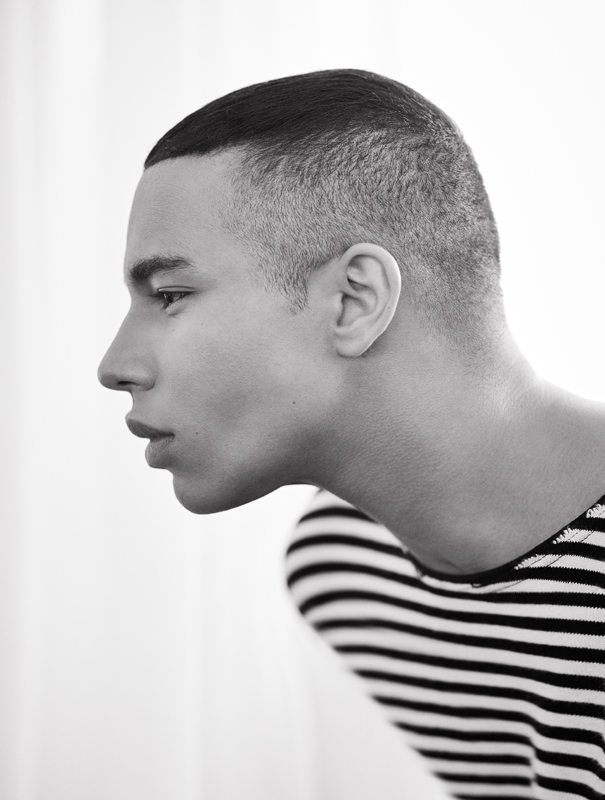

Numéro: Let’s start with your autumn-winter 2018–19 show, which was set in 2050. How do you imagine the future in 30 years’ time?

Olivier Rousteing: I’m not sure if I imagine the future... I imagine my collection. In any case I imagine strong women, more triumphant than ever, which is already happening. And a digital world of holograms. The idea behind the col- lection was clothes that play with light, that you perceive differently depending which angle you see them from. A world where everything is faster and faster. It’s what’s happening now, and I think that in 2050 things will go even faster. I wanted to look to the future because I’ve had enough of fashion that constantly seeks refuge in the vintage. We’ve arrived at a point where the cards have been reshuffled, and the new generations are challenging the older ones. My collection was born of this observation.

At the Coachella festival you dressed Beyoncé, whose stylist wanted a military theme. And a few years ago you came up with the idea of the “Balmain Army.” Moreover certain critics have cited the movie Mad Max with respect to your last runway show. Where does this fighting, con- quering spirit come from?

It came over the course of the collections. When I was appointed ar- tistic director in 2011, I didn’t have this desire to fight. At the beginning, I played the fashion game, and when I decided to be more faithful to who I was, I was heavily criticized, which affected me. That’s how the Balmain Army was born, female warriors with strong personalities. My muses are also like that. Fashion can sometimes be a fight where you have to push your ideas all the way to the end. Today I’m not so much at war, I’ve become much calmer.

“When I started using it, a lot of people criticized me: “It’s vulgar, how can you expose yourself so much?” But people need reality.”

During the runway show there was a T-shirt marked “We are the new generation.” You became artistic director at Balmain at 25, and today creative types in all fields are finding success in their 20s. How do you view this youth power grab?

I’m very happy to see all these young people who are doing all these things. The difference for me is that I was young in a French luxury house with a strong heritage and history. When you have a heritage to preserve, you have to satisfy the critics and attract new clients without frightening the old ones. When I started, I tried to please everybody. Then I took a step back, and tried to please myself. Moreover, what the critics and the fashion élite like isn’t necessarily what sells. If I’d followed their advice I would have risked being out of a job three seasons later. [Laughs.] For the golden rule in fash- ion is that you have to sell, and it’s also my rule. I am indeed part of the new generation, and today Anthony [Vaccarello], Virgil [Abloh] and Demna [Gvasalia] are in the same situation as me. Nowadays I don’t feel quite so alone.

Very early on you started using Instagram, which has totally reconfigured the whole fashion business. Did you anticipate such a radical change?

The Internet age frightened everybody in fashion. But I’m from a generation who thought it was great that you could buy clothes in just one click on the web. And I used Instagram as a means of communication, waiting for the moment when everything would naturally converge on the same platform – sales and communication. When I started using it, a lot of people criticized me: “It’s vulgar, how can you expose yourself so much?” But people need reality. We don’t just need to buy things, we also need to feel a connection with other human beings. Today I’ve stepped back a little, because some of the spontaneity has gone from Instagram. Everyone has understood that business is now done through communication, and firms specialized in strategy have taken over social networks. I feel that it’s something of a backwards step, so I’m not terribly convinced where the future of Instagram is concerned.

Beyoncé, Rihanna and Kim Kardashian are part of your story. Have you become used to having them as friends, or do you sometimes wake up in the morning thinking to yourself, “Oh my god, it’s incredible”?

Kim and Rihanna are very close friends of mine. Beyoncé and I aren’t friends, but we have a relationship of mutual respect. I always say to myself that I’m incredibly lucky to be so close to them. I realized it at Coachella, when Beyoncé invited me to watch her rehearsals. It was amazing to see her singing her hits with just me as an audience, while making her final checks with the technical crew. I have the feeling that something is really happening in my life which I have to be conscious of. But let’s not forget that when I decided to go for hip-hop and R’n’B, the fashion world came down on me like a ton of bricks. I’m not against criticism, all points of view should find their expression. But I never demean others, whereas I’ve felt that people were demeaning me. Today nobody’s shocked anymore, but I remember in 2013, when I did a campaign with Rihanna, interviewers would ask me if I was really sure that the world of luxury ought to associate with hip-hop. People also said I’d become Americanized, whereas I adore France, and a large part of my fashion references are French. What’s more, Pierre Balmain dressed Audrey Hepburn, Josephine Baker, Brigitte Bardot and Dalida, some of whom were already controversial, so it’s not like I invented anything. Being close to music is something that Gianni [Versace] had already done before me, as had M. Saint Laurent. The Bains-Douches nightclub predates me by decades – I just followed a Parisian tradition. Except that recently people have rather tended to mistake Paris for Neuilly, or to focus only on the tastes and lifestyles of those living in the 16th. Let’s not forget how cosmopolitan Paris is and that many of those responsible for its glory were foreigners. So yes, I adore the U.S., but I’m also very French, and proud of it.

“When you don’t know where you come from, you’ve no limits in imagining where you might go. I’m a survivor, a warrior.”

You even declared your love for Emmanuel and Brigitte Macron. What is it you like about them?

The fact that they didn’t follow the usual path for French politicians is something that speaks to me a lot. During a dinner at the Élysée Palace, I was at the main table opposite them, and I really liked their spontaneity and their kindness. They show respect and haven’t forgotten where they came from. Politics, even more than fashion, is a world that’s cadenced on protocol. I like the fact that they’re changing those codes in France, thereby proving that it’s possible. Even their relationship represents something new. It’s a story for our times. I find it very touching that the love they feel for each other is possible and that, despite its unusualness, their relationship didn’t prove to be an obstacle.

In January you launched a capsule collection of evening gowns which celebrates the craftsmanship of the Balamain ateliers. How do you negotiate the potential divides between tradition and innovation, craftsmanship and social media?

The fashion world has gone from being very conservative to being obsessed with millennials and their desires. But it’s not enough to design a pair of sneakers if you want to please them, the approach needs to be much deeper. While I’m a fan of digital technologies, I want Balmain to remain a traditional French luxury house. On my Instagram account, I’ll just as easily post a pair of jeans as an haute-couture dress. If I’d only done haute-couture gowns, the business would have sunk under the weight of dusty irrelevance. And if I’d only done jeans and digital content, we’d have become a gimmick. I do a semi-couture line of evening dresses because it’s still what people dream of. And at the same time, I use social media to transmit this image to future clients. Lots of young women come to the boutiques with their mothers: while the daughter is buying a zip-up blouson, the mother comes away with a six-button jacket. Our offer is transversal, it touches different generations. Things change quickly, but that doesn’t mean you can allow yourself to slip in thought or quality. France is known for being a research lab, from cuisine to medicine to fashion. We mustn’t only think in the short term or concen- trate only on the immediate, we mustn’t lose what it is that brings a unique quality to the things we do. We could make bomber jackets or sweatshirts with logos, but that’s not what’s going to bring glory to France in the next few decades.

How have things changed for you since Balmain was bought up in 2016 by the Qatari group Mayhoola for Investments?

I now have more possibilities for self expression. The new management respects me, they like luxury and they challenge me. So together we can go even further. They give me real freedom of expression, and I think that it’s often that which is missing in fashion today. My personal life hasn’t changed much because I’ve always worked a lot – I get up early and work till late. I’m never bored, there are always boutique openings and various projects.

“I’m anchored in two sets of origins, one that I know and the other which I don’t.”

These days people often say that Virgil Abloh is the first black designer to take the helm at a big Parisian fashion house, whereas you got there long before him. How do you feel about that?

I heard that too, and I was a bit surprised. I find it interesting... It’s probably because I’m mixed. But that’s a little bit the story of my life: for the blacks I’m not black, for the whites I’m not white. In any case, I’m very happy for Virgil, and his success opens new doors for young people, for people who come from all sorts of different backgrounds. But the real question is does the fashion world understand what’s happening? I get the impression that people in the business think they have to like Virgil or streetwear because it’s the trend right now. I’ve seen a lot of trends over the past eight years. When I started out, I couldn’t wait to be old because it conferred a certain legitimacy. Whereas now being young is a form of legitimacy.

In an interview on CNN you argued in favour of ethnic diversity in fashion shows and shoots.

Ethnic diversity in fashion is something that’s finally happening and I’m pleased about that. But what hurt me a lot at certain times in fashion was that sometimes people claimed their take was artistic or modern when in fact it was simply archaic and racist. I was very shocked by that. It’s not enough to do oversize and Neoprene to be modern. You can’t defend something that’s disrespectful. People called me “vulgar” because of some of my casting choices, whereas they’ll say that someone who picks only skinny blue-eyed blondes is modern. If that’s the Holy Grail sought after by the fashion élite, then I’d rather not be part of it.

I’ve heard talk that there’s a film coming out about you in 2019.

Yes, a director has been shooting a movie about me for the past year. It’s about both my professional and private life. It will be a message of hope for many young people. In the movie I show people an Olivier they don’t know.

You often talk about your childhood in Bordeaux as an adopted son. Is it important for you to remain anchored in the real?

I’m anchored in two sets of origins, one that I know and the other which I don’t. The one I know is my parents in Bordeaux, who I wouldn’t call conservative but certainly very French, who taught me wonderful values. And then there’s the origins of my birth, about which I know nothing, but which give me an appetite for diversity and to open France up to a far-off and unknown world. I’ve never met my biological parents, so I have absolutely no idea where my skin colour comes from.

Does this missing part in your past motivate you to go further?

Yes, because I’m afraid of nothing. When you don’t know where you come from, you’ve no limits in imagining where you might go. I’m a survivor, a warrior. When you’ve been through a lot of pain, nothing hurts you anymore. When I was little, the other kids called me “the bastard” because I was black and my parents were white. Even in my own family people were very critical. When my parents decided to adopt a non- white child, my grandparents didn’t understand it. Other people’s views of me have always been very hard. I don’t want to sound like a victim because that’s not me – you know me. But today when someone calls me vulgar or too sexy, when people make fun of me because of a few selfies, I don’t care. I’ve been through far worse.

Your ability to remain sincere and accessible is something that’s become very rare in the fashion world, where designers tightly control their image through armies of press assistants.

I think honesty always pays off. I can’t live a lie. Everything might stop tomorrow, so every day I try to be myself. I’m too frightened of waking up one day and saying I tried too hard to please others, that I didn’t express who I was. When I was young, I wanted to own my skin colour and my white parents, and later I wanted to own my homosexuality – I didn’t want to hide who I was. And I still have absolutely no desire to pretend to be someone else today.