11

11

Who is Alexandre Diop, the young artist mentored by Kehinde Wiley exhibited for the first time in Paris?

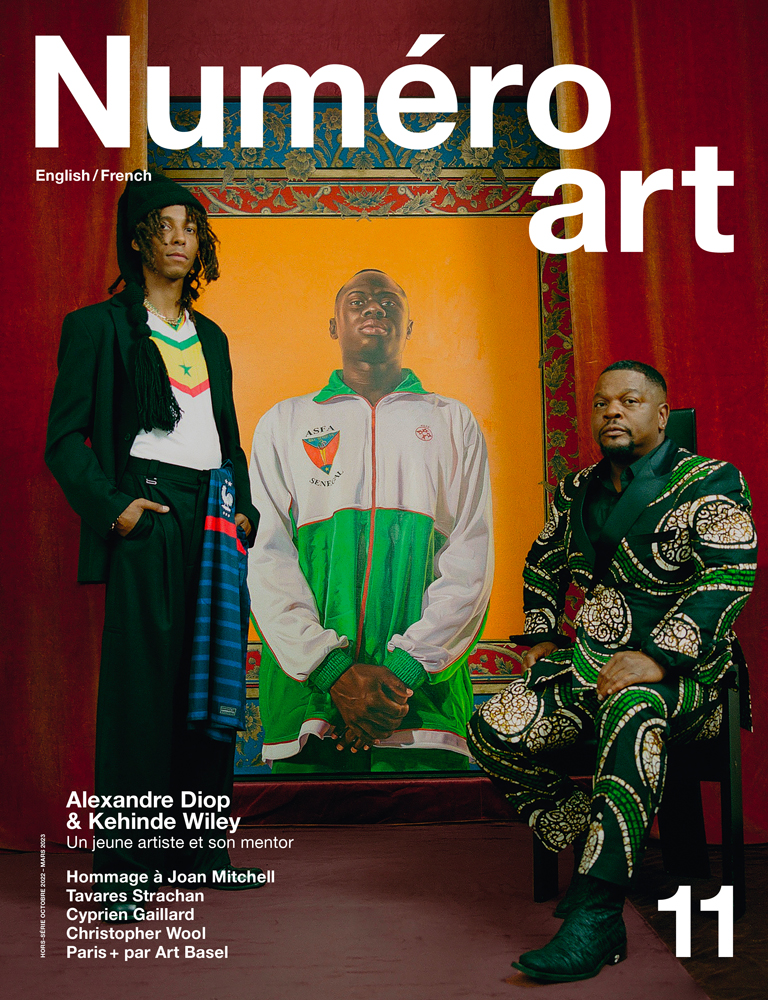

For the second edition of its mentoring programme, Reiffers Art Initiatives has invited the young French artist Alexandre Diop to show his roaring, monumental canvases at the Acacias Art Center starting October 19. This is Diop’s first show in Paris, organized under the aegis of his mentor, contemporary-art star Kehinde Wiley. Together, they appear on the cover of the new Numéro Art, available in newsstands and digitally on October 18.

Interview by Thibaut Wychowanok,

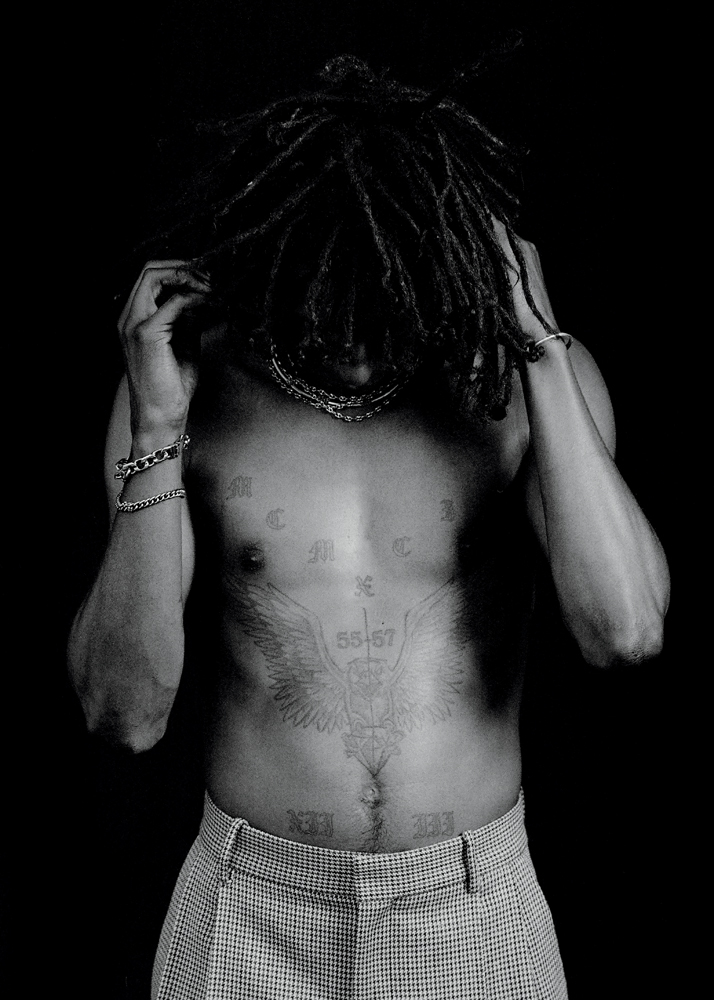

Portraits by Kenny Germé,

Production by Kevin Lanoy.

Find this issue in Numéro art 11, in newsstands and digitally on October 18.

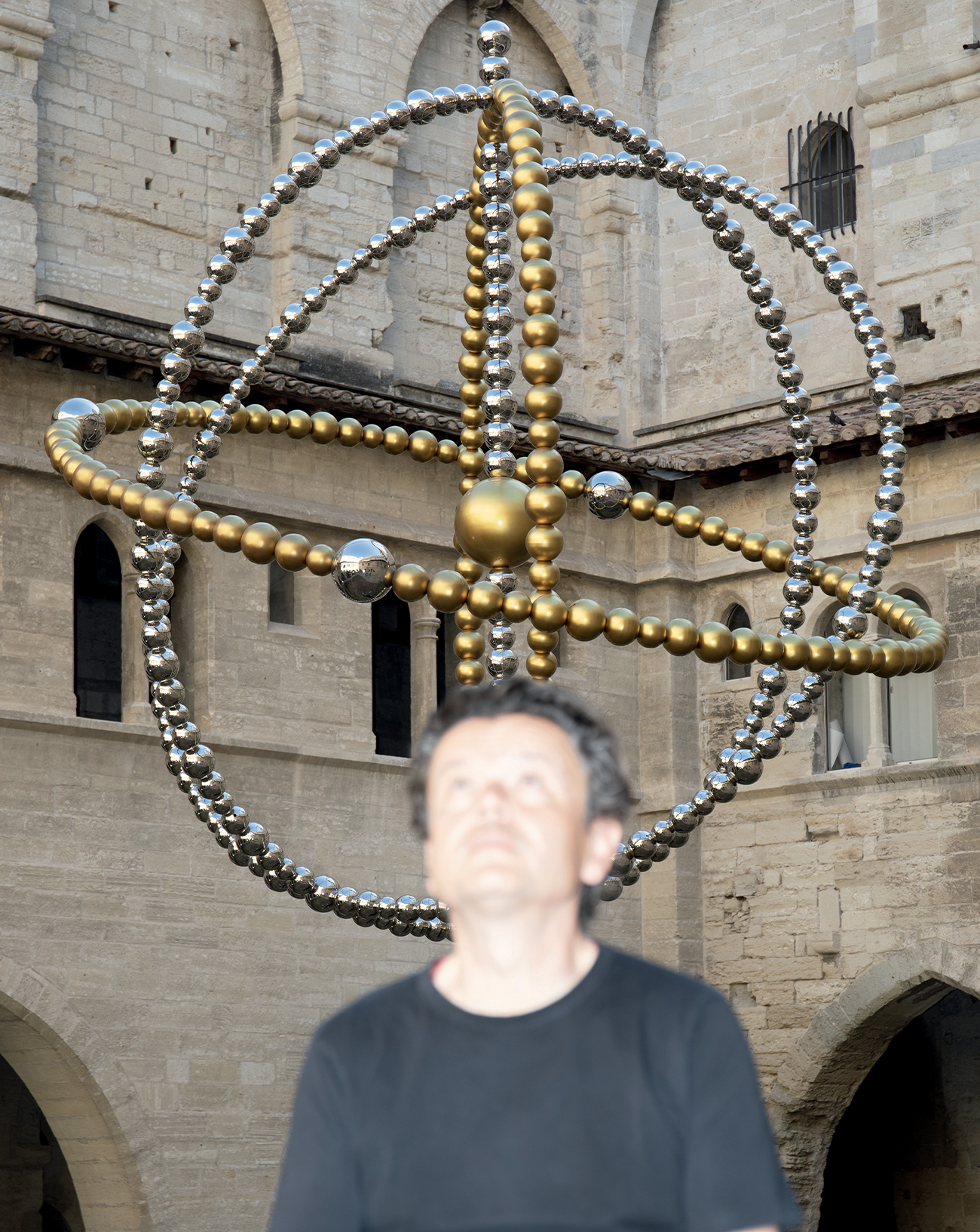

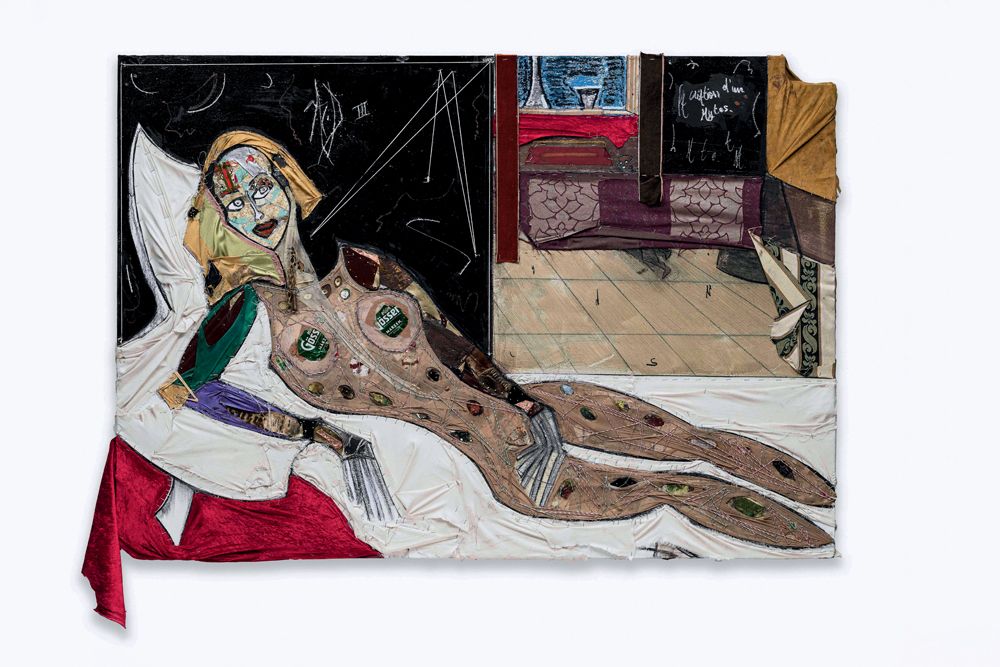

Alexandre Diop talks about “image-objects” when describ- ing his work: his first step in the act of creation is to gather all sorts of discarded objects and materials during long walks through abandonded places near his home. Born in Paris, in 1995, to a Senegalese father, Diop moved to Berlin at the age of 18, and now lives and works in Vienna. In Diop’s eyes, Kehinde Wiley, who is probably best-known for his portrait of Barak Obama, represents a model of Black success. They have in common Dakar, where Wiley founded the residency Black Rock, but also a dialogue with past masters as well as with the contemporary world.

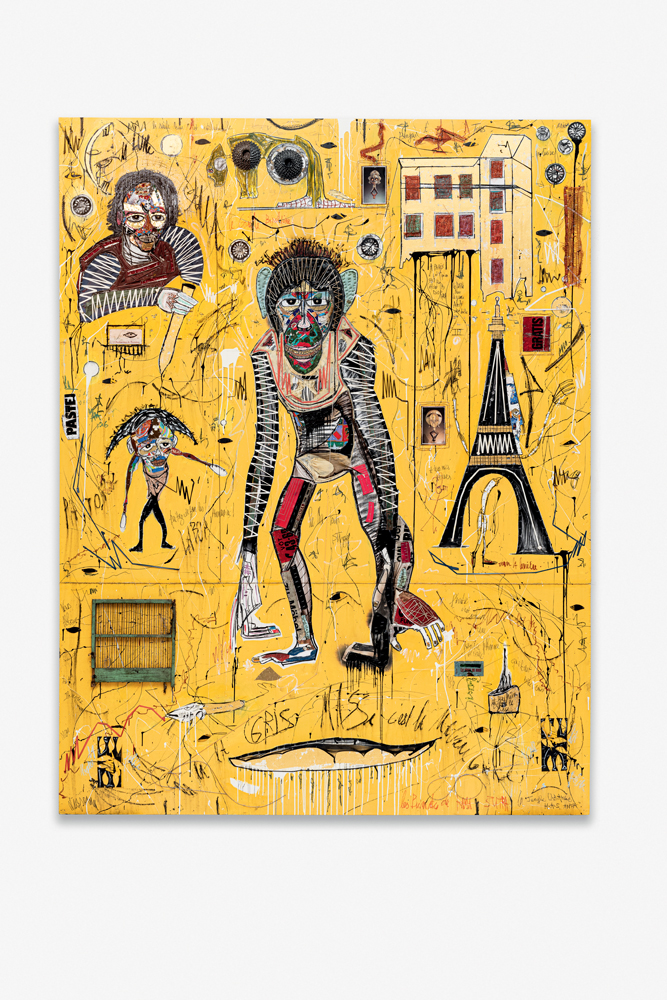

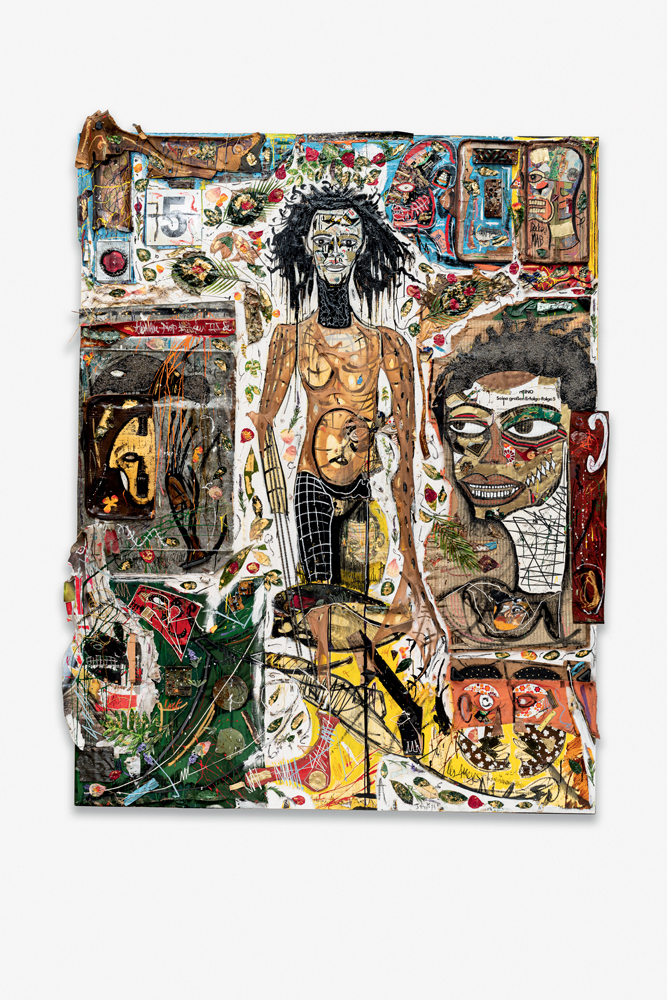

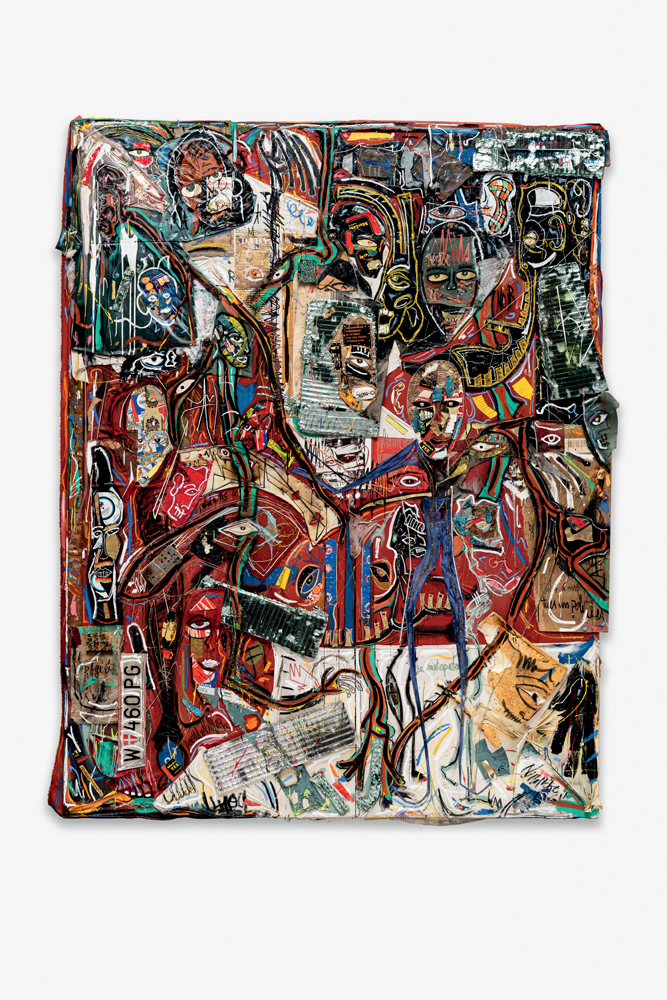

Thibaut Wychowanok: What strikes me about your works is that they’re never just paintings. They’re made up of materials as varied as coins, fabric, metal rods, pages from books… Alexandre Diop: Those objects make up my palette as a painter. They are things I collect and that fill the endless chaos of my studio. I find them in scrap yards, in the street, in warehouses or abandoned houses which I break into like a burglar. This collecting process initially relates to the idea of the forbidden. The objects I’m interested in are under- rated, discarded, damaged, forgotten. Placing them on canvases gives them a different, more potent value. I need to start from reality in order to create a new reality. I found a box of Banania instant-chocolate powder and used it because it reminds me of pervasive racism and how embedded it is in mass commercial logic. The printed word enriches my paintings. The occasional abstract words. The words and photos also come from books lying around the studio. I tear out the pages that interest me. They inspire me or end up in the paintings, like this Dada book cover. Dada was also intent on disrupting the elites and their values. Art can be twisted and used in another way. I like its spontaneous, automatic poetry. The idea that overlapping words is already a creative process.

You also write some of your own words and sentences on the canvases… They are either my own texts – I’m also a musician – or things I’ve heard in rap songs. Writing a sentence on the canvas is like embedding a conviction that I have at a given time. I create when I’m in a state of trance, it’s like a dance. I draw directly onto the canvas without preparatory sketch- es, sometimes with a visual or compositional reference in mind. I take a piece of charcoal and throw myself into it, no holds barred. I grab objects from the studio, mix, tear, cut, burn… I always have a nail in my mouth and a stapler or a hammer in my hands. It’s all about vision. Allowing things to happen and emerge.

“I create when I’m in a state of trance. It’s like a dance.”

The new formats you have produced for your Paris exhibition are sometimes more than 3m high. What does this monumentality represent? Size alters the relationship between the viewer and the work. Paintings cannot be domestic decorative objects. With my earliest pieces, I embraced this monumentality so that the works would acquire an ability to crush. My use of gold derives from the same ambition. I try to endow the pieces with a sacred dimension, to force the viewer to bow down before the compositions. I give them no other options. I know what I want to say, even if everyone is free to interpret them whichever way they want. My works are dangerous. Literally – they can kill you if they collapse on you! They are also dangerous to make. I cut myself. I often bleed when working. The blood ends up on the paintings. I spit on them. The paintings scream.

Are they inhabited by the violence of the world or by your own violence? If I hadn’t become a painter, I would have ended up in jail. Even though I come from a very privileged background. I played football when I was younger, as a defensive midfielder. They called me the pit bull. It’s the violence I feel, I believe. A historical violence. A violence that stems from the young man I am, from the way I arrived on Earth, from the power struggles and inequalities in the world. I feel violated every day. Not violated in a sexual sense, but violated in the respect I should be given. I am a man, I take advantage of the system. But as a young man with an immigrant background, I experience the violence of life. My work expresses this suffering and, more universally, the violence we all experience at birth. The pain of coming to life. The first cry. The first tears.

“I often bleed while working. The blood ends up on the painting. I spit on them. The paintings scream.”

Who are the characters you paint? It can be me. Or people who inspire me like Malcolm X or jazz musicians. They are not necessarily real people. They inhabit a world – a matrix – where they are not constrained by the same social and natural laws. Like an Olympus. They don’t need to wear clothes. They are boneless. Their anat- omy and skeleton are exposed. The people I depict are perhaps from the future, the past or another present.

A monkey takes centre stage in one of your recent paintings. What does it represent? Primates are the most evolved version of man. What we should be. We think we are smart, but look at how we treat the world, what we do to it, the extreme poverty and suf- fering. Have you ever seen gorillas invading South Korea with planes?

In your paintings, we seem to witness a return to a primitive and primary nature, a place before gender, before society… Yes, the Olympus I was telling you about. The people I depict don’t engage in relationships of power or sexuality. They present themselves as they are, their bodies exposed. They have no qualms about showing their suffering, how broken they are by life. They are exceptionally honest. Without ul terior motive. I envision a world in which everyone is respected. My works are always an invitation to make peace, to gather, to talk, even if the topics are violent, difficult.

Among the many objects in your studio, there’s a shop- ping caddy full of things. Where does it come from? The caddy represents the street, poverty, crackheads. People with shopping caddies on the street are often home- less. They salvage whatever they can from the street. It’s a metaphor for my work: to remember those who are forgot- ten, to represent what stinks, what is tough to look at, what is difficult to hear. Also to examine the violence, the misery, the criminals.

“My work expresses the violence we all experience at birth. The pain of coming to life.”

In our previous conversations, you mentioned the con- cept of the urban church when describing your Paris exhibition. What do you mean by that? Etymologically, the word “religion” comes from the Latin reliare, to link things together. A church, beyond any specific religious affiliation, is a place of gathering. A haven of peace. An urban church is a place in the city where one can worship and unburden oneself. It is also a place that I, as an artist, am responsible for decorating and arranging. My parents always told me artists must be rooted in society and in life. They represent a counter force. Whether in Greece or Africa, artists always hold a place in society. I work for the people, not for galleries or institutions

The Paris exhibition is entitled La prochaine fois, le feu (The Fire Next Time), a title that refers to a book by James Baldwin and obviously to the fire that is often present in your practice. Fire, flames, burns. To burn is to destroy, to burn the enemy, to burn values, to burn institutions. But it is also to purify in order for life to appear. It is also something you can’t catch. Fire is volatile. It escapes. It create homes. Once again, somewhere to gather. Human warmth for people. This en- abled the emergence of society. Fire is energy, it activates my works. It is an element that defines me much more than the 60% of water in my body. It breathes life into us. I was especially fascinated by fire during a trip to India where they burn the dead. It is a vehicle to reach an afterlife. The idea of transformation has permeated my work. Even the objects I use are transformed, decomposed…

“My works are always an invitation to make peace, to gather, to talk, even if the topics are violent, difficult.”

I believe you set fire to your Berlin studio too… I grew up in Paris before moving to Berlin. I used to spend my days there on my bike or on foot collecting things. I used to hang out in places where there were only homeless peo- ple. I looked like a bum myself. I was arrested several times, handcuffed. People thought I was on a robbing spree. I had to leave the city. I needed a trigger. So I decided to study at the Academy of Fine Arts in Vienna. The city where I now have a studio. I had to send in a piece for the application, but I wasn’t happy with anything. One day before the dead- line, I bought some planks, big black ones. I was deter- mined. I wanted to create three exceptional pieces. I started to paint everything and I was possessed by an impulse to burn it all. I went into a trance and burnt everything. I nearly set fire to the building. One of the works is called Alexandria, like the library that went up in flames. I wanted something powerful. Something violent. It was as if I’d gone to the underworld and managed to return, but to a crazy new world. I had never achieved such intensity.

And were you accepted at the Vienna Academy? Yes. But I didn’t stay. Academia and institutions are really not my thing.

Find this issue in Numéro art 11, in newsstands and digitally on October 18.