London has become obsessed with its own disappearance. Excavations for high speed transport networks and luxury developments destined to make London the city of the future have done an excellent job of pulverising its (colourful, countercultural) past: recording studios, drag cabarets, music venues, gay clubs, independent cinemas, book stores and cafés have all felt the impact. Many have shut for good, moved out or moved online.

In Mayfair, traditional home to the grown up ‘moderns and masters’ art market, luxury fashion is pushing out the galleries. Big brands can cope with rising rates: small art galleries cannot. The hip young independent galleries have long since fled to the city’s marginal spaces, clustering in Mile End, Peckham, and Elephant & Castle or squeezing themselves into overlooked corners in the city centre: Soho yards scented with weeping trash, or dusty, failing high street storefronts.

Project Native Informant occupies a small former office suite in a disused corporate block in the legal and financial district. On a bright summer day, sun blasts through the glass walls. No longer luxuriating in corporate aircon, the temperature of the space is intolerably high. Their show, though, is heat-appropriate: sultry vinyls and drawings of 1980s fashion vixens by the Japanese artist and illustrator Harumi Yamaguchi. Re-carpeted in fuchsia pink, with walls painted in gradiated seaside blues and yolk yellow, the tatty corporate office is transformed into a site of fantasy for a girl trapped in a nine-to-five. Learning to exploit such unconventional spaces is a key component in the independent gallerist’s skill set.

“It’s strange to note how on one hand, business is good because our clients are much less affected by austerity, but on the other hand most of my artists have left London because they find the situation unliveable here.” Vanessa Carlos, director of Carlos/Ishikawa

Vanessa Carlos, director of Carlos/Ishikawa, a dynamic young gallery nestled beneath a public housing estate in Mile End, describes how London’s blooming wealth has become a double-edged sword. “It’s strange to note how on one hand, business is good because our clients are much less affected by austerity, but on the other hand most of my artists have left London because they find the situation unliveable here, and my rent is going up 65 per cent at the moment alongside the fast-paced gentrification that is happening in our neighbourhood.” The lack of affordable studio spaces driving artists out of town is in turn piling additional travel and shipping costs back onto their London galleries.

As the traditional galleries in the city centre are squeezed out by rising rates, the international mega galleries are moving in. Earlier this year, Thaddaeus Ropac opened a space on Dover Street the size and glamour of a nineteenth century department store. David Zwirner’s handsome townhouse gallery – opened in 2012 – is just up the road. Nearby are London digs for Pace, Gagosian, and a host of other US and European heavies.These galleries may not be fighting the younger galleries for space, but they pose a threat in other ways, scooping up artists nurtured and supported over many lean years just as they reach an attractive stage of marketability. There must be something a little terrifying for these galleries about representing an artist that suddenly becomes a ‘name’.

Much like the ability to work with peculiar spaces, the answer for many independent galleries has been to champion artists that don’t fit neatly into the established galery template: collectives, such as åyr, DIS, and Shanzhai Biennial (represented by Project Native Informant) or the Lloyd Corporation (Carlos/Ishikawa); artists working in less easily commodified media, such as Instagram subversive Amalia Ulman (represented by Arcadia Missa); late career artists ripe for recognition. Female artists, still under-represented at the top end of the market, are in the majority at both Arcadia Missa and Holybush Gardens.

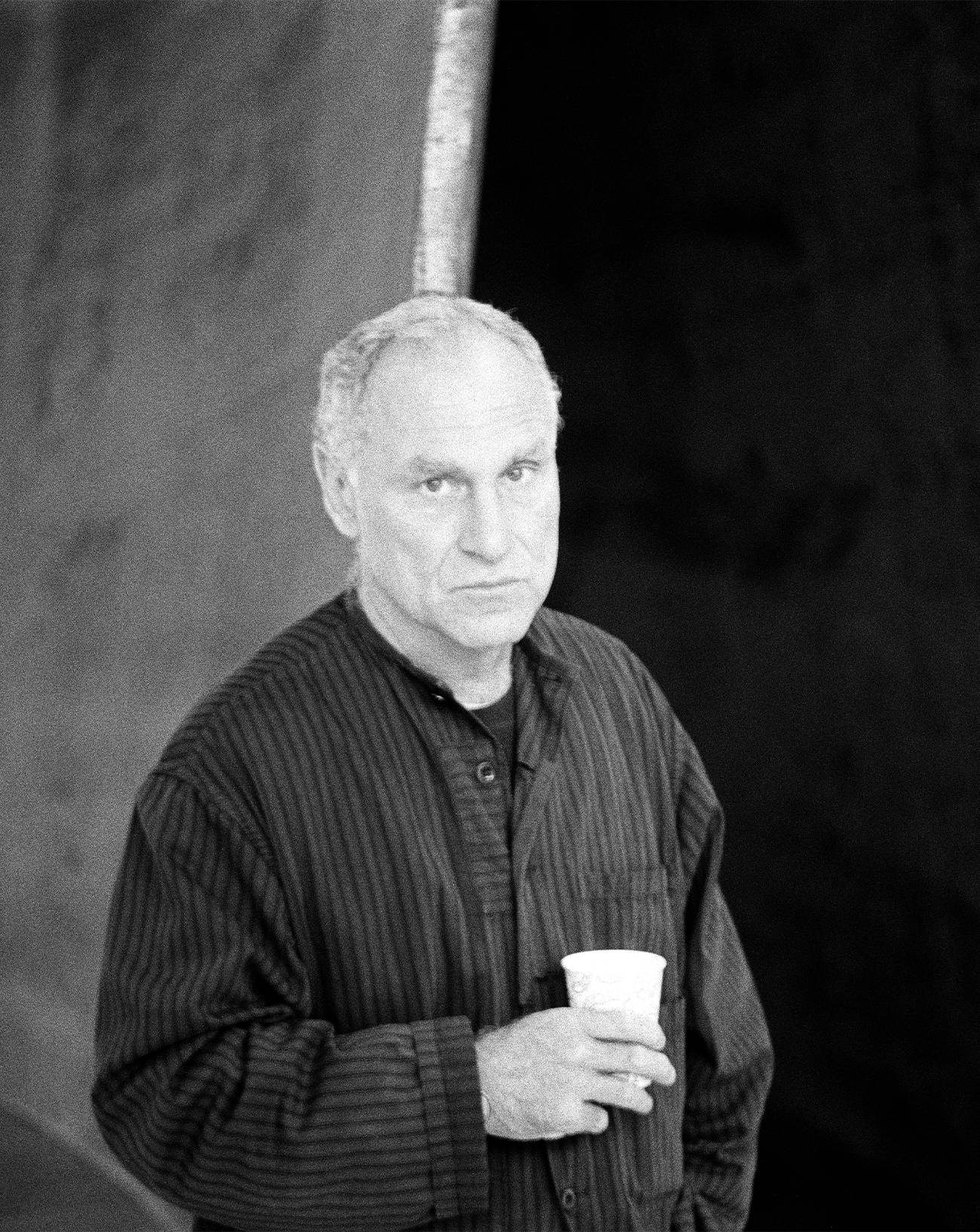

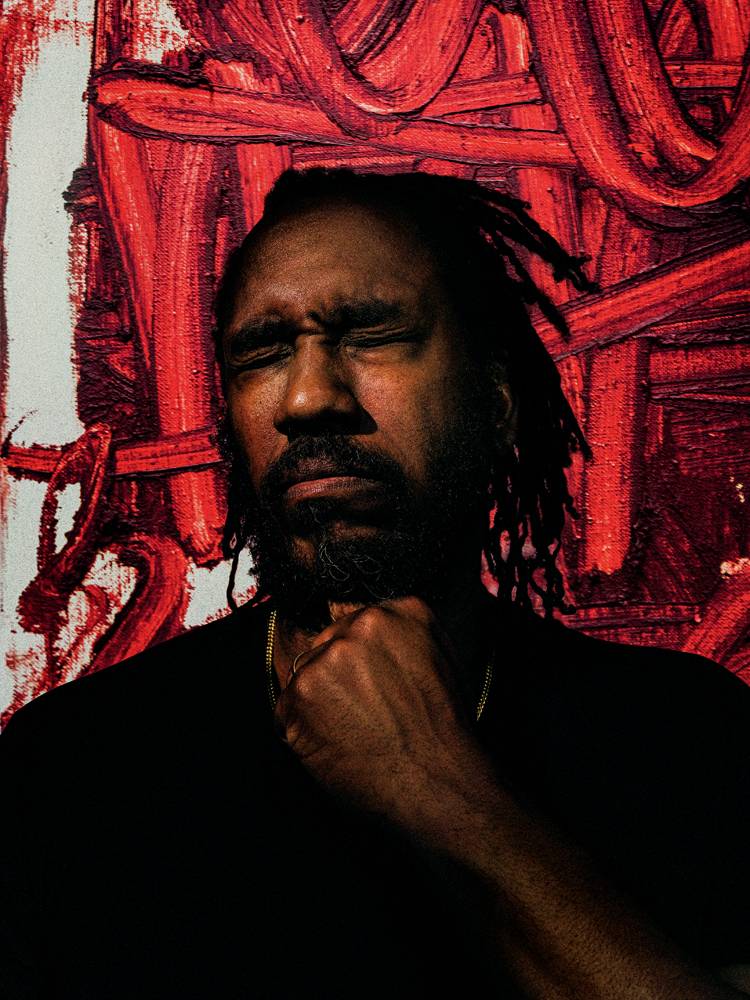

Lodged in an old coach house in Clerkenwell, Hollybush Gardens has two artists shortlisted for this year’s Turner Prize: Andrea Büttner and Lubaina Himid. Lisa Panting and Malin Ståhl started the gallery twelve years ago in Bethnal Green. “I think we were lucky to open in 2005, and not a couple of years earlier,” says Ståhl. “It felt like there was such a rush then. Collectors were really buying young artists, and I think a lot of young galleries made a lot of money. Then came the crash: I think that was very hard for a lot of people.” Instead Panting and Ståhl maintained modest expectations, running day jobs alongside the gallery to fund exhibitions, and only becoming self-sustaining in 2010.

It is in working together to build new audiences, new collectors and an alternative international scene, that independent galleries are holding their own against the rapacious corporates.

Their decision not to chase the bottom line has allowed them to pursue artists they felt passionate about. They came across Himid’s work in a book about the Black Art Movement and ended up contacting the Preston-based artist for a studio visit, staging her first ever show in a commercial gallery in 2013, when the artist was 59. “From what we’d read about her, looking at her work dating back to the 1980s, we thought that she seemed like such an important person,” says Ståhl. “We thought that she should have a lot more visibility.” Their broadening of focus has had an impact: the Turner Prize jury this year lifted their age limit, making Himid, at 63, the oldest artist ever nominated for the award.

While initiatives are in place to promote the buying and selling of art online, despite London’s prohibitive rates, bricks and mortar spaces are still important. Rozsa Farkas started Arcadia Missa in a tiny space in Peckham soon after graduating in 2011: “I wanted to still have a physical place of assembly; a place to discuss ideas including those that were happening between peers online,” Farkas explains. “I moved to become a commercial gallery representing artists at the end of 2014, so we aren't exactly a huge business, yet the great thing about running your own space is the autonomy I have in terms of who I show - I get to work with artists whose work I am a massive fan of, whose work moves me, whose work engages with the world outside the gallery walls.”

The evolving art market had seen the nature of the gallerist’s role shift dramatically. Stephan Tanbin Sastrawidjaja, founder of Project Native Informant, admits that much of his energy is spend raising funds for his artists’ public exhibitions and biennial projects, among them the 2016 Berlin Biennale curated by DIS. While established art fairs such as Liste in Basel have provided important international exposure, Sastrawidjaja has also built a presence for the gallery in Asia, showing at West Bund Art & Design in Shanghai as well as Art Basel Hong Kong.

It is in working together to build new audiences, new collectors and an alternative international scene, that independent galleries are holding their own against the rapacious corporates. In 2016, Vanessa Carlos launched Condo, an initiative that invited galleries from out of town to collaborate on shows with London spaces in the quiet month of January. A successful second run in 2017 saw partner galleries coming in for as far away as Guatemala, and a party spirit pervading: the first New York edition ran this summer, and editions in Shanghai and Mexico City have been announced for 2018. “A lot of the inherited models from the 1990s that my generation has been left with aren’t really functional for us anymore,” says Carlos. “The Condo project has collaboration and generosity at its core, and aims to encourage conditions that are more conducive for artists’ experimentation. In the world at large, how do independents survive in relation to corporations? They collaborate or conglomerate.”