She made her first notorious work at 21, in 1969, when she was still an art student at the University of Florida, but it was so misunderstood that she didn’t show it again for another 30 years. She’s barely known in France, where she’s only had one solo show (at Galerie Thaddaeus Ropac in 2001), but in the U.S. she’s always been admired, essentially by artists – of all generations, her own and those that followed. They didn’t abandon her when, in 1990, she was “thrown out of the art world,” as she puts it, due to further incomprehension of her work.

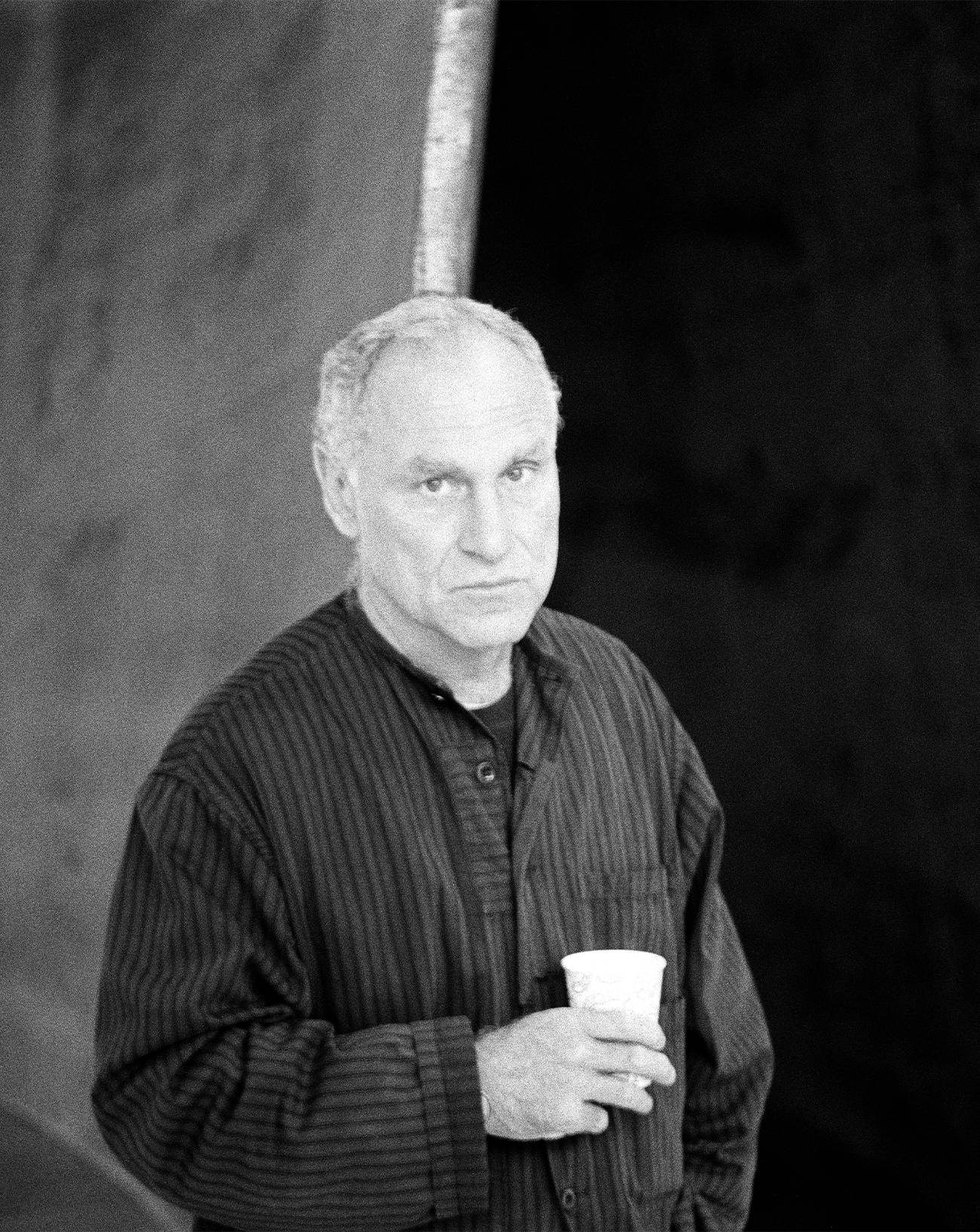

Her 2015 retrospective, Dirty/Pretty, which was shown at the Denver Museum of Contemporary Art, the Houston Contemporary Arts Museum and at New York’s Brooklyn Museum, put an end to all the misunderstandings, and, whether or not it By Éric Troncy is to one’s taste, amply demonstrated the perfect coherence and solidity of an oeuvre spanning 40 years. Now 71, Marilyn Minter has never sought success, but it has finally found her. “You don’t make art to be successful. If you make art for the love of it, then you’ll be fine, because even if you don’t earn any money, at least you’ll be making what you like. You’ll enjoy doing it.”

Minter was born in 1948 in Shreveport, Louisiana, and grew up in Florida. She exhibited a precocious talent for drawing and put her gift to profitable use when, at 16, she started faking driving licences – she was a dab hand at reproducing typescript with a pencil –, which earned her a few days in jail. The photos she made of her mother one weekend, while at art school in Gainesville, shocked her classmates, a reaction she didn’t expect. The 12 black-andwhite images (Coral Ridge Towers, 1969) showed their subject in her everyday idleness, lying in bed smoking, or dyeing her eyebrows, permanently dressed in a nightgown. “My mother was a drug addict. She never really left the house and almost always wore a nightgown ... She was a beautiful woman at one time, still very concerned about her looks, but a little off ... She was never quite right in terms of glamour,” explains Minter, who hadn’t foreseen that her photos would be interpreted as a damning portrait of their subject. So she filed the offending prints away, and didn’t show them again till 1995.

When she moved to New York in the 70s, Minter started producing work in a register that she ironically describes as “boring photorealism,” which, she says, was a reaction to the vivacity of 60s photorealism and to the conceptual tendencies then proliferating in the Big Apple’s art galleries. Her paintings show subjects such as a pair of black-and-white photos throw down onto a grey lino floor (Photos on the Floor, 1976), a crumpled piece of aluminium foil on the same floor (Aluminum Foil, 1976), the corner of a sheet of plywood, an eggshell and an old sponge in a stainless-steel sink, and other such unglamorous, unheroic banalities. She exhibited them without frames or chassis, simply stapled to the wall. In the 80s she teamed up with German artist Christof Kohlhöfer, who had worked with Sigmar Polke, and thus became familiar with some of Polke’s techniques, like the projection of an image so that it appears exaggeratedly enlarged. An oeuvre, in other words, that showed her ambition to explore the avant-garde art forms of her time, but which was still a million miles from the universe she would go on to develop at the end of the decade.

“Did Minter have to show women doing the cooking and transformed into sex objects without the least critical distance with respect to the violence of the subject?”

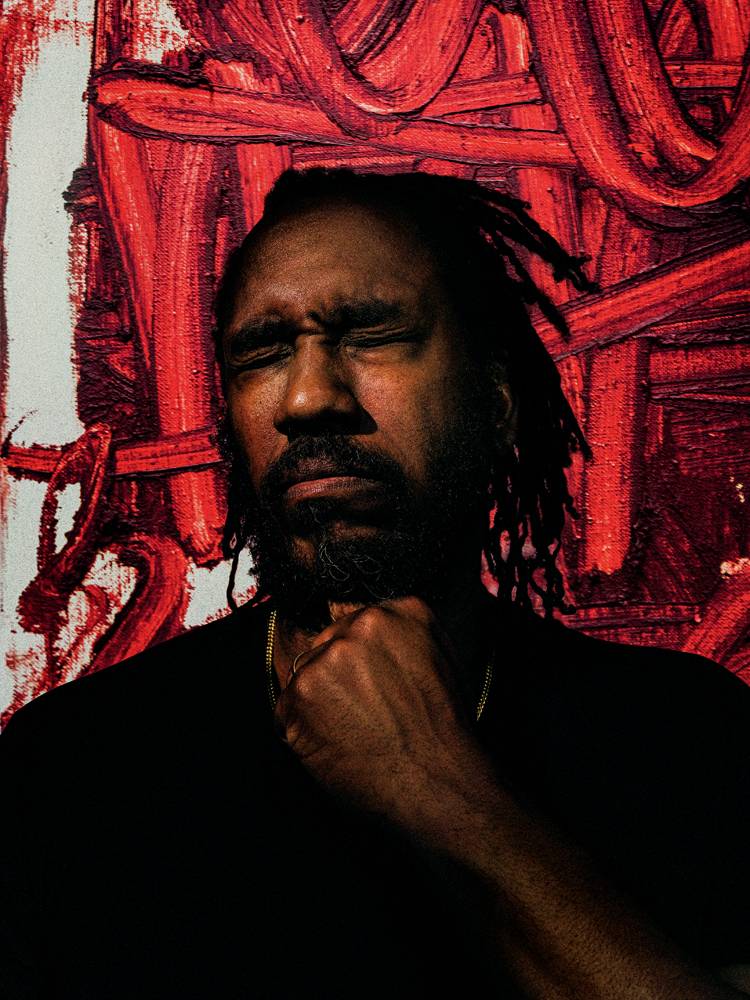

The late 80s represented a major turning point for Minter, who looked around to see which subjects women artists hadn’t yet tackled, and came up with an irrevocable answer: hard porn. So began her series of paintings drawn from pornographic imagery, such as Porn Grid (1989). Determined to ignore conventions, including the traditional exhibition adverts in the art press, she chose to promote a 1990 show she was preparing at the Simon Watson gallery with a 30-second video that was aired on primetime TV, in the ad breaks of broadcasts such as David Letterman’s Late Show, at $1,800 a slot.

100 FOOD PORN, as it’s titled, showcases pictures inspired by food photography: red-nailed fingers separating eggs or shelling shrimp, all realized in a Pop manner with abundant paint drips and half-toning dots that reveal their printed-matter origins. The video, which must surely have been a first, seems with hindsight to be a violent commentary on art’s future as entertainment. “If you didn’t know what it was about, you’d probably not have guessed,” explains Minter with respect to the entirely Surrealist effect of that particular film being shown in that particular context. Feminists saw in it something other, which was a lot less acceptable to their eyes: did Minter have to show women doing the cooking and transformed into sex objects without the least critical distance with respect to the violence of the subject?

But that is precisely Minter’s trademark: nowhere is there any form of commentary in her work, a problem in a period when art was all about the politically correct. And so, once again, America reacted unfavourably to her work. “I felt like I got thrown out of the art world,” she declares as she recalls how her gallerist, fed up with the controversy, closed the Food Porn show a week early. She also remembers the unfailing support of her artist friends: Cady Noland, Larry Clark, Jack Pierson, Jessica Stockholder, Laurie Simmons and Mary Heilmann, among others. “Well-known artists. But there was a time when they couldn’t even defend me because it was too dangerous for them,” she remembers.

“I don’t really think it’s interesting to make another pretty face or another good-looking ad. I just want to make a picture of what it’s like to live in a world where you’re constantly bombarded with images and they’re not necessarily precious anymore.”

The controversy of course had no calming effect on Minter, who, true to form, pushed things even further. The year after her Food Porn series, Jeff Koons would unveil his first couplings with La Cicciolina… But Minter just carried on doing what she liked. “And in 1995, when I showed the pictures of my mother, I got let back in. I think that the culture trusts artists who come from dysfunction. Somehow this legitimizes the work,” she explained to Glenn O’Brien a few years ago. Since then she has been producing a body of work that is in every way faithful to her original intentions, and comprises photographs (in small quantities and never retouched), videos (essentially for commercial events) and garish paintings inspired by fashion and porn photography.

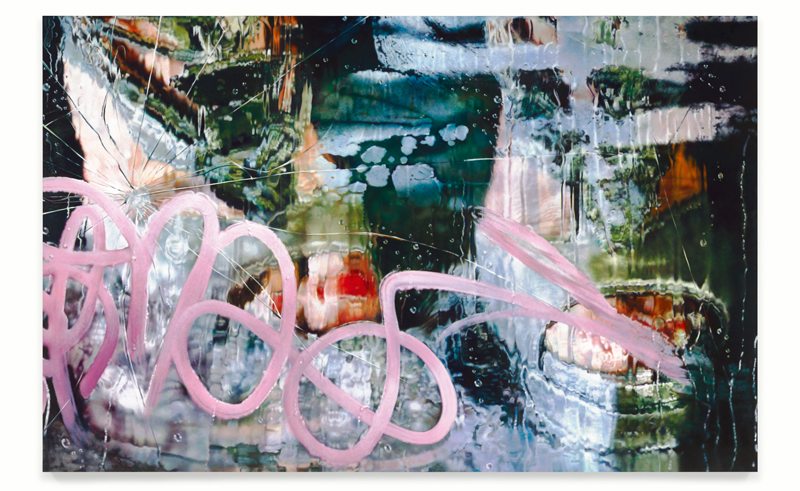

She mostly works on metal, uses her fingers rather than brushes, and musters all the patience necessary to apply layer after layer of paint. “There is a depth, a richness in a painting that you could never get in a photo,” she explains. Unlike her photography, her paintings are drawn from countless shots that she takes herself and then assembles in Photoshop. As of 2009, her images seem as though realized behind a sheet of glass, giving them a feeling of both proximity and of distance, like a bus-stop advert that’s been graffitied, or a wet shower screen covered with droplets of water. Her subjects – not only women, she insists – are not exactly shown in a flattering light. “I don’t really think it’s interesting to make another pretty face or another good-looking ad. I just want to make a picture of what it’s like to live in a world where you’re constantly bombarded with images and they’re not necessarily precious anymore.”