4

4

What is to know about Chantal Akerman’s exhibition at the Jeu de Paume?

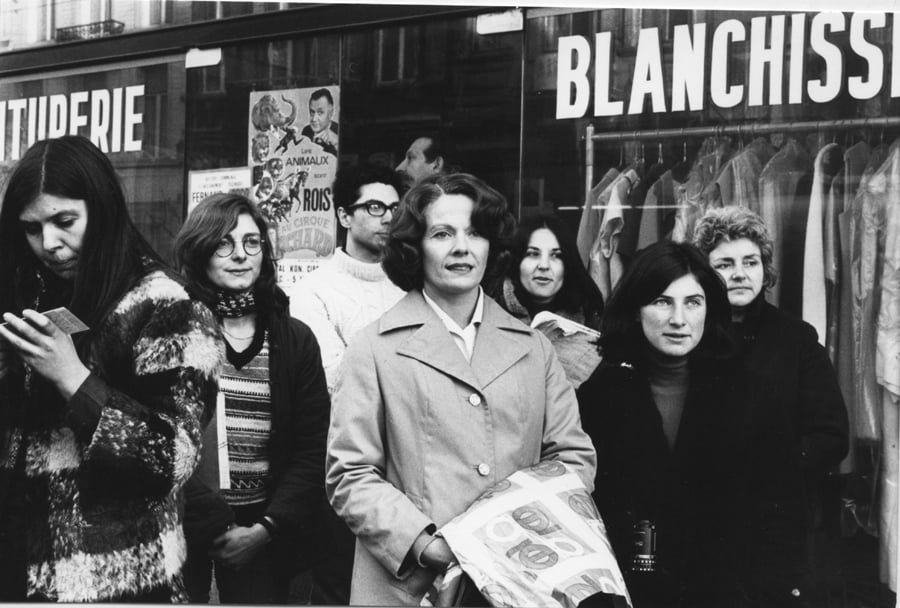

This autumn, to celebrate its 20th birthday, Paris’s Jeu de Paume is honouring the late Belgian filmmaker Chantal Akerman with a much-anticipated retrospective. As well as movies and video installations, the programme will include readings, performances, and events.

Interview by Delphine Roche.

Published on 4 October 2024. Updated on 7 November 2024.

Chantal Akerman: a long-awaited retrospective at the Jeu de Paume

In 2022, to general surprise, Jeanne Dielman, 23, quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles (1975) was voted the greatest movie of all time in the ten-yearly critics poll conducted by the British film magazine Sight and Sound. This unexpected result says a lot about the reevaluation of director Chantal Akerman‘s oeuvre since her death in 2015.

As Paris’s Jeu de Paume gears up for Travelling, a huge exhibition dedicated to the Belgian filmmaker (coproduced with Brussels’s Palais des Beaux-Arts, the Chantal Akerman Foundation, and Belgium’s Cinémathèque royale), Numéro spoke to the show’s curator, Marta Pensa.

Interview with Marta Ponsa, curator of the exhibition

Numéro : Would you say that Chantal Akerman’s oeuvre is undergoing a renaissance?

Marta Ponsa: Over the course of my career, I’ve never seen such effervescence around her work. A whole new generation of scholars is now interested in her, whereas I think she felt rather forgotten at the end of her life. Since the exhibition was announced, we’ve received countless e-mails from filmmakers, writers, and PhD students all over the world.

People say things like, “I’ve filmed the Hotel Monterey in New York, which she made a movie about in 1972.” Thanks to the Chantal Akerman Foundation, we’re going to show a lot of working documents in the exhibition, and we’re also organzing a series of thematic events around her movies. We’ll be including Chantal’s scripts, which show all the beauty and poetry of her writing – literature was a big inspiration for her, and she always said she would have become a writer if cinema hadn’t got there first. But we’ll also be showing account books, subsidy requests, and all sorts of other administrative documents that give an idea of the economic conditions under which she worked.

In 1995, in parallel to her big-screen productions, Akerman began developing multi-screen installations which she showed at prestigious art events such as Documenta and the Venice Biennale. How important was this aspect of her work?

Her very first installation, D’Est, au bord de la fiction, premièred at the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis, which had invited her to try her hand at this kind of piece. Straight away afterwards it travelled to the Jeu de Paume. In the years that followed, Akerman would continue experimenting with installations, which allowed her to make time and duration felt in totally different ways. We’ll be showing a selection of them, such as A Voice in the Desert, in which you hear Chantal trying to reconstruct, in French, Spanish, and English, the story of a deceased Mexican woman who worked in the US.

Her voice recounts the memories of those who knew her, while on screen we see night-time images shot on a freeway linking Mexico to the US, with heavy traffic moving at a slow pace. It’s a very touching piece, and I felt it was essential for the show. Given the way they occupy space and time, her installations – particularly this one – establish a strong connection with Chantal’s sensibility, chiming with her political engagement towards the oppressed and towards those who are forced to migrate.

“In one installation you have a young woman in the process of building her identity, worrying about the norms she’s supposed to measure up to, both literally and figuratively; in the other you have a woman who’s just revealed the stuff of which she’s really made.”

Marta Ponsa

Would you say there’s a link here with some of her films, for example her 1968 short Saute ma ville or Jeanne Dielman, where we see women who are shut away inside domestic space? Is it fair to say that her whole oeuvre is marked by the consciousness of unseen bodies at work?

Totally. To accompany the exhibition, we’ve produced a book, in collaboration with the Palais des Beaux-Arts in Brussels. It’s an anthology of texts, some written by those who worked with Akerman – like the director of photography Luc Benhamou or the film editor Claire Atherton – and others by directors who were inspired by her movies, such as Wang Bing and Christophe Honoré. I felt it was essential to include an essay by a Latin American author, since Chantal looked at the question of the US-Mexican border, and her sister currently lives in Mexico City. In her text, the Argentine sociologist Verónica Gago talks about women’s invisible work and the way that the “escape from domesticity,” the conquest of public space, was a major feminist battle, particular in her country, where, in 1977, the Madres de Plaza de Mayo demonstrated under the military dictatorship against their domestic confinement.

In the show, we establish a parallel between two installations that talk about women’s status and bodies. On the one hand there’s Woman Sitting After Killing, which is based on the final part of Jeanne Dielman, in which the heroine, after stabbing her client, remains seated; the only detail that gives away the violence that has interrupted her quiet daily routine is a bloodstain on her blouse. On the other hand, there’s In the Mirror, which shows the actor Claire Wauthion inspecting and measuring her body, in the manner of 1970s female artists like Orlan or Valie Export. In one installation you have a young woman in the process of building her identity, worrying about the norms she’s supposed to measure up to, both literally and figuratively; in the other you have a woman who’s just revealed the stuff of which she’s really made.

Why, in these installations, did Akerman seek to free herself from linear narrative?

The experience of time in these installations is almost physical. The relationship with the body, with the voice, is very present in her films, since you often hear her reading the voiceover. When Chantal was living in New York in the 1970s, Babette Mangolte, who would become her director of photography, introduced her to experimental filmmakers like Michael Snow. She regularly went to the Anthology Film Archives, where she discovered the possibility of a non-narrative cinema emancipated from established formats. And in a certain way this quest is clearly present in her writing, which is sensitive, fluid, bodily, and organic. You can see it in the autobiographical Ma mère rit, written in 2013, in which, in the same paragraph and without indicating the transition, she uses both her mother’s and her own voice. It’s written in a single breath, almost without punctuation.

In addition to showing her films, her archives, and her installations, you’ve organized a whole programme of events around her work.

Yes. While the exhibition is showing, many of those who worked with Akerman, but also filmmakers and artists from other disciplines who were influenced by her, such as the directors Eric Baudelaire and Céline Sciamma, or the choreographer Gisèle Vienne, will come to give introductions to her films in the movie theatre at the Jeu de Paume. There will be also be readings of some of her texts by Aurore Clément, an actor who was very close to her. Another actor, Anne Kessler of the Comédie-Française, will stage her 1992 monologue Le Déménagement in one of the galleries with the actor Stanislas Merhar.

And the film producer and publisher Capricci, in partnership with the Chantal Akerman Foundation, is bringing out a Blu-ray box set of almost her entire filmography, in restored versions, and is planning a retrospective of her work in commercial movie theatres – they’re starting with her earliest films, while we’ll begin with her most recent. To cap it all off, L’Arachnéen is publishing all of Chantal’s writings in three volumes-scripts, whether filmed or not, stories, plays, interviews, letters, etc. All of this material will allow for a deep rereading of her work, whose radical poetry still has a major influence on the young generations of today.

“Chantal Akerman – Travelling”, exhibition until January 19, 2025 at the Jeu de Paume, Paris 1st.