20

20

Khalik Allah and the somptuous drug addicts of Harlem

Since the age of 14, this video artist and photographer, today a member of the prestigious photo agency Magnum, has been walking the streets of Harlem and Brooklyn with his camera, capturing the raw reality of New York’s most disadvantaged populations.

By Alexis Thibault.

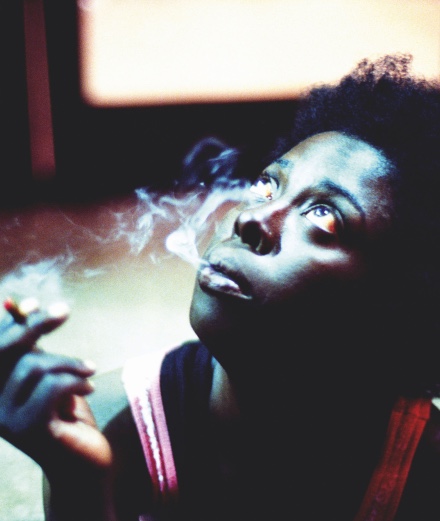

At night, Sapphire often wanders the streets of New York, especially the intersection of 125th and Lexington, a meth-dealing hotspot where ghostly silhouettes get high on K2, a synthetic drug 100 times more powerful than marijuana. The photograph’s framing doesn’t really allow us to say where this girl, whose age is impossible to guess, has stopped in the black of the night – the photographer later explains she was daydreaming just a few metres from a detox centre. In between her fingers smoulders a joint – Sapphire is an indefatigable smoker whom Khalik Allah has often photographed, to the point where today she trusts him entirely and lets him come close. In this portrait from 2013, her blood-shot eyes fix the sky, while a curl of smoke escapes from her fleshy lips. Her pose recalls James Baldwin’s when he was photographed in his home in Saint-Paul-de-Vence 30 years earlier. Underneath her Nina Simone-on-crack appearance, Sapphire seems to be savouring a brief moment of quiet in the chaos of this moribund neighbourhood. Who knows what she might be thinking about at this precise moment…

“At night, in the streets of Brooklyn, the greatest danger is your own fear.”

Allah does not like to talk about what lies behind his portraits – his photographs speak for themselves. If he’s willing to tell Sapphire’s story, it’s because this picture of her is his favourite. In New York there are thousands of photographers out in the streets every day, but very few bother even to glance at the models who pose for Allah – unknowns with wasted faces and scarlet eye-whites, vagabonds with nicotine-yellowed teeth, American citizens who, in the ordinary course of things, would be seen only by surveillance cameras and security guards… In 2015, Allah documented New York’s sweltering summer nights, fixing his lens on what he calls “field niggas,” an ex- pression whose origin can be found in a 1963 speech made by Malcolm X. “In Message to the Grass Roots,” explains the 35-year-old photographer, “Malcolm X talks about the different slavery regimes. In the 18th century there were both ‘house ne- groes’ and field labourers: the latter – the ‘field niggas’ – were more often tortured and killed than the former. Today, field niggas beg in the streets of New York, slaves to capitalist industry. No one gives a damn out the people I photograph.”

At night, Sapphire often wanders the streets of New York, especially the intersection of 125th and Lexington, a meth-dealing hotspot where ghostly silhouettes get high on K2, a synthetic drug 100 times more powerful than marijuana. The photograph’s framing doesn’t really allow us to say where this girl, whose age is impossible to guess, has stopped in the black of the night – the photographer later explains she was daydreaming just a few metres from a detox centre. In between her fingers smoulders a joint – Sapphire is an indefatigable smoker whom Khalik Allah has often photographed, to the point where today she trusts him entirely and lets him come close. In this portrait from 2013, her blood-shot eyes fix the sky, while a curl of smoke escapes from her fleshy lips. Her pose recalls James Baldwin’s when he was photographed in his home in Saint-Paul-de-Vence 30 years earlier. Underneath her Nina Simone-on-crack appearance, Sapphire seems to be savouring a brief moment of quiet in the chaos of this moribund neighbourhood. Who knows what she might be thinking about at this precise moment…

“At night, in the streets of Brooklyn, the greatest danger is your own fear.”

Allah does not like to talk about what lies behind his portraits – his photographs speak for themselves. If he’s willing to tell Sapphire’s story, it’s because this picture of her is his favourite. In New York there are thousands of photographers out in the streets every day, but very few bother even to glance at the models who pose for Allah – unknowns with wasted faces and scarlet eye-whites, vagabonds with nicotine-yellowed teeth, American citizens who, in the ordinary course of things, would be seen only by surveillance cameras and security guards… In 2015, Allah documented New York’s sweltering summer nights, fixing his lens on what he calls “field niggas,” an ex- pression whose origin can be found in a 1963 speech made by Malcolm X. “In Message to the Grass Roots,” explains the 35-year-old photographer, “Malcolm X talks about the different slavery regimes. In the 18th century there were both ‘house ne- groes’ and field labourers: the latter – the ‘field niggas’ – were more often tortured and killed than the former. Today, field niggas beg in the streets of New York, slaves to capitalist industry. No one gives a damn out the people I photograph.”

In his career to date, Allah has never considered himself a photo-journalist. Yet, in the bad streets of Brooklyn and Harlem, he behaves just like a reporter documenting drug addicts, people whom many city dwellers consider wild animals, seeing in them only their terrifying aspect. “I use my body as a zoom,” says Allah. “When I approach someone, I look for the humanity in them, that spark that slumbers inside and which they don’t even suspect is there. Because I want to take a photo ‘with’ them. In the end, when I’ve gained their assent, I capture their look. Aren’t the eyes the window to the soul?” Allah is always fully conscious of what he’s doing: even if he doesn’t carry a weapon and has never been attacked, he knows perfectly well that an invisible enemy is watching in the shadows. “At night, in the streets of Brooklyn, the greatest danger is your own fear.”

Born in 1985 to an Iranian father and a Jamaican mother, Allah is the third of five brothers. His parents were both originally from Bushwick, Brooklyn – a neighbourhood considered, until the late 90s, one of the most dangerous in New York – but left their childhood context of flour- ishing street art for the much more middle-class Flushing, Queens, where the resourceful Khalik grew up. Hating school, he cut his teeth in the streets of Harlem, the cradle of jazz, where he met Eglin Turner and Jason Hunter – better known by their aliases Masta Killa and Inspectah Deck –, two of the nine members of the Wu-Tang Clan, the legendary hip-hop group founded in 1992. With his trusty Camescope, the 14-year- old Allah followed the bemused rappers in all their New York wanderings, shooting them in every corner of the Big Apple. It was also at this time that he discovered the Five-Percent Nation, an African-American organization founded in 1964 by a Korean War veteran named Clarence 13X. Initiated into this branch of the Nation of Islam, Allah learned about his identity as a mixed-race child and was soon swearing only by the Twelve Jewels of Islam, precepts intended to help understand the universe, which include liberty, justice, equality, knowledge and peace. It wasn’t until 2010 that Allah shot his first movie, Popa WU: A 5% Story, an old-school voyage into the psyche of music producer Popa Wu, mentor to the Wu-Tang Clan.

In his career to date, Allah has never considered himself a photo-journalist. Yet, in the bad streets of Brooklyn and Harlem, he behaves just like a reporter documenting drug addicts, people whom many city dwellers consider wild animals, seeing in them only their terrifying aspect. “I use my body as a zoom,” says Allah. “When I approach someone, I look for the humanity in them, that spark that slumbers inside and which they don’t even suspect is there. Because I want to take a photo ‘with’ them. In the end, when I’ve gained their assent, I capture their look. Aren’t the eyes the window to the soul?” Allah is always fully conscious of what he’s doing: even if he doesn’t carry a weapon and has never been attacked, he knows perfectly well that an invisible enemy is watching in the shadows. “At night, in the streets of Brooklyn, the greatest danger is your own fear.”

Born in 1985 to an Iranian father and a Jamaican mother, Allah is the third of five brothers. His parents were both originally from Bushwick, Brooklyn – a neighbourhood considered, until the late 90s, one of the most dangerous in New York – but left their childhood context of flour- ishing street art for the much more middle-class Flushing, Queens, where the resourceful Khalik grew up. Hating school, he cut his teeth in the streets of Harlem, the cradle of jazz, where he met Eglin Turner and Jason Hunter – better known by their aliases Masta Killa and Inspectah Deck –, two of the nine members of the Wu-Tang Clan, the legendary hip-hop group founded in 1992. With his trusty Camescope, the 14-year- old Allah followed the bemused rappers in all their New York wanderings, shooting them in every corner of the Big Apple. It was also at this time that he discovered the Five-Percent Nation, an African-American organization founded in 1964 by a Korean War veteran named Clarence 13X. Initiated into this branch of the Nation of Islam, Allah learned about his identity as a mixed-race child and was soon swearing only by the Twelve Jewels of Islam, precepts intended to help understand the universe, which include liberty, justice, equality, knowledge and peace. It wasn’t until 2010 that Allah shot his first movie, Popa WU: A 5% Story, an old-school voyage into the psyche of music producer Popa Wu, mentor to the Wu-Tang Clan.

Allah remembers his first camera very well: it was a Canon AE-1, a heavy, entirely manual machine made of metal, which his father, who only ever took it out of its case once or twice a year at Christmas and Thanksgiving, agreed to lend him (something he hadn’t done for his elder brother). It goes without saying that the young Allah immediately became passionate about photography, the ideal complement to his video work. “If I’d had a better camera, I would have never gotten where I am today. I had to develop the images myself, and learn from my mistakes. I could, like many others, have been content simply to photograph stars or to produce pretty pictures for magazines. But to say what? Instead, I let myself be swallowed up by the city so as to immortalize the people who have to affront the street. For the space of an instant, I infiltrate their lives. It’s then that my work takes on all its meaning.”

Allah, who has always remained close to the world of hip-hop, considers his photographs to be “visual words.” Nobody, not even a photographer, pushed him to take up the profession, but there are of course past masters who have influenced his way of seeing the world: Robert Frank, William Klein, Jamel Shabazz and Daido Moriyama, for whom photography is akin to a hunt. In the work of Nobuyoshi Araki, it’s the intrepid side that appeals; as for Henri Cartier-Bresson, Allah remembers a book, The Decisive Moment (1952), which taught him almost everything. “You must constantly remain alert and always consider the subject of the image,” he recites, like a credo. “When you press the shutter release, it’s imperative that you’re physically involved.”

After recently joining the prestigious Magnum agency, Allah is currently on a two-year trial period under the guidance of an established member of the collective. If he passes muster, he will become an official associate photographer, employed full time by the cooperative, although not yet a full member. Whatever happens, Allah has no intention of changing course or of “shooting with a Leica,” as most of his confrères do. And it would take even more for him to abandon Rondoo, Frenchie, Sapphire and all the other temporary residents of the streets of Harlem, these sumptuous fragile monsters who haunt the corner of 125th and Lexington.

Allah remembers his first camera very well: it was a Canon AE-1, a heavy, entirely manual machine made of metal, which his father, who only ever took it out of its case once or twice a year at Christmas and Thanksgiving, agreed to lend him (something he hadn’t done for his elder brother). It goes without saying that the young Allah immediately became passionate about photography, the ideal complement to his video work. “If I’d had a better camera, I would have never gotten where I am today. I had to develop the images myself, and learn from my mistakes. I could, like many others, have been content simply to photograph stars or to produce pretty pictures for magazines. But to say what? Instead, I let myself be swallowed up by the city so as to immortalize the people who have to affront the street. For the space of an instant, I infiltrate their lives. It’s then that my work takes on all its meaning.”

Allah, who has always remained close to the world of hip-hop, considers his photographs to be “visual words.” Nobody, not even a photographer, pushed him to take up the profession, but there are of course past masters who have influenced his way of seeing the world: Robert Frank, William Klein, Jamel Shabazz and Daido Moriyama, for whom photography is akin to a hunt. In the work of Nobuyoshi Araki, it’s the intrepid side that appeals; as for Henri Cartier-Bresson, Allah remembers a book, The Decisive Moment (1952), which taught him almost everything. “You must constantly remain alert and always consider the subject of the image,” he recites, like a credo. “When you press the shutter release, it’s imperative that you’re physically involved.”

After recently joining the prestigious Magnum agency, Allah is currently on a two-year trial period under the guidance of an established member of the collective. If he passes muster, he will become an official associate photographer, employed full time by the cooperative, although not yet a full member. Whatever happens, Allah has no intention of changing course or of “shooting with a Leica,” as most of his confrères do. And it would take even more for him to abandon Rondoo, Frenchie, Sapphire and all the other temporary residents of the streets of Harlem, these sumptuous fragile monsters who haunt the corner of 125th and Lexington.