13

13

Photographer Thomas Demand blurs the lines between reality and fiction in a fake news era

Numéro art talks to the legendary German photographer on the occasion of his solo show, Mundo de Paper, at the Centro Botin in Santander, Spain.

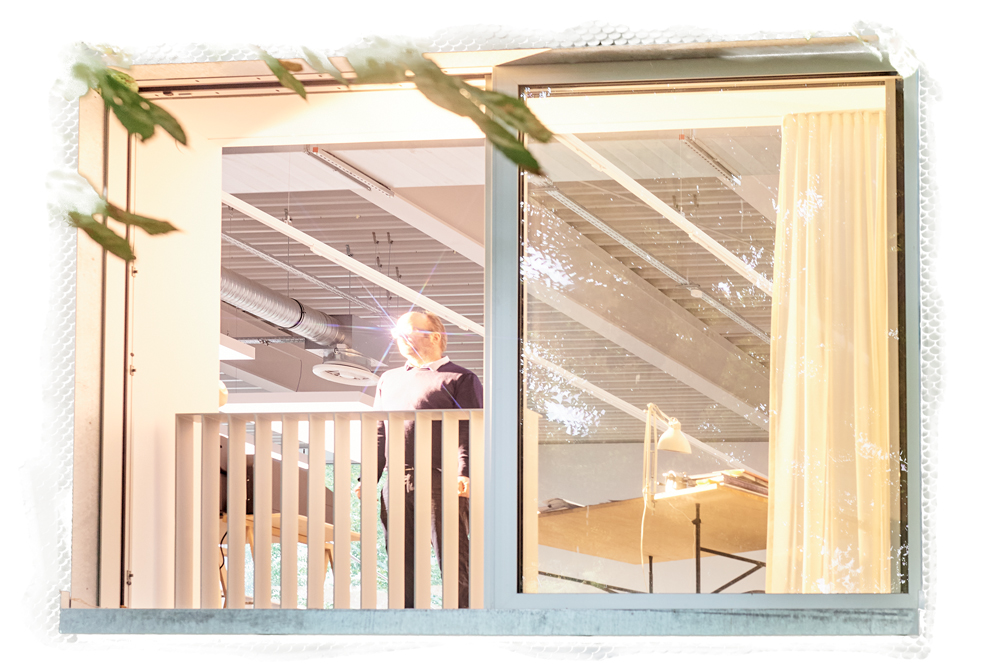

Portraits by Karl Felix,

Interview by Heinz-Peter Schwerfel.

Numéro art : Your photographs often feature a life-size reconstruction of a crime scene, regardless of whether it’s really a crime or a political event… These photos are also often inspired by images found in the press or archives, or come from police sources. Your art re- volves around the relationship between truth and truthfulness, between reliable information and falsified information. But the artwork that results from your methodology is itself an “artefact.” Why should we trust the intentions of an artist and a work of art more than an anonymous source of information?

Thomas Demand : Firstly, it’s difficult these days to know whether the original source of information, anonymous or not, is real, simply because images can now be manipulated in such a way that no one is aware of the manipulation. Secondly, I’m not interested in factual truth, I’m more interested in truthfulness in a literary sense. If a writer like Vladimir Nabokov talks about his childhood in St. Petersburg, you might be able to prove that his uncle’s name was Boris not Igor, but that won’t change the literary quality of his book. I hope the same goes for me – I don’t work with facts but with the telling of those facts, with the ability to com- municate and with the proliferation of images in a societal context. For my art, I don’t need factual truth, my subject is the fictional capacity of an image to tell us something.

You mention a very important concept: fiction. What significance does fiction have in your art?

For the last ten years or so, we have been forced to get used to the notion of the fake, to the deliberate claims of a manipulated reality or truth. The same goes for photogra- phy: its truth content is very diminished, yet we’ve learnt to live with it. Our iconography is probably different from that of 50 or 70 years ago, but we deal with it quite well. That’s what interests me as an artist. We have this ability to analyse the authenticity of each image and to verify its source.

How do you choose your subjects, and according to what criteria? You mentioned the societal importance, but are there also more personal connections – to your own biography for example? There are, but as an individual I’m not very interesting. So I have to find a way to eliminate everything that is autobiographical. For example, I have a photo of myself as a child, taken in my room, among my toys. What interests me in this photo is the toy as a model, our relationship with toys, their cultural significance at that time. That’s why I built a model of my childhood bedroom, which I then photo- graphed. And then there are the Dailies, everyday impres- sions that I photograph while walking down the street, like a passerby. They’re a kind of visual haiku that you can walk through. I’m showing some of them in Santander.

What is the difference between your models and the media images you use? What do you eliminate?

I try to eliminate the anecdotal from the image. Anything that I consider anecdotal, I remove. I strive to create a specific moment in which a person could potentially arrive at a place, or in which another person has just left. I’m not interested in idealizing the look of the place, but I want to put it into a certain temporality.

The disappearance of the human being plays a large part in your “purification” of the model: the human being exists only as a trace, a possibility. The most important protagonist is the architecture of the place.

If a place is interesting, if it has a certain atmosphere, then it can tell its own story. But sometimes, thanks to a remarkable event, quite trivial places suddenly acquire an aura. Unexpectedly they are no longer trivial at all, or become even more trivial, but that can be interesting too. And yet the objects in the place always remain the same, and that’s precisely what interests me. At what point does a space acquire its aura, when does it start to tell its story? There is no one in my pictures, that’s true, but there is nevertheless a human presence, which is mine. Because everything you see is made with my own hands. And there’s another factor that shouldn’t be underestimated: that a space is empty, that no one occupies it, makes it easier to project yourself into that space. Because if other human beings were present, it would inevitably add a narrative to the image.

What role do the dimensions of your models and the format of your photographs play?

I live with the 1:1 scale. The building opposite me is 1:1, as are all the objects around me. Why increase or decrease them? To reduce them would perhaps make them cuter, but I want to avoid this cutesy aspect. My models are sculptures, and as sculptures they have a certain presence in space. Thanks to the 1:1 scale, I can draw on my daily life and experiences. I can make them credible. As far as the photos are concerned, they function as windows, which is why I need the large format.

Your titles are at once precise and minimalist, and yet always slightly vague.

It depends. Because I’m trying to get in touch with the memory of an image or a place discovered in the media, I try to find simple titles, but without them being totally vague. For example, I don’t want to give up the title by writing Untitled. The title must be related to the place and the subject without limiting the interpretation.

The Centro Botín has allowed you to create a very spe- cial layout for your exhibition, a sort of “urban land- scape.” Can you talk about this?

The aim is to create an exhibition for the local public, i.e. people who are not necessarily so familiar with art. The Mundo de Papel exhibition is made up of about 30 photographs, plus eight pavilions. These pavilions, which hang from the ceiling and float about 30 cm above the floor, can be accessed by the public. Renzo Piano’s Centro Botín stands on pilotis that you can walk around. Statically it’s very daring: it’s located by the sea and is partly built over the ocean, so it was necessary to balance it from an engi- neering point of view, resulting in a massive, heavy steel ceiling that is visually very dominant in the exhibition space. That’s why this ceiling is usually hidden behind some kind of cladding, but I find it very original, so I decided to hang my whole exhibition from it.

So the room is just one single space?

Exactly, but the public can enter the eight pavilions sus- pended from the ceiling. There’s one that I call “Trump Tower,” which contains two works about Donald Trump. Then there’s a perfectly round pavilion that serves as a cinema for my films. Another is shaped like a labyrinth, another is reminiscent of 19th-century museums with stucoed ceilings, and so on. The two long perimeter walls are lined with a kind of forest made of pipes, and the inside of the pavilions is also lined with various images, as well as instructions in folded paper.

Why this staging of works that already deal with the subject of staging?

Most museums have their own characteristics. Some have a single, large exhibition space. This puts limits on artists and makes it difficult for them to show their work. For me, an exhibition is much more than the sum of the pieces presented.

For the public, this means that diving into a particular world, typical of your art, gains another dimension thanks to the staging of the exhibition.

Yes, the theatrical effect is both reinforced and adjusted, because normally the two-dimensional photograph replaces a three-dimensional model made in the studio. In the exhibition space, the three-dimensional effect becomes even stronger, without using the same means. And I have to admit that this extra dimension of the exhibition features amuses me, it makes me happy.

Collaborating with other artists, curators or architects seems to be very important to you, the most famous example being the exhibition The Boat is Leaking. The Captain Lied. in 2017 at the Prada Foundation in Venice. Why this desire to collaborate?

My works are born in my studio, where I’m alone, working with my hands and not on a screen. Creation is done in solitude, but when it’s finished a new chapter begins, the exhibition, and for that I need help. This is all the more necessary when you don’t produce much and you don’t want to exhibit the same work all the time. For exhibitions, you have to try to find constellations that allow a different reading of the works, different even from their author’s initial intentions. And here we need others, people like the film- maker and intellectual Alexander Kluge, or the curator Udo Kittelmann. Sometimes it’s difficult to know the result in advance, but if everything goes well a dialogue is born, like a game of ping-pong. Where architects are concerned, they were interested in my work very early on, and I’ve always been interested in architecture too.

Thomas Demand, Mundo de Papel, Centre Botín, Santander. Until 6th march of 2022.