1

1

Scott Kahn: how Instagram revealed a 70-year-old painter

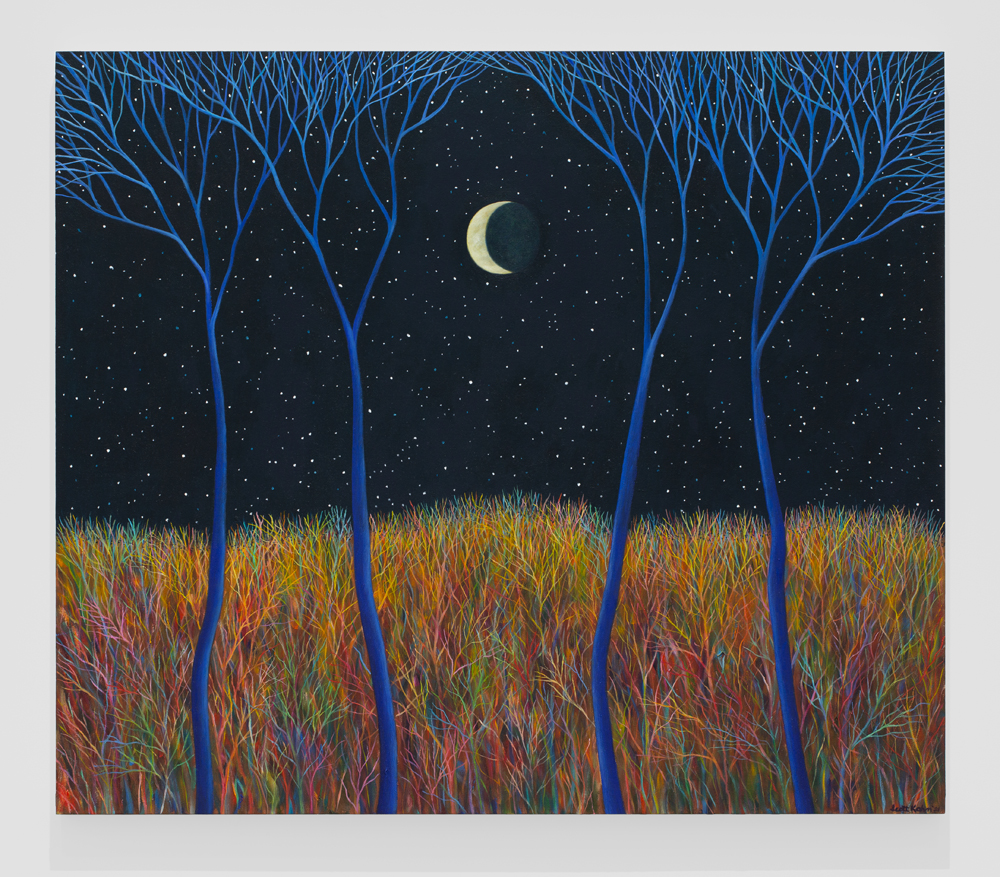

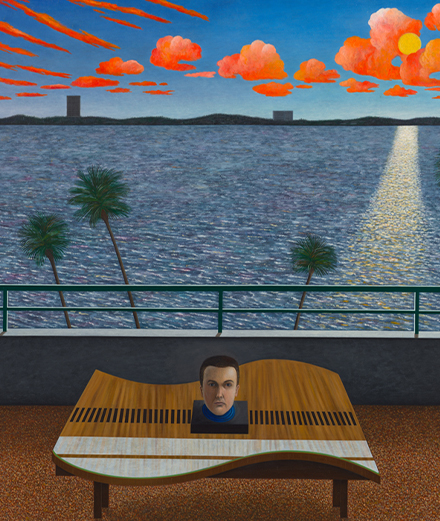

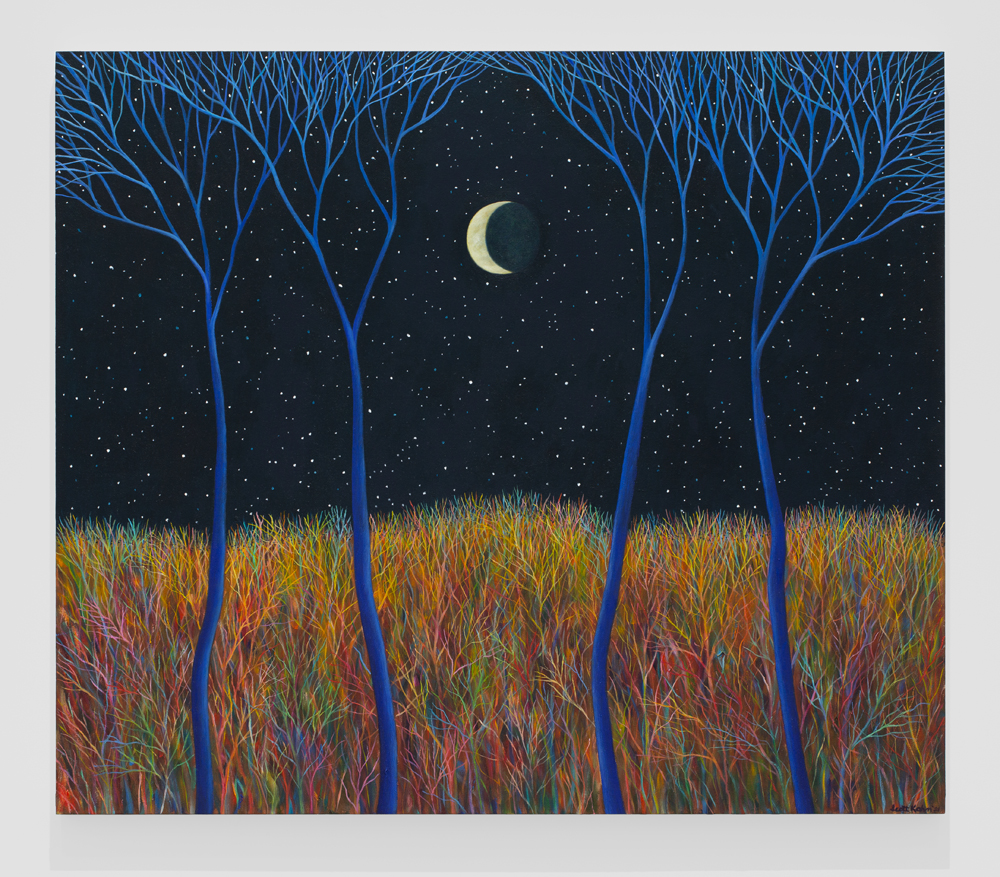

Scott Kahn’s work is defined by the recurring night, taking the form of dreamlike landscapes he paints from memory, mixing the real and the psychological to produce a heightened narration of his life. After decades of being overlooked, the American artist was rediscovered in 2017, thanks to Instagram, at the age of 71 and at the peak of his talent.

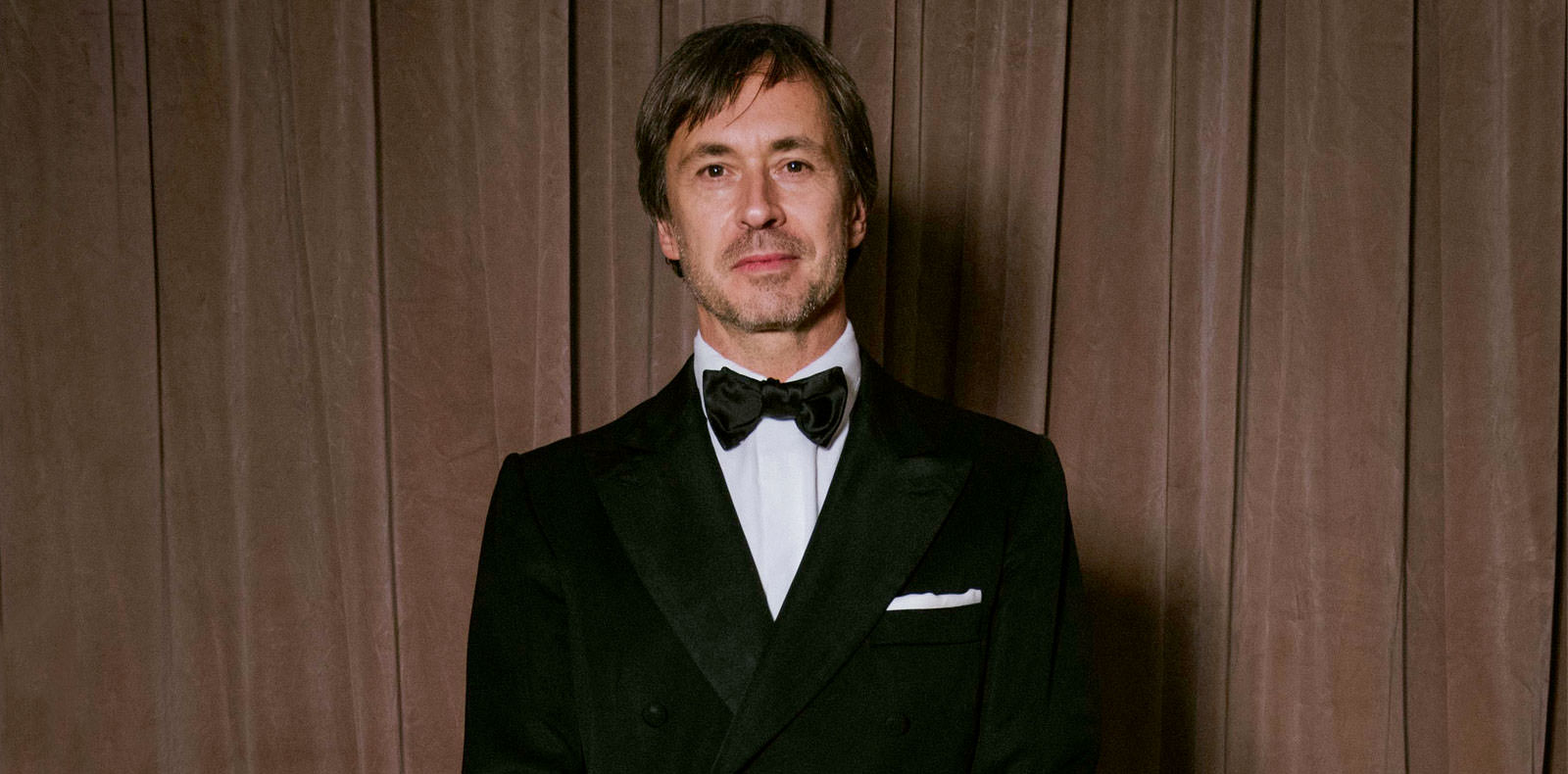

By Éric Troncy.

Scott Kahn: the rediscovery of a painter aged over 70 years old

“It’s just been an amazing journey and very unusual. Because I’m still alive,” recently declared the 76-year-old artist, who is indeed very much alive and whose trajectory has not only been far from conventional but took a spectacular turn in recent years. It’s not such a surprise though, for there is no set model for an artistic career, and critical and commercial success don’t necessarily come in a clear or organized manner, or even at the same time. Scott Kahn knows this well, he who, after almost 40 years of lukewarm critical success and modest earnings (his work sold well but for very low sums), became a star late in life. Overnight, the oeuvre of a whole career came to our attention in its exciting entirety. This kind of phenomenon is becoming more and more common in an age when, thanks to social media, artists suddenly find themselves the darlings of the art world and its capricious market. In Kahn’s case, all it took was for his name to be mentioned by another artist 40 years younger than him.

It’s strange to discover so late in the day the importance of this compact, original and patiently constructed oeuvre – 40 years of painting that suddenly wows us in all its fantasy and its resonance with today’s tastes. Because taste changes, of course, and now we look at things differently. In the 1980s, when it began to crystallize, Kahn’s figurative work had a magic-realism side to it in which the real and the fictional, the everyday and the oneiric, were combined. And although the 80s saw all sorts of painting styles come to the fore (Bad Painting, Neo-Expressionism, Free Figuration, Trans- Avant-Garde, etc.), as the exhibitions of the time demonstrate (e.g. 1981’s A New Spirit in Painting at London’s Royal Academy), magic realism was ignored, and Kahn’s work along with it. “I think the main thing in art is to be uniquely yourself and not to be summed up in categories or movements,” he says, philosophically.

Though he frequented Mark Rothko and the Abstract Expressionists, Khan produced pictures in which hieratic, almost naive figures were set in dreamlike landscapes rendered with all the maniacal detail of a Douanier Rousseau. His work, which also recalled Hockney and Magritte, was apparently not to the taste of the champions of this “return to painting.” Now, 40 years later, at the moment of a another “return to painting” that this time discriminates against no style – and also, probably, in the context of a very healthy art market that is on the lookout for novelty –, his oeuvre abruptly finds itself in the limelight. We should be delighted by this turn in events, for it allows us to encounter an exciting body of work that might otherwise have passed under the radar.

Kahn was born in 1946, in Springfield, Massachusetts, and though he earned his Bachelor of Arts at UPenn and obtained his MFA at Rutgers in the early 1970s, he considers himself an autodidact. “You could say that artists are self-taught to the extent that, whatever education they had, eventually, to find your voice, your unique voice, you have to throw up your education. I think the process for anyone, for any artist of substance, is to throw off the masters, as Alexander Brook said. The main thing I consider to be valuable about going to school, about getting an education of every sort, is that it gives you some technical skills, but ultimately I went through this project more consciously in my 20s: you have to find your unique artistic nature.” On leaving art school, he thought he had found his artistic nature in abstraction. “I wasn’t yet aware of the need I had to have my work reflect my life and the circumstances of my life. I went through a several-year process to learn that.” It finally came to him in the 1980s, under a figurative guise this time, at a point when he began to be convinced that an artist’s oeuvre must be closely linked to their personal life, which they should document in their own way like a sort of private diary. As he explained, “I consider my work to be a visual diary, a record of my life, a reporting of the places and people I encounter. It is not easy to begin a painting, despite the variety and complexity of the world. It is important to me to have a reason to paint, for the impulse to be strong.

“I consider my work a visual diary, a record of my life”.

If I do not feel compelled to work, how can I expect the viewer to respond to what I am reporting? If I am successful, hopefully, the painting will have depth, poetry, and honesty. The effect should be direct and clear. To achieve this result, a creative person calls upon every tool available to him: technical, emotional, intuitive, and intellectual. The act of creating, therefore, teaches us and reveals to us who we are and our relationship to life. This is why I paint.” Kahn’s is not a literal diary though, but rather a poetic one that captures the psychological reality of a particular moment through a landscape, a portrait or an interior. His paintings are done from memory, which leaves the door open to all sorts of strange incursions from his dreams. Is this why Kahn so often paints the night? His oeuvre is full of fantastical nightscapes over which orange moons cast their strange glow… “…Winter grips the landscape, and we watch the moonshadows out the window. No sound troubles the night. No movement breaks the stillness, all is ice and desolation,” wrote his boyfriend, the poet and playwright Frederick Kirwin, who has appeared twice in Kahn’s paintings, once in 1987 and again in 2015.

A late but successful entry into the art market, supported by Almine Rech

“I paint in the master bedroom of an old 1905 house,” says Kahn of his home in New Rochelle in the northern suburbs of New York City. Given New Rochelle’s sea front and 100 hectares of parks and gardens, it’s tempting to see in it the source of many of his pictures, which include seascapes and parks with well-regimented groups of trees. He paints his largest canvases in his Brooklyn studio, and regularly exhibited in New York City – for 25 years he was represented by Katharina Rich Perlow, who put on solo shows for him and sold his work for prices that have nothing to do with his value today. As is so often the case, social media completely changed the pub- lic’s appreciation of his work. A few years ago, on Facebook, he began corresponding with a young painter, Matthew Wong, who in a 2018 inter- view quoted Kahn as one of his influences, alongside Van Gogh, Alex Katz and Yayoi Kusama. Wong later acquired Kahn’s Cul-de-Sac (2017), and posted it on Instagram. “It set off an avalanche of people going over to my feed and people started streaming through my studio door in Dumbo,” recalls Kahn. “Big collectors, galleries, other artists. It was non-stop, and it hasn’t abated to this day.” In July 2021, Almine Rech announced that she was henceforth representing Kahn worldwide, and put on a Kahn exhibition at her Paris space in avenue Matignon barely four months later. Two weeks after the show opened, his canvas Cadman Plaza (2002) went under the hammer at Phillips Hong Kong, pulverizing the $130,000 estimate when it fetched just under $1 million, while on 26 May 2022, at Christie’s Hong Kong, Big House, Homage to America (2012) sold for $1.4 million.

Kahn takes his change in fortune philosophically. “You hope you don’t die in a studio full of paintings. I’m lucky because now they’re out in the world.” He also wonders, with a hint of irony, what will happen to those he sold over the course of his long career. “Many of these collectors are now much older, as I’m older, and maybe they’re downsizing or their children have left their homes and they’re retiring. It wouldn’t surprise me if they auctioned the paintings they bought 20, 30 years ago.”

Scott Kahn is represented by the Almine Rech gallery.