5

5

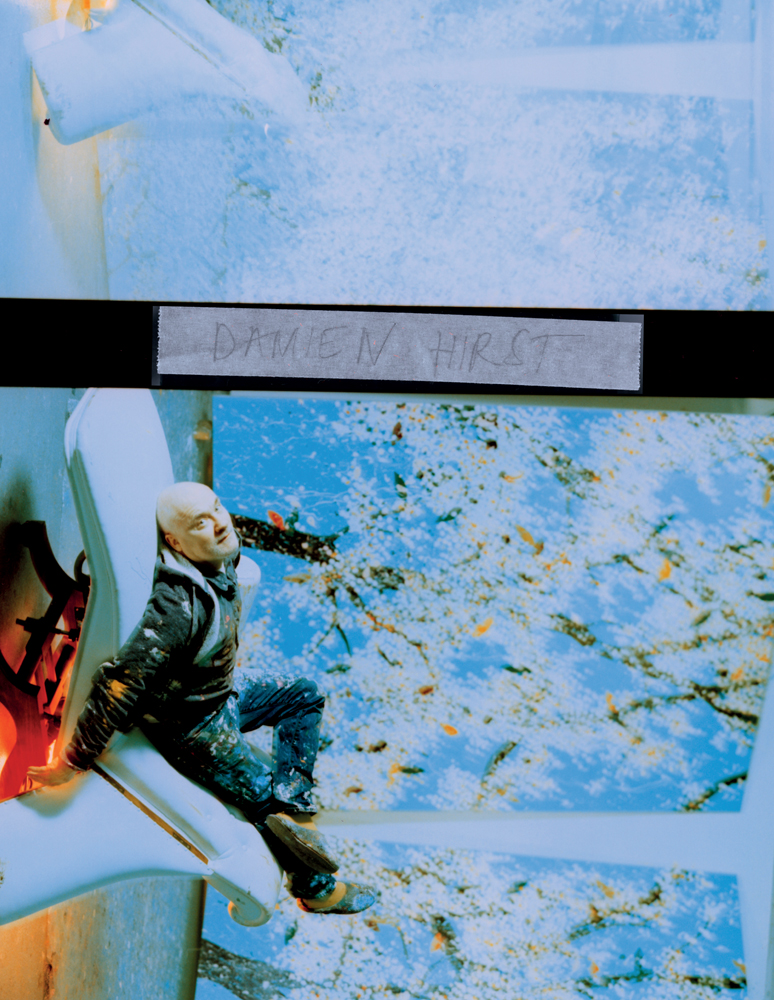

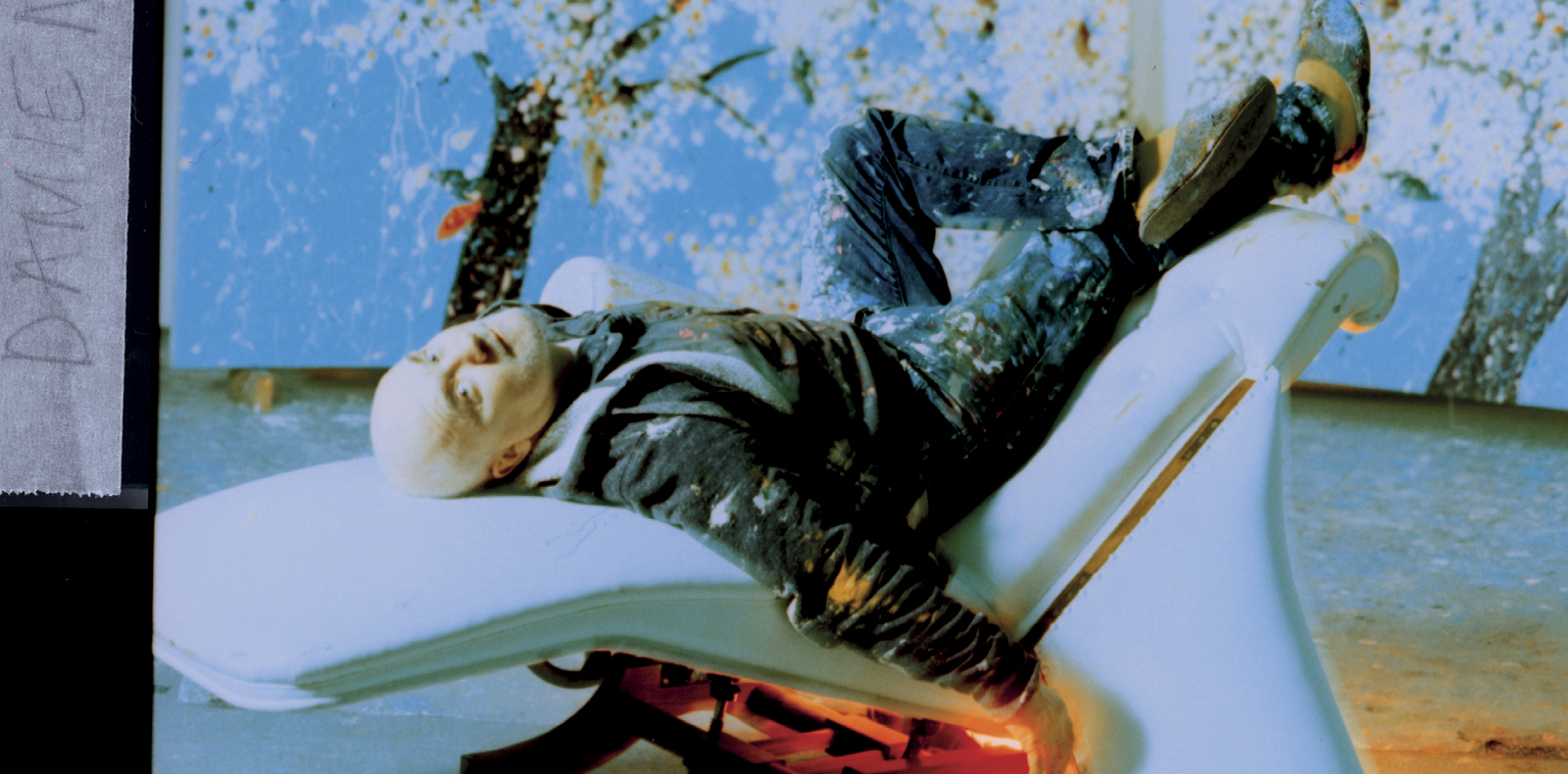

Inside Damien Hirst’s studio, contemporary art superstar currently shown at Fondation Cartier

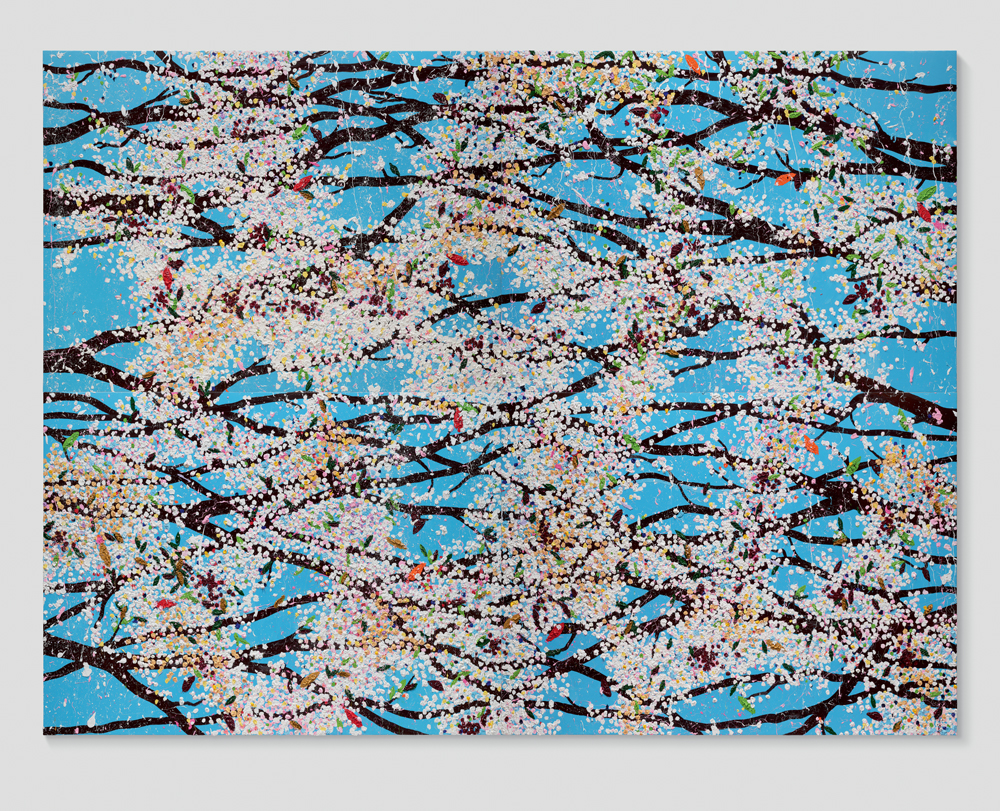

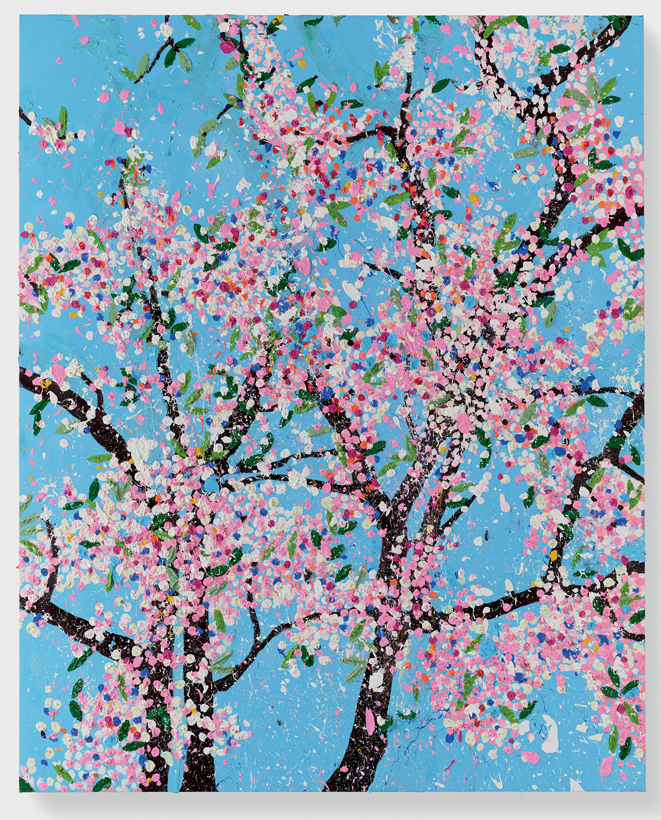

Damien Hirst still has the power to surprise us. His new obsession? Cherry blossom, which he renders as explosions of visceral color splashed across giant canvases, on show at Paris’s Fondation Cartier this summer.

Portraits by Lea Colombo,

Text by Tim Marlow.

Many great artists have suffered from the anxiety of influence, but not Damien Hirst. It’s not arrogance or delusion, nor ignorance of the art of the past – he’s absolutely encyclopaedic on that –, simply that he’s not intimidated by what he calls “the illusion of risk.” Instead, he’s open to looking and learning, and feels an often euphoric sense of connection with everyone from Titian to Sol LeWitt via Bonnard, Bacon and many, many more. It’s why he collects art, and why he’s put so much time and money into building a public gallery in London to show the art of his contemporaries. But it also underpins the way he thinks and works as an artist, which is why his art is always much more than the sum of its ongoing critical hiatus.

Damien Hirst wants his paintings “to be in your face”, but concedes that they’re delicate too.

Hirst is a serial (rather than surreal) artist, and his latest series initially appears as a riot of colour in viscerally applied stabs of paint. But the canvases quickly coalesce, images become clearer and the sense of zooming in and out of focus is energizing and a head-fuck at the same time. The nominal subject is cherry blossom – catnip for art historians like me who need that reassurance of reference. Think van Gogh, for instance, overwhelmed by the fruit-tree blossoms that triggered an unprecedented period of painting after his arrival in Arles in February 1888, which would eventually end with his death back up north in Auvers-sur-Oise barely two years later. Of course, this resonates with Hirst, who also cites a love of the sensuality of Bonnard and the painterliness of de Kooning, whose exhibitions he saw on his first trip to Paris in 1984, even before he went to art school in Leeds. But, more profoundly, he’s working through the contradictions and possibilities of his own art, of earlier series, from Spots and Spins to Visual Candy, Colour Space and most recently his Veil Paintings, which he made a year before beginning the Cherry Blossoms in 2017, and whose gestural swathes of loosely handled dots were the formal entry point to his latest series.

He began the Cherry Blossoms in a studio by the river in Hammersmith in 2017, but moved during lockdown to a much larger space, the airy, top-lit upper floor of a car park in Soho, in the heart of London, that enabled him to finish a total of 107 canvases. He made them alone – no studio assistants or managers, just Hirst and his paints and brushes. I visited twice, once in early spring when the light was dazzling, and a few weeks later when the place was bathed in a soft greyness. Both times, the paintings felt overwhelming, sometimes repelling my attempts to permeate the clusters of coloured dots, other times filling my field of vision and never for once allowing the eye to settle. Damien tells me that he wants them “to be in your face”, but concedes that they’re delicate too. I ask about his susceptibility to the changing light when he’s painting. “I don’t notice it at all. I’m not really into light. I find that paintings are a sort of journey through time. If it takes months or years, you’re painting in so many different lights, all of which help make the work what it eventually becomes.”

They range in size from 2 to 6 metres high, and comprise anything between single panels up to assemblages of six, but they remain intimate because of the mass of distinctly discernible small-scale brushstrokes. The energy and fizz of the surfaces belie the slowness of their creation. Of course, the painting process was frenetic at times – he’s spoken of “diving in and blitzing them” –, but there’s another, equally crucial aspect, one of distancing and contemplation. “Half the time is looking,” Hirst explains. “I sit in front of them and then begin to change the things that annoy me until nothing annoys me anymore.”

I’ve always been fascinated by the inherent paradox of Hirst’s art and reputation: his desire to give minimalism maximum emotional impact; his refusal to play by the rules; his compulsion to take on the art market and play with it; his odd reputation for cynical exploitation but his actual lack of cynicism about art itself in an art world full of jaded knowingness. Once, after a long evening sat next to him at a dinner, he suddenly paused, looked up at me and declared, “The truth is I fucking love art, I actually do,” and cracked up laughing. I laughed too, but believed him then and still believe him now. Art is an affirmation of being alive to him, as well as the means through which he explores an ongoing obsession with mortality. Think back to the title of what is probably still his most celebrated work by far, realized exactly three decades ago, the 1991 tiger shark suspended in formaldehyde that he named The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living.

Mortality and transience, the fleeting beauty of life, the fragility and resilience of nature – these are all consistent themes running through Hirst’s work, confronted in very different ways, for sure, but always there. So although I’m taken completely aback by the scale and impact of the Cherry Blossoms – a forest of pink and blue canvases defining the studio space in London, and which will redefine Jean Nouvel’s beautiful galleries at the Fondation Cartier in Paris – they make total sense. Of course, Hirst talks about universal themes and of Japan and the Sakura, of “the optimistic and the sad … of renewal and death” as we stand in front of the work, but he’s deeply personal too. “I remember when I was about four or five, my mum did this cherry-blossom painting. I was fascinated by it mainly because it was done in oil paint and she’d never let me near her oil paints because they were too messy and impossible to clean up.”

Years later Hirst is wrestling with new work, worrying that, as he puts it, “paintings of trees could be crap,” thinking about the ongoing dynamic between abstraction and representation and “how to bridge those two worlds,” and then he remembered his mother and thought, “I should just do cherry blossoms.” Cherry blossoms are a cultural cliché as well as a powerful trope in art, and Hirst is happy to admit that he’s confronting this head on, with – I would suggest – critical understanding and humour. “The only way to get away with these kind of ‘pop’ paintings as though by Bonnard or Seurat is to enlarge them to this scale… and once they’re at this scale it does also seem funny and ironic too.”

We end our conversation talking about love. “I’ve had a romance with painting all my life, even if I avoided it,” he said recently, and he has described the Cherry Blossoms as being “like Jackson Pollock twisted by love.” But what, I ask, about these paintings as the expression of his own state of mind or of his emotional being as reflected in his work? “Somebody came into the studio recently and looked at the paintings and said ‘Are you in love?’ And I was like, ‘I hope they’re a little bit more fucking aggressive than that!’” I laugh, as does he, but then I catch his eye and he stops, deadpan, and says, “But yeah, I am in love, so maybe that too…” Damien Hirst, the reborn Romantic, acutely self-aware and with a sharp sense of irony? It was ever thus, you just have to look properly.