10

10

Tribute to photographer Sabine Weiss in 5 iconic shots

In 2016, the Jeu de Paume gallery in Paris dedicated a retrospective to her. Last summer, she was part of the photography festival Rencontres de la Photographie in Arles. On December 28th, 2021, Sabine Weiss passed away at the age of 97. Along with Robert Doisneau and Henri Cartier-Bresson, the Swiss artist was up to now the last representative of humanist photography, a movement which focused on the study of human beings in their daily lives. Over her gigantic career, she used to describe herself as a “mere witness” and would produce photo-reports for numerous newspapers, make portraits of the greatest artists of her time or immortalize famous designers’ fashion shows, whilst often showing through her lens “anonymous” people from her society, like beggars and gypsies.

By Chloé Bergeret.

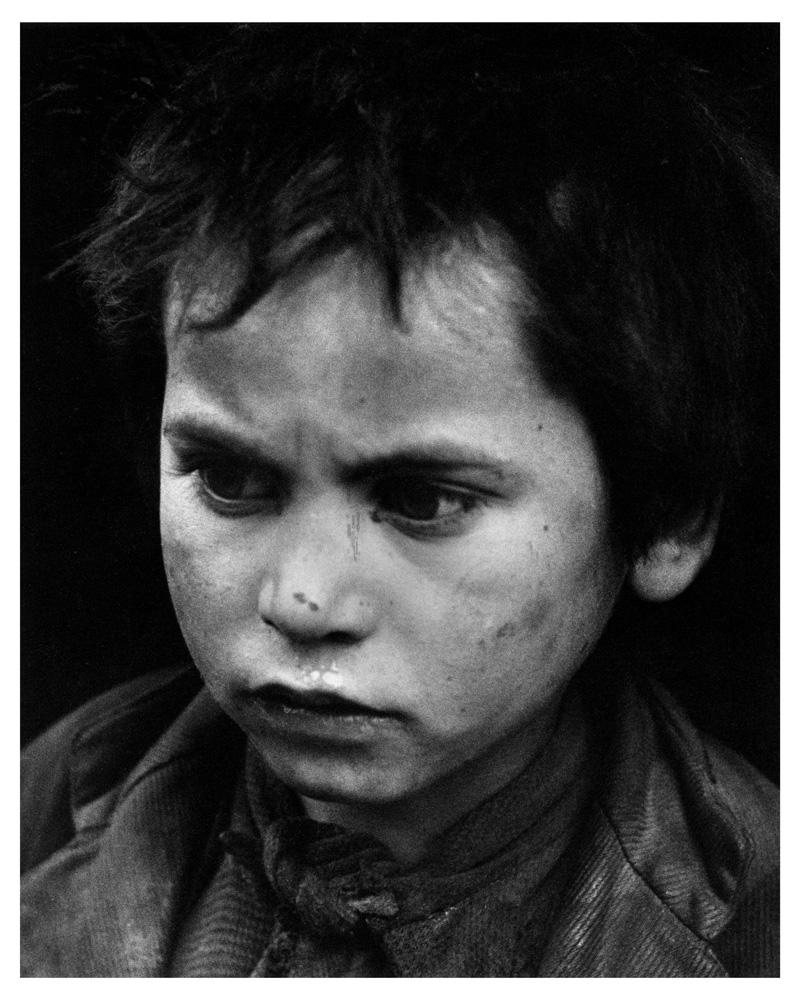

1. Childhood: the sincerity of emotions.

Sabine Weiss is not solely a celebrities’ photographer. From her debuts, the Swiss photographer developed an interest in childhood and its facetiae. Her whole life, she had been fascinated by the games of the youngest, their attitudes and expressions, whether they were rich or poor, cheerful, in tears or joyful, and she had been wandering around the streets in search of these “little snots” she loved so much. Taken in 1950, her photograph of a young beggar in Toledo streets remains one of her prominent shots today. The boy’s dirty face, frowned eyebrows and mature look move us, and even though he looks away, his eyes are remembered. In her book Intimes Convictions (ed. Contrejour, 1989), Sabine Weiss explains that she enjoys taking pictures of children because “their masks fall more easily” and that she “understands their reality”. To her the “average anonymous executive with a striped shirt and a tie has learned to better hide himself”. Perhaps it is among these topics that the photographer pushes her humanistic approach farther: far from an excessive pity or a mere entertainment, she finds the right balance through empathy and testimony of the real.

2. Shooting fashion with humor

In 1952, Sabine Weiss started a ten-year- long collaboration with Vogue magazine. It was the beginning of an extended period of collaboration between the photographer and several prestigious women’s publications. The discrepancy between her personal work and her editorial orders is intense, although her style is still present. In this 1955 photograph, two models sitting down on a bench mirror themselves with a witty look. The dotted dresses cut sharp from the gloomy background of the naked trees. In her work as a fashion photographer, Sabine Weiss stages and designs her sceneries by herself, thus keeping her originality in contrast to other photographers: a light and often comic tone.

3. Photographer for the greatest artists of her time

In 1950, Sabine (born Weber) married the American painter Hubert Weiss and became an independent photographer. Eight years later, she joined the Rapho agency, next to Robert Doisneau and Willy Ronis, and shared her time between orders and personal series. Established within the Parisian artistic sphere thanks to her work and her relatives, she spent time with many artists and intellectuals, who also posed for her. Her closeness with these musicians, painters, and writers, creates intimate portraits in which the young woman captures their inner selves. Here, she took a portrait of Niki de Saint Phalle, right in the middle of her creative work: the artist appears focused on her canvas, hunched, and covered in paint. She doesn’t look at the lens and remains absorbed in her art making, while Sabine Weiss watches her as a silent spectator of her creative moment. The representation of the artist at work is precious to the photographer, as when she immortalized the famous sculptor Alberto Giacometti in his studio.

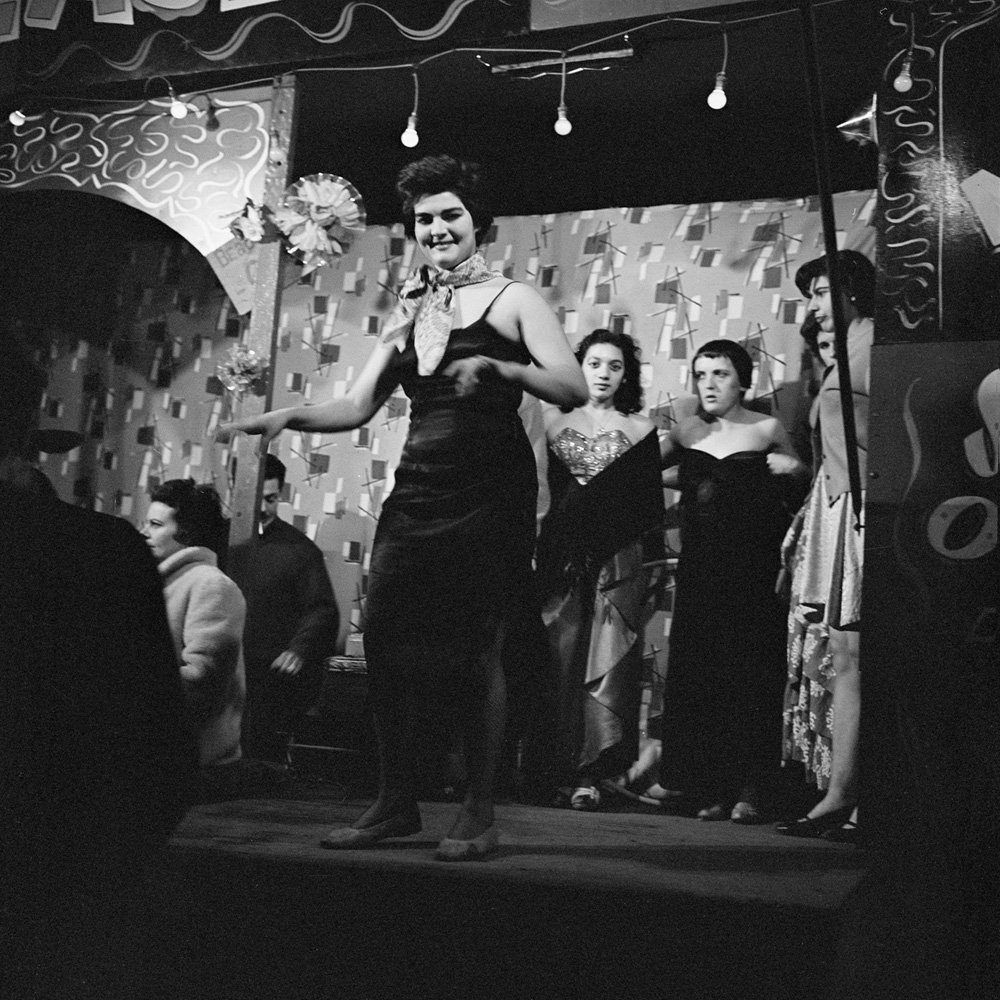

4. Parisian nights: embodiment of a lust for life.

Laughing faces and confetti are recurring motives in Sabine Weiss’s pictures. For decades, she walked through Parisian streets and European cities to shoot parties and night owls. Her post-war shots bear witness of a general elation and zest for life, despite the efforts made to rebuild a considerably weakened and ruined Europe. Here, she succeeds in translating the euphoria that animates these young transvestites, while performing on stage some night in Pigalle, into a festive and colorful spirit, despite her relentless black and white. In her book Intimes Convictions, she declares choosing this technique for its “simplicity and a more straightforward contact” with her subjects. “Technical issues are minimized, she writes. The mind is free to go deeper, to transcend the anecdotal, to move towards a bare abstraction… As I am more and more searching for a form of simplicity, of silence, of tranquility, I think that black and white can more easily express that feeling”.

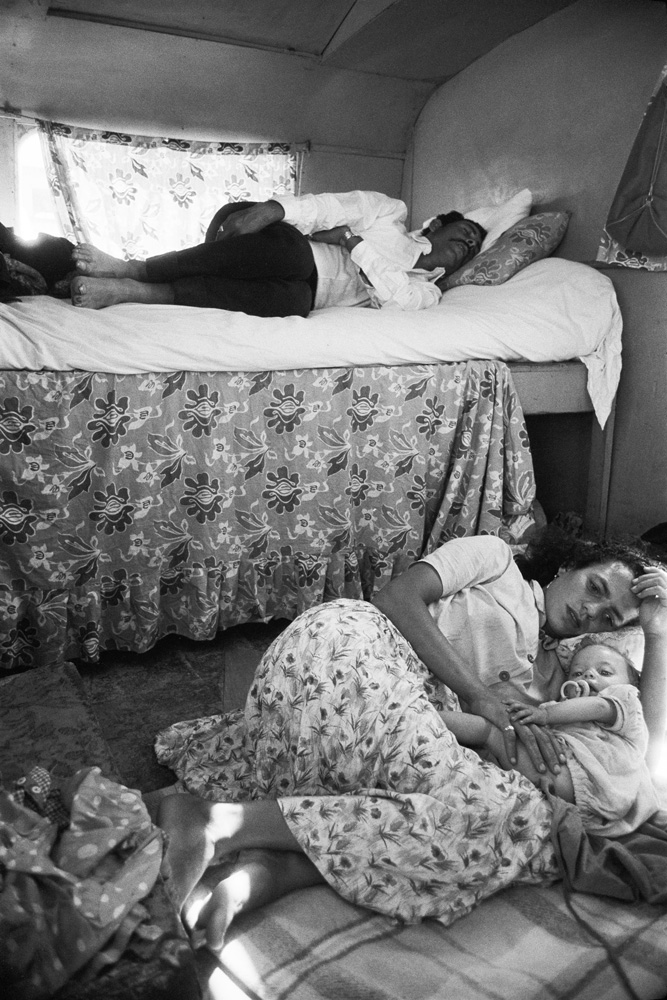

5. Gypsies, or the unbounded solidarity

Sabine Weiss was well-known for her work on gypsy communities, especially in the French coastal town of Saintes- Marie-de-la-Mer, an important pilgrimage site, or in Geneva streets where she grew up. Driven by her kindliness and curiosity, she formed trustworthy relationships with these nomadic populations and could capture them in their private life – at weddings and during other ceremonies for instance. To create this photograph, an entire gypsy family agreed to open their caravan’s doors for her. Crammed on top of each other on small bunk beds, the family members alone symbolize realities specific to gypsy communities: a precarious lifestyle, but also a strong sense of family and a certain aesthetic, highlighted here by the motley fabrics. Sabine Weiss likes shooting humble people as witnesses of their own existence and, above all, humanity. In a 2003 monograph, she developed her conception of her own approach: “I take photographs to preserve the ephemeral, to contain fate, to keep what is about to disappear in a picture: movements, attitudes, objects that are witnesses of our time on earth. The camera collects and fixes them, while they disappear at the same time”. It is an act all the more essential which marks the faces of our society’s invisibles and anonymous, who yet make all its richness, forever on the roll.