12

12

Elvis : interview with Baz Luhrmann, who directed the biopic on King of Rock Elvis Presley

Over the course of his career, the director of Moulin Rouge has brilliantly revisited the classic Hollywood musical, bringing it up to date while preserving all its poetic fantasy. His new movie, about the American rock star Elvis Presley, is on screens since June.

By Olivier Joyard.

Published on 12 July 2022. Updated on 20 June 2024.

At this year’s Met Gala in May, Priscilla Presley appeared on the arm of a handsome newcomer. In doing so, the King’s ex wife be- stowed her official seal of approval on actor Austin Butler, who gives a splendid performance as her former spouse in Baz Luhrmann’s new film Elvis. It was also a way of saluting the Australian director’s talent for glorifying larger-than-life characters. “The story, as we all know, does not have a happy ending,” she wrote on Facebook. “But I think you will understand a little bit more of Elvis’s journey, penned by a director who put his heart and soul and many hours into this film.” Over the last 30 years, Luhrmann has carved out a singular niche for himself in pop culture: a man who was perhaps born in the wrong era, he is an ambitious entertainer with grand visions and wacky ideas, obsessed with making movies that combine several genres and send us off into orbit with music. The director has both diehard fans and equally virulent detractors, but he leaves almost no one indifferent. His work verges on the kitsch, celebrates the impure, but also reveals the beauty of a world construed as an extravagant melody.

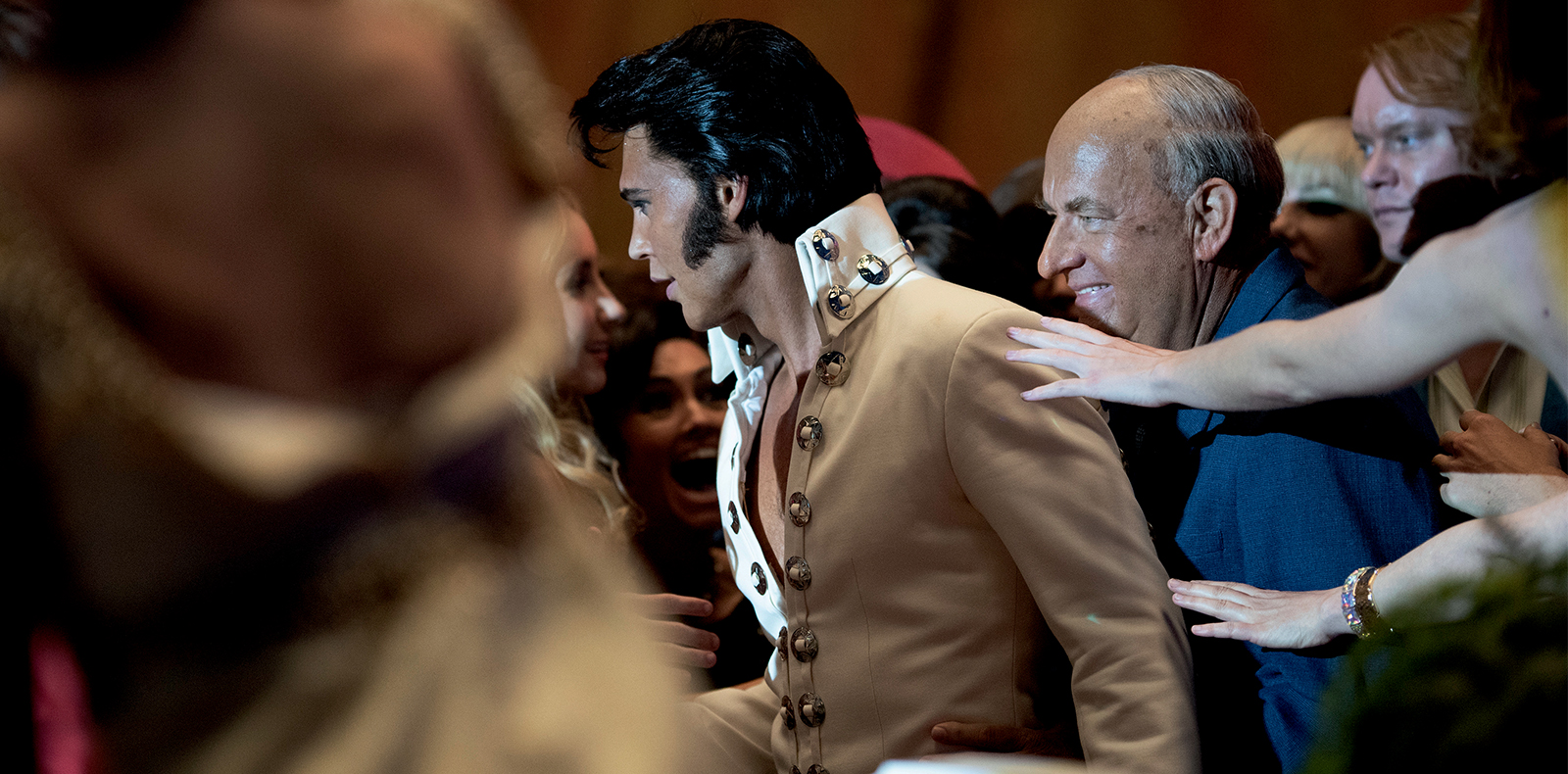

With Elvis, Luhrmann, who was born 60 years ago in New South Wales, is taking on a monument. But it’s the kind of challenge that clearly doesn’t daunt him, nine years after tackling F Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby with Leonardo DiCaprio, his biggest box-office hit to date. His vision of the rock ’n’ roll superstar, who died in Memphis in 1977, focuses on Presley’s relation- ship with his manager Tom Parker (played by Tom Hanks) in a long-haul narrative – two hours and 40 minutes – that attempts to foil classic expectations of the biopic. We follow the young Presley’s love for Black music, his early years of success, when he literally brought sex into pop music, before the long and inexorable fall from which he would never pick himself up. “I watched that skinny boy transform into a superhero,” says the voiceover as Luhrmann paints a cinematic portrait of Elvis as a contemporary god.

In Elvis, we follow the young Presley’s love for Black music, his early years of success, when he literally brought sex into pop music, before the long and inexorable fall from which he would never pick himself up.

In Luhrmann’s first film, Strictly Ballroom (1992), the hero, a ballroom-dancing specialist (just like the director’s mother), appeared as a sort of provincial Elvis, displaying an animality that this new film multiplies by ten and makes more spell-bind- ing than ever. Luhrmann is one of the very rare artists the film industry has given the means to take his obsessions all the way: binding sound and image in a dance without limits. It all began in early childhood when, on an isolated farmstead, he entertained friends and family with improvised musical shows. Later, his father would become the owner of a petrol station and a small local cinema. Luhrmann also watched television, riveted to the one channel that broadcast classic film and musicals. “When I was a child I loved musicals,” he recalled. “Very early on I saw Vincente Minnelli’s The Band Wagon [1953] and Top Hat [1935] with Ginger Rogers and Fred Astaire. My love of an artificial cinematic language that is capable of creating an identifiable emotion and a human experience was born then.”

On one of the logos for his production company, Bazmark, are several keywords that Luhrmann hopes to bring alive in an oeuvre that goes well beyond film – he has al- ready directed operas as well as one of Chanel’s most famous adverts, not to mention a series for Netflix. These words, which rule his imaginary, conjure up a beautiful simplicity: “truth,” “beauty,” “freedom” and “love.” On the logo, they feature alongside the saying “A life lived in fear is a life half lived,” which one might take as his manifesto – it has guided his career from the beginning. After the success of Romeo + Juliette in 1996, in which music was already very present, he began working on his life’s dream: directing a real musical so as to keep alive the memory of the child he once was, enthralled by the sounds and col- ours of classic Hollywood. His father died on the first day of the shoot, which he finally finished exhausted but happy. Moulin Rouge (2001) was a success that imposed on the world his version of an eternal genre, a re- mix of French operetta and the post-Broadway musical full of life and material. In the movie, Nicole Kidman and Ewan McGregor fall in love in a décor that is both clichéd and dreamlike, where Jacques Offenbach meets Marilyn Monroe, Nirvana’s Smells Like Teen Spirit fol- lows Elton John and Madonna, while Queen’s The Show Must Go On and Bowie’s Diamond Dogs get it on rockingly. Not to mention that the soundtrack includes one of the biggest hits of an already rich decade, Lady Marmalade, a cover version of Bob Crewe and Kenny Nolan’s 1974 track by Christina Aguilera, Lil’ Kim, Mya and Pink.

“Once I started to make movies,” he wrote in 2019, “I became obsessed with finding a musical language that could work for now. As someone who had loved musicals from childhood, I wanted to see them live again. So, in making Moulin Rouge, I set out with my collaborators to reinvent an old form. What I found was fundamental to all these films is that they aren’t psychological dramas. They’re not trying to hide the plot; it’s obvious. The art form is how you reveal that plot, heightening emotion through visual-language devices and, most of all, the music … Throughout the journey, there were moments when people in the industry who I genuinely respect truly believed that the musical could never be popular again. Now it’s uplifting that, more than 15 years later, the movie-musical is an important part of the cinema-going experience again.” Even if the director of Australia (2008) is perhaps viewing things through his own rose-tinted lens, it’s true that the first 20 years of the century have seen musicals back at the top of the ratings, such as the Step Up series in which classical dance met hip- hop. But the box-office failure of Steven Spielberg’s West Side Story, released at the end of last year, has nonetheless shown that an era has ended. With his latest opus, Elvis, which isn’t strictly speaking a musical but rather a picture about music and a musician, Luhrmann himself is perhaps confirming the idea that the golden age is behind him: one of his favourite movies, Star 80, Bob Fosse’s final feature film from 1983, was already bathed in an intense aura of melancholy.

To a certain extent, Luhrmann had already made his “final” great musical before Elvis. The Get Down ran for just 11 episodes, cancelled after its first season. But the Netflix series, broadcast in 2016–17, indelibly marked all those who saw it. A deep and joyous history of pioneers, it was set in 1970s New York, in the South Bronx to be exact, the Black and Latino neighbourhood where hip-hop was born. Ezekiel, Mylene, Ra-Ra and others discover their passion for the emerging music genre, trying to make it in an often-hostile environment at a time when the city was run by the Republican Ed Koch. Somewhere between fantasy and realism, an atmosphere crystallizes in which everything seems possible. Luhrmann, who had never tackled hip-hop before, was smart enough to surround himself with those who had lived through it first time round, among them DJ Kool Herc, Grandmaster Flash and Afrika Bambaataa, but also Kurtis Blow, Grandmaster Caz and Rahiem. Thanks to Nas, who was hired on the production team, the series mixed period tracks with new creations.

“What I found was fundamental to my films is that they aren’t psychological dramas. They’re not trying to hide the plot; it’s obvious. The art form is how you reveal that plot, heightening emotion through visual-language devices and, most of all, the music” – Baz Luhrmann

Christina Aguilera, Michael Kiwanuka and Janelle Monáe, as well as actors like Jaden Smith, also made a contribution – a question of credibility but also a sign of humility on Luhrmann’s part, the director finding just the right distance to evoke the Big Apple’s poor communities while showcasing the social dimension of his work in a more direct way than ever before. “Where there is ruin, there is hope for a treasure,” was the title of the first episode, and we wound up believing it. Constructed as long glissades of sounds and images, The Get Down’s episodes gave their director the opportunity to reach the summit of his style – a question of flow, which is the fundament of hip-hop. The dialogue may appear a little naïve, but is vital for the characters, whom Luhrmann showcases in suspended moments of song and dance.

Sometimes it’s in the seemingly “minor” works of the artists we love that we discover their true nature. Whoever watches The Get Down will learn to love Baz Luhrmann irresistibly. Except perhaps some of his employers: extremely expensive, with a budget estimated at over $120 million, the series was axed by Netflix at a moment when its director no longer had the time to devote himself to it fully, since he was already working on Elvis, a larger- than-life film adventure he began thinking about in 2014, and which is finally ready after the inevitable pandemic delays. The budget has not been disclosed, but it seems a fair bet that the director once again persuaded Warner to pull out all the stops for the King. With Luhrmann, the sky is always the limit, not through caprice but because of the intensity of his vision. His determination to ignore the codes of good taste goes hand in hand with this ambition. His is a total cinema, freed from rules and etiquette. “I’ve always been blind to the idea of high and low culture,” he once exclaimed, a statement worthy of the King.

Baz Luhrmann’s Elvis is out since 22 June.