6

6

How Rashid Johnson broke through as an immense artist while his works summoned African-American history and identities

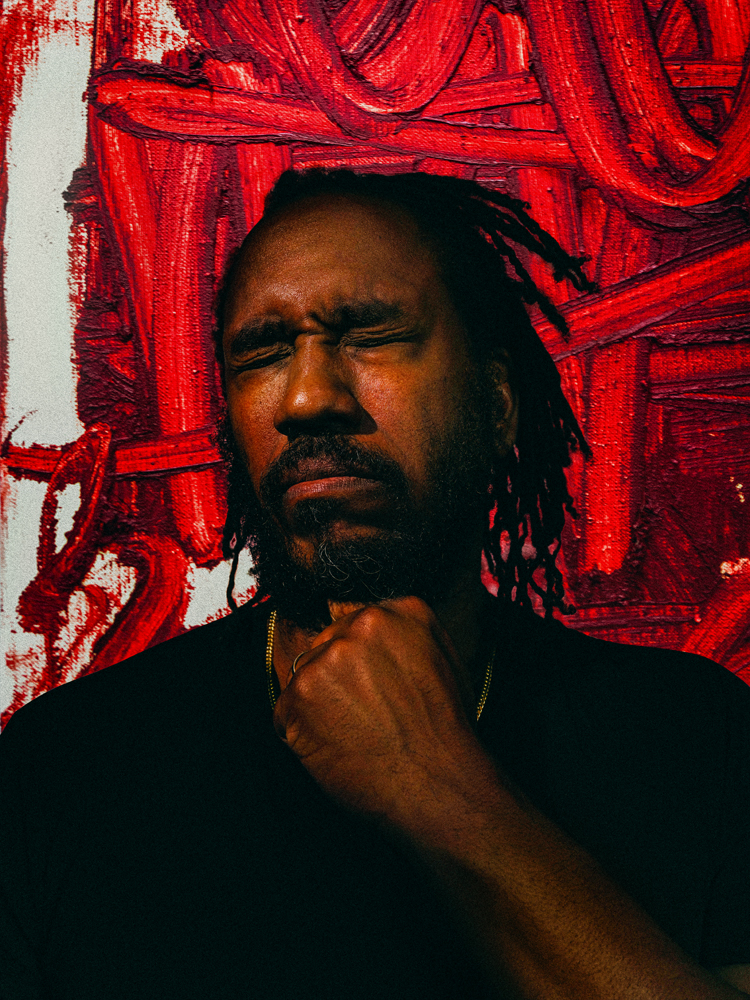

During the 2000s, Rashid Johnson broke through as an immense artist while his works summoned African-American history and identities, their fights, their culture… Numéro art met with this very committed figure of the art world, WHO recently created ties with France by agreeing to act as the very first mentor in the Reiffers Art Initiatives mentorship programme.

Text and interview by Thibaut Wychowanok,

Portraits by Dana Scruggs.

Rashid Johnson wasn’t much more than 25 years old when, in the early 2000s, he conquered his unique position in the American art world. Long before Black Lives Matter, his photographs – one of the most famous, from 2005, shows him posing naked in front of the camera –, paintings and installations summoned up complex narrative systems on the theme of African-American identity and history, its rebellions, its art, literature, music and everyday objects. Even the shea butter used during his childhood by family members became an emblematic material. But his works are neither demonstrative nor outrageously figurative or didactic; on the contrary, they are often more like abstract, some- times minimalist puzzles in which materials, figures and objects (when recognisable) work together to express intimate emotional states rather than simply “representing” the African-American community. In his paintings, there’s a certain vandalism, in the way he creates and destroys with the same movement, burning, breaking, assembling and disassembling materials and forms. Joy and excitement, but also struggle and violence, trauma and healing explode throughout his oeuvre. Nothing is pure in these brain-like works, where thoughts and emotions intertwine.

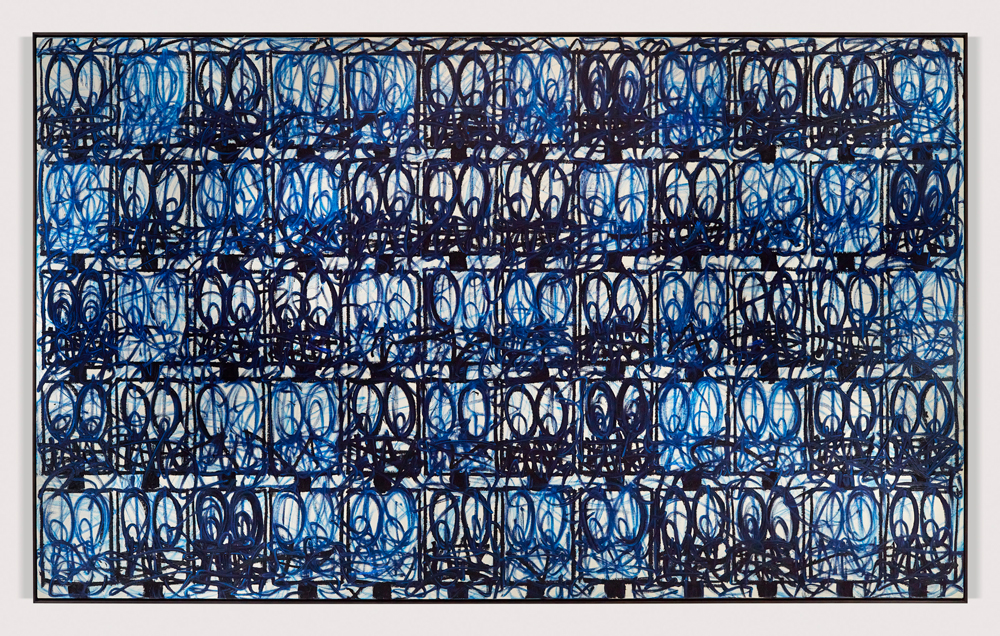

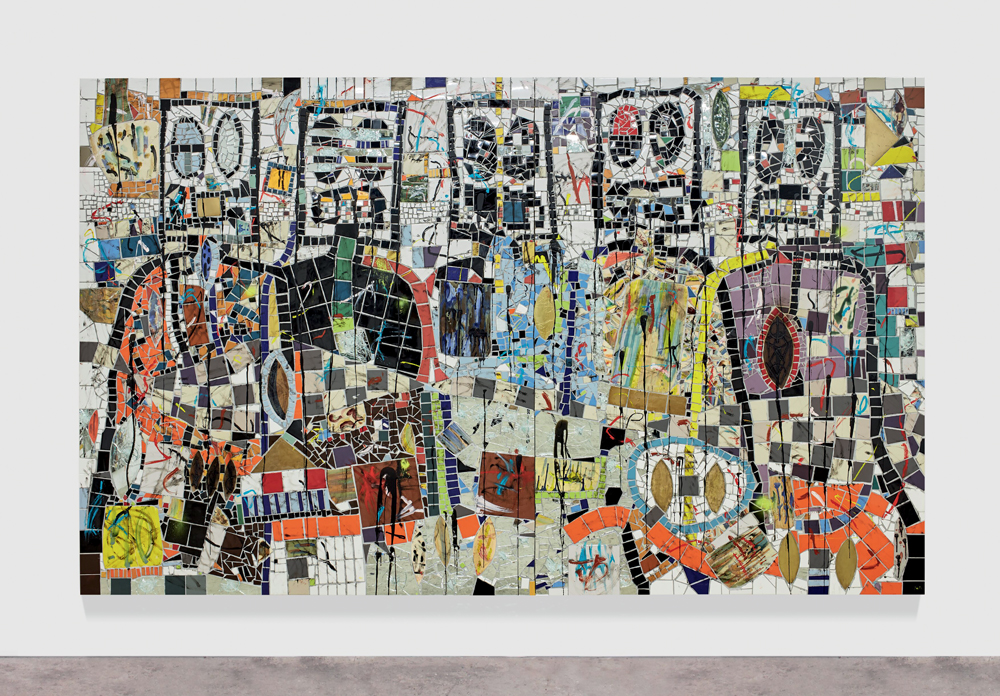

Over the last decade, Johnson has developed two new and already emblematic series. His Anxious Men – black faces scribbled onto the canvas – are multiplied in vast formats, following a grid pattern (an organizing principle he is particularly fond of) that takes on different shades of red, blue, etc. Because the primary idea is not to represent black bodies, but rather the anxiety and questioning of an entire society, independent of skin colour. His characters look at you, crowds of them, in community, and become the accusatory or questioning witnesses of your own existence as a spectator. “Gender and skin colour have never been the main characteristics of these figures,” Johnson insists. His Broken Men series continues the exploration of emotional states in large-format works made using tiny pieces of ceramic. Broken or mended? The material ambiguity echoes the emotional uncertainty.

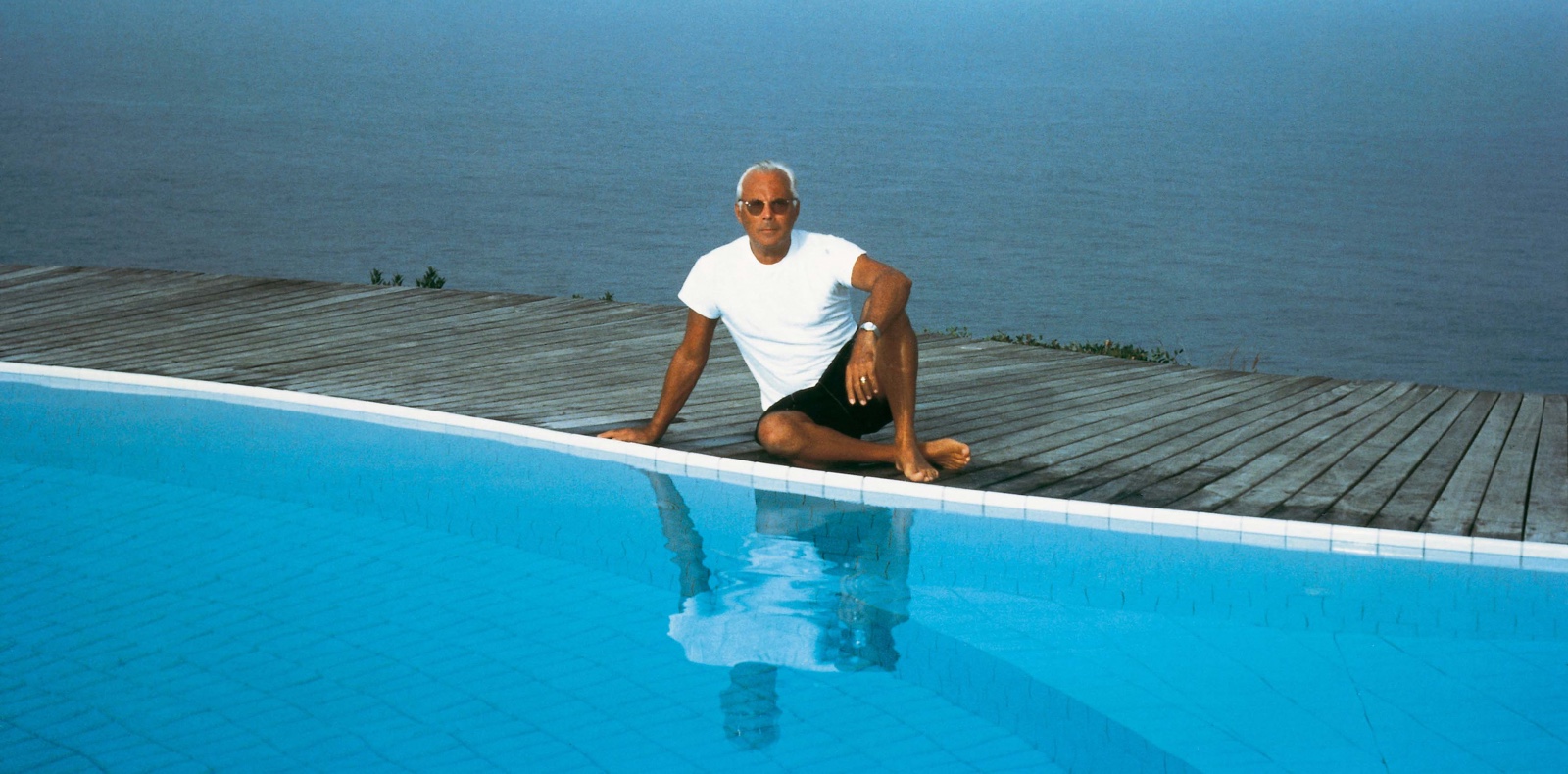

Johnson is pursuing his politically active approach through his engagement with institutions such as the Guggenheim, of which he is a board member, or the Performa Institute. In 2021, he agreed to take part in a French initiative: Reiffers Art Initiatives is a new endowment fund, established by Paul-Emmanuel Reiffers [the publisher of Numéro art], that seeks to promote young artists on the French scene, helping them achieve global recognition, and, above all, encouraging greater cultural diversity. Johnson immediately agreed to be the first international artist to take on the role of mentor for the fund. For several months he has been working along- side young Frenchman Kenny Dunkan, who was selected by Johnson himself from a list proposed by a committee comprising figures such as Emma Lavigne, Simon Njami, Diana Campbell Betancourt, Marie-Cécile Zinsou and the author of this text. At the end of the mentorship, Dunkan will put on an exhibition during FIAC at the Studio des Acacias: produced by Reiffers Art Initiatives, the show will then travel to China and, hopefully, to the US. “Generosity” is a word that Johnson’s often uses, for example with respect to his recent MoMA project, where he installed an open mic for everyone to express themselves and amplify their voices, and also with respect to this first Reiffers Art Initiatives mentorship. It is to this generosity that we pay tribute here.

Numéro art: Your installation Stage at New York’s MoMa this autumn allows visitors to take the mic and broadcast their message within the museum. What were you trying to achieve here?

Rashid Johnson: I thought a lot about the amplification of voices and the opportunity to make oneself heard by a larger audience. My initial reference point for Stage was hip-hop, which has had this really interesting and complicated relationship with the amplification of the voice. There are often references to the microphone, especially in the early stages of hip-hop, the microphone being the instrument used by the master of ceremonies, the MC. There’s a song Microphone Fiend by Eric B. and Rakim where the MC, Rakim, tries to get on stage and they won’t let him use the mic, and he says: “Cool, ’cause I don’t get upset. I kick a hole in the speaker, pull the plug, then I jet.” There’s an obsession with the mic. And when you think about it, activists have long used the microphone and amplification systems to march on Washington. The megaphone is an activist tool to organize. In Stage there’s a mic that is quite low so you have to stay on your knees – it’s also about how much effort you would make to have your voice amplified. It’s about humbling oneself. Children can use them. Adults can use them. There’s a potential audience you have to negotiate with. It deals with generosity too: with this piece, I take myself out of the conversation. And I don’t programme the space. It’s a gift. There’s an artist I was interested in when I was young, Carl Andre. He made these metal plates you could walk on. When I was a young art student, we’d go to the museum in Chicago and play on them. And I love that he gave us these artistic play spaces.

“One of the great debates in my life as an artist is how to satisfy the concerns I have as a Black American male, and speak to the conditions of that experience while not being held hostage by it.”

You recently showed new works from your Anxious Men series at David Kordansky in Los Angeles. I remember seeing some of the first pieces from that series at Hauser & Wirth in New York back in 2016 – a multitude of black faces in a white-cube space.

I call those works audiences. When you walk into that space, you become the performer. You have several options in the way you perform for this audience. You can try to sooth this anxious audience, appease this anxious audience, or make clear your position towards this audience. Although the faces were black, I never really thought specifically about race or gender in this work. That said, because I’m a Black protagonist in my own life and career, I often imagine, when constructing a picture, that Black folks are present in it. But my life is not exclusively filled with Black actors. These Anxious Men stand for emotional states: I’m using textures, gestures and marks to illustrate a collective emotional state and a way of thinking. They may not need gender or race. Those are certainly not their driving characteristics. One of the great debates in my life as an artist is how to satisfy the concerns I have as a Black American male, and speak to the conditions of that experience while not being held hostage by it.

One of the works from your Broken Men series has just been installed at the Metropolitan Opera in New York. How did this series begin? In what way is it different to the Anxious Men?

The Anxious Men are made from black soap and wax. They’re very stable. The Broken Men are built with thousands of pieces so as to really and permanently establish this sense of deconstructed self, of brokenness. They are permanently negotiating past scars and traumas. But I feel that they can also be representative of any time in human history. There’s also a kind of optimism, the idea of being reconstructed, the timeless story of destruction and reconstruction, being broken and building yourself up again.

I’d like to talk about a series of installations that have become a sort of signature for you. They mix a grid structure with exotic plants, videos, books and other things, forming a sort of puzzle for the viewer.

In a way that body of work has always lived with me: the books you find inside of it, the films that are screened on its monitors, all the organic materials… Those are all signifiers and tools I have a long engagement with. I was introduced to the books either in my childhood or graduate school, or even beyond. The structure being a grid is of course a democratizing vehicle for how we consume, right? It doesn’t take on a sense of hierarchy. I’ve always thought of these installations as brains, complicated structures that allow signifiers to flourish and expand and be in conversation with other signifiers. Material like, say, shea butter that you use on the body… What would that have to do with a copy of Harold W. Cruse’s The Crises of the Negro Intellectual? Or a copy of an Alcoholics Anonymous book? Or a palm tree? You start to put these things together and give them agency… The more time you give to a work like that the more generous it can become. At first sight you think, “What is this?!” But after giving it space and time, you can find out about the references to the idea of an archive, personal archives from my childhood for instance…

You’re the first mentor in the Reiffers Art Initiatives programme. You supported French artist Kenny Dunkan. What’s your take on his work?

When an artwork starts to give you a sense of how an artist considers himself in the world and takes aesthetic decisions, that’s when I get very turned ont. Kenny really performs for me in that way: it’s visceral, about the body, engagement, conflict and confrontation. There’s real ambiguity in how he uses material and what the intentions are behind his sculptures, the way they can or cannot perform, whether they’re objects for torture, sexual engagement or leisure. They’re very sophisticated, and exciting to discuss as a mentor.

What’s the best advice you can give a young artist?

People often believe they can follow the trail someone else blazed. But we’re all on our own journey, and what makes artists successful is becoming that vision of themselves rather than trying to mimic someone else. I’m not talking about aesthetics, but rather the path or philosophy of another artist. It’s important to pay attention – reading, looking and being curious about the artists you consider your heroes – and then devise a philosophy of making and navigating spaces that really fits with who you are professionally, both in your studio working and in your thinking.

My favourite Dunkan pieces are his “shrouds,” white bath towls he dries himself with, leaving dark traces of melanine on them. Put on display, they become abstract, conceptual paintings.

Absolutely. These works are the ones that impacted me the most. I was lucky enough to be able to acquire one from his New York exhibition. In that sense, I put my money where my mouth is! I’m enthusiastic about living with these works. This seemingly simple and quite poetic gesture is the kind of thing that people often overlook, but it’s precisely what gives you an artist’s authentic vision and thinking, rather than what they do when they’re just trying to impress us. In this work, Kenny is very generous and authentic, he gives us the shading of his body in a way that’s quite naughty and a little dirty. What is the artist’s body in the end?

Rashid Johnson is represented by Hauser & Wirth and David Kordansky Gallery.