20

20

From a joke to full-on terrorism, the grotesque beginnings of the Ku Klux Klan

With the release of David Korn-Brzoza ‘s documentary that retraces the little-known history of the Ku Klux Klan on the Franco-German TV station Arte, we look back at the violent and grotesque beginnings of the white supremacist group, whose racist demons still haunt the USA.

By Lucas Aubry.

In 1865, the American Civil War ended with a victory for the Northern troops, paving the way for the abolition of slavery. On December 18th, the 13th amendment to the Constitution of the United States comes into force and frees, by law, the four million black American slaves from servitude. But in the southern states, traumatised by the defeat and largely opposed to these new laws, many citizens try to perpetuate white supremacism by any means.

In the small town of Pulaski in the heart of Tennessee, a handful of veterans founded a secret society where together they evoke memories of past battles and the good old days of the pro-slavery South. Proud of having studied ancient languages at university, they call it the Ku Klux Klan in reference to the term “Kuklos”, which means “the circle” in Greek. “It was just a bunch of guys looking for an excuse to get together, have a beer and help each other out,” explains a former Klan member in the documentary Ku Klux Klan, an American History (2019) by David Korn-Brzoza.

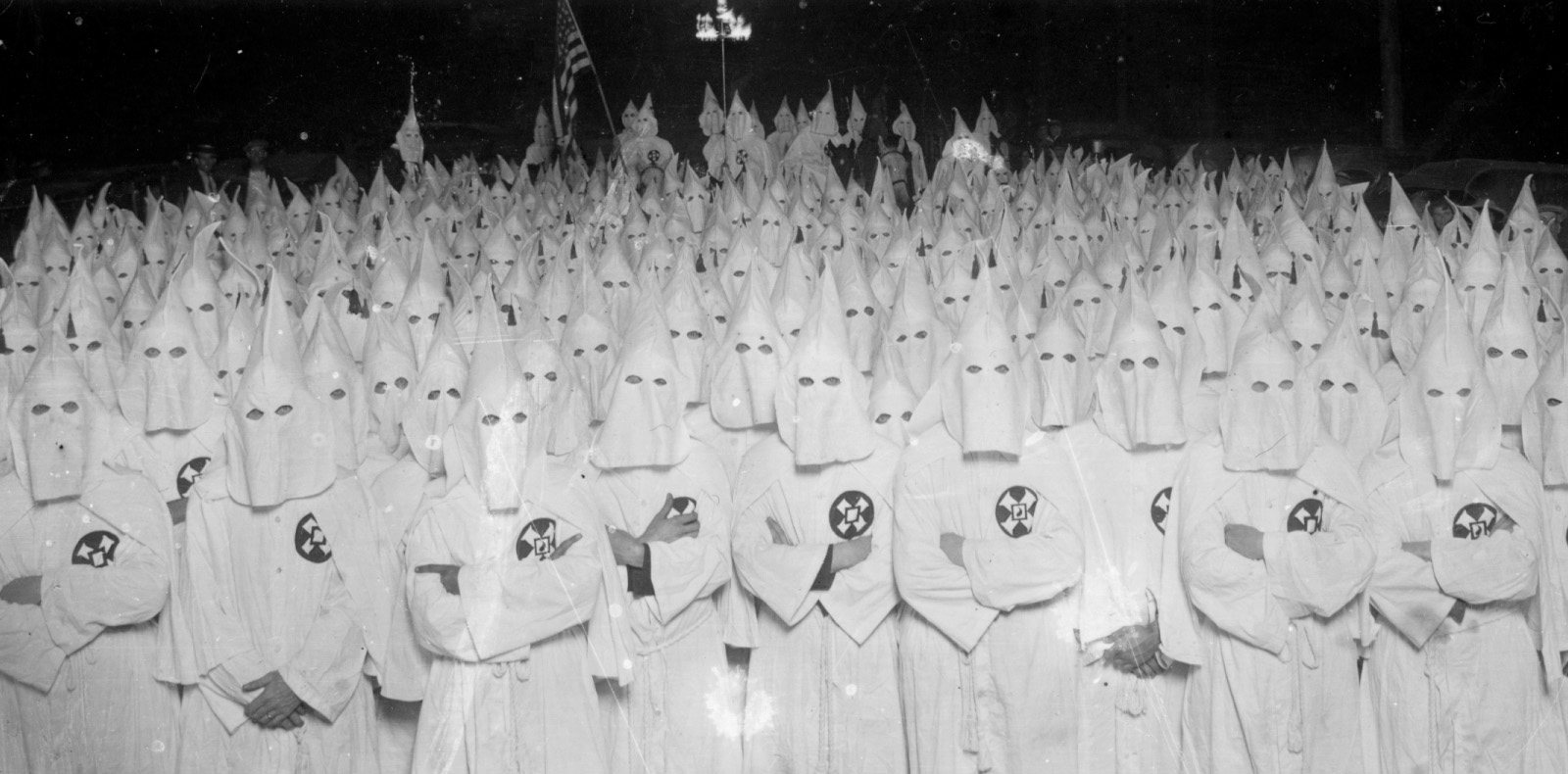

The story of the Ku Klux Klan began as a bad joke. Young Americans with a passion for mythology imagining themselves as a brotherhood of modern-day knights, the pious defenders of the foul memory of slavery. During night rides, they disguised themselves as all sorts of monsters – the white sheet suit came later – to terrorise the African-American population, who they knew to be particularly superstitious. Drunkenly they uttered animal cries, adopted brazenly low voices or would sing with a German accent. In many ways, the original members were as ridiculous as those depicted in the Coen brothers’ comedy O Brother Where Art Thou? (2000), where George Clooney and his band of escaped ex-convicts get caught up in a Klan ceremony that looks more like a Broadway musical performed by a bunch of cack-handed loonies than a meeting of terrorists.

In 1865, the American Civil War ended with a victory for the Northern troops, paving the way for the abolition of slavery. On December 18th, the 13th amendment to the Constitution of the United States comes into force and frees, by law, the four million black American slaves from servitude. But in the southern states, traumatised by the defeat and largely opposed to these new laws, many citizens try to perpetuate white supremacism by any means.

In the small town of Pulaski in the heart of Tennessee, a handful of veterans founded a secret society where together they evoke memories of past battles and the good old days of the pro-slavery South. Proud of having studied ancient languages at university, they call it the Ku Klux Klan in reference to the term “Kuklos”, which means “the circle” in Greek. “It was just a bunch of guys looking for an excuse to get together, have a beer and help each other out,” explains a former Klan member in the documentary Ku Klux Klan, an American History (2019) by David Korn-Brzoza.

The story of the Ku Klux Klan began as a bad joke. Young Americans with a passion for mythology imagining themselves as a brotherhood of modern-day knights, the pious defenders of the foul memory of slavery. During night rides, they disguised themselves as all sorts of monsters – the white sheet suit came later – to terrorise the African-American population, who they knew to be particularly superstitious. Drunkenly they uttered animal cries, adopted brazenly low voices or would sing with a German accent. In many ways, the original members were as ridiculous as those depicted in the Coen brothers’ comedy O Brother Where Art Thou? (2000), where George Clooney and his band of escaped ex-convicts get caught up in a Klan ceremony that looks more like a Broadway musical performed by a bunch of cack-handed loonies than a meeting of terrorists.

But make no mistake about it, as grotesque as it may seem, the Ku Klux Klan, right from the off, was home to a wave of racist violence that would soon come to the fore. As the 1868 American elections approached, attacks on the black population multiplied. The Ku Klux Klan organised itself into a multitude of paramilitary organisations, blocking the entrances to polling stations and savagely murdering opponents in an attempt to dissuade the rest of the African-American population from voting. In just four weeks, these white supremacist militia committed more than a thousand murders in the southern United States, going so far as to burn down sheriff’s offices and courts that got in their way.

When the government in Washington first disbanded the Ku Klux Klan four years later, many of its members and allies were at the head of a vast number of institutions and had little need to carry out attacks. Under the Jim Crow laws, which restricted black people’s access to schools, public transport, restaurants, concert halls and even toilets, ruthless segregation succeeded slavery in the southern states. This lasted for nearly a century.

The Ku Klux Klan reformed in 1915, brought up to date by the huge success of David W. Griffith’s film Birth of a Nation in an America where millions of Europeans were beginning to flock. The hatred now extended to immigrants, Jews, Catholics, Communists and continues today to inspire white supremacists who, reinvigorated by the election of Donald Trump in 2016, still haunt the USA.

“Ku Klux Klan, an American History” (2019) by David Korn-Brzoza, is available on Arte.

But make no mistake about it, as grotesque as it may seem, the Ku Klux Klan, right from the off, was home to a wave of racist violence that would soon come to the fore. As the 1868 American elections approached, attacks on the black population multiplied. The Ku Klux Klan organised itself into a multitude of paramilitary organisations, blocking the entrances to polling stations and savagely murdering opponents in an attempt to dissuade the rest of the African-American population from voting. In just four weeks, these white supremacist militia committed more than a thousand murders in the southern United States, going so far as to burn down sheriff’s offices and courts that got in their way.

When the government in Washington first disbanded the Ku Klux Klan four years later, many of its members and allies were at the head of a vast number of institutions and had little need to carry out attacks. Under the Jim Crow laws, which restricted black people’s access to schools, public transport, restaurants, concert halls and even toilets, ruthless segregation succeeded slavery in the southern states. This lasted for nearly a century.

The Ku Klux Klan reformed in 1915, brought up to date by the huge success of David W. Griffith’s film Birth of a Nation in an America where millions of Europeans were beginning to flock. The hatred now extended to immigrants, Jews, Catholics, Communists and continues today to inspire white supremacists who, reinvigorated by the election of Donald Trump in 2016, still haunt the USA.

“Ku Klux Klan, an American History” (2019) by David Korn-Brzoza, is available on Arte.