8

8

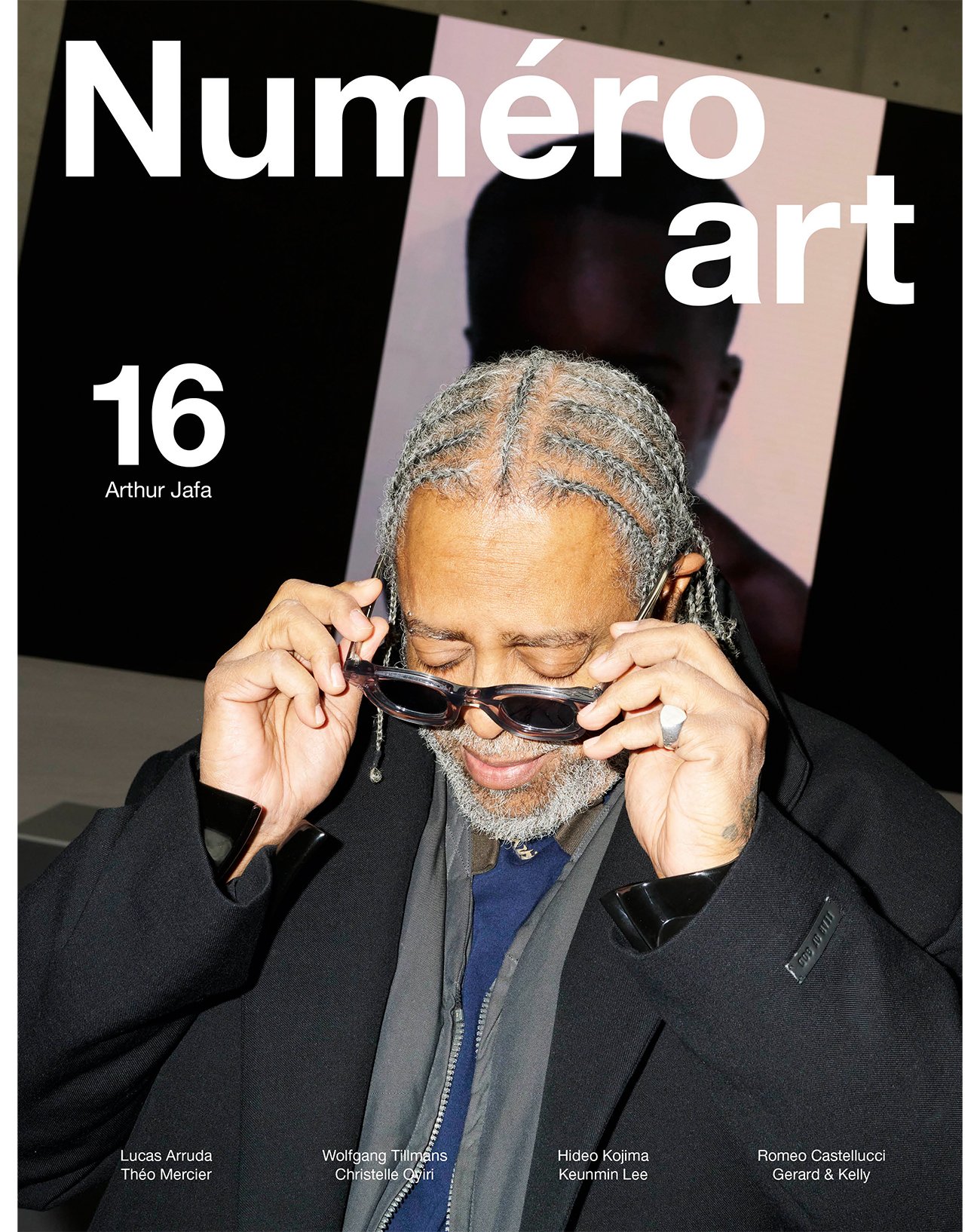

Between video games and mangas, how does the artist Sara Sadik stage the “beurcore” culture

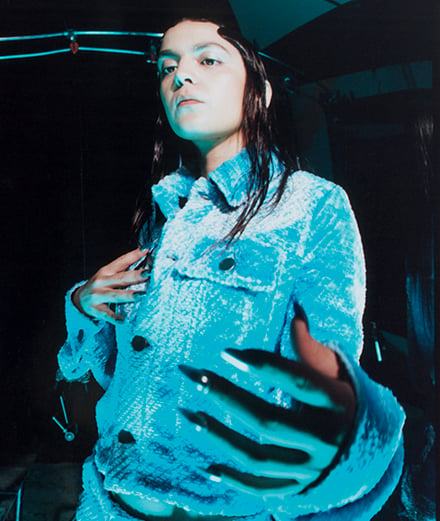

Like no other, she transmutes the culture of France’s young Maghrebi diaspora into contemporary art, producing initiatory video works that are inspired by popular computer games, music, anime and manga.

Portraits par Lee Wei Swee,

Texte par Félix Boggio,

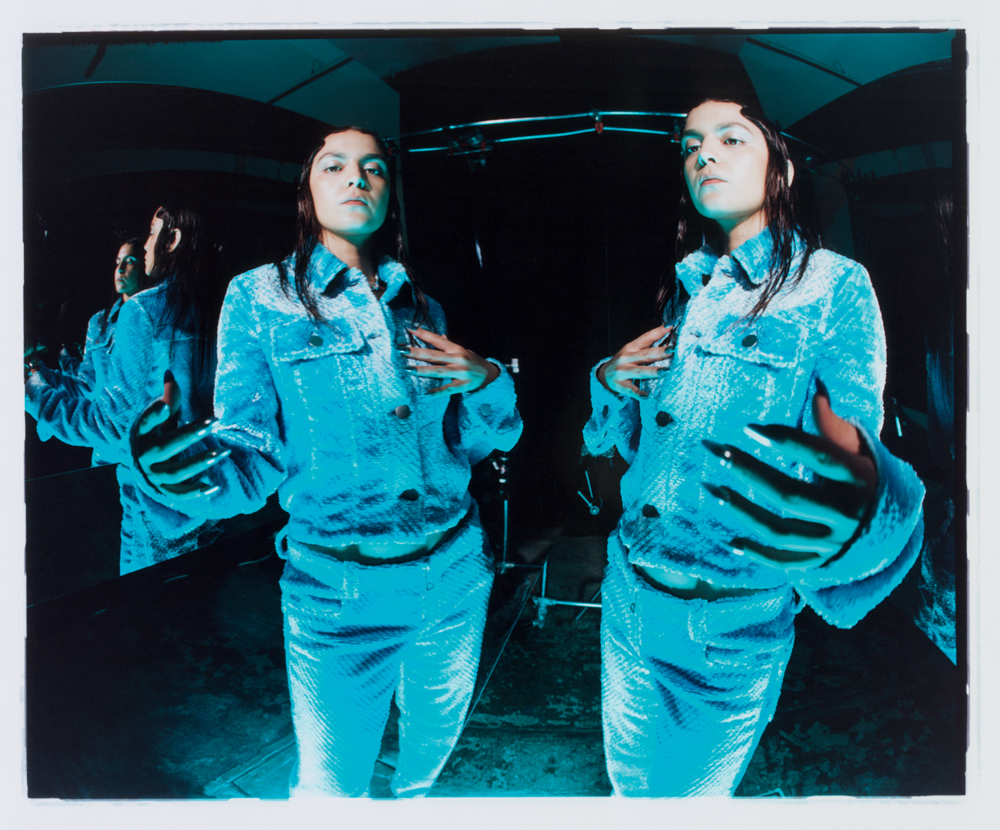

When asked the meaning of the term beurcore, which she uses to describe her art, French artist Sara Sadik replies: “It’s a word I came up with to describe what I do, to cut to the chase and avoid having it defined for me with words that aren’t appropriate. I wanted a term that sounded ‘powerful’ and was easy to remember. The suffix ‘core,’ which is mostly used in music, allows both. Beurcore is the culture of the young Maghrebi diaspora in France at its most emblematic. For me it’s something that already exists but hasn’t yet been defined, other than with the catch-all term ‘urban culture.’ It’s both what is created and consumed by this section of society.”

“Beurcore is the culture of the young Maghrebi diaspora in France at its most emblematic. For me it’s something that already exists but hasn’t yet been defined, other than with the catch-all term ‘urban culture.” – Sara Sadik

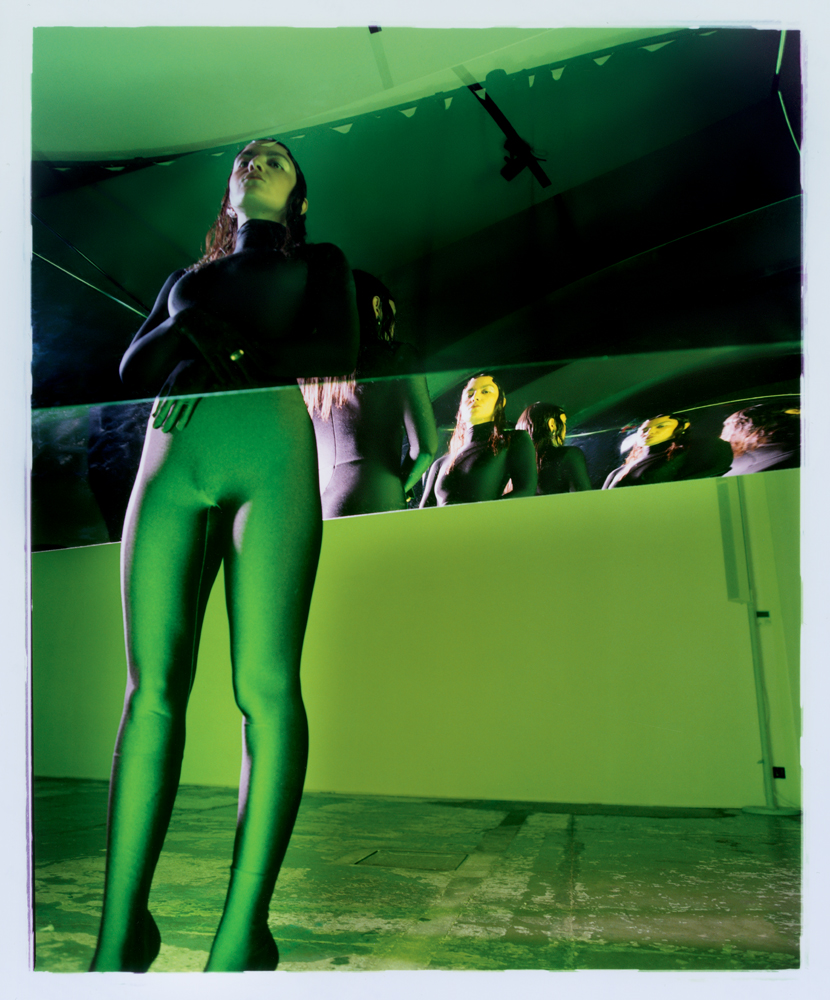

Sadik’s work, which has been compared to Afrofuturism, belongs to a community culture, which she brings to life in contemporary art with references from French hip-hop catch lines, popular video games, anime and manga. Her work is not just collage or pastiche, however: her narratives frequent- ly take the form of journeys of initiation, not only in the manner of the coming-of-age novel, but, more surprisingly, like occult rites of passage. Her narrative is neither the Bildungsroman of “young people from disadvantaged neighbourhoods,” nor an introduction to ghetto culture for white spectators, alien to the subcultures of immigrant children, who are taken by the hand to visit the zoo. The presence of the occult has to do with the transformative vocation of Sadik’s art. In this re- spect, it wouldn’t be overdoing it to describe her as a mod- ern-day alchemist, given that her work “transmutes” her raw material so that the spirit of it appears in the things them- selves: for example the taga (cannabis resin) that permeates the soil of the utopian oasis Zetla Zone, or the soda springs that irrigate it – like an elixir of life or the abundant sweet waters of the Kawthar (river of paradise, hadith no. 3,361).

Works such as Tu deuh la miss, Hlel Academy and Carnalito Full Option are as much situations as they are films (set in prison where Carnalito is concerned) – situations that Sadik invented to transmute the soul. Dressed like a TV presenter, she takes on the role of the hierophant, putting young men to the test not only through their physical prowess but also through their capacity to love, in a setting that, while certainly futuristic, invariably oscillates between reality TV and mystagogy (initiation to the Mystery).

Sara Sadik’s artworks are as much situations as they are films situations that Sadik invented to transmute the soul.

Là encore, derrière le pastiche apparent se distingue la densité du mystère. Les épreuves accomplies lors de performances et filmées ne doivent sans doute pas être lues au premier degré, comme une évaluation des forces et des faiblesses des candidats (le plus souvent non blancs et descendants d’immigrés), mais comme le texte symbolique d’une entrée dans un espace radicalement autre, dans lequel le virtuel devient réalité et se dresse contre la réalité apparente où toutes les valeurs sont inversées.

Here again, behind the obvious pastiche, we find the density of the mystery. The tests that the participants are asked to carry out in these filmed performances shouldn’t be taken entirely at face value: rather than an evaluation of the candi- dates’ strengths and weaknesses – candidates who are for the most part non-white and of immigrant descent –, they are the symbolic text of entry into a radically different space, one in which the virtual becomes reality and stands up against apparent reality, in which all values are reversed. Too often, the violence of poverty and racism is analysed in terms of its economic and social consequences. But it is just as much a crisis in the value system, an insidious process of desymbolization. Cultural and religious repression strives not only to exclude but also to foreclose any sense of com- munity underpinned by symbols. When the far right at- tempts to define France according to its Judaeo-Christian roots, it is in fact seeking to deprive non-whites of any symbolic status within the national narrative.

Re-populating the post-colonial desert through dreams and symbols is clearly the ambition behind Sadik’s affirmation of the virtual – which can be understood in its philosophical sense as a field of possibilities, but also, more prosaically, as immersive multimedia. Long before the appearance of com- puter-generated reality, this third space was the result of vi- sionary experiences resulting from initiation rites – and therein lies the hidden meaning of the great symbols of spiritual chivalry, such as the quest for the Grail, the philosopher’s stone, or the lady, or the encounter with the angel.

She succeeds in transforming these “shameful” cultural industries into an alchemical laboratory where lead can be transmuted into gold.

For Sadik, the event as resymbolization is thus opposed to the spectacle-event, whose sole virtue is, at best, to alleviate boredom. In Khtobtogone, thanks to the powerful game engine of Grand Theft Auto, Sadik’s “augmented” reality brings to life a Marseille environment in which the protagonist, a young man from a disadvantaged neighbourhood working as an Uber delivery boy, painfully negotiates the meaning of life between his (chivalrous) loyalty to the male world of the street and his (in reality no less chivalrous) commitment to love. Opening this trans-dimensional door, Sadik makes a mockery of conventional hand-wringing over the moral failure of today’s youth in a world of brainless influencers and ad- vertising algorithms. She succeeds in transforming these “shameful” cultural industries into an alchemical laboratory where lead can be transmuted into gold. This is how the allegorical charge of rapper Jul’s two catchphrases can be read: “D’or et de platine” (“In gold and platinum”) and “On m’appelle l’ovni” (“They call me the alien”).

For the alchemist’s gold is not simply a precious metal, nor is the purification of minerals a mercenary process. Alchemists sought to create a perfect mirror for the light of the human heart – the brilliance of gold as a divine signature. No one really knows what the philosopher’s stone was, but Michael Maier wrote that it was “a vile and worthless thing, trampled by the passage of travellers, all the way to the dunghill.”

In Sadik’s work, the brilliance of love dissolves the material anchorage of the “pop” and the “urban” (or its vocation as a sociological object) to attain the ethereal sky of the alien.

How does Sadik go about transmuting the ter-ter (neighbour- hood), that thing of little value, so as to welcome the alien? As in all mystagogy, love plays a key role in this miracle. One might have interpreted this theme in her work from the angle of the emotional deadlock of segregation and poverty, but it also seems desirable to insist on the allegorical value of the amorous union, like the figure of the marriage of the sun and the moon for alchemists, which symbolized matter coming to life in their laboratories. In Sadik’s work, the brilliance of love dissolves the material anchorage of the “pop” and the “urban” (or its vocation as a sociological object) to attain the ethereal sky of the alien, where the destiny of the Earth’s damned finds its redemption in the figure of the angel – or of a Super Saiyan hovering among the clouds.

Sara Sadik has presented a video during the exhibition Des Corps Libres – Une jeune scène française, May 5th-28th, Studio des Acacias, Paris. She is represented by the Crèvecœur gallery (Paris).