at the core of the healing process.” Working on songs helped her memory. Playing the guitar was physio for her fingers. Singing taught her to form words. Music didn’t just help her to recover but turned her into a jazzwoman who transcended her broken body through art. Just like the painter Frida Kahlo, after her terrible accident in a bus. Since then, Gardot has released five studio albums filled with a hybrid jazz that mixes borrowings from fado, bossa nova and gospel. And in the blues of her voice there's something of Dusty Springfield or Norah Jones. A saudade that tightens the chest.

When she speaks, it’s in a whisper, when she laughs, it’s peal. She quotes Siddhartha Gautama, the founder of Buddhism, chain smokes (“I don’t smoke that much!”) and switches between French and English like a swan between land and water. She reminds us of Lauren Bacall. Or Kathleen Turner. Her new album showcases live recordings, a double disc for which she listened to over 300 concerts in search of the magic moments. A spellbinding and sensual album in which Gardot redraws her repertoire with her everso-slightly veiled voice. All that in the venerable ambiance of old European concert halls whose souls she swears she can feel. “When you make a sound, it carries on to infinity. Sound is a vibration. Vibration is energy. All of that survives in space long after we’re dead. When I walk on stage at the Wiener Staatsoper, I can feel the footsteps of Chopin and Rachmaninov.”

And when she sings in Vienna or Warsaw, she can feel the breath of her Austrian and Polish ancestors on the back of her neck. “Do you think I’m crazy?” she asks on seeing our incredulous expressions. “Of course not!” we chorus. Just deliciously eccentric. “It’s just that my mind is more open than most people’s,” she declares. “I have a bit of supernatural take on life. For a moment, I went over to the other side. Since then, I can feel the presence of the departed. I’m very sensitive to it.”

“After the accident, I had to reconstruct myself completely. I was taught to see again and to hear with hearing aids. My body had to be completely reprogrammed. And music therapy was at the core of the healing process.” Music didn’t just help her recover, but turned her into a jazzwoman who transcended her broken body through art.

On the cover of her new album, Gardot stands on a stage wearing only a guitar. “For me an album cover is like a movie poster. I wanted an image that was pure femininity, which could please a sculptor. I went through a lot of suffering. But managing to stand up nude on stage carrying a guitar is a victory.” Her detractors sometimes criticize her for being too beautiful, for posing nude on album covers (she’d already done so for the cover of her fourth, The Absence) or for music they consider too safe. Criticisms that are like water off a duck’s back. Her only compass is her music and the audience that keeps her standing. “If today I can practice a sport, and move around 90% of the time without a cane, it’s because of the love and support of my producers, record labels and above all my audience who have always believed in me. Otherwise I wouldn’t have made much more progress than I did in the hospital.”

For a year now, Gardot has been living in Paris. To get away from the current “Trumpery”? To be closer to a continent that shows her more love than her native soil? “No, for love. It was love at first sight between me and Paris the first time I came. I’m so happy here.” Even if the winter here isn’t good for her and time goes too quickly. “I’m sure it’s the American in me, but crossing the Pont AlexandreIII or catching a glimpse of the Eiffel Tower when I’m walking the dog at night, it does it for me every time!” For the moment she’s settled, but this summer she’ll leave on tour again. “When you’re touring you live in a bubble. Then, at the end of the tour, the bubble bursts. You’re like an astronaut coming back to Earth. You need a certain amount of time to recover.”

We’re not going to find out anything about her private life. Or at any rate very little. All we learn is that someone is waiting for her at home “with a nice hot soup.” The profession isn’t compatible with a successful personal life? “Well, I don’t have child…”, she reminds us, conscious of the sacrifice involved in the Bohemian way of life, however chic. “I realize my life is a bit weird, very different from someone with a nineto-five job,” she admits, before adding, “But it’s a blessing to be able to travel.” Self pity is clearly not the house style round here. On the subject of style, hers is elegant but sober. She prefers black (like Piaf, who she amdires), hats (“It helps with the lights on stage”), and dark glasses (which she wears because of hypersensitivity to light), behind which you can still see her eyes twinkle when we talk of jam sessions or other musicians. In age when most albums are composed alone in a bedroom on a Mac, Gardot’s music is by nature a dialogue between several people. “Today, technically, you can play, accompany yourself and record yourself alone. But where’s the fun in that? Playing with yourself has a name,” she ironizes, while making the gesture. “Collaboration is part of my life. In Philly the music scene is like a family, but it’s competitive nonetheless. The best musicians leave for New York. Here it’s more fraternal. And there’s a lot of jazz in Paris. And I’m just blown away by the quality!”

At the end of our conversation, we hope to take away a bit of her strength and her enviable and inspiring serenity. What does it matter if it’s based in “healing” musicality, a drastic diet (macrobiotic) or cosmic spirituality? Of course there are difficult times. And her body is still shattered. To prove it she stands up and cracks her hip in our ears like the splitting of a plank of wood.

Gardot isn’t sectarian about her music, and regularly allows herself a few outings into French variété. She’s done a cover of one of Barbara’s more despairing songs for a girls’ compilation (Elles & Barbara), she’s sung duets with Eddy Mitchell and Juliette Gréco and preformed with the trumpet player Ibrahim Maalouf, on a bossa reprise of Dalida’s J’attendrai. “I’m very curious because I wasn’t able to finish university as a result of my accident. I still want to learn, be it another language, another way of cooking or of making music. It stimulates me. I want to become a better version of myself. I don’t want to end up like certain bottles of wine where you look at the label and say, ‘Shame, it’s gone off!’”

At the end of our conversation, we hope to take away a bit of her strength and her enviable and inspiring serenity. What does it matter if it’s based in “healing” musicality, a drastic diet (macrobiotic) or cosmic spirituality? Of course, there are still difficult times. And her body is still shattered. To prove it, she stands up and cracks her hip in our ears like the splitting of a plank of wood, while telling us how her jaw still sometimes blocks in the studio during takes. “For a long time I hated my body, because I was constantly suffering. But now I look at it like an old Mercedes with chrome bumpers. It costs a fortune to repair, it breaks down all the time, you can only use it once a week, the seat leather is starting to crack – but nonetheless it’s mine.”

Melody Gardot, Live in Europe (Universal Music/Decca), out now.