4

4

Formafantasma, the duo that is reinventing design

With the exhibition Metamorphosis, Art in Europe Now, Paris’s Fondation Cartier has put together an exciting panorama of young creators. Numéro art interviewed Simone Ferresin of the design agency Formafantasma, which he founded in Amsterdam 10 years ago with fellow Italian Andrea Trimarchi.

By Andrew Ayers.

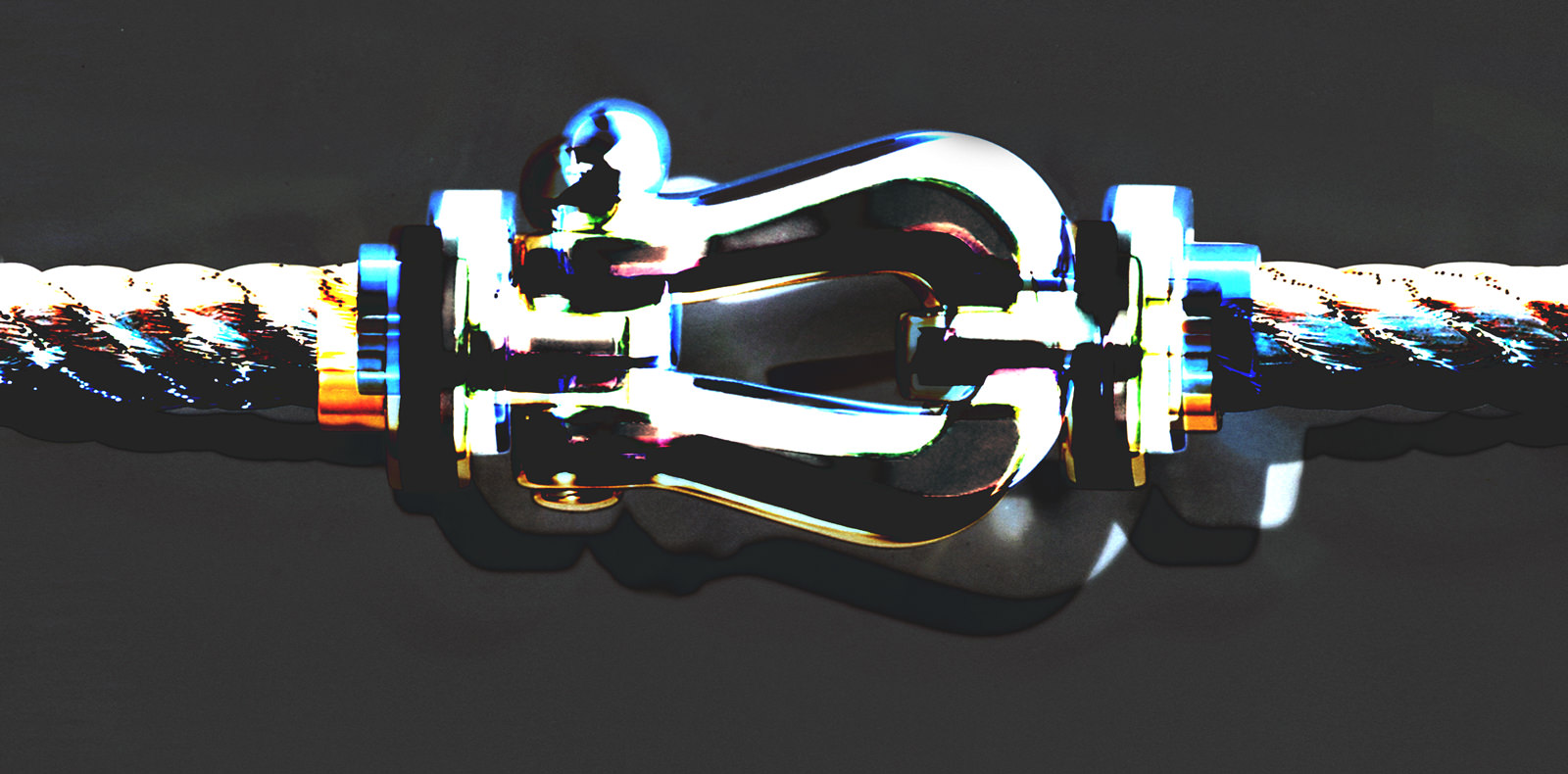

“When you open what’s considered a design magazine these days, what do you see?”, asks Simone Farresin of Amsterdam-based design studio Formafantasma, which he founded ten years ago with fellow Italian Andrea Trimarchi. “It’s usually about a chair, another chair, a lamp, and so on. But the implications of design are so much bigger than that.” We’ve sat down to discuss Formafantasma’s latest project, Ore Streams, which is currently on display at the Triennale in Milan, as part of the exhibition Broken Nature: Design Takes on Human Survival, as well, in slightly reduced form, at the Fondation Cartier. Initially commissioned by Melbourne’s National Gallery of Victoria for its NGV Triennial in 2017, Ore Streams (as shown in its full version) comprises around 15 videos and four pieces of furniture – a table, a chair, a cabinet and a cubicle – that were produced in response to the issue of electronic waste.

“ I think it’s very easy to glamorize dystopia, without even necessarily being aware of it. So we took the completely opposite tack – the objects look very sleek and refined.” Simone Farresin

Questions of the environment, of political- and climate-driven migration and of how to develop strategies to avoid ecological disaster are ubiquitous on the cultural scene these days, but were much less common back in 2009, when Farresin and Trimarchi graduated from the Design Academy Eindhoven. Nonetheless their diploma project, Moulding Tradition, already addressed some of these issues. “We graduated with a piece that was about craft production in Sicily related to medieval migration flows and the influence of Arabs in local culture, connecting that to the present refugee crisis. We joke that had we been around in the 20s we’d have been Modernists. But today, if you’re at all conscious of what’s going on, there are certain issues you simply can’t ignore.” Rather than merely pointing up such issues, however, Ore Streams takes this thinking further by attempting to offer solutions. “We tried to see what design can do to create strategies for making products that are more reparable and recyclable,” continues Farresin. “We talked to recycling companies, law makers, university researchers, NGOs and so on. For instance, take the waste-collection system – in most countries it doesn’t distinguish between functioning and non-functioning equipment, and devices that still work are damaged in the collection process. Then there are the visual detectors used to separate waste: they can’t recognize black objects, meaning, for example, that black electric cables get thrown out with the recyclable copper still inside them. Changing the colour of the cable would be one way to resolve that.”

“In this exhibition, we wanted to blur the boundaries, so that you’re not sure what’s new and what’s recycled, removing the economic-value hierarchies assigned to the new and to waste in capitalist societies.” Simone Farresin

And what about the furniture they designed for the project? Did they attempt to invent a sort of “trash aesthetic”? “In both the videos and the objects, we wanted to avoid the cliché of the discarded and the dystopian,” says Farresin. “When you talk about electronic waste, you often have these dramatic images of open-air dumps in Ghana or Chinese labour dismantling dead equipment. We didn’t want anything that would suggest that kind of imagery, because we felt it leads to narratives of the developed and the under-developed. I think it’s very easy to glamorize dystopia, without even necessarily being aware of it. So we took the completely opposite tack – the objects look very sleek and refined.”

Made, of course, from recycled materials, the four pieces are indeed immaculately crafted, but take a closer look and you’ll soon see something odd about them. The cabinet, in glass, includes the rear casings of desktop computers; the metal table incorporates mobile-phone shells; the cubicle includes the body of a microwave oven; and many details are picked out in gold recovered from circuit boards. “In the context of the exhibition, we imagined these pieces as Trojan horses,” explains Farresin. “You start looking at them and begin to realize there’s a narrative embedded in there which encourages you to engage with the rest of the presentation. But we also wanted to blur the boundaries, so that you’re not sure what’s new and what’s recycled, removing the economic-value hierarchies assigned to the new and to waste in capitalist societies. I’m not sure we necessarily achieved that, but that was our thinking.” But doesn’t all this risk making Formafantasma come across as impossibly po-faced and serious? “Don’t get me wrong, I love pretty chairs, and I can be totally frivolous,” replies Farresin. “Humans are complex. But Andrea and I just think that when you’re a professional, you have far greater responsibility than you do as a private individual.”

Metamorphosis. Art in Europe Now, until June 16. Fondation Cartier.

![Horsphère Bois (III) [1967] de Jean Degottex (provenance : Galerie Jean Fournier, Paris). Huile et grattage sur panneau, 120 x 80,4 cm. En bas : console-table (1902) de Carlo Bugatti. Bois laqué noir, cuir, métal et incrustations d’os, 70 x 116 x 70 cm. Ensemble présenté sur le stand de Sceners Gallery. © Courtesy of Sceners Gallery.](https://numero.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/pad-london.jpg)