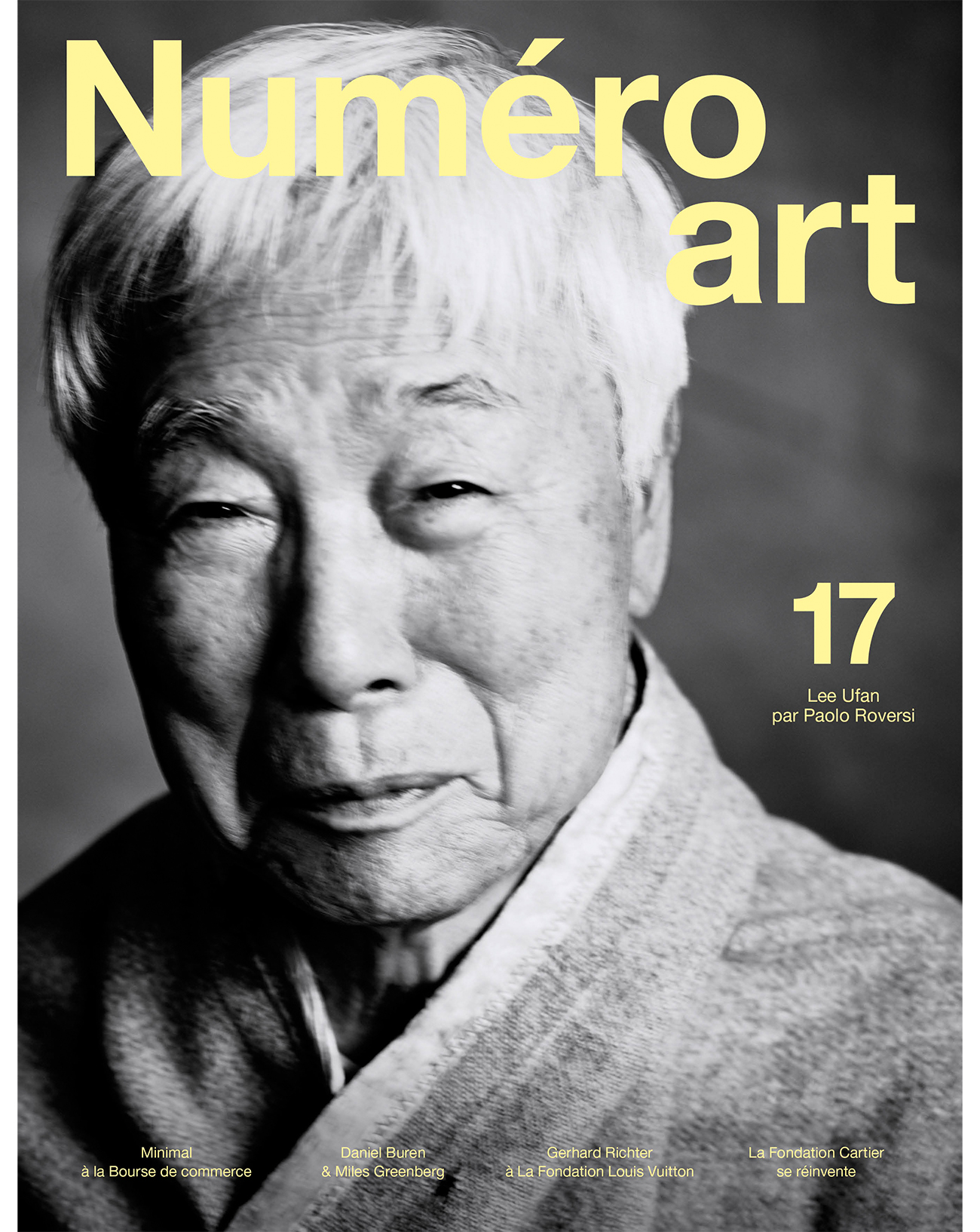

13

13

Interview with Björk: “I have a lot of hope in mushrooms!”

Björk is back: after a six-year absence, she has just released a new album, Fossora. Following on from 2017’s airy and ethereal Utopia, the Icelandic musician, who has been pushing the boundaries of her art for the past 30 years, digs down into the earth on her tenth opus, a tale of mushrooms and a return to our roots that she’ll be taking on tour across Europe this autumn. She opens up in an exclusive interview.

Interview by Matthieu Jacquet.

Published on 13 March 2023. Updated on 24 October 2025.

Numéro: For the past 30 years, with each new album, you transpose stories, themes, and new emotions into sound, melody, and image. How do you go about doing that?

Björk: When you’re a musician, there’s always this moment where, after touring your album for years and singing your songs over and over again, you come home exhausted and bored of expressing what you felt. Then there is this long time–often a year or two for me– where you don’t know what to do at all for the next album. That’s when I feel the most free and intuitive I invite the teenage part of me to find some clues and help me solve the riddle lying inside me. It can happen through looking at a colour or making a playlist… I start by adding all these new ideas until I call on the editor in me to analyse everything and throw elements away.

“Song-writing is very similar to friendship for me.”

Is that why each new album is always so different to the last?

Song-writing is very similar to friendship for me: when you meet a friend from your childhood, you both get very bored if you have the same conversations you had 40 years ago. Good friendships are the ones where you’ve totally changed and over the years you’ve moved on to new subjects, keeping it fresh and relevant. When I’m writing something and feel it’s starting to sound like an older song of mine, I decide it’s not worth it. There are already enough Björk songs in the world not to put out new songs that are similar to what I did before or to all the shit that’s on the Internet – which I think is amazing to explore. Though my albums are indeed very different from each other, there is a spine that makes them consistent : my voice, obviously, as well as a mix of electronic and acoustic sounds… It’s a bit like look- ing at yourself in the mirror when you brush your teeth: every morning, you wake up and look at the same eyes, nose, and lips. I really enjoy the fact that I have to work with what I’ve got as much as I like working around it – for example, I love changing outfits all the time.

On your new album, Fossora, mushrooms emerge as a major theme, both in words and images. What do you find so fascinating about them?

Mushrooms are about our neurological system, about healing as well. How they look, their energy, and how they travel is fascinating, and you can hear it in the beats of the album. Today, we’re discovering so much about fungi: in Chernobyl or other places where nuclear disasters happened, mushrooms are the first organisms to start growing again. In the environmental crisis we’re facing, I see a lot of hope in mushrooms. We should pay attention to the people who are studying them.

Family is also very present in the album. In two of the tracks, one sung with your son and the other with your daughter, you pay homage to your mother, who died five years ago. Is this opus a celebration of your origins?

The character of Fossora was born when I was burying my mother. It’s not a direct response to that, but everyone who loses a parent understands, afterwards, this need to dive into your past or your ancestors and reshuffle your position in the family tree. Where my previous album was about escapism and fantasy, about not dealing with family, roots, or day- to-day stuff, this new one was a way to dig into the ground. It’s not so much about Iceland as about not being able to travel and other circumstances that allow us to dig into ourselves. I could have written this album anywhere as long as it felt like home.

“Fossora was my way to return as a human being, on my own terms.”

Talking about home, after living partly in London in the 90s and then in New York for many years, you’re returned in Reykjavík where you now reside the whole year. The pandemic forced you to stay there for a long time. Do you still enjoy Iceland as much?

When I had a house in London or in Brooklyn I was still living in Iceland 50 percent of the time, so both those cities were my second homes. I love being in Iceland, so I was ecstatic when there was lockdown and I didn’t have to leave my home in Iceland and not even have to go to the airport was amazing. We didn’t have many restrictions here so our lifestyle didn’t change that much, we could go to the beach anyway for instance. For me, living here is definitely a way to get real. More selfishly, it makes for a very easy life to be in a village that is this size. I love the fact that if I want to go to a show, it is five minutes away. If I wanna have a philosophical conversation with a friend, I can text them and meet them by ten minutes at a cafe, and if I want to see the new Star Wars I can walk a few minutes from my home. With the weather and the fact Reykjavík is such a small town, it forces everyone to be very spontaneous. You don’t even organize things ahead here. If you say “you can come and have dinner at my house in a week” to an Icelandic person they will look at you like you’re crazy, like I did when I was talking to Londoners or New Yorkers! (laughs) Today, living here does not feel like I’m sacrificing all of those things I could do in big cities. It’s actually the other way around, now that many exhibitions, theater pieces, concerts come to Iceland, which wasn’t the case when I was in my twenties.

In 2015, when you brought out the album Vulnicura, you seemed very vulnerable, broken by your separation. Seven years later, you once again strip naked, but in a much less exposed way. Did writing this album allow you to take control again?

Probably, yes. Through my work I’m trying to document the different states that we, as humans, go through, whether we like it or not. What I experienced before Vulnicura was not a choice but a trauma, provoked by this surprising and unexpected situation that left me very unprotected. After that, Utopia came quite logically with the idea of escaping into the air, as a necessity. And then Fossora was my way to return as a human being, on my own terms. Staying home in my nest for two or three years surrounded by my friends and family allowed me to open up more.

Several years ago, you said that when you write your songs, melodies often came first to you and lyrics came afterwards. Since Fossora’s lyrics are very personal, especially about your family, did this song-writing process change?

It really varies. Mostly, the melodies come first and, if I’m lucky, the melody and lyrics come at the same time. Very often I have to make a jigsaw puzzle. With a song like Unravel on Homogenic [1997], I wrote the lyrics in my diary, had them there for a couple of years and tried to find the melody that was right but it wasn’t. Jóga was the other way around: the melody was running around in my head for two years and I kept trying different words to it. Then the chorus line “state of emergency” came as the last part, after many attempts. So I would say especially with Fossora, which took me five years to make, each song was written in a very different way.

“Even if my work doesn’t let it show, I’m actually a very down-to-earth and practical person.”

Several tracks on the album, like its first single Atopos, end suddenly with frenetic gabber beats [a type of hard-core techno]. Where did this idea come from?

I had this funny idea of Covid partying where you sit around with the ten people you can meet, very relaxed, and suddenly you stand up and dance for one minute before you sit back down. So the house you’re in becomes a club for one minute and then you go home early because of the curfew. To me this rhythmic structure was a bit of strange humour, like me making fun of myself. While writing the album, I was listening to bass clarinets, gabber, and a lot of music from East Africa. For Fossora, I planned to go to Barcelona and work with Arca, like I did for my two previous albums, but the pandemic kept us stuck in our cities. But then I had five years behind me, including three without being able to travel, so I started to write these songs where the rhythm starts very slow and then the beats double in the end, which was then enhanced by the beats added by Gabber Modus Operandi.

Which brings us to the fact that you’ve worked with a lot of different artists over the years, from the Inuit throat singer Tanya Tagaq to the hip-hop producer Timbaland. How do you manage to integrate all these very strong personalities into your universe?

I really love that part actually. Because I work so much alone, from the lyric and music writing to the arrangements, after three years I’m like, “Now, let’s throw a party and invite people over!” The older I get, the later I invite people in, so I can be better at explaining where I want to go and where they can find freedom in my project. For this album, most of my collaborations happened three months before I finished it. I was listening to some of my songs and thought we could make them more exciting. So I emailed Kasimyn [one half of Gabber Modus Operandi] to say, “I have this very strange album with bass clarinets and I programmed these gabber beats in a very simple way, could you add something to it?” He really got where I was going with Fossora. From Bali, he sent me ten beats, and I added and edited some into my songs, then sent them back to him, and he loved it. That’s also the reason I enjoy remixes of my work so much. While everything in an album can be quite strict and disciplined, it’s very liberating and nice to let another artist reinterpret your songs freely.

Since you released your first album in 1993, you have put out dozens of remixes of your own songs. You just released a remix of your single Ovule by Sega Bodega and Shygirl. Are remixes another way for you to get into this festive spirit you were just speaking about?

While making an album, all musicians have to commit to one version with specific instrumentations, arrangements, beats etc. You are very aware it is going to stay like that forever, so you have to pick the one that you think is the best one but also the one that hopefully can handle repeated listenings. Remixes are the opposite. After you have been more disciplined and restrained while finishing an album, it is kind of liberating to allow other people to take on it. There’no right or wrong with remixes, which I find iquite exciting. It reminds me of jazz from the 50s, where artists would play I don’t know how many versions of My Funny Valentine: even in the most strict finished songs, there is always one area that stays every free, where you can go anywhere. Remixes are also a fun way to get to know people, not just literally but musically. I had already met Sega and Shygirl but didn’t know them well, and their remix of Ovule really took it there! I then did a remix of Shygirl’s song Woe, which is not out yet, and it was really fun as well. I took Shygirl’s lyrics where she is asking questions in the choruses and tried to be the friend who answered these questions, so it became a lyrical remix, in a way.

You’ve clearly left the sugary celestial paradise of Utopia to descend below ground with Fossora – a neologism that for you means “she who digs.” Do these two albums form a sort of yin and yang?

Definitely. Even if my work doesn’t let it show, I’m actually a very down-to-earth and practical person, so I could only make an album like Utopia knowing I would balance it out later. I would say the previous album was about what sort of life I want ideally, and Fossora is about living it. At the moment, I’m editing the videos of Fossora into my live show Cornucopia, which I first created in 2019 and which I’ll be taking to southern-European stages in the fall. This show is probably the most the- atrical, expensive, and extravagant work I’ve done to date, so to justify making something this elaborate I would have to add another album into the setlist. I’m quite excited to replace the flutes and bird whistles of some of my most aerial songs with bass clarinets and gabber.

“Today, I no longer think one of my works is better than another .”

In your podcast Sonic Symbolism, which came out in August, you de- scribe each of your previous al- bums as a tarot character. Which character is Fossora?

In the podcast, it probably sounds like I’m a little girl and that my brain is very aware of what I’m doing. I’m actually sort of the opposite when I’m writing. It’s only three years later that I realize, “Oh, this is what the album is about and this is what I was doing!” To this day I’m still too close to Fossora to talk about it like this little girl, especially since I haven’t toured it yet. I can already tell you she’s a very earthy character, rooted in the ground, happy with what she’s got and seeing that as enough. As for the colours, I picture these dark greens and reds… But I’m sure that if you ask me in five years I’ll be able to tell you very clearly what this album is about!

This year marks the 30th anniversary of your first solo album, Debut. In 2004, you said your best album was still far in the future – is this still the case?

Today, I no longer think one work is better than another. And whether I’m 20 or 100 years old, whether there are seven or seven-million people listening to me, it’s all equally important. My show Cornucopia is probably the most extravagant I will ever do, but it doesn’t necessarily mean it’s the best to me. As terrifying as it may be, this uncertain moment before each new album is also very important. To be honest, I don’t know what I’m going to do next, and I don’t want to know, otherwise it would be very boring!

Björk, Fossora (One Little Independent Records), out now.

Björk’s 2023 Cornucopia tour includes three French dates: at Paris’s Accor Arena on 8 September; at Nantes’s Zénith on 2 December; and at Bordeaux’s Arkéa Arena on 5 December.