15

15

Who is Lisa Lyon, Mapplethorpe’s muse and performance pioneer?

Published on 15 August 2024. Updated on 6 September 2024.

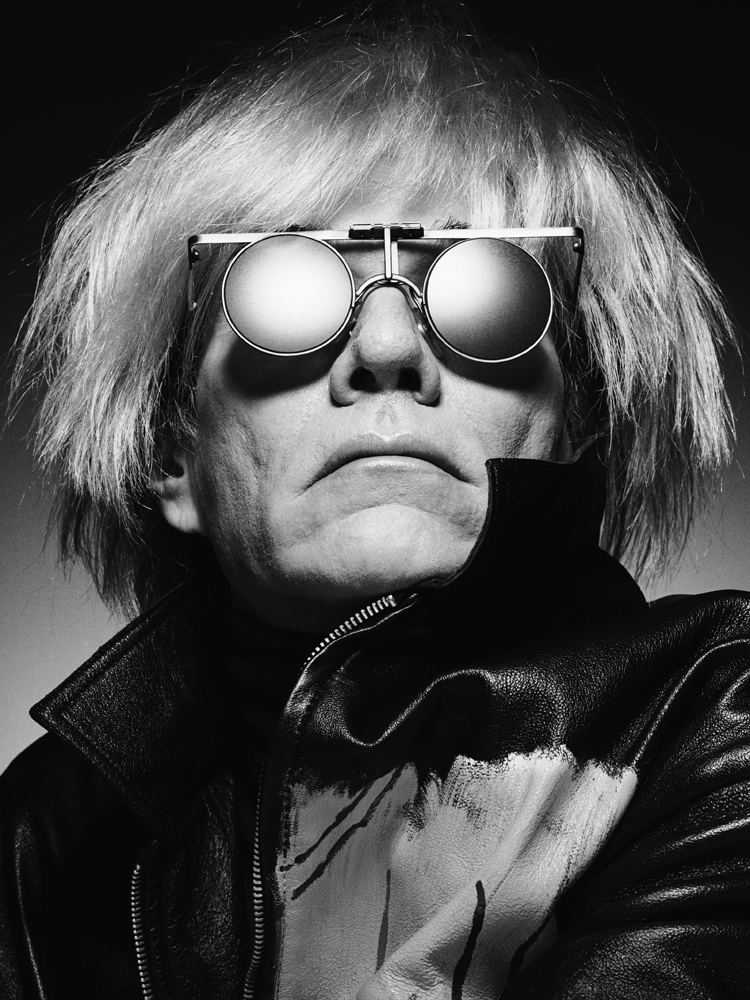

Lisa Lyon, bodybuilder and muse of Helmut Newton and Andy Warhol

She began weight training in 1977, after meeting Arnold Schwarzenegger. A model and actress who posed for Andy Warhol and Helmut Newton (she was one of the four Big Nudes), she patiently built a physique that caught the attention of the American photographer Robert Mapplethorpe, who produced a series of over 200 images of her, as well as inspiring the British sculptor Barry Flanagan. Though she studied art, it was with a view to becoming a medical illustrator. Things turned out rather differently, and Lisa Lyon, the first female bodybuilding champion, invented what was perhaps a strange artform of which her body was the instrument.

Born in 1953, the daughter of a surgeon and an interior decorator, she grew up in Los Angeles. “My childhood was dark. My parents didn’t realize how dark. It was very dark. I never liked horror movies because I was having my own,” she later said about the nightmares that assailed her every night. “I evolved a whole cult of ritual practices to close this stuff out… It had to do with numbers, counting, touching things. I was seeking an equilibrium, getting up at night to perform these rites running around the house three times counterclockwise.”

Yet she trusted the little voice that told her, “When you’re 12, all this will be under control. You just have to tough it out.” After high school, she studied anthropology at the University of California, as well as ballet, flamenco, and jazz dance, before discovering art and kendo, a form of Japanese sabre fencing. At the university’s kendo club, where she was the only female, she experienced something new: “It was the first time I was not being treated as a woman and not being treated as weak.”

“In the 50s you had women like Marilyn Monroe, who were strictly sex objects. In the 60s you had Twiggy, who started the undernourished, androgynous style. In the 70s there was Farrah [Fawcett]. Now, in the 80s … women are building up their bodies without sacrificing beauty or femininity.” – Lisa Lyon (1981)

She nonetheless felt that she didn’t have the physical strength to fight her male opponents, and began weight training, which had been a rather marginal discipline until the release of the 1977 film Pumping Iron, which followed bodybuilders who were preparing for the 1975 Mr Universe and Mr Olympia contests, among them Schwarzenegger.

On 16 June 1979, after seeing an advert, Lyon took part in the world’s first professional female bodybuilding championship, organized by the International Federation of Bodybuilding in Los Angeles. She won the top trophy, becoming the first female champion of a sport that few women practised at the time, two years before Jane Fonda published her Workout Book.

The victory made Lyon a media phenomenon, and Playboy offered her a cover shoot, which she accepted for reasons she later made clear. “The fact is, I didn’t need another photo in Muscle Magazine,” she told The Washington Post in 1981. “The people who read Playboy are the ones that need to be educated to this concept of femininity … In the 50s, you had women like Marilyn Monroe who were strictly sex objects. In the 60s you had Twiggy, who started the un- dernourished, androgynous style. In the 70s there was Farrah [Fawcett]. Now, in the 80s, health is a reality. Women are building up their bodies without sacrificing beauty or femininity. Vogue this month is all about the active body. It’s talking about optimum weight for health – not skinniness. I feel I represent a trend. And this isn’t just some vain, vapid thing I’ve done. This isn’t, ‘Ladies, want to get in shape for the summer?’ – Give me a break!”

Robert Mapplethorme photographed her more than 200 times

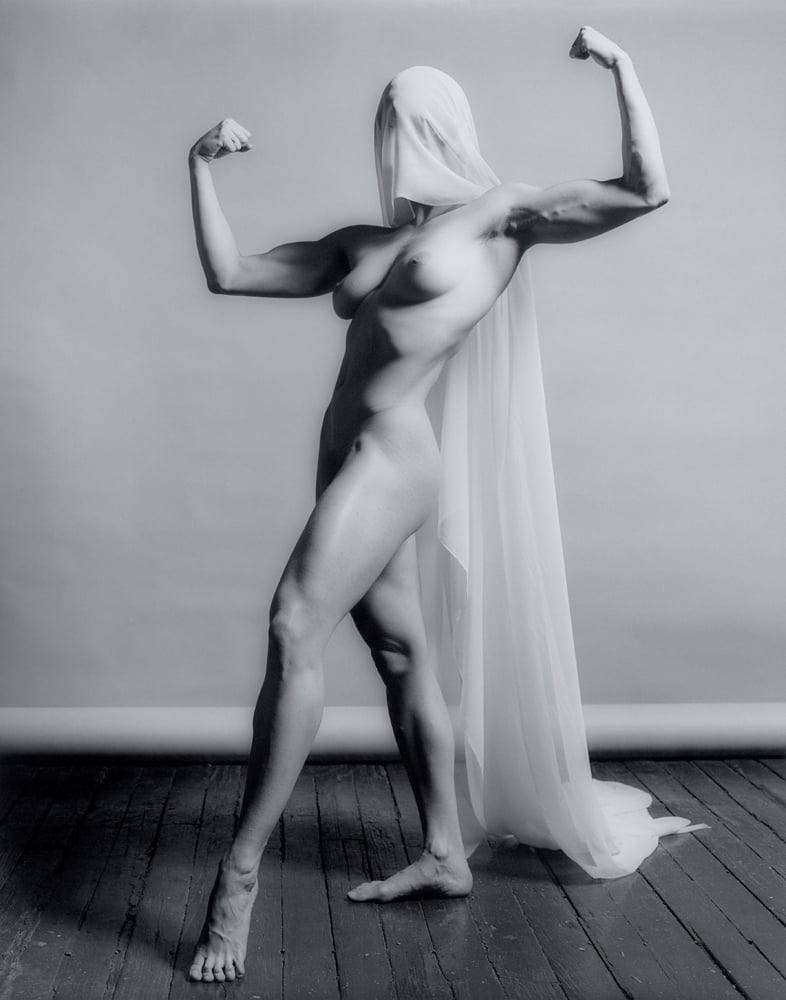

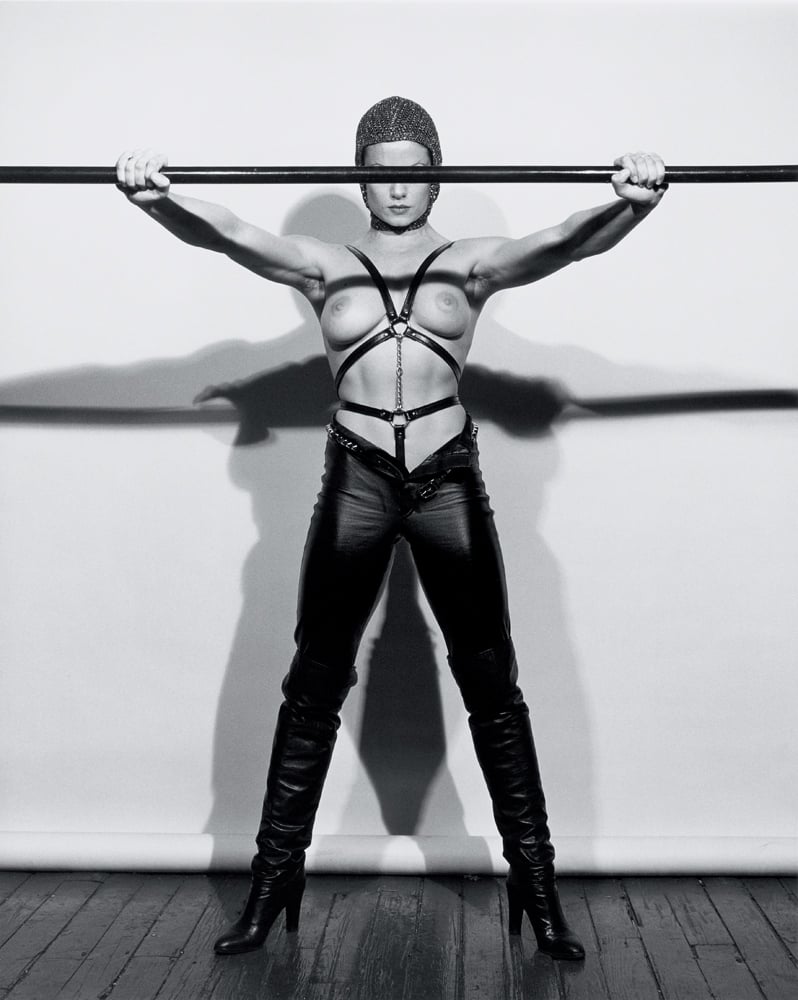

When the International Body-building Federation invited her to take part in the following year’s champion- ship, she declined, declaring that she felt she was less of an athlete and more of a performance artist. Indeed it was shortly after winning the contest that she met Mapplethorpe, at a party in a SoHo loft. The man who had proclaimed that “photographing women is not the experience I am seeking” was fascinated by her body.

Over a period of two years, he took over 200 shots of Lyon, and she became by far his most photographed subject. Six of Mapplethorpe’s Lisa pictures were published in the avant- garde review Artforum in 1980, others were shown at Documenta 7, while a greater number was gathered together in the book Lady Lisa Lyon by Robert Mapplethorpe, which came out at the same time as the exhibition Lady, Photographs of Lisa Lyon at Leo Castelli’s gallery in New York.

“In session after session, Lisa posed as a bride, broad, doll, playgirl, beach girl, bike-girl, gym-girl, and boy-girl; as frog-person, mud-per- son, flamenco dancer, spiritist medium, archetypal huntress, circus artiste, snake woman, society woman, young Christian, and kink,” wrote Bruce Chatwin in the book’s introduction. “The photographer and his model have conspired to tell a story of their overlapping obsessions. Their glorification of the body is an act of will, a defiance of nihilism and abstraction, a story of the Modern Movement in reverse.” In the short text accompanying the Artforum images, Lyon explained, once again, that she defined herself more as a conceptual artist than a bodybuilder. And in 1979, she told WET magazine, “I’d like to be a proponent of social change and a representative of a new artistic standard.”

Lisa Lyon, a pioneer of bodybuilding and performance in the 70s

While Lyon has not – yet – gone down in the annals as an artist, this perhaps surprising declaration resonates with certain approaches to art that have indeed been accepted by posterity. With his 1970 The Act of Drinking Beer with Friends Is the Highest Form of Art, the American artist Tom Marioni made an artwork out of boozing, while the year before Gilbert & George were already declaring themselves “living sculptures.”

In the context of 1970s British and American performance art, Lyon’s claim doesn’t seem so strange after all, and in that light we might take her artistic pretensions seriously. Arguably, certain conventions, sedimented by time, stand in the way. How does Lyon’s participation in Mapplethorpe’s image-making constitute an “artwork”? Her name doesn’t appear among the artists who took part in Documenta 7 because the photographer’s is listed.

But perhaps we should go beyond these old-fashioned understandings. By entering into the spirit of the 1970s, and by observing how today the frontiers between the different arts are ever more blurred, we can accept the premise that Lyon set out the frame- work of an artform without any commercial goal – something that nowadays either frightens or fascinates.

In her recent article about Lyon in the Gagosian Quarterly, Fiona Duncan pushed the argument in precisely this direction, in particular noting that none of her “perfo mances” were ever recorded. “Painter Nancy Reese recalls seeing Lyon perform naked and covered in graphite circa 1979–80 in Venice, California,” writes Duncan. “‘She used sand and stones,’ Reese remembers, ‘like the ones in the Kyoto temple gardens as her stage set. The audience was rapt, mesmerized, as she slowly and powerfully moved around the small stage assuming various archaic poses. It was like seeing some sort of zen version of Nijinsky dancing in Afternoon of a Faun. I can’t recall if there was music or total silence. The performance seems to me now not as an actual event but the memory of a dream.’”

But perhaps we don’t need such evidence to follow Lisa Lyon’s logic. When she died last September, at the age of 70, the French singer Bernard Lavilliers, who was briefly married to her from 1982 to 1983, repeated it once again: “For her, bodybuilding was a form of performance.”