3

3

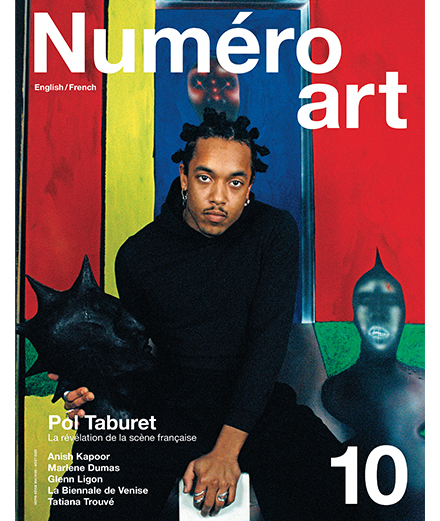

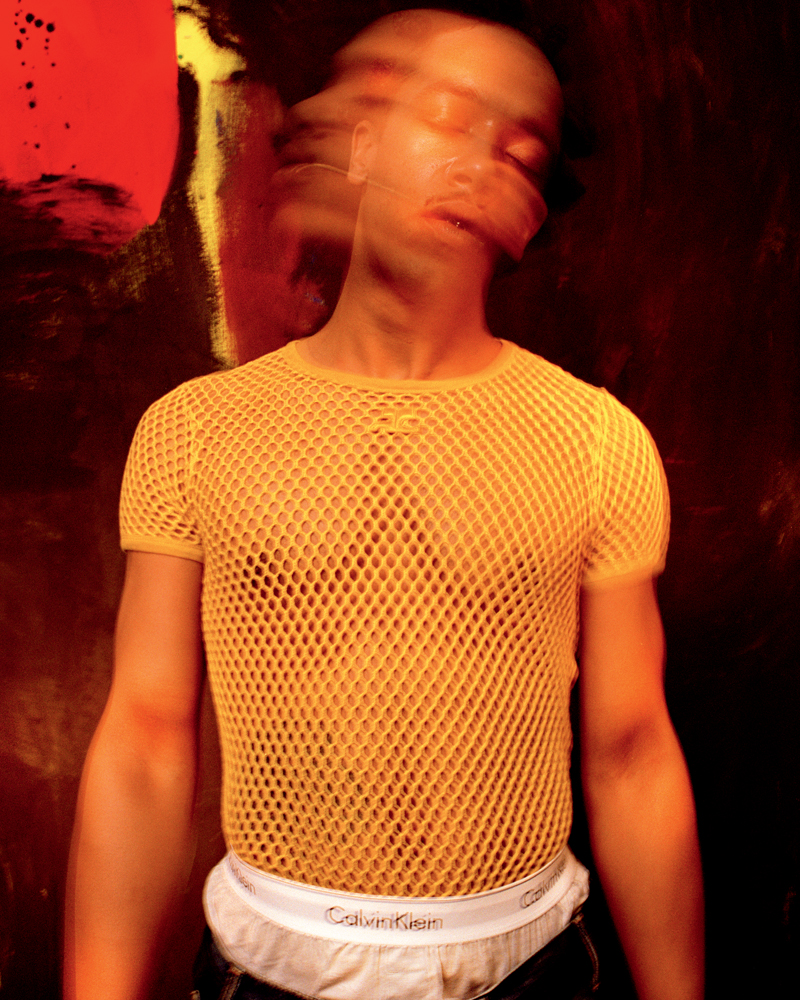

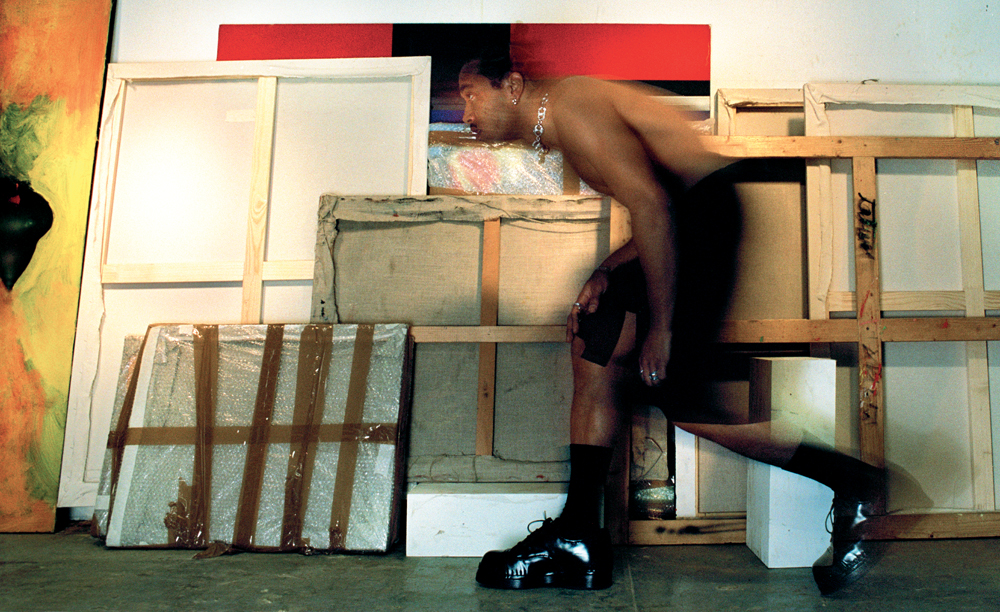

Pol Taburet, revelation of the French art scene on the cover of Numéro art 10

In his hallucinatory canvases, the young French painter mixes rap, subculture and the occult power of creole quimbois. Winner of the Reiffers Art Initiatives prize for young talent and cultural diversity, Pol Taburet is showing his work this May in the exhibition “Des Corps Libres” at the Acacias Art Center.

Photos by Hugo Comte,

Text by Juliette Lecorne.

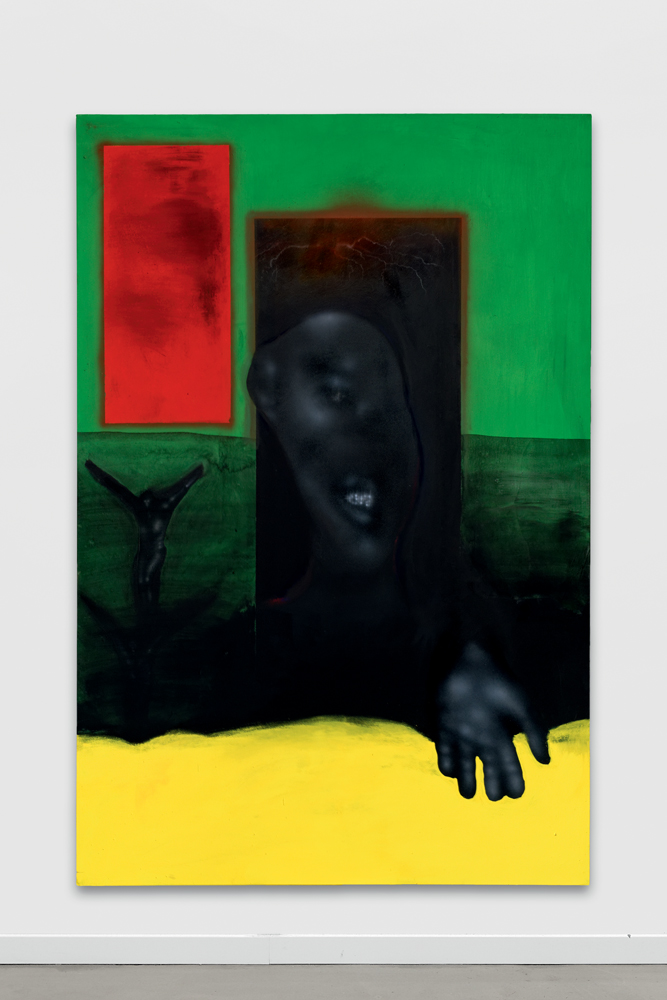

In his series Opéra I and II, Pol Taburet celebrates the occult with silent dramaturgies that mix the symbolic language of European painting with imagery from American rap, contemporary subcultures and quimbois (an Afro-Creole belief system).

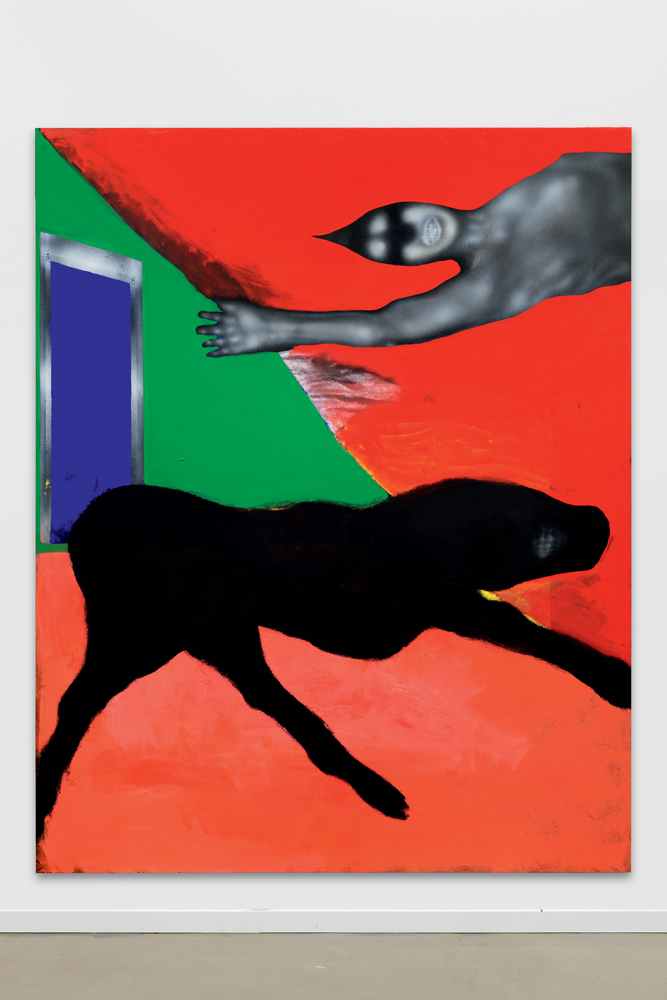

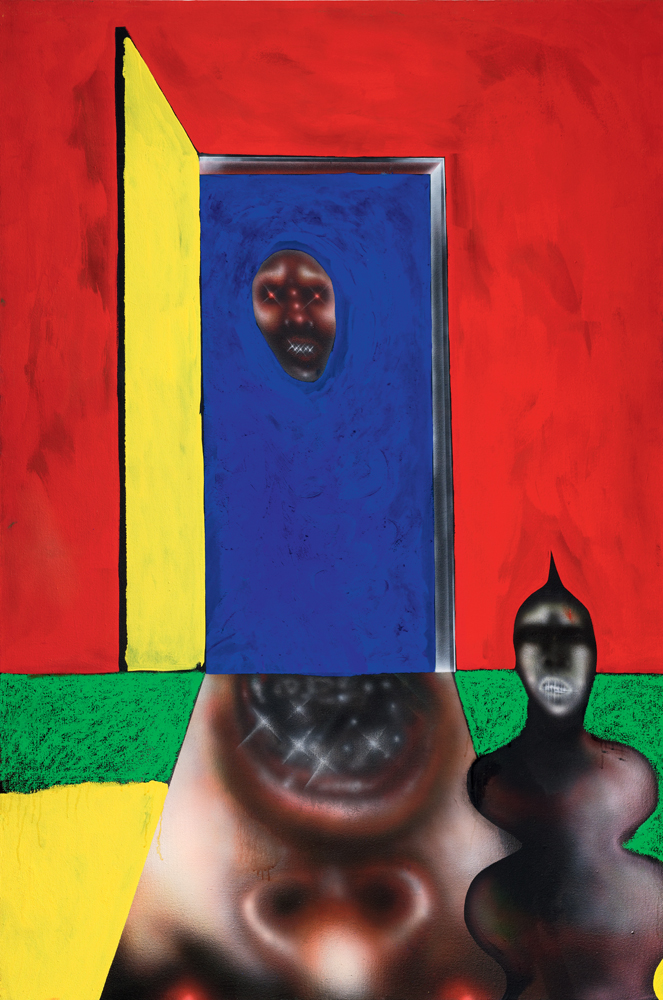

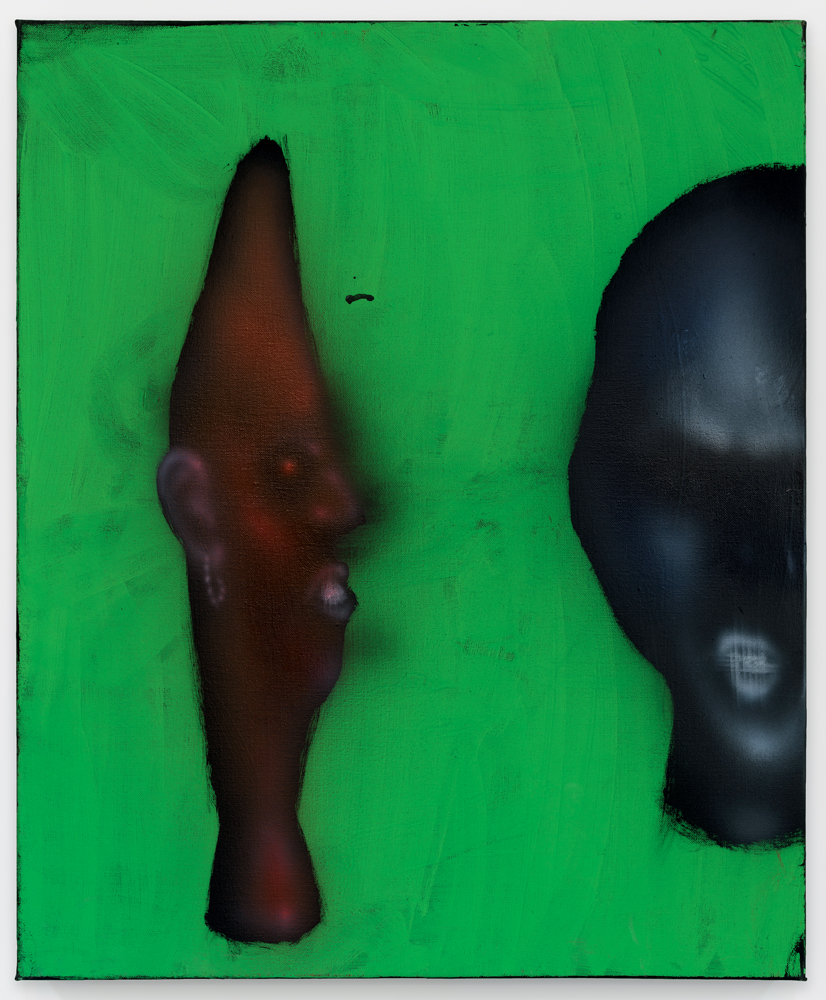

A postcard-style Caribbean sunset is set against an abyssal black background from which mutant creatures, half-human, half-animal, spring forth, at once terrifying and seductive. These bewitching phosphorescent beings seem to emerge from the painting as they emerged for the painter, for rather than the demiurge composer of this strange opera, Taburet is the faithful witness to spectres and visions that chose to appear to him. This is the essence of Taburet’s work: giving substance to these fanciful hallucinations, leading the eye toward a different mental ground and, as in opera, recounting the tragedy of the human condition.

These strange, fictional, fleshless figures with sparkling eyes and jewels often resemble furies. And while we can easily liken them to the creatures in Goya’s Caprichos or to Bacon’s Erinyes (avenging goddesses who pursue the guilty), Taburet’s figures invest the canvas with a certain magic. They break with traditional representations of demonic women as harpies with wild hair and gaping mouths that emit silent cries. Here, the furies appear in radiant glory, illuminating the canvas with an aura of magic and deep spirituality. Though their bodies are subtle exhalations, their soft, reassuring presence feels very real.

For this series, Taburet draws on Caribbean mythology, calling into play a cast of characters that includes soucouy- ants, ceiba trees, will-o’-the-wisps, zombies and dorlis. In Creole tradition the soucouyant – a (usually female) witch – makes a pact with the devil and removes her skin before turning into a huge black bird or fireball that can be seen looming in the sky at nightfall. Creole literature is steeped in references to the soucouyants, as in the numerous books by Simone Schwarz-Bart, a figurehead of Guadeloupian feminist writing, in which Antillais mythology looms large. Women are important here, since they play a key role in the incarnation and passing on of Creole mythology. Taburet’s canvas Spitfire is a striking example, first and foremost because it depicts a fire-breathing soucouyant, but also because the artist sees in it a portrait of his mother. Without her, these family tales would not have been passed down, she who in turn becomes the pictorial starting point for his creatures. One might even see Taburet’s paintings as a series of family portraits, so intrinsically are they linked to the legends of his childhood.

Dorlis are supernatural creatures found in the quimbois legends of Martinique, spirits that enter homes at night and force women (and sometimes men) to have sex with them as they sleep. Historically, the incubus theme was widely explored in European painting: from Dirk Bouts’s The Fall of the Damned (c.1470) to Johann Heinrich Füssli’s The Nightmare (1781), Western art has constantly endeavored to represent the unfulfilled desire of the sleeping woman. But Taburet reverses the perspective and the values: it is no longer women enslaved by demons who are represented but the demon itself, who often takes the appearance of a woman (in works such as Amort, Walk and Par Passion). In reality, the spiritual beliefs of Caribbean quimbois are intrinsically linked to slavery, when slaves were denied control over both their sexuality and their posterity. The Black woman is stripped of her intimacy and her sexuality, her desire is banished. It is in this context of domination marked by castration, rape, impotence and repression that the legend of the dorlis, these demonic sexual predators, came into being. The ceiba tree can also be traced back to slavery: it was to these trees that slaves were tied as punish- ment (Taburet evokes them in his painting Fromager, since they’re known in French as “cheese trees” because their wood was used to make boxes to store cheese).

But Taburet’s work does not only explore this cultural heritage, since he also references American rap and under- ground culture, creating idiosyncratic and surreal worlds where tooth grillz become starry skies (Coucher de soleil II, 2021).

His work is marked by a radical and powerful aesthetic where the pleasure of painting prevails. The vaporous, labile effect of the bodies is achieved through practised mastery of airbrushing, which contrasts sharply with the grainy surfaces of his brightly coloured backgrounds. Thanks to his dexterity in exploring pictorial techniques, his canvases are as poignant as they are elegant.

Breaking with any form of realism, bodies levitate in the void, wrapped in shrouds, or inhabit closed austere worlds, anxiety-provoking and artificial. Here, space seems merely to be a pretext for portraying a place of anguish and oppression: lines channel the bodies, constraining them or pushing them out. The setting is dimly-lit, dismal, enigmatic and disturbing. Welcome to Opéra II – House Party.

It is difficult not to draw a parallel between this series of paintings and our recent experience of isolation during the coronavirus pandemic. House Party resonates with an entire generation who, their bodies confined for months in enclosed spaces, dreamed longingly of sweaty, collective jubilation. On a table in Taburet’s studio lies an illuminated copy of Boccaccio’s Decameron, a collection of tales told by ten young people during ten days of quarantine at the time of a plague outbreak in 14th-century Tuscany. Boccaccio uses the device to tell the story of these youths isolating in the countryside, living in the bubble of an ideal world where “life is a permanent party” at which it is “forbidden to talk about death or illness.”

While the Decameron may resonate with our own recent experience of quarantine, it was the illuminations that caught Taburet’s interest. Indeed, his work is greatly inspired by these learned quattrocento compositions: bodies floating in confined spaces and large, flat areas of bright reds and greens. Like in Taburet’s works, everything in latemedieval Italian illuminations works together to draw the eye into the scene: the absence of background deprives the figures of any historical or contextual anchorage, thus accentuating their ghostly, timeless nature. Space is endless and oppressive.

Doorways often loom large, openings to another world. Behind these doors, figures seem to appear all of a sudden, out of nowhere. And yet, at the same time, we sense that they have always haunted these places. These doors sometimes become frames around the pictorial space, like the proscenium arch of an opera stage, thereby producing a kind of mise en abyme of the funereal spectacle.

Like a leitmotif running throughout Taburet’s work, we find men with tense faces whose skulls soar up into sharp points. Evoking the costumes of the Ku Klux Klan, these characters reflect the most powerful form of domination. Their sheer abundance makes them a coercive army that, for the painter, serves as a generic symbol of systemic vi- olence. And they are everywhere: in the tiniest corners of rooms, reflected in mirrors, and even in the strip-tease club – the protruding leg of a pole dancer is punctuated by a heel so pointed it seems primed to pierce the hand of anyone who approaches. Time is seemingly suspended in this peaceful drama, as if something had just transpired or is about to happen (Strippers Joint and Percocet, 2021). What Taburet endeavours to represent are dark stories, tales of how humankind acts towards its fellow men. In sinister environments dripping with vice, these universal stories unfold, steeped in suffering. By staging a dramaturgy of anxiety, he invites us to look deep into the nature of our inner selves. This is indeed an opera, one whose silent stories evoke violence experienced or observed – in short, an examination of the human condition.

“Des Corps Libres – Une jeune scène française”, frrom May 5th to 28th at the Acacias Art Center, Paris.

Pol Taburet is represented by the Balice Hertling gallery (Paris) and Clearing (Brussels, New York).