8

8

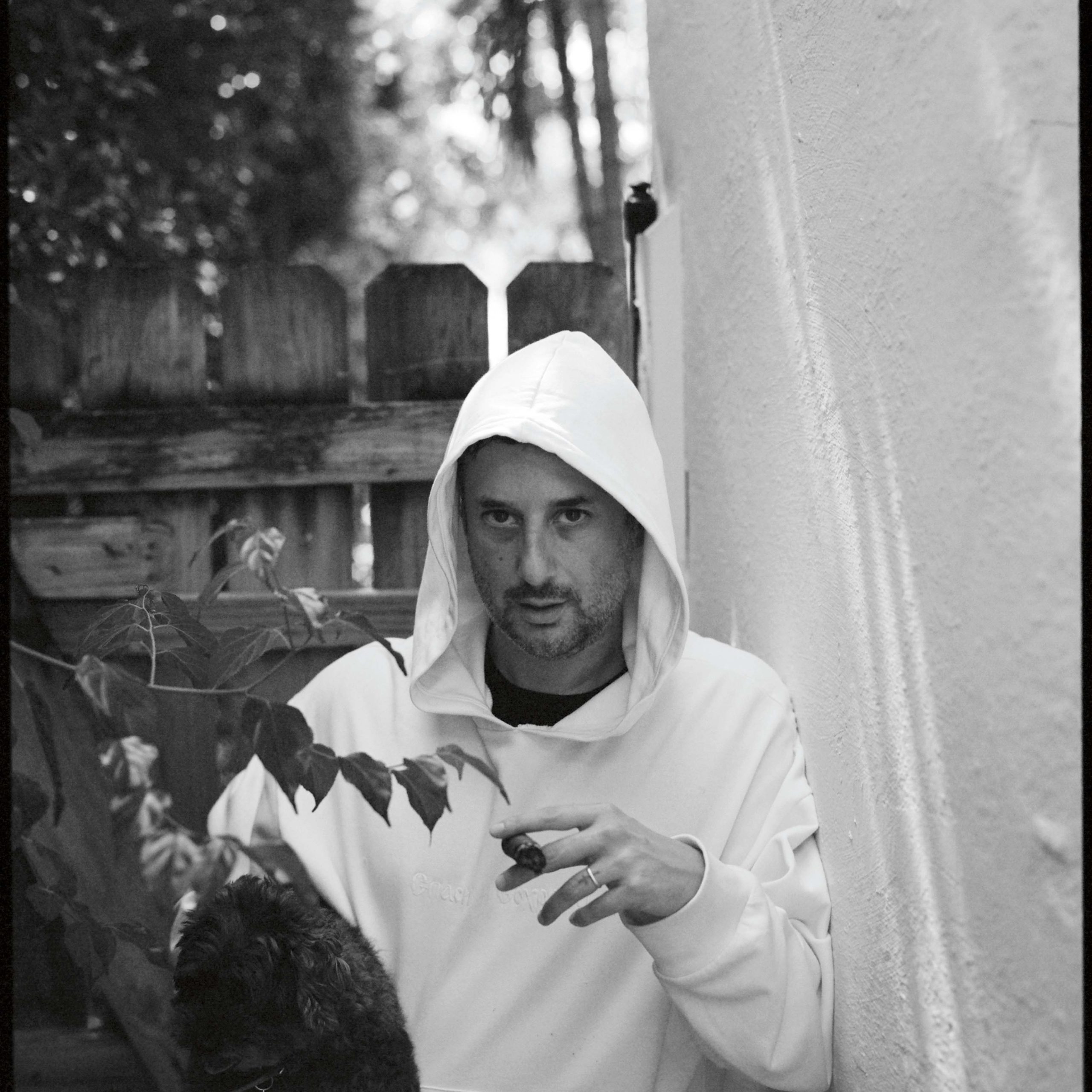

The Centre Pompidou honours Harmony Korine

Poet of teenage drifters and the dark side of America, the director of Spring Breakers, who was also the scriptwriter for Larry Clark’s Kids, is being honoured at the rather young age of 44 with a month-long retrospective at the Centre Pompidou. The exhibition will showcase all the diversity of his output, from poems, paintings and film to videos and advertising.

By Olivier Joyard.

Twenty years ago, when Harmony Korine first achieved fame as the hugely talented scriptwriter for Larry Clark’s Kids and the director of a strange indie film called Gummo, he would often fail to turn up to interviews, no doubt too busy taking illicit substances. Now in his forties and crowned with the success (unprecedented for him) of his 2013 movie Spring Breakers, the American angel-demon has become much more reliable. In an age when offbeat artists have rather a difficult time of it selling their new forms and ideas on the market, he has channelled his perpetual agitation into a flourishing creative force. Poet of a pop culture with its roots in the underground, Korine has almost become an institution, to the extent that Paris’s Centre Pompidou is currently showing a retrospective of his films, paintings, poems, music videos and adverts. It’s a consecration that’s thoroughly deserved for this indefatigable investigator of the American dream in all its darkest and most fascinating aspects.

Numéro : The Centre Pompidou is putting on a retrospective of your work, an honour usually reser ved for old people – yet you’re only 44!

Harmony Korine : Perhaps I’m a young old soul, but I’m okay with that. It’s the first time I’ll be able to see, gathered together in the same place, all the films, paintings, writings, photos, music videos, adverts and everything else I’ve done. A synopsis of my existence! Since I was a kid, I’ve had the impression that everything I do is connected and comes from the same idea. I’ve never really tried to find a precise meaning in all that, but a sort of coherence, yes. I’ve made art by letting my impulses speak, by having fun and creating chaos. I like that my work has a unified aesthetic, but I don’t believe there’s anything good or bad in art – even the not-so-good things have their value. The creative journey, the way you create, are just as important as the final result. My movies and paintings search for a certain singularity.

Your style is very recognizable, but it also seems to be constantly evolving. How would you define this “unified aesthetic,” as you describe it?

I try to experiment in different styles, but the heart of it remains the same: I manipulate truth, with the goal of producing a vibration that’s close to a feeling. A tactile feeling, or the idea of what’s real and what isn’t, of what’s true and what isn’t, of what’s manipulation and what isn’t… In fact everything becomes part of the same whirlwind, like a chain reaction.

At the beginning of your career, people identified you with the New York street scene because of the film Kids. Nowadays people tend to think of you as a man from the South. But you’ve also lived in California. Which bit of the US would you say you really belong to?

I feel like I incarnate the whole of America. I was born in a community in California, but I was brought up in the carnivals and circuses of the South. My father made documentaries. I grew up surrounded by bootleggers and kids who took part in rodeos, I ran into weird magicians. It’s an atmosphere I’ve kept inside me. I went to school for a bit in New York, now I live in Miami. In the past few years I’ve lived in Panama and Colombia. Right now I’m thinking of moving to Cuba. We’ll see. I get bored pretty quickly. I never thought of living in one place my whole life – I don’t really like the idea of comfort and familiarity with a place. What thrills me are landscapes, architecture, colours; I always want to know what’s round the next corner.

Hip-hop has become a major influence in American culture, as was clear in Spring Breakers.

The movie I’m making this fall has nothing to do with hip-hop or the South, but the one I almost made just before, and which has been postponed till next year, is called The Trap and is all about that. Music has been a big influence for me. Growing up in the South, in public schools, I was really exposed to it – I listened to groups like Three 6 Mafia and 8Ball & MJG.

Spring Breakers and the video you made for Rihanna’s Needed Me have a very strong aesthetic, both dark and wild. Do you think you’ve found your style?

In visual terms, everything is linked to a story and to a state of mind at the time. My next movie will be far from all of that. I’ve written a script called The Beach Bum, a stoner comedy reduced to its essence, without frills, like a song by Jimmy Buffett [a popular country-and-western singer], but perverted of course! Matthew McConaughey is in the cast, as well as Snoop Dogg.

Do you ever watch your old films? How do you see them now?

I rarely watch them… Every ten or 15 years I’d say. I like to leave them where they are, like children I’ve turned out into the world so that they discover it for themselves. After spending intense moments with them, I abandon them as orphans. I love them all in the same way. When I think of them, it’s more with respect to specific scenes, certain moments with the actors.

I well remember the crazy, tender bath scene in Gummo, when a small boy washes in dirty water. There’s also that wonderful bit in Spring Breakers with Britney Spears’s song Everytime.

Certain scenes become iconic, but it’s rare that you realize it when you’re shooting them. I still don’t understand why some scenes resonate and others don’t. What will stay with people in a movie often escapes me.

Do you write from life experience or from dreams?

I’d say a combination of both. In any case dreams are derived from life. I build my stories principally from visual inspirations, almost visions. A trip to Cuba or Colombia can inspire me. A woman in hair rollers and boxing gloves throwing punches at her reflection in the mirror – that excites me… I find the image weird, and start imagining the woman’s life, what her husband’s like, her job… At times I use photos. I never start without some kind of visual material.

And what about your paintings?

For the past five or six years, I’ve been working a lot on my pictures. They’ve taken over my life. Movies are a very collaborative medium where you have to play the game to get what you want. Art is more personal and direct. If I want to paint a larger person, or use a certain colour, well I just do it – no need to explain to an actor why I’m painting the corners of the picture red. At the same time, I get pleasure out of doing everything. Sometimes an idea comes and turns into a poem, other times it’ll be a painting or a film… I’ve always wanted to dance between different media.

“I’ve never had a serious problem with actors, even the stars – they all know I’m going to wreak havoc!”

When you were a kid, was your goal really to become a professional skateboarder?

When I was 13 or 14 it was my obsession. But before that I wanted to become a tap dancer after seeing a show with the Nicholas Brothers, who were Fred Astaire’s heroes. At one point I also wanted to live Buster Keaton’s life – he came from the circus. Then skateboarding came along, but I wasn’t good enough to go professional, and at 16 or 17 I changed tack and started developing ideas for movies.

You’ve no regrets?

There are things you’re not good enough at and there’s no point regretting them. I also wanted to slam dunk in basketball, but that never happened!

Your life as a young adult was very agitated – is that all over now?

My life is structured now, I’m not the same person I was at 20. Back then I was a crazy fucker. I didn’t give a shit about anything, I was always about to explode. Or I didn’t give a shit and yet cared deeply… you know what I mean? I was really involved in the work I was doing and yet, at the same time, I didn’t give a fuck. I went straight from high school to making movies, and I still felt all the anger of a skateboarder who fought with rednecks and got himself spat on. I spontaneously went for provocation. I’ve always hated being bored, but I didn’t know how to activate the off button.

Is this flame of weirdness still there 20 years later? Perhaps the problem today is the opposite – how to keep it alive?

The difference is that all my rage goes into what I produce. I’m the same person, but with the ability to control my private life… so as not to die! I realized that for my mental and physical health, I needed to live differently. But my work still comes from the same urgency. I’m still an aggressive experimenter, but in a different way.

America has always been your favourite subject. How do you feel about it today?

The country is what it is, like a permanent pendulum where everything swings but nothing changes. What’s different about me is that I never give in to the culture of complaining. I prefer that my movies give a feeling of the reality of America, rather than being didactic and explaining everything. We all know the problems. America is a double-edged sword, it represents the best but also terrible violence. The two go hand in hand.

The underground, of which you’re one of the heroes, is beginning to rub off on the mainstream…

I think that today there are no more subcultures or underground. It was different when I was growing up. Back then there were specific entities, places of power you could rise up against, identifiable forces of darkness. We knew where the system was. Today everything is more fragmented and globalized, there’s no more underground or above ground, the internet has accelerated everything and the only law is speed. The depressing thing about this situation is the uniformity of desires and the ceaseless commodification. Everything is corporate, we live in a plastic boredom, in a consumer vision. If everyone knows what everyone else looks like, isolated comets can no longer exist, or are exploited. The true frontier today isn’t between what’s mainstream and what isn’t, but between what’s interesting and what’s crap. There are plenty of things I adore, but I also feel a form of cultural abyss.

What excites you today?

Moments, sounds, chance fragments that I stumble across. It doesn’t happen much in the movies anymore. What knocks me over usually comes from real life. I get more of a vibe from diving with an undersea rifle than watching a film. Of course I still like making movies. Whatever the film I make, my method is pretty much the same. With better-known actors, particular problems can arise, but at bottom it’s the same practice. I’ve never had a serious problem with actors, even the stars – they all know I’m going to wreak havoc!

Harmony Korine at the Centre Pompidou, Paris, 6 October–5 November 2017