20

20

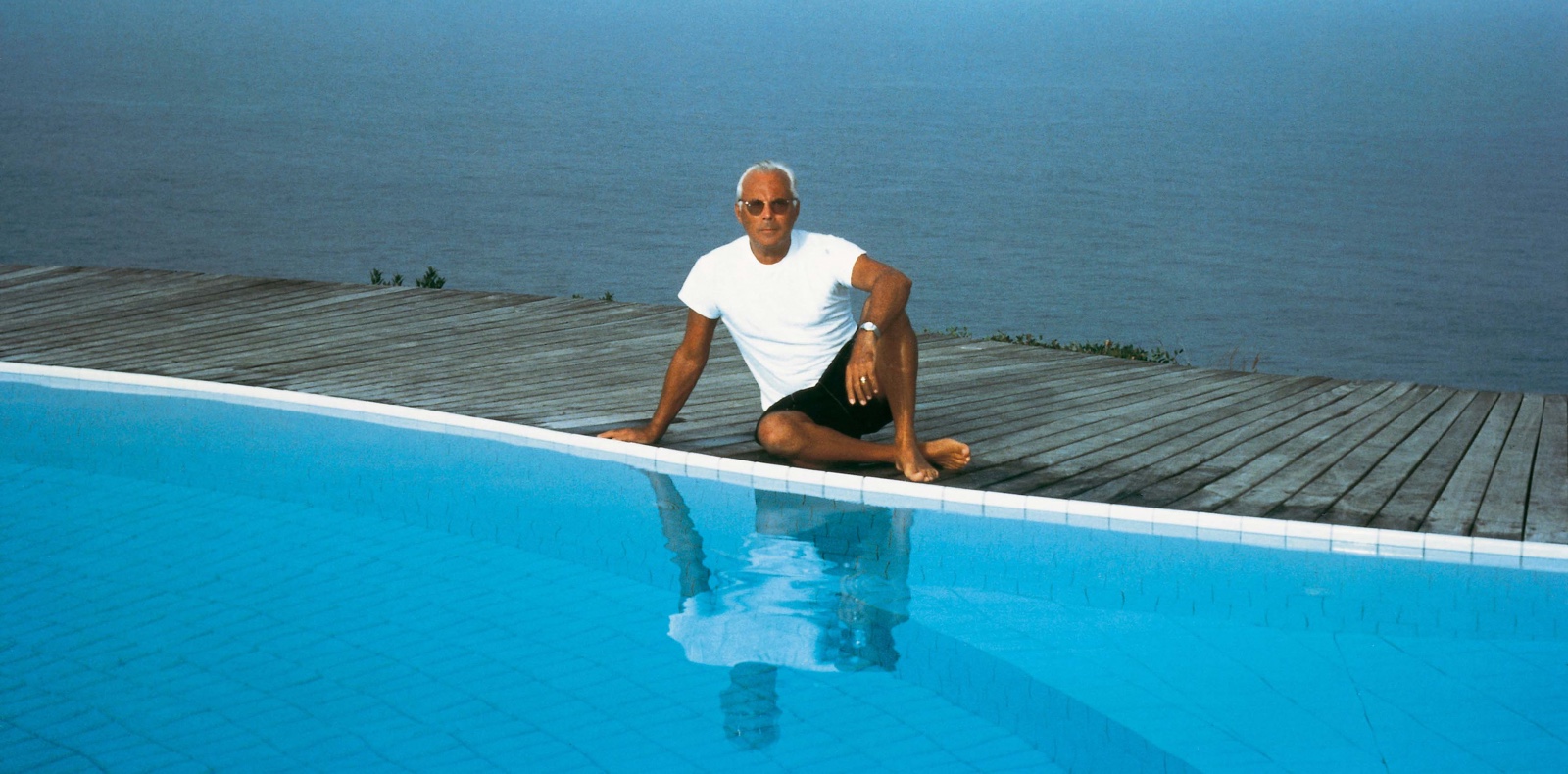

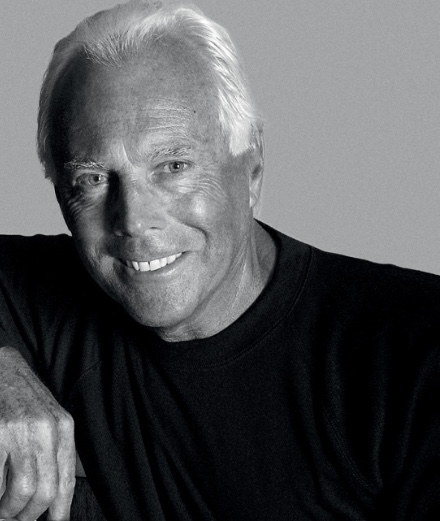

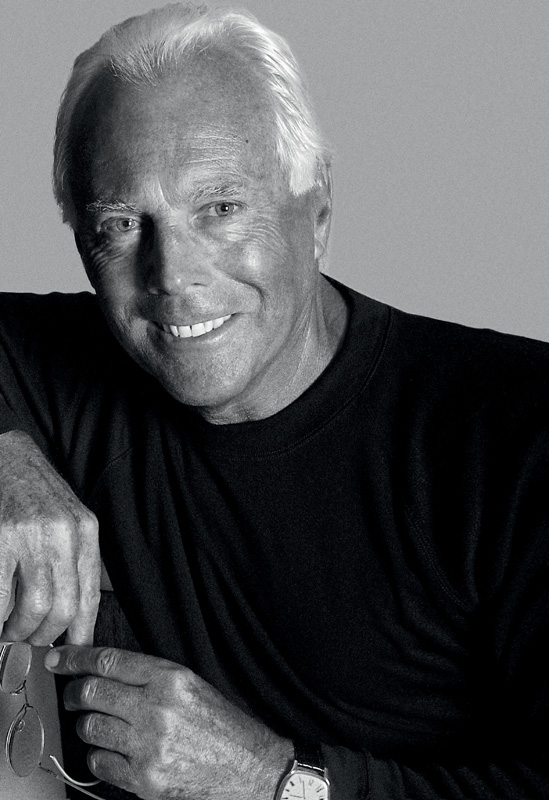

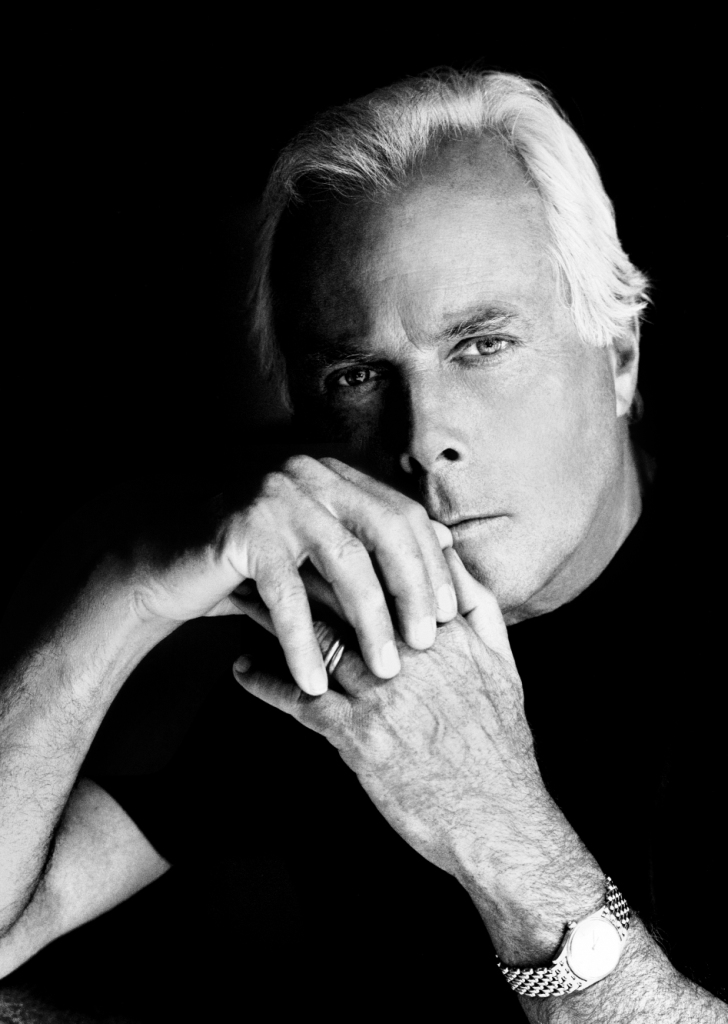

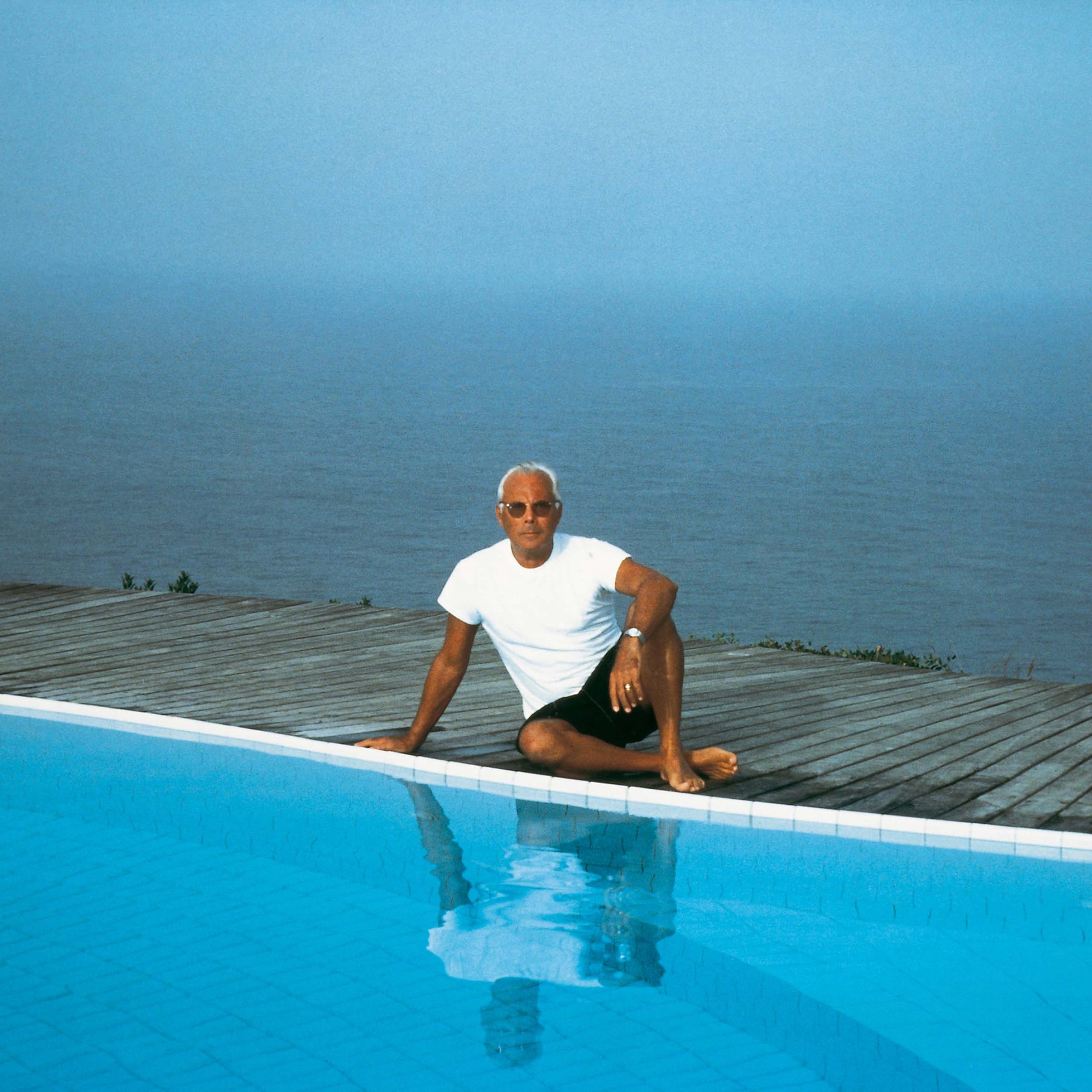

Giorgio Armani : “Luxury cannot and must not be fast.”

Over the course of his long career, the celebrated Italian designer, today head of a global fashion empire, has frequently proved himself a precursor. Today, as COVID-19 changes the face of the planet, he is once again showing the way, offering his thoughts on how the fashion industry should slow down and shape up.

Propos recueillis par Delphine Roche.

Numéro: Tell me about your childhood, and why you initially decided to study medicine.

Giorgio Armani: I had the simple life of a teenager growing up in post-war Italy: a country much poorer than the present-day nation. In that climate, my mother was able to convey a strong sense of rigour and dignity, values that undoubtedly influenced me later on in both work and life. The decision to enrol in medical school was very romantic: I thought I would become one of those adventurous country doctors depicted by AJ Cronin in The Citadel, a novel that really impressed me as a boy. But I soon realized it wasn’t my path. Though with the current health crisis, this desire has resurfaced.

I’ve seen photos of your mother, who was a very beautiful, naturally elegant woman. Did she help spark your interest in fashion?

My mother was a beautiful, elegant woman, who could be sweet and strong at the same time. Rigour and dignity characterized her entire life. Her practical way to face and solve problems, even in difficult times, had a great influence on me. Seeing my mother wearing her jackets certainly sparked an interest in clothing. She was doing more with less, and certainly not dressing like a doll. The jacket had a function, but she wore it elegantly, and it gave her presence. She also influenced my idea of beauty as a harmony of body and mind, expressiveness, a certain form of grace – exactness. My mother possessed all these qualities.

Did you already feel, back then, that you were attracted to a completely different field?

I was fascinated by everything that revolved around beauty. It called to me. And I had many interests, like photography, art and design. Fashion was just a facet of a much broader range. When I came onto the scene, I had the technical background necessary and a certain maturity, which led me to introduce myself into the dynamics of this world with passion and dedication. I can now say that I wouldn’t have wanted to do anything else, thanks to the possibilities I had to dive into all of my passions.

What was it like moving to Milan to work for La Rinascente?

Milan is the city where I chose to live, a city that welcomed me, understood me and has always been a source of inspiration ever since my first job at La Rinascente, where I was dressing windows and working as a buyer. I got to observe people, and that was an invaluable lesson. Milan at that time was a bursting, innovative city, and people were constantly on the lookout for something new.

What did you learn at the time through that experience?

I became passionate about fabrics and shapes through my experience at La Rinascente. Shortly after, I had the privilege of becoming an apprentice to the great Nino Cerruti. That’s where my career took off. It was Cerruti himself – to whose foresight I owe a lot – who asked me for new solutions to make a suit less rigid, more comfortable, less industrial and more tailored. It was then that, by de- constructing the jacket, I made it come alive on the body, using non-traditional fabrics.

Did you already set yourself ambitious goals back then? Or did success come more haphazardly?

If your passion is authentic, you never have a plan at the beginning. It was all about expressing my ideas. Everything started with the encouragement I received from my partner Sergio Galeotti, who had faith in me and pushed me to forge ahead. “Be yourself, believe in your vision, regardless of any criticism,” he said. It’s what I’ve always tried to do, and the results have been surprising. Today I’d love to show him what we ultimately achieved. We started out so small – I’m sure he would be amazed.

You established your company in 1975 and started with menswear. Did you feel there was a lack in menswear back then, or did you design something that you would like to wear yourself?

Back then, I saw men around me wearing stiff jackets that concealed the body and looked more like cages than anything else. I was looking for the exact opposite: clothes that created ease of movement and comfort. That’s how I came to create the first unstructured jackets, getting rid of lining and padding. Bit by bit, I also changed the arrangement of the buttons and modified the proportions, a process that radically transformed the garment at a time when men were exploring softer ways to be masculine. It was a moment of deep change, and I was part of the wave.

Very quickly, your suits were praised as a revolution in menswear. They set a new standard of modernity, and became symbolic of the spirit of the times. Were you surprised by that? How did you go about designing your famous suit?

I’m an extremely pragmatic creator: first and foremost I look at what’s around me. I did so when I created those famous suits, looking at what men of my age – I was 40 at the time – in my immediate environment wanted to wear, which wasn’t their fathers’ suits. I wasn’t surprised by the success, to be honest. I felt like I was dressing my generation with something relevant and timely.

In American Gigolo, Richard Gere made your work iconic. What was it like working on the costumes for the film? Did you imagine the impact it would have on culture?

I remember my enthusiasm for the idea of this collaboration. Paul Schrader, the film’s director, sensed the newness in my work, the new idea of masculinity, and thought it was perfect for Richard Gere’s character. Richard, in turn, brought it all to life with his lean, toned body and sensual moves. He was, quite honestly, stunning. The experience was crucial for me on every level. It made me understand the powerful impact celebrities can have on the public. People identify with them and are inevitably affected. Nobody could have imagined the movie’s success. It left its mark on the 80s, and became an im- portant medium for my fashion.

Your suits became even more of a symbol of the times when you dressed women in them. While Yves Saint Laurent had already put women in suits, yours was a very different version, more about power and comfort than fetishism and seduction. What was your intention?

It was my sister Rosanna who gave me the idea. Basically everything began with a request from her. She and her friends wore jackets I’d designed for men but wanted them adjusted to their bodies. So I set to work on women’s jackets and created styles with a simple and soft shape that allowed freedom of movement and unaffectedness – jackets as soft as cardigans, both powerful and feminine. It was a time when women were making strides in the workplace; I was offering them a new way to look, a new way of being. It was all comfort, power, femininity, ease.

In the 80s, you also diversified your offer into jeans, glasses and accessories, before opening your first restaurant in 1989, which was very new, after which you brought out Armani/Casa.

From the very beginning, I had this idea of creating a lifestyle, where many different elements would come together according to my vision and aesthetic, reflecting my style in areas other than fashion. Armani/Casa is the component that completes my all-encompassing vision as designer. Furniture seemed to me to be the logical development of this thinking, and I wanted to go into interior design long before the official launch of the range. The decision was also motivated by the fact that, as is often the case when I start my projects, it wasn’t easy for me to find the type of furniture and accessories that met my needs. It is a project that’s very close to my heart, and this year marks its 20th anniversary.

Milan and northern Italy have been very severely hit by the coronavirus. How has this affected you and all those you work with in the region? I’m deeply touched by this tragedy. And I have to say I’m impressed by the way in which we as a country have rallied round the health and other workers who are battling this situation. Luckily none of my collab- orators has been affected, but Italy has, and this makes me sad.

During Milan fashion week, you decided to do a digital show in order to protect the health of your team and of fashion professionals. It was a decision that wasn’t necessarily well received at the time…

Showing behind closed doors was an urgent safety measure, and it all felt awkward, and in a certain way surreal. A show is a public moment in which the designer shares his vision with the audience, so holding it behind closed doors diminished the experience for me too. But it was a necessary decision: there are moments in which the welfare of those around you – and this included my collaborators as well as my audience – is more important than anything else. It was the right thing to do and I would do it again, regardless of any negative comments.

Now, in an open letter in WWD, you’re calling for a deep change in the fashion industry. Designers have been complaining about the crazy pace of fashion for some time now. How did we even get there?

The decline of the fashion system as we know it began when the luxury segment adopted the operating methods of fast fashion, mimicking the latter’s endless delivery cycle in the hope of selling more, yet forgetting that luxury takes time to be achieved and appreciated. Luxury cannot and must not be fast. Fashion needs to slow down and produce less but better, and this is the perfect moment to do that.

You mention the idea that high-fashion pieces should be made to last. Do you feel that the very essence of luxury and beauty has been lost in the effort to make high fashion more “democratic”?

Democratic luxury is a contradiction. Luxury has been sacrificed on the altar of profit. Beautiful things made with the utmost care and that are meant to last come with a certain price, but they won’t be thrown away the following season. Which, by the way, suggests a more sustainable way of shopping, which is less dam- aging to the environment.

Is it fair to say that democracy, in the field of fashion, has too often resulted in mediocrity – an avalanche of cheap products and T-shirt collections?

If democracy means for fashion to be more focused on the real needs and desires of customers, then it will not result in mediocrity but rather fashion will become better and more meaningful. Personally I will be making every effort for this to happen.

If high fashion has had to adopt the pace of fast fashion, was this driven by customers or by retail?

They say it’s the customers, but I don’t think that’s correct. The senseless speed of fashion, with the warped turnaround of trends and collections and an arbitrary system of renewal, was mainly driven by certain stores, and became the dominant mind-set. This has now been proven wrong, and we can fix it.

In your plea, you say that the collections should be aligned with the seasons. Thirteen years ago, Hedi Slimane made the same comment when he left Dior Homme. Why has such a sensible idea proved so hard to implement?

Maybe it’s just a matter of old habits that need to be shattered. The nonalignment between the weather and the commercial season is frankly absurd, and needs to be fixed. I have been working with my teams to ensure that, after the lockdown, the summer collections will remain in the boutiques at least until the beginning of September, as it makes sense if they are genuinely connected to the progression of nature’s seasons. We will do this from now on.

You also mention the use of cruise shows – which are obviously detrimental to the planet – and grandiose runway shows as very expensive communication tools. Do you feel that fashion has lost its way, not only businesswise but also ethically? That somehow it has lost touch with reality?

Indeed, it has. I think that fashion needs to rediscover authenticity and emotions after years of intense marketing, excessive communication and ultimately operating in a vacuum. We are now beginning to understand what true luxury is: the freedom to walk outside, to travel, to see our friends and loved ones. In this context, we may well have a very different attitude to luxury goods in the future. We may appreciate more the simple things in life, and so when we come to purchase items, we may well do so more thoughtfully, with more consideration, and appreciate them all the more for it. This crisis is an opportunity to slow down and realign everything, to define a more meaningful landscape, and ultimately bring fashion closer to reality.

Do you feel that, in spite of the global crisis that continues to arise from this pandemic, positive trends might yet emerge?

I think this pandemic has forced all of us to reconsider many aspects of our lives. And I do hope this leads to positive change. Personally, I believe that attention to the client is paramount, and I’m working in that direction, evolving and rethinking our approach. In fact, I have just announced that starting from June my Armani Privé Atelier in Milan will be presenting, by individual appointment only, a repertoire of styles, both from current and previous collections, that clients will be able to customize in terms of shapes and fabric choices. The next couture show, which will take place in January in my Milan headquarters, will be seasonless and include garments suitable for winter as well as lighter pieces for summer. With respect to ready-to-wear, I’ve decided to optimize time and resources by showing menswear and womens-wear together in September.

While wise people like yourself are questioning the industry, others just can’t wait for it to resume exactly the way it was, as a meaningless competition pushing for more collections, more grandiose shows. What would you tell these people, face to face?

This crisis can be an opportunity to learn from our mistakes, adjust what we were doing wrong, and review our priorities. Change is inevitable. Going against it is wrong.