9

9

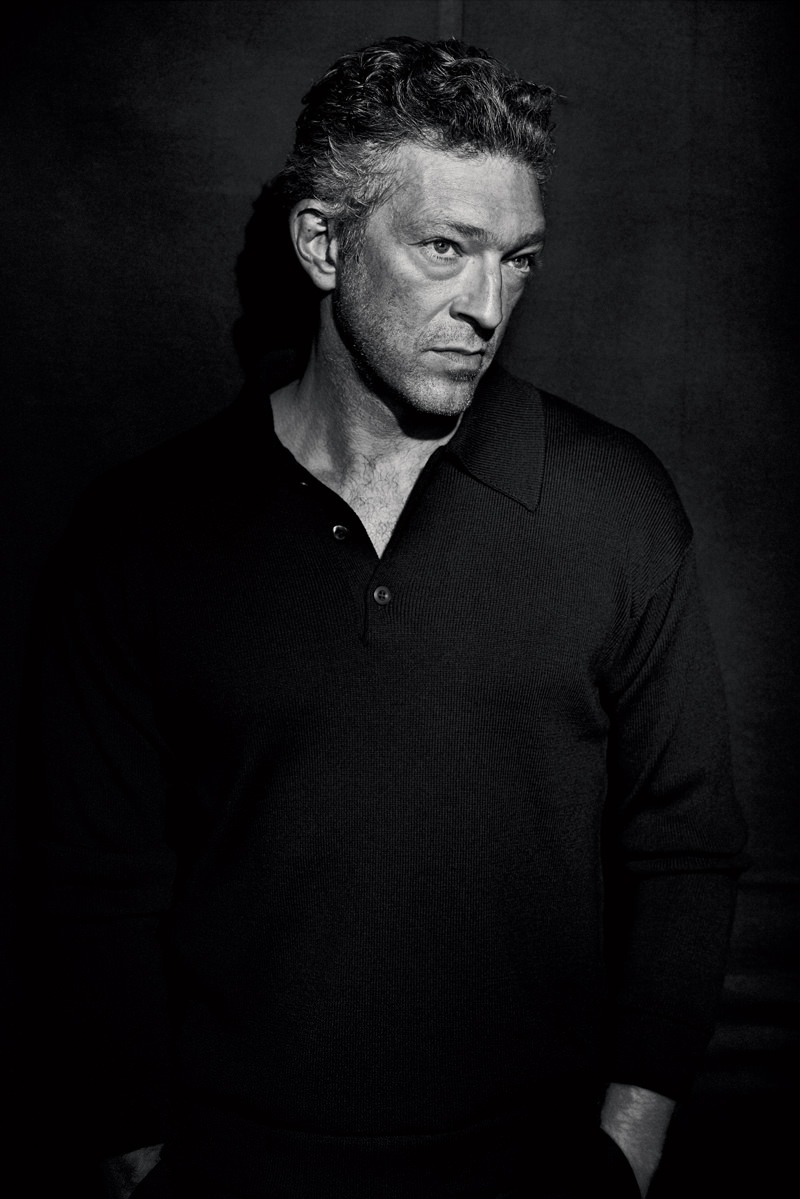

Interview with the irresistible Vincent Cassel

As he approaches his half century, Vincent Cassel is as troubling and seductive as ever. Currently starring in mon roi, maïwenn’s portrait of a passionate, tempestuous relationship, the french star told numéro homme about the fervent emotion of film-making.

Portraits by Peter Lindbergh,

Interview by Olivier Joyard.

Among his generation, is there a more desirable French actor? Some may quibble, but Vincent Cassel, who turns 49 in November, is up there at the top end of the not-solong list of charismatic male leads fabriqués en France. To start with there’s his filmography, which speaks for itself. From Jacques Audiard (Sur mes lèvres) to Steven Soderbergh (Ocean’s Twelve and Ocean’s Thirteen) via David Cronenberg (Eastern Promises and A Dangerous Method), Cassel has gone beyond his initial public image as a member of a young French film pack – alongside Mathieu Kassovitz, Jan Kounen and Gaspar Noé – to carve out a broader and far more unexpected career. Even with his flops – such as Blueberry or Sa Majesté Minor – he’s managed to hold his head up high with typical panache. In Mon roi, directed by Maïwenn and shown at this year’s Cannes Film Festival, he plays a man who is both scary and seductive, and whose relationship with his partner, played by Emmanuelle Bercot, is passionate and explosive. It’s ideal material for an actor who is very instinctive, often animal, and who can find the human qualities in violence, making audiences side with gangsters and misfits. Indeed his performances in L’Instinct de mort and L’Ennemi public n° 1 – Jean-François Richet’s diptych about notorious French bandit Jacques Mesrine – remain among his most memorable, and his resemblance to a frustrated dancer plays entirely in his favour. Today Cassel’s career is not only international but multinational. During our interview, just before jetting off to join Matt Damon and director Paul Greengrass for the fifth episode of the Jason Bourne saga, he explained that he was “going to carry on filming abroad: Italy, Spain, Australia and Brazil, where I live. I’ve already done two films there. I’m potentially a Brazilian actor, I speak the language. I’ve been going there for 30 years, so I’d be an idiot if I didn’t speak it!” Welcome to the all-or-nothing world of Vincent Cassel.

Numéro: Mon roi is a tale of coercion and dominance: your character wields power over the woman he seduces.

Vincent Cassel: I beg your pardon, but I never approached this role as that of a predator who’s found himself a poor damsel he can terrorize to satisfy his tortuous mind. For me this film was much more a love story. I tried to remain normal with respect to my character, without imagining someone with a narcissistic personality disorder. Relationships are always a bit violent when there’s passion involved. There can be a certain severity, both psychological and in the things people say, because they’re going through something very intense.

After the film was shown at Cannes, Twitter was abuzz with references to the idea of “perverse narcissism,” as though Mon roi were a social case study. It was women who were saying that, right?

Some of them end up saying that men are perverse narcissists when they think they’ve been had. You shouldn’t forget that the whole script is written from the point of view of a woman who’s taking tranquillizers and who’s beginning to lose control of herself. I always felt that Mon roi showed a rather distorted version of reality.

Like a hallucination?

Perhaps at times Emmanuelle Bercot’s character fantasizes about a male figure that doesn’t actually exist. I recognize myself in him, I recognize a lot of people in him, but he’s incomplete. We never see him alone, when the mask comes off. And it was a strong choice to show him like that. At the end of some of the scenes, the camera stays on him, and I don’t think that’s what works best. We should stay with the woman’s point of view. That’s why the film is called Mon roi: she’s the one who’s speaking. The guy is dazzling, a bit like an Italian, capable of risking everything to get himself out of a spot. He’s constantly jockeying and juggling. And at least he isn’t afraid of doing that.

With Maïwenn you have no choice but to ram right into the realities of life.

She puts you in situations and then asks you to explore them as you are. She shoots a lot of footage, knowing in advance that she’ll cut much of it. Inevitably she gets very natural, life-like reactions. There comes a moment on set where we’re not really acting anymore, but are defending a line of argument to someone. If we just followed the script, the scenes would take two minutes to shoot and she’d get bored. So we start inventing. Maïwenn wants to see how the situation she’d imagined can be given an authentic texture. The improvised scene won’t be any longer in the final film than in the script, but she’ll keep the essence of what happened “live,” all the accidents.

Does it bother you that a director keeps your acting “accidents”?

Nothing bothers me if I have confidence in the person who’s filming. It’s like with him [he nods towards Peter Lindbergh, who took the photos for the interview]. Really creative people don’t show up with preconceived ideas. They have a feeling. Then they play with what’s happening so as to go towards what they wanted to see. It’s always organic.

Between Dobermann and Black Swan, you’ve made films that are extremely different. Is their organic character what they have in common?

I deal better with cinema that way. I like it to be spontaneous. With Mon roi, I didn’t know in what order Maïwenn was going to put the scenes together, and that was great!

Does film making involve a certain amount of danger?

Not life-threatening danger. What you’re risking is your image. People are expecting something from you. I saw that, in one of her recent films, Catherine Deneuve sleeps with a monkey. I can understand why she did that. With the filmography she has behind her, she might want to do an offbeat movie like that. The only risk that actors really take is being ridiculous or just bad, and ultimately being out of work and considered a has-been. [Laughs.] What’s the point of only half doing things? I think it’s much more dangerous to do things for the wrong reasons, thinking that you’ll arrange everything so that it works out. On the contrary, if you’re a bit of a daredevil, if you play with fire, people respect you.

Do you feel the need to be protected by directors?

I need to know that the person directing me isn’t just trying to make sure their film will “work.” I look for people with a vision. There needs to be a bit of thought behind it all! Most of the directors I’ve worked with seemed to me to have that: Gaspar Noé, Jacques Audiard, David Cronenberg, Matthieu Kassovitz, Maïwenn. Have you seen Gaspar Noé’s Love in 3D? There are things you can do in painting that you can’t do in film. But with that movie he does them in film, and it becomes like a work of art. You may or may not like it, but it’s worth watching. I have a lot of respect for the stand Gaspar has taken since the beginning … Each time, he produces something that inspires others. That sort of hovering aesthetic he invented in Enter the Void has been used all over the place, sometimes without people’s even realizing it, because he has a pop influence.

Do you still think you’re part of a French cinema family? You started out with Jan Kounen and Mathieu Kassovitz.

There was a desire at the time, in the 90s, to make French movies that were different to what we were usually served up. But as they get older, people assert themselves and drift apart. In fact, families in cinema exist most of all when seen from the outside. People talked about a Nouvelle Vague family, but they were all constantly attacking each other. I would have liked to be in a cinema family… Except that getting films made is so difficult that you can’t work together just because you’re mates. A director, even if he’s a friend, hires you because he needs you, because you correspond to what he’s looking for, not because of the vacation in Corsica you went on together.

Actors have an important responsibility – if auteur films get made today, it’s often thanks to stars like you. An actor with a bit of fame can have that responsibility. I met Kim Shapiron, who directed Sheitan, when he was really young. I produced his film, I instigated it. But I always say that if a film doesn’t get made because I turned it down, then I was right to turn it down… If a director really has something to say, he’ll get there, whatever the conditions. In the “making of” for Apocalypse Now, which is great, you can hear Coppola, who didn’t know his wife was recording him, saying, “If I can’t get Marlon Brando, I’ll hire Martin Sheen, and if I can’t get Sheen it’ll be Jack Nicholson…” A film doesn’t depend on an actor.

Does that force you to be humble?

I know that everyone is replaceable. It’s part of my job to make people believe that I’m not, but really no one is irreplaceable. Even less so in the movies.

This year marks the 20th anniversary of La Haine, the film you made with Mathieu Kassovitz. It’s an anniversary that people have been talking about.

We’re coming out of that period, thank goodness. [Laughs.] I’m joking, I was delighted. It’s rare for a film to mark a whole generation. Following that experience, I’ve always thought you should trust your taste, rather than limiting yourself to what the market demands. La Haine was already about our times, but without the archaism of Islamic fundamentalism, and without all the technology – internet and cell phones. It’s an important film – I became conscious of that when it came out. It also changed my career. I thought I still had a few years to go in the wings when it came along.

Do you think you’re a better actor today?

I manage to get results with less effort. Before, I needed to get myself into all sorts of states. Now I get the same result more easily – I’m more relaxed, accepting, go-with-the-flow, non-judgmental. I’ve stopped bothering with the preliminaries.

You sound like a sportsman or a dancer.

I’ve always thought there were analogies between sport, dance and acting. A guy can train all he wants, but the day he has to jump he’s had a row with his mother, he’s got stomach ache from last night’s dinner, the wind’s in the wrong direction, he slept badly… but he has to produce his best performance. And that’s us a bit too. It’s at that precise moment, when you hear the word “action,” that the thing has to happen. It’s never predictable.

So you look for intuitive directors.

I don’t see how you can make good films without being intuitive. It’s impossible to do anything involved with the performing arts without that approach. Peter Lindbergh, Mondino, Cronenberg, Xavier Dolan… There’s always a certain amount of preparation you have to do with them that’s more or less complicated, but once you get to the performance it’s always fresh and alive. They know how to give themselves over to the moment and get the most out of it. And let’s not even talk about Gérard Depardieu, who has that in him.

You’ve just made a film with Xavier Dolan called Juste la fin du monde. How did that go?

Marion Cotillard, Gaspard Ulliel, Nathalie Baye, Léa Seydoux and me – that’s a pretty cool French line-up. I wasn’t supposed to be in it, but an actor left the film for a role I’d refused, which is funny. I have to say I can never thank him enough. Juste la fin du monde [which will probably be shown at Cannes next year] tells the story of a family, but like a Greek tragedy. Xavier Dolan knew exactly what he wanted to shoot. He had a certain budget and a certain amount of time, and he’d worked out and mastered the format of his film in advance. There’s thought behind it, an internal logic. Some directors have an aptitude, a talent, a certain weight that comes across straight away. I’m sure that Sergio Leone, on his first film, didn’t come across as a porn-movie maker! [Laughs.]

Would you say that you tell audiences something about yourself through your characters? Roles will often open a door into myself, an aspect of my personality that I’d never envisaged. I make sure the door stays open, I don’t close it again after the film. I know it’s there. There must be a certain logic, a colour, a flavour, if you line up my films one after the other. When I think about it, there are very few I could show my children. I told them that later they’d understand that their dad is a bit weird!

And these doors that you spoke of, what exactly do they open onto? Sometimes just a laugh. I remember that on Sheitan and L’Instinct de mort, I was laughing in a rather particular way. A sort of guffaw. Now I’m laughing like that again in real life. Thanks to the movies, I’m still discovering myself. There’s a whole part of me, a “manimal,” that I’m becoming aware of and that’s re-emerging.