22

22

How are Kim Jones and Dior committed to help protect the oceans?

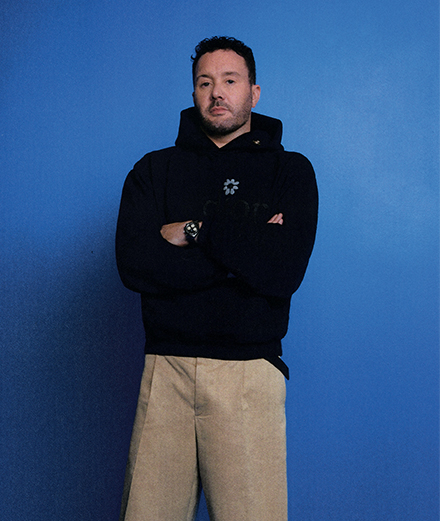

For Numéro, designers Cyrill Gutsch and Kim Jones discuss the future of the oceans and the issue of biodiversity, at the heart of the Parley x Dior collaboration, unveiled early this summer.

Interview by Delphine Roche.

Published on 22 August 2023. Updated on 20 June 2024.

Eleven years ago, designer Cyrill Gutsch founded Parley for the Oceans, a charity dedicated to preserving the sea from plastic pollution by collecting and recycling it. Close to the worlds of art and fashion, the organization is putting its money on design as the spearhead for eco-responsible innovation. In this context, Dior Men is currently showing its second collaboration with Parley for the Oceans, a recyled-plastic beachwear collection designed by the label’s British creative director, Kim Jones. For Numéro, the two men sat down to talk about the future of the oceans and the question of biodiversity, subjects that are of great importance to both of them.

Numéro : This is your second collection of men’s beachwear together. How did your collaboration come about?

Kim Jones : Growing up in several African countries, I had the chance to discover the world when it was in rather better health than today. I love diving – I travel the world to go and see rare and wonderful fish and animals. I really love what Cyrill does and what Parley for the Oceans stands for, and we thought, well, in these big brands like Dior, it’s important to have a conversation about sustainability. It just seemed logical, so we started the discussion. We’ve now reached a critical moment where things need to move, but a big ship like Dior takes quite a long time to turn around. So we’re doing it collection by collection. The Dior Essentials collection uses 80% sustainable and recycled materials, while in this capsule collaboration with Parley for the Oceans we’ve reached 96% recycled plastic.

Cyrill Gutsch : First of all, it’s important for me to work with someone who really loves animals. You can’t show empathy for the cause we represent without feeling it, without knowing the beauty of the sea and being in love with it. So that’s the number-one reason I love to work with Kim, besides his being a fantastic designer. We were talking about how wonderful octopuses are just now – there’s something that connects us deeply. We approach it from very different angles, but we meet on a very pragmatic level of actually making things happen. In my world of environmentalism, there’s a lot of talking, there are a lot of ideals. You can try to dream of a world that is non-toxic, non-harmful, but if you’re not taking the steps to get there, you’ll never change the way we do business – and the way we’ve done business these last few decades has created a nightmarish scenario. I feel the approach of going item by item, collection by collection, is a very good one, because every collection is a lesson for the whole organization. Things take longer, things cost more, things need to be communicated – it’s way more effort to make things differently. And without a strong creative champion on the organization’s side, there’s no way for us to achieve that. So that’s why Kim and I are working together, in my eyes.

Sustainable development is generally presented as problem to be solved, but you show it can also be a source of renewed creativity.

KJ: I think a customer will spend a bit more money on something they know is better for the environment. A store such as Dior is expensive anyway, so it’s not like you’re going to question a few more euros. The first collection was very well accepted by the consumer, so it’s great to carry on the relationship with Parley For the Oceans because we can develop it further, we can look at different product categories, such as leather goods. Obviously, it takes a lot of time and research to achieve the quality needed for a Dior piece. But Parley worked as fast as possible to make it happen – it’s a really impressive organization. One of the advantages of the luxury sector is that volume is relatively limited in comparison to mass producers. And at LVMH the question of sustainable development is treated very seriously. It’s something my teams take particularly to heart, among them Natalia Culberas-Cruz [director of sustainable development], Rémi Macario [product coordinator for sustainable development] and Lucy Beeden [design director]. These are people who also like to travel, ski, or dive, and who, like me, are horrified by the current state of the planet. It’s important for us that future generations can see all the magnificent animals out there in the world.

CG: Protecting life is the new luxury really. And to that end, we always try to use the most appropriate materials. In the Dior Men/Parley collection you can say that each product fights our battle on the front lines.

“When I stop doing fashion, I’m going to do conservation full time.” Kim Jones

How difficult was it, using recycled Parley Plastic®, to obtain fabric that met the standards of Dior Men? I believe the research began back in 2019.

KJ: It took time, but, you know, it’s worth taking time to do it because then you can use it longer. When I saw the first samples and swatches, I was like, “Wow, you wouldn’t know that’s recycled plastic.” That’s an exciting thing for us, because it means we can think of designs in a much more fluid and natural way. For me, recycling plastic is such a logical thing, because it’s such a problem. I returned to Indonesia last summer for the first time since the pandemic. And it was so different. For example, you’ve got the entrance to Komodo National Park with its beautiful pristine beach on one side, but on the other it’s all plastic. I was with Kate Moss and everyone, and we just got bags and were filling them up with plastic, because that’s what we could do. It’s certainly not the fault of the people who live there since plastic washes up from everywhere. So for me it’s a big concern, because I love nature – when I stop doing fashion, I’m going to do conservation full time for sure. Life is divided into different chapters, and I’ve got projects that I work on and sponsor, for example the preservation of a rare monkey in Vietnam. When I started, there were only 500 left, and today there are over 1,000. When I’m not working, I want to be in nature, I want to walk through savannah or go underwater and see sharks, turtles, pygmy sea horses, all these beautiful creatures. It might sound very contradictory with what I do for a living, but I don’t think so. I know I can also help –I help a lot of different communities in Kenya, for example. These are the things I’m passionate about, and that’s the legacy I’d like to leave behind me more than anything else.

CG: I don’t see a contradiction here – actually I see the opposite. For me, it’s a very logical alliance, and I find that the criticism about luxury taking new environmental initiatives is wrong. I think we are taking a step now where we’re democratizing environmental protection. It starts from the top, because those at the top can actually make the biggest decisions, and they’re the ones who can master materials and do all the R&D and pay the higher prices. Because, let’s be realistic, our material is not affordable for most companies out there. Working with the luxury sector also means the products are not ending up in a landfill because they have a secondary market or because people keep them forever. So there are a lot of reasons why we work with luxury. Another one is that we create value, which you can later break down to the masses once there’s a new understanding.

KJ: It also helps you develop your technology so that it eventually becomes affordable and accessible to different sectors of the market. Starting at the top of the pyramid allows you to establish an icon, an example, and afterwards to democratize your material.

CG: Absolutely. Fashion and art are really our space industry, or our Formula 1. And fashion is one of those rare industries where the designer has so much power. In most businesses, designers have to obey more or less. For me, fashion is the last kingdom of design.

Is that your feeling Kim?

KJ: Well, you can come up with an idea like this and people will go, “Oh, but that’ll be expensive.” So it’s up to you to convince them. “I know it’s expensive, but clients are going to like it.” You have to trust your instincts. People were locked down for almost two years during the pandemic, so what do they want to do now? They want to go and see the world. When they start seeing the problems in the world, they want to help. Because everyone’s got compassion. People start petitions, for example. Everyone does this, everyone does that, and it filters through. But if I meet anyone powerful or influential, I always talk about the environment with them, and I talk about

the projects I do in Africa and Vietnam and the things I want to do in the future. And when addressing people who don’t quite understand, I always talk about it in terms of their grandchildren, because if you talk about their grandchildren not seeing what they’ve seen, that’s a sad situation. You know, in 20, 50 years, I might not be here, but I don’t care about that, because it’s important to fight for the world’s future.

CG: And time is an issue now. In the last ten years we’ve seen a rapid decline of life out there. And I see it with my own eyes – I don’t even need to look at the scientific stats. And the next five to ten years will mark another drastic jump. And we are so many people and we kill and we po lute. So now it’s about redesigning the source of that problem, which is materials. We’re in a material revolution, really, the same way we all experienced the digital revolution. Recycling is one aspect of that, and it will always play a role because nature is the master of recycling. The materials will change though. We want to hack cells, and grow things that we need instead of coming with our not-so-intelligent materials. It’s an evolution that we can steer and drive. Everything we do today has a very big impact on tomorrow; if we were to halt now and say we’re waiting for the perfect material, tomorrow would never come. We’d get stuck in the old. So we need to do everything we can today. And that’s what I learned at Parley. You know, if you just talk, nothing happens.

KJ: You’ve gone out and done it. It’s something I would think about, but I don’t have the technical insight for that. Though I have found the niche that allows me to work on and develop my passions outside of fashion. And one of my favourite things is taking people to places in the world they’ve never been to before – and then they get into it too. We’ve lost six percent of mammals and vertebrates since 1960. That’s a huge amount. But there’s still lots of wilderness left. In North America, particularly in Canada, or in Congo. It’s also about helping the communities to support it. It’s not ours to own, because we’ve done that before. My father taught me a lot about Africa. He lived there for 40 years and taught me racism was wrong, that everyone is born the same. He worked for the UN and found water for people where there was no water. But he wouldn’t do things that were about making people money; he did stuff that was really about supporting communities. Before he died, his last job was working on how to restructure and protect the forests that border the Sahara, so that the desert sand won’t encroach any further. He studied different types of oxides to cool the air, things like that.

Cyrill, you spoke about the materials revolution – what part do natural materials coming out of ecological agriculture play in that future?

CG: Nature offers so many resources that are more sustainable and renewable. How can we create the most amazing fabric out of cells retrieved from coral? How can we use 100-percent-natural fibre from Manila hemp?

KJ: And these resources can also help in medicine. There’s probably a plant or something out there that can help cure cancer.

CG: That’s a very important point. For too long, we’ve felt we know it all and that we’re better than nature. Sometimes we even thought we’d improved on nature. But the truth, as Kim just said, is that we’ve barely unlocked her secrets. There are so many natural wonders that could cure disease: enzymes, creatures, organisms out there that can solve problems we have or don’t even know we have. It’s a wonderful world. And for too long we’ve been too arrogant, and have just poisoned and killed. Now at last, let’s hope, we’re moving towards an eye-level relationship with nature and truly collaborating with these creatures.

KJ: Yeah. I mean, I’ve gone tracking in the Amazon. I’ve gone all over the world, and you talk to local people and they just show you a handful of plants and what they can do for their community. And that’s just the surface. So you have to go back to nature, it’s really important. Obviously you need to carry out proper medical studies, but the planet is here, and it has pretty much everything on it. What is it, like only five percent of the deep sea has been explored?

CG: That’s right, five percent. We know more about space than we know about the oceans We still don’t

know what all these creatures do down there. We thought there was no life in the deep sea, and now we’ve discovered there is. We know so little. We believe in science, but there is other knowledge. There’s indigenous community knowledge that we haven’t bothered to look at because they’re not writing scientific papers. But the truth is they probably know more, because they learn to trust in the knowledge of nature, which we still don’t understand from a scientific standpoint. So there’s something between instinct and human science – there’s a gap that needs to be bridged.

When you founded Parley for the Oceans, no one was yet talking about the danger of drought and the lack of water. Now everyone is conscious of the problem.

CG: Ten years ago when we started, people thought we were crazy. They were like, “This guy lost it.” Now is a very different moment – people have understood that there’s no hiding ground. You can’t imagine that you’ll live protected in a gated community: everyone will be impacted. And that’s why the pandemic we just experienced is a little taste of how powerful nature can be, you know?

Kim, fashion has to sell dreams. How do you reconcile that with environmental concerns?

KJ: Fashion is about the dream, but the dream has to be a reality, because it can quickly go from a dream to a nightmare. If you can incorporate some of this sensibility into fashion, you’re still creating the dream, but you’re also thinking about the future. If I’m doing a couture show, that’s my real dream, because that’s where we really play around with the codes of the house and can embroider and embellish. But there are also more practical things we can do in helping Parley and other such organizations to spread their message. If you go to Indonesia, the Philippines, or the Maldives, and you’re wearing your Dior, and you know that it’s made of plastic that came from the sea, that you bought something that is helping, then you appreciate it while being there. That’s a good feeling. And that’s one thing that clothes do – they make people feel good about themselves. That’s something I realized when I started at Dior. And if you know that the clothes you’re wearing also help the planet, it’s part of the dream as well.

Dior x Parley for the Oceans, available.